Pseudoarthrosis and necrosis of the proximal pole of the scaphoid require complex treatment. If primary treatments fail, there are only techniques that sacrifice part of the mobility. We present the design and in vitro results of an anatomical partial prosthesis of the scaphoid bone.

Material and methodThe kinematics of the carpus are tested in vitro on six cadaveric forearms before and after prosthetic replacement, applying active loads on the main muscles. Pre- and post-intervention movements are recorded by Kinescan/IBV®, translating an angular value.

ResultsAfter prostheticization, a decrease in the movement of the capitate (−19.36°) and scaphoid (−15.46°) is recorded during flexion–extension, while that of the lunate increases (11.67°). With the radial-ulnar deviation, only the movement of the great muscle decreases (−11.78°), but that of the scaphoid (4.03°) and lunate (5.9°) increases. We find significant differences whenever there is a decrease in movement. In the “throwing darts” movement (DTM), the average movement decreases in flexion–extension (−18.44°) and in radial-ulnar deviation (−3.66°), without significant differences. While the descent of the scaphoid in flexion–extension and radio-ulnar deviation of the DTM will affect the kinematics (p<.05). There is no involvement of the lunate in the DTM. Regarding the relative interosseous movement, significant differences are observed in the main axis of the F–E.

ConclusionsThe implantation of a stabilized partial scaphoid prosthesis does not significantly modify the movement pattern of a healthy wrist. Therefore, in the future it could be a viable alternative for the treatment of recalcitrant pathology of the carpal scaphoid.

La seudoartrosis y necrosis del polo proximal del escafoides presentan un complejo tratamiento. Si fracasan los tratamientos primarios solo existen técnicas donde se sacrifica parte de la movilidad. Presentamos el diseño y los resultados in vitro de una prótesis parcial anatómica del hueso escafoides.

Material y métodoSobre 6 antebrazos de cadáver se testó in vitro la cinemática del carpo antes y después de la sustitución protésica, aplicando cargas activas sobre los principales músculos. Los movimientos pre y postintervención fueron registrados por Kinescan/IBV®, traduciendo un valor angular.

ResultadosTras la protetización se registró durante la flexo-extensión un descenso del movimiento del grande (−19,36°) y escafoides (−15,46°), mientras que aumentó el del semilunar (11,67°). Con la desviación radial-cubital únicamente disminuyó el movimiento del grande (−11,78°), pero aumentó el del escafoides (4,03°) y semilunar (5,9°). Siempre que existió un descenso del movimiento encontramos diferencias significativas. En el movimiento «lanzar dardos» disminuyó su movimiento medio el grande en la flexo-extensión (−18,44°) y en la desviación radial-cubital (−3,66°), sin diferencias significativas. Mientras que el descenso del escafoides en la flexo-extensión y desviación radio-cubital dentro del movimiento de lanzar dardos sí afectó a la cinemática (p<0,05). No existió afectación del semilunar en dicho movimiento. Respecto al movimiento relativo interóseo, se observaron diferencias significativas en el eje principal de la flexo-extensión.

ConclusionesLa implantación de una prótesis parcial estabilizada de escafoides no modificó de forma significativa el patrón de movimiento de una muñeca sana. Por tanto, en el futuro podría ser una alternativa viable para el tratamiento de la enfermedad recalcitrante del escafoides carpiano.

Due to its complex shape and spatial arrangement, the scaphoid bone transmits between 50% and 80% of the wrist's load. An injury or fracture of the scaphoid-lunate ligament disrupts the balance of different forces, leading to carpal osteoarthritis in 55% of cases.1

Recalcitrant pseudoarthrosis and necrosis of the proximal pole of the scaphoid are difficult-to-treat conditions with an uncertain prognosis, especially in young people. Following a failed graft, the current surgical alternatives available are proximal row carpectomy or carpal arthrodesis. These techniques control pain but considerably reduce joint range of motion, resulting in functional, occupational, and social limitations compared to the healthy hand. A proposed alternative is scaphoid prostheses. For over 60 years, various models made from vitalium, acrylic, silicone, titanium, and pyrolytic carbon have been designed and implanted.2–6 Many of these had very promising short-term results, but were eventually withdrawn due to material-related complications or stability problems.7 There is still no model that allows us to solve these conditions.

