The treatment of pelvic tumors, particularly in the periacetabular region (zone II of the Enneking and Dunham classification), represents a significant challenge for orthopedic oncologic surgeons due to the anatomical complexity and the need to preserve hip function. “Ice-cream cone” prostheses have emerged as a promising reconstructive option due to their versatility and potential to reduce infection rates, although evidence regarding their effectiveness remains limited.

Materials and methodsA retrospective cohort of patients with pelvic bone tumors treated with “ice-cream cone” prostheses between 2016 and 2023 at a single tertiary care center was analyzed. Patients with tumors affecting zone II and undergoing preservation of zone Ia were included. Surgical variables, complications, functionality, recurrence, and mortality were evaluated.

ResultsTen patients met the inclusion criteria. The median age was 50 years, with a mean follow-up of 26.4 months. Chondrosarcoma was the most common tumor (60%). All surgeries achieved negative oncologic margins. The median postoperative score on the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) scale was 22.5 points (range: 12–28). No local recurrence was observed, although one patient developed metastases and another died due to complications of chronic kidney disease.

ConclusionThe use of “ice-cream cone” prostheses for acetabular defects following oncologic resection appears to be a safe and effective technique in selected patients, offering good functional outcomes and high satisfaction, with complication rates comparable to other alternatives.

El tratamiento de tumores pélvicos, particularmente en la región periacetabular (zona ii de Enneking y Dunham), representa un gran desafío para los cirujanos ortopédicos oncológicos debido a la complejidad anatómica y a la necesidad de preservar la función de la cadera. Las prótesis tipo «cono de helado» han surgido como una opción reconstructiva prometedora por su versatilidad y su potencial para minimizar infecciones, aunque la evidencia sobre su efectividad aún es limitada.

Materiales y métodosSe analizó una cohorte retrospectiva de pacientes con tumores óseos pélvicos tratados con prótesis tipo «cono de helado» entre 2016 y 2023 en un único centro de tercer nivel. Se incluyeron aquellos pacientes con afectación tumoral en la zona ii y preservación de zona Ia según la clasificación de Enneking. Se evaluaron variables quirúrgicas, complicaciones, funcionalidad, recurrencia y mortalidad.

ResultadosDiez pacientes cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión. La mediana de edad fue de 50 años, con un seguimiento promedio de 26,4 meses. El condrosarcoma fue el tumor más frecuente (60%). Todas las cirugías lograron márgenes oncológicos negativos. La mediana en la escala Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) postoperatoria fue de 22,5 puntos (rango: 12-28). No se observó recurrencia local, aunque un paciente presentó metástasis y otro falleció por complicaciones de una enfermedad renal crónica.

ConclusiónLa utilización de prótesis tipo «cono de helado» para defectos acetabulares secundarios a resección oncológica parece ser una técnica segura y eficaz en los pacientes seleccionados, ofreciendo buenos resultados funcionales y alta satisfacción, con tasas de complicaciones comparables a otras alternativas.

The treatment of tumours involving the pelvis represents a major challenge for orthopaedic oncology surgeons. The most common primary malignant lesions affecting this region are chondrosarcoma in adults and osteosarcoma and Ewing's sarcoma in paediatric patients.1 In terms of secondary lesions, the pelvis is the second most common site of bone metastasis after the spine, with the most common primary tumours being prostate, breast, kidney, lung, and thyroid cancer.2

In the 1980s, Enneking and Dunham popularised a classification system for the resection of pelvic lesions, dividing the pelvis into four zones. Zone I corresponds to the iliac crest, zone II to the periacetabular region, zone III to the iliac and ischiopubic branches, and zone IV to the sacrum.3 Years later, a subclassification of zone I was added, which is further subdivided into type Ia (those affecting the medial part of the ilium) and type Ib (those confined to the lateral portion of the iliac wing).4 Undoubtedly, zone II is the most complex area from a surgical point of view, as the tumour often distorts the normal anatomy of the region. Furthermore, the oncological objective of achieving clear margins and reducing the risk of local recurrence can be difficult due to the proximity of vital structures and, finally, achieving the greatest possible functionality while compromising the hip joint becomes a major challenge.5–8

Although there are different treatment options, most are associated with a high number of complications or technical difficulties, therefore, there is no gold standard.9–11 Following the introduction of chemotherapy in the 1970s, which increased the survival rate of malignant bone tumours, and technological advances that improved the precision of oncological margins and allowed noble structures to be preserved, limb-sparing surgery gradually replaced radical amputation as the standard treatment.

A booming pelvic reconstructive technique is the use of the ice-cream cone prosthesis, a design that emerged in the United Kingdom in 2003 (Coned Hemi-Pelvis; Stanmore Implants, Elstree).5 It is characterised by its simple placement technique and versatility; it can even be used with little remaining bone and offers the possibility of increasing fixation in a hybrid form using screws together with the placement of a cement mantle with antibiotics, which reduces the risk of one of the most frequent and feared complications of this surgery: infection.12,13

As the literature reviewed on the subject does not provide conclusive scientific evidence, we decided to report our experience of using ice-cream cone prostheses to reconstruct acetabular defects after pelvic tumour resection in zone ii.

Materials and methodsA retrospective cohort study was conducted at a single tertiary care hospital. We used the database recording surgeries in the orthopaedic oncology sector to identify patients and access their electronic medical records, enabling us to collect the variables of interest. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards recognised by the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (CEPI #11635).

We conducted a search from January 2016, when we started to use the ice-cream cone prosthesis design in our centre, to June 2023 for patients diagnosed with a bone tumour in the pelvic region. Patients were included if they had a tumour involving Enneking zone II (periacetabular region) with sparing of zone Ia (the portion of the iliac wing that articulates with the sacrum),4 met the criteria for limb sparing due to no involvement of neurovascular structures, and had the possibility of coverage with or without a flap. Inclusion criteria also included having acetabular reconstruction using an ice-cream cone prosthesis and a minimum follow-up of 6 months.

Demographic information, including histological type and tumour stage, was collected from patients at the time of diagnosis. This information was then studied alongside anteroposterior, outlet and inlet pelvic X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans in order to determine the degree of local invasion. Chest CT and bone or positron emission tomography (PET) scans were used to assess systemic involvement. Image-guided needle biopsy was performed in all cases to obtain the cell strain, which was analysed by a pathologist specialising in musculoskeletal tumours. For oncological staging, we used the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS)14 and the American Joint Committee Cancer15 staging systems. Treatment decisions were made jointly by a multidisciplinary team involving specialists in orthopaedic oncology, clinical oncology, diagnostic imaging, and pathological anatomy.

Patients who were eligible for neoadjuvant chemotherapy received it in accordance with the current international protocols. The treatment was considered successful if 90% or more tumour necrosis was observed by pathological anatomy.16 Preoperative planning was performed with the assistance of 3D navigation, during which we assessed pelvic involvement with a focus on zone IIb involvement. Preservation of zone Ia was an absolute requirement, as this is the minimum pelvic remnant necessary for the fixation of the acetabular component stem. We also assessed femoral involvement, tumour proximity to neurovascular structures, and extension to soft tissues. Intraoperative virtual navigation (IVN) was used to assist with the surgery. IVN merges CT, MRI, and PET images to precisely delineate the tumour, minimising the risk of obtaining tumour-contaminated margins and maximising the preservation of bone and soft tissue. This allows joint reconstruction and closure of the approach.