The idea behind this study was to provide an alternative treatment for patients with necrosis of the proximal pole of the wrist, recalcitrant pseudoarthrosis where different grafts have failed, carpal bones with SNAC I–II changes, or comminuted scaphoid fractures where primary surgical repair has been impossible. Designing a scaphoid implant would allow us to offer a treatment that controls pain without sacrificing carpal mobility, primarily in young patients. The aim of this study is to test the kinematics of a new stabilised scaphoid prosthetic model in vitro. The implant's uniqueness lies in its ability to restore lost anatomy and maintain carpal height, while also allowing ligamentous connections to be reconstructed.

We hypothesise that the prosthetic implant will reproduce wrist motion while maintaining joint balance, without altering the biomechanics of the bones involved (scaphoid, lunate, and capitate) during flexion–extension (F–E), radial-ulnar deviation (RD–UD), and the dart thrower's motion (DTM). Furthermore, we hypothesise that by reconstructing the scapho-lunate interosseous ligament, the interosseous motion between the scaphoid and lunate bones will not be altered, which will work in unison in all planes of motion.

Material and methodSampleInitially, we calculated the sample size required to compare two means of wrist mobility, pre- and post-surgery. To detect statistically significant differences, we performed a unilateral comparison with a 95% confidence level, 80% statistical power, an accuracy of 6°, and a standard deviation of ±4° for radial deviation and ±3.8° for ulnar deviation. The sample size calculated to achieve these values is five forearms in each group.