All surgeries were performed by the same surgical team, consisting of four surgeons with more than ten years’ experience in limb preservation surgery. The aim of the surgery is to resect the biopsy site and remove the tumour en bloc with 2–3cm of surrounding non-tumour tissue, in order to obtain tumour-free microscopic margins, which are analysed using intraoperative freezing. Coxofemoral reconstruction was performed in all cases using an ice-cream cone prosthesis in the acetabular region and with conventional stems or endoprostheses in the femur, depending on the extent of femoral involvement. Initially, the original prosthesis (Coned®; Stanmore Worldwide Ltd, Elmstree, United Kingdom) was used in two cases. However, due to import restrictions and availability issues, similar national designs had to be used (eight custom-made ice-cream cone prostheses, four from Kinetical and four from FICO). This prosthesis is modular, with a rough-surfaced conical stem that allows initial fixation by impaction between the remaining iliac wing plates with subsequent osseointegration. The fixation is complemented with antibiotic cement to reduce the risk of infection and fill the dead space. The cup is hemispherical, with a 20° posterior lip and is attached to the stem via a thread. The stem was placed with the assistance of IVN, with the aim of remaining between the iliac plates and not violating the sacroiliac joint. Femoral reconstruction was then performed, and double-mobility or constrained systems were used to minimise the risk of instability. Once the prosthetic reconstruction was complete, the abductor apparatus was reinserted proximally. Primary closure was achieved in all patients without the need for flaps. We used a continuous suction system on the wound for one week in two patients to minimise the risk of wound complications.

Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered for 24h postoperatively. Drains were typically removed after 48h, and thromboprophylaxis consisted of antithrombotic stockings and a prophylactic dose of enoxaparin for one month. Regarding rehabilitation, passive and active mobility exercises were started on the second postoperative day if pain permitted. From day 5 onwards, walking with partial weight bearing on the operated limb was allowed, protecting the abductor apparatus. Follow-up was clinical and included imaging studies by our multidisciplinary team. Orthopaedic check-ups were weekly until the wound closed, then monthly for the first 6 months, quarterly for the following 2 years, and annually thereafter. Adjuvant treatment and oncological check-ups depended on the tumour type, typically with chest CT scans every 6 months for the first 2 years and then annually.

We collected the following variables: surgical duration, need for transfusion, length of general hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) stay, time to ambulation, and complications during hospitalisation and follow-up, which were reported using the modified Henderson and Clavien-Dindo classification. We also described the management approach in each case.17,18 We assessed the need for any walking aid and used the MSTS scale to assess functionality at the final follow-up.14 This scale comprises six items: pain, function, emotional acceptance, supports, walking ability, and gait. The lowest possible score is 0 and the highest is 30, which indicates complete function. To assess patient satisfaction specifically after undergoing the surgical procedure, we used a visual analogue satisfaction scale (VASS). This consisted of a horizontal line 10cm long and 1cm wide, containing a grey scale ranging from white to black. The dark side corresponded to the highest degree of dissatisfaction (value=0) and the light side to complete satisfaction (value=100). We also reported the proportion of local or distant recurrence of the disease and the mortality rate.

Categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD) or the median and interquartile range (IQR), depending on whether or not they were normally distributed. The distribution of the variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The analysis was performed using Stata v.16 software.

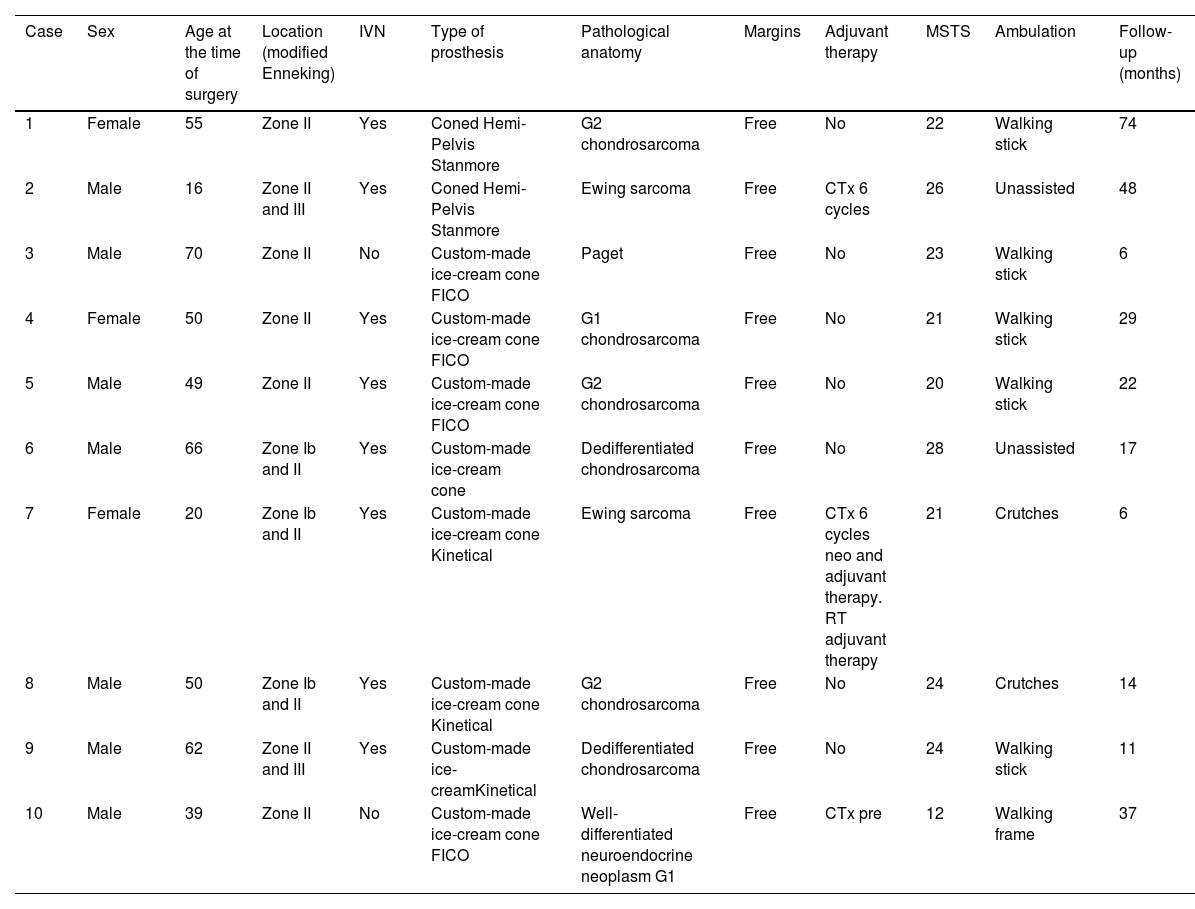

ResultsA total of 151 patients who underwent surgery for pelvic tumours were identified, of whom only 10 (6.6%) met the selection criteria. Eighty per cent (n=8) were male, the median age at the time of surgery was 50 years (IQR: 16–70), and the median follow-up was 26.4 months (IQR: 6–74). Table 1 shows the most relevant demographic characteristics of the patient series (Table 1).

Demographic and surgical variables of the cases in the series.

| Case | Sex | Age at the time of surgery | Location (modified Enneking) | IVN | Type of prosthesis | Pathological anatomy | Margins | Adjuvant therapy | MSTS | Ambulation | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 55 | Zone II | Yes | Coned Hemi-Pelvis Stanmore | G2 chondrosarcoma | Free | No | 22 | Walking stick | 74 |

| 2 | Male | 16 | Zone II and III | Yes | Coned Hemi-Pelvis Stanmore | Ewing sarcoma | Free | CTx 6 cycles | 26 | Unassisted | 48 |

| 3 | Male | 70 | Zone II | No | Custom-made ice-cream cone FICO | Paget | Free | No | 23 | Walking stick | 6 |

| 4 | Female | 50 | Zone II | Yes | Custom-made ice-cream cone FICO | G1 chondrosarcoma | Free | No | 21 | Walking stick | 29 |

| 5 | Male | 49 | Zone II | Yes | Custom-made ice-cream cone FICO | G2 chondrosarcoma | Free | No | 20 | Walking stick | 22 |

| 6 | Male | 66 | Zone Ib and II | Yes | Custom-made ice-cream cone | Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma | Free | No | 28 | Unassisted | 17 |

| 7 | Female | 20 | Zone Ib and II | Yes | Custom-made ice-cream cone Kinetical | Ewing sarcoma | Free | CTx 6 cycles neo and adjuvant therapy. RT adjuvant therapy | 21 | Crutches | 6 |