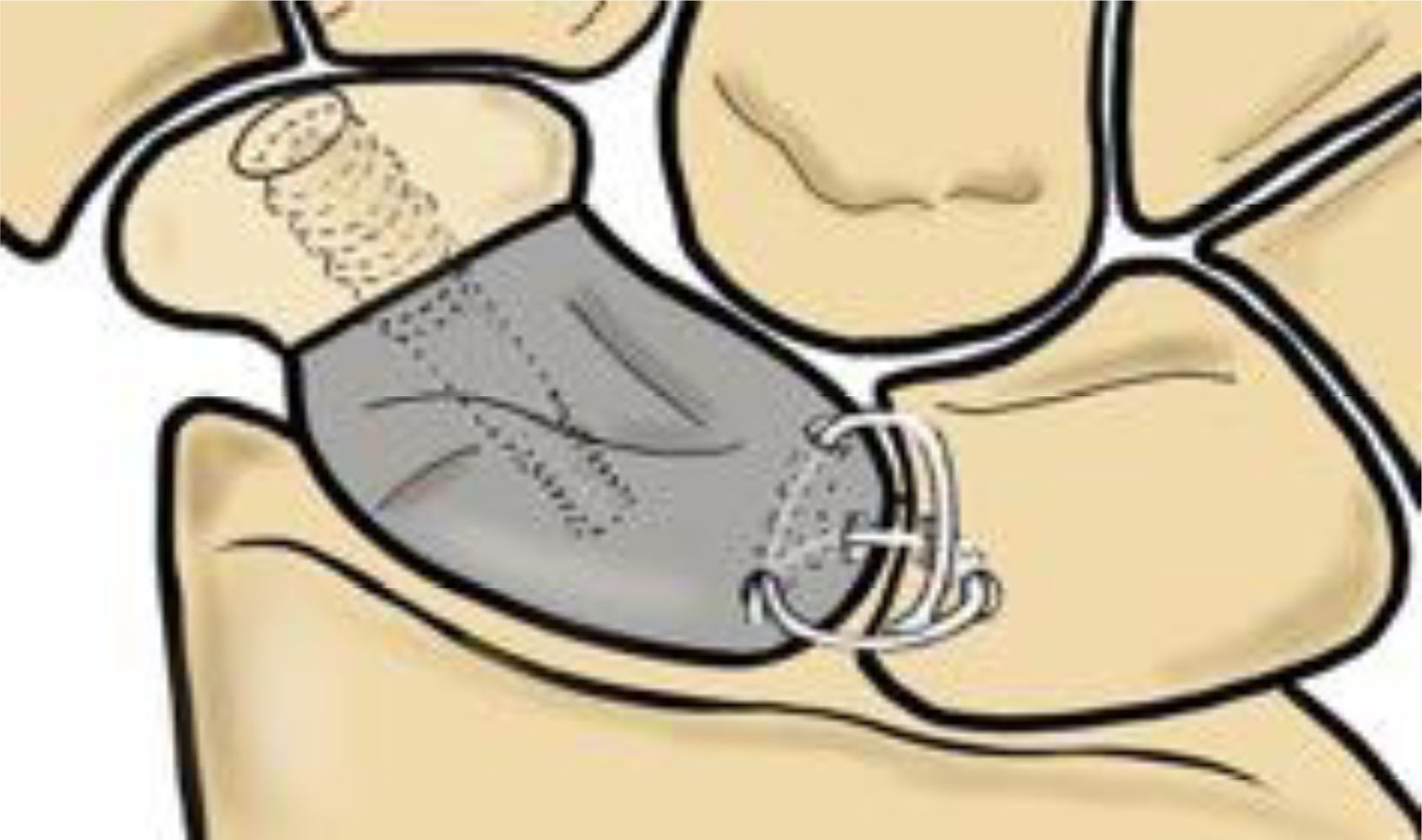

Prosthesis designBased on a computed tomography (CT) scan of the contralateral healthy scaphoid, the measurements and anatomy of the custom-made prosthesis to be manufactured were evaluated, as this has been shown to provide a reproducible mirror image.8 The model's design is fully anatomical, respecting the articular surfaces of the neighbouring bones. It replaces only the proximal 2/3 of the scaphoid, as this is the area with the highest incidence of avascular necrosis (Fig. 1). The prosthesis is manufactured from pure titanium, a biocompatible material, using 3D additive printing technology.

Thanks to Rhinoscero 3D® software, modifications are generated on the CT scan to stabilise the implant to the carpus. At the distal level, the prosthesis must be fixed to the viable scaphoid bone remnant which maintains insertions into the scaphoid–trapezium–trapezoid ligament. To achieve this, the prosthesis has a flat facet perpendicular to its axis, covered with plasma-sprayed titanium, which promotes osseointegration. In addition, this area features a central blind channel for inserting a truncated cone screw, which compresses the distal scaphoid bone and the prosthesis. Meanwhile, three tunnels are created through the implant in the proximal area to allow a ligament plasty to pass through, which is capable of recreating the scapholunate ligament and stabilising the prosthesis to the lunate bone (Fig. 2).

Specimen preparationOur sample consists of six cryopreserved fresh cadaver forearms (four right and two left; age range: 65–87 years), approved for handling by the Ethics Committee (H1494857074740). The forearms have been disarticulated at the elbow and metacarpophalangeal joints. Dissection is then performed in planes, removing all soft tissue except the interosseous membrane, pronator quadratus, carpal ligaments, and the traction tendons where the loads will be applied with their retinacula intact: extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL), extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU), abductor pollicis longus (APL), flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), and flexor carpi radialis (FCR). At the free edge of the five tendons, we perform a Krakow-type suture with synthetic monofilament (PDS® 1) and place a steel washer attached to a load cell. This system uses extensometer gauges to apply loads and translate the manual force applied to each tendon into a measurable electrical signal (Fig. 3).

(3.1) Preparation of the forearms where the main traction tendons are left marked with monofilament sutures for the application of dynamic loads. (3.2) A: Placement of the forearms on a rigid support in neutral pronosupination. B: The image shows the set of markers placed on the scaphoid, lunate, and third metacarpal bone.

The forearms are placed on a rigid support in neutral pronosupination, leaving the wrist free, as proposed by Blankenhorn et al.9

Surgical technique: stabilised scaphoid partial prosthesisFirst, we make a dorsal incision in the third compartment; it is not necessary to retract the extensor pollicis longus, as this has already been removed during anatomical preparation. Next, we perform a transverse dorsal capsulotomy at the radial base, following the dorsal intercarpal ligament, the radiocarpal ligament, and the dorsal edge of the radius. Then, an osteotomy is performed on the scaphoid using a chisel to simulate a non-consolidated fracture enabling the implant created using 3D printing technology to be positioned. In this case, the osteotomy will determine the size of the final implant design. Once the osteotomy has been performed, the proximal third of the scaphoid is removed, after sectioning the ligaments.

Before proceeding with implantation, we prepare the lunate bone to enable proximal stabilisation through ligamentoplasty. First, we carve a central dorsal channel into the lunate bone, extending down to the palmar area and emerging at joint level. We then pass the palmaris longus graft from the palmar to the dorsal side using a thread retriever. Next, we insert the palmar end of the plasty through the volar hole in the prosthesis, exiting dorsally to create a 360° system. The other end of the ligament, located at the dorsal level of the lunate, is then inserted through the dorsal hole in the scaphoid implant and exits through the hole facing the scapholunate joint. Finally, we tighten the ends, checking that the scapholunate space is closed and reduced so that they can be sutured over themselves later. This reproduces the scapholunate ligament in its dorsal and volar parts with additional reinforcement, creating an X-shaped knotted graft that prevents flexion and rotation of the implant (Fig. 1).

For distal stabilisation, a retrograde needle is inserted after placing the wrist in extension and ulnar deviation, following the central hole carved into the implant. This is checked with fluoroscopy, after which the most distal part of the healthy scaphoid is drilled percutaneously and a truncated cone screw, the length of which was previously determined in the CT study, is inserted into the central truncated cone hole. This increases compression between the remaining scaphoid bone and the implant.

Once the ligament has been reconstructed, the capsule is closed and the retinaculum is closed, ensuring that there is no excessive tension.

Protocol and measurement systemIn the measurement protocol, each forearm is evaluated in two sessions: Session 1 (PRE): analysis of the healthy carpus without prosthetic implantation; Session 2 (POST): analysis of the carpus after implantation of the stabilised partial scaphoid prosthesis. During each session, flexion–extension motion, radial deviation/ulnar deviation, and dart thrower's motion are assessed over two 60-second measurements, during which several cycles are recorded. Each complete motion cycle goes from the maximum opposite position, through neutral, to maximum motion.

The motion is always performed manually by the same researcher, who applies loads repeatedly. The Kinescan/IBV® photogrammetry system is used to record the motions. This system uses information recorded by 10 video cameras to obtain spatial coordinates from a set of markers fixed to the forearm, calculating the relative angular motion of the bones analysed, using to the algorithm described by Page et al.10 Each marker system consists of three reflective markers joined together by a rigid support (Fig. 3). These markers are fixed percutaneously and under fluoroscopic guidance to the lunate, scaphoid, and third metacarpal bone axis, enabling the motion of the capitate to be studied.11 Additionally, two isolated markers are placed on the radial and ulnar styloid processes, which are considered to be the neutral position of the wrist with 0° F–E and 0° RD–UD.

Kinematic analysis of active motionDuring the various tests, the rotational motion of the scaphoid, lunate, and capitate is explored in the three spatial axes in relation to the forearm, from the neutral pronation–supination position defined by the International Society of Biomechanics.12 In addition, the overall motion of the wrist is assessed, described as the displacement of the third metacarpal relative to the radius.