| 8 | Male | 50 | Zone Ib and II | Yes | Custom-made ice-cream cone Kinetical | G2 chondrosarcoma | Free | No | 24 | Crutches | 14 |

| 9 | Male | 62 | Zone II and III | Yes | Custom-made ice-creamKinetical | Dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma | Free | No | 24 | Walking stick | 11 |

| 10 | Male | 39 | Zone II | No | Custom-made ice-cream cone FICO | Well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasm G1 | Free | CTx pre | 12 | Walking frame | 37 |

CTx: chemotherapy; IVN: intraoperative virtual navigation; MSTS: Musculoskeletal Tumour Society; RT: radiotherapy.

Chondrosarcoma was the most common tumour in 60% (n=6). Five patients had involvement exclusively of zone II, 3 of zones Ib-II, and 2 of zones II-III; the most affected side was the left in 70% (n=7). No patient had metastasis at diagnosis, and two patients had undergone previous surgery. One patient underwent sequential surgery; tumour resection and cement spacer placement were performed in the first stage, and reconstruction with an ice-cream cone-type prosthesis was performed in the second stage. The other patient was a “whoops” case, in which a total hip prosthesis was implanted for suspected avascular bone necrosis, which was diagnosed at another centre, and the pathological anatomy subsequently reported grade 2 chondrosarcoma. The patient required prosthesis removal, margin widening, and replacement of ice-cream cone-type prosthesis. Three patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Table 1).

The mean duration of surgery was 311min. Negative oncological margins were obtained in all cases when analysed by intraoperative frozen section. All patients received blood transfusions, either intraoperatively or postoperatively, with a median of three transfusions (IQR: 1–8). The median hospital stay was 12 days (minimum 7 and maximum 46) and the median stay in the closed unit was 4 days (minimum 0 and maximum 28). The median time from surgery to partial weight-bearing ambulation was 6.5 days (minimum 5 and maximum 33). According to the modified Dindo-Clavien classification18 we had one minor complication: one patient with crural paresis with a strength of 3/5, according to the Medical Research Council scale,19 who at 22 months’ follow-up was able to walk with a cane, and two major complications: one patient who developed intestinal perforation with a fistula to the hip. This required removal of the prosthesis and placement of a cement spacer with antibiotics at 26 months of follow-up. To date the prosthesis has not been reimplanted. Another patient had a dislocation at 7 months of follow-up. This required open reduction and then the acetabular implant failed, with rupture of the stem-cup junction at 12 months. It was therefore revised with another custom-made kinetical ice-cream cone prosthesis.

The median MSTS score was 22.5 points (SD: 4.31) at the end of the follow-up period. All patients except two required a support device for walking. All patients reported being very satisfied with the surgical procedure and its outcome, with a mean VASS score of 8 (SD: 1.8) at the end of the follow-up period. There were no cases of local recurrence of the disease. One patient with dedifferentiated chondrosarcoma was found to have developed brain and lung metastases at the 15-month follow-up. This was treated with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and the patient is currently under the care of clinical oncology. One patient died six months after the procedure due to complications related to chronic kidney disease.

Clinical caseA 55-year-old female smoker presented with left coxalgia that had been progressing for six months. She reported experiencing mechanical pain at night, which did not improve with conservative treatment. Initially, pelvic X-rays were taken, showing a slight alteration to the supra-acetabular trabecular structure in Enneking zone II compared to the contralateral side without cortical involvement (Fig. 1). A CT scan showed a supra-acetabular osteolytic lesion with defined edges and no insufflation or cortical disruption. This lesion appeared to be benign (Fig. 2). An MRI scan was requested but was delayed by five months for bureaucratic reasons. This scan showed a supra-acetabular lesion and the posterior wall and column of the acetabulum. The lesion was hyperintense on the STIR sequence and hypointense on the T1 sequence (Fig. 3). This lesion affected the supra-acetabular region's cortex and caused oedema in the surrounding soft tissues. Bone scan revealed it to be the only hypercaptating lesion (Fig. 4), while the chest CT scan showed non-specific nodules that did not require puncture. Due to the presumptive diagnosis of chondrosarcoma, a biopsy was not performed.