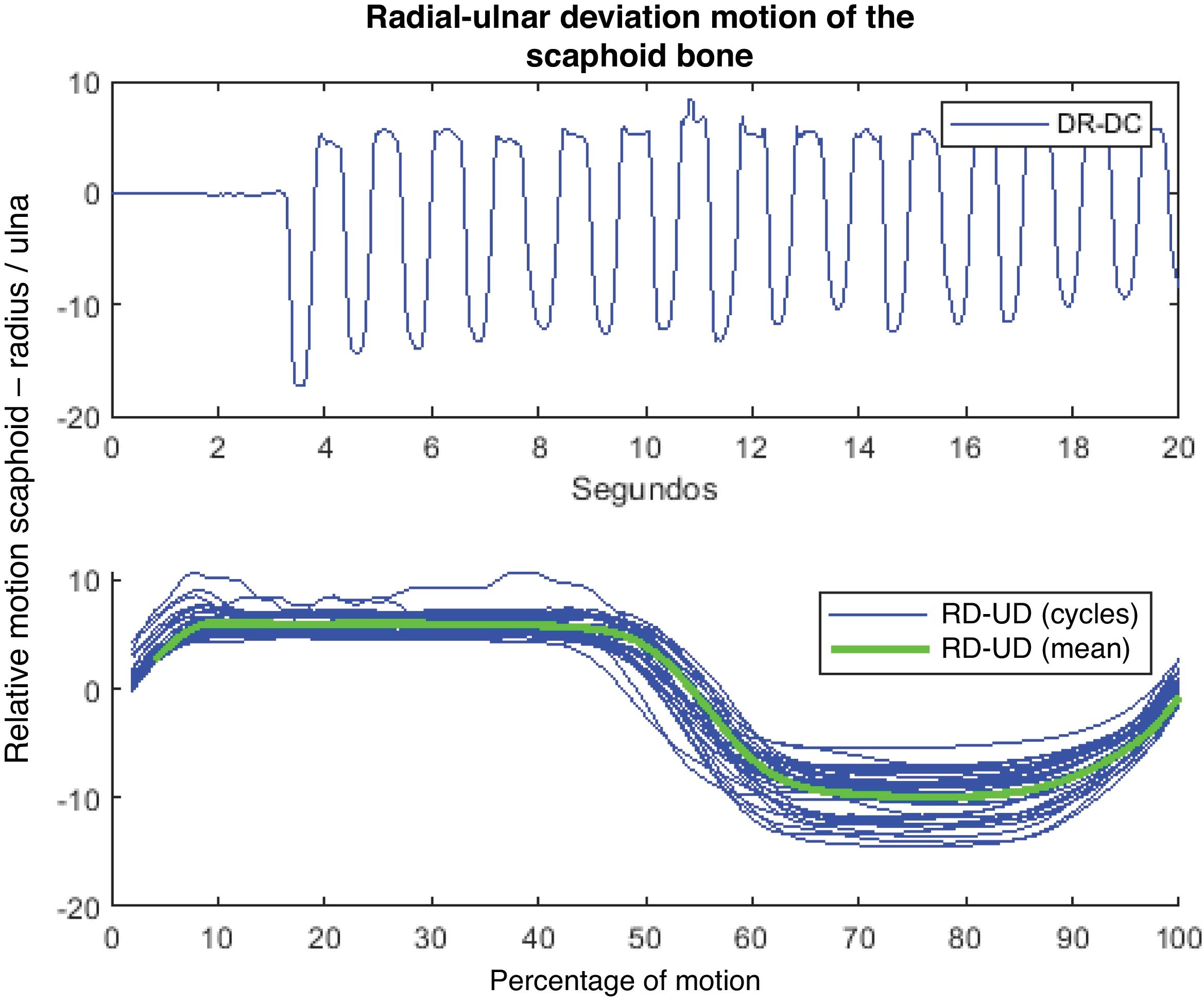

The kinematic data obtained are filtered using a moving average filter with a window length of 100ms.13 For each recorded signal and angle of rotation, the average cycle is calculated (Fig. 4). Prior to this task, each of the cycles was normalised separately in order to obtain signals with the same number of points.

Recording of scaphoid motion with radial and ulnar deviation motions. The upper part shows an example of the type of signal obtained in the scaphoid under radial deviation (RD) and ulnar deviation (UD) motions. This graph shows the variation in angle in degrees throughout the test with a capture frequency of 100 photograms/s. The lower graph shows the average cycle obtained (green curve) from the set of individual cycles performed in the test (superimposed blue curves).

The average motion cycles for each measurement, subject, and session are considered for statistical analysis. Additionally, the maximum and minimum ranges are analysed. First, an exploratory data analysis is carried out, including outlier detection and normality tests (Ryan–Joiner) for each variable. To compare the kinematic behaviour of the cadaveric forearm in all bones before (PRE) and after (POST) implantation, a paired sample T-test is performed. Furthermore, differences in interosseous motion between the scaphoid and lunate bones before and after implantation are analysed using a paired sample T-test. A confidence level of 95% is applied, and therefore a p-value of <.05 is considered statistically significant.

All calculations and statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB 2014a and R software, respectively.

ResultsDescriptive analysis and difference in range of motion in the bones analysedCapitateTable 1 shows the descriptive values of the mean motion of the capitate before and after prosthetic implantation, showing a decrease in the POST session, both in the maximum and minimum ranges and in the mean (Table 1). All the values analysed are within the normal range.

Descriptive results of the capitate, scaphoid, and lunate for the motions analysed.

| Condition | Motion of capitate | Motion of scaphoid | Motion of lunate | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | p-Value | Mean | SD | Min | Max | p-Value | Mean | SD | Min | Max | p-Value | |

| Flexion–extension | ||||||||||||||||

| PRE | 12 | 110.36 | 13.14 | 95.38 | 132.64 | >.06 | 