Tumour resection surgery with IVN assistance was decided upon (Fig. 5). Acetabular reconstruction was performed using an ice-cream cone prosthesis and femoral reconstruction with a cemented stem with tripolar constriction (Fig. 6). The anatomical specimen was diagnosed as grade 2 chondrosarcoma with negative oncological margins.

On the left are images of the tumour resection planning using intraoperative virtual navigation; in the centre is the resected surgical specimen and the prosthesis prior to implantation, and on the right are intraoperative images of the cup placement and augmentation of the screw fixation.

Six years after surgery, the patient exhibits a Trendelenburg gait and uses a walking stick; there are no signs of loosening on X-ray. She has had no oncological recurrences (Fig. 6).

DiscussionIn our series, we found that using ice-cream cone prostheses to reconstruct acetabular defects secondary to tumour resection produces good functional results, high patient satisfaction, with complication rates similar to other procedures in short term follow-up.

There are other similar prosthetic alternatives, such as the use of endoprostheses or custom-made prostheses. However, these are technically more challenging and expensive, and are associated with a high risk of infection.20,21 Fujiwara et al., when analysing 122 patients with periacetabular sarcomas treated with limb-sparing surgery (65 custom endoprostheses, 21 with ice-cream cone prostheses, 18 irradiated grafts, and 18 non-skeletal reconstructions), found that in zone II resections with preservation of the iliac wing, reconstruction with ice-cream cone prostheses had the lowest rate of major complications and was associated with the best functional outcomes.9 However, it should be noted that this team developed this design, and therefore outcomes may be subject to selection bias. Similarly, when analysing series similar to our population, as reported by the group of Barrientos-Ruiz et al.,22 in their series of 10 patients, they found comparable results, with an average postoperative MSTS score of 19, with 4 patients developing wound complications, 2 with deep infection. All cases achieved postoperative ambulation with a Trendelenburg gait.

Similar designs to the ice-cream cone prostheses have emerged, including variations of acetabular cups with stems. Zoccali et al. conducted a systematic review of the literature evaluating five implants of this type (McMinn, Schoellner [Zimmer-Biomet], Stanmore, Integra [Lepine], and Lumic [Implant-Cast]), which were used in 428 acetabular reconstructions. They found no differences in complications or postoperative functional outcomes between the different types of prostheses.23

The introduction of IVN has undoubtedly improved the outcomes of this procedure, as demonstrated by Fujiwara et al. in their comparative study. They found that patients in whom navigation assistance were used had a higher percentage of disease-free margins, a lower rate of local recurrence, fewer complications, a better acetabular cup position with fewer implant failures, and better functional outcomes.24

In our series, all the patients were very satisfied with the chosen procedure and the results obtained, despite the complications experienced by some, which were assessed using the VASS. We believe that, faced with a choice between limb amputation or limb-sparing surgery, whenever possible, patients chose the limb-sparing alternative for social, cosmetic, and functional reasons, despite the higher risk of complications. The social and cosmetic impact was not assessed in our study, although previous studies have shown that amputation has a significant negative impact on both the psychological and social wellbeing.25,26

Our study has a number of limitations. It is retrospective, involves a small number of patients, has a short follow-up period, and has no comparison group. While our results are promising, our findings cannot be considered conclusive. We therefore encourage further studies to provide higher-quality evidence.

ConclusionsThe use of ice-cream cone prostheses with IVN for treating acetabular defects secondary to oncological resection could be a safe and effective technique in appropriately selected patients, providing high satisfaction rates, good functional outcomes, and acceptable complication rates.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

Ethical considerationsThis study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards recognised by the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Italian Hospital Italiano of Buenos Aires (CEPI #11635).

FundingNo specific support from public sector agencies, commercial sector, or not-for-profit organisations was received for this research study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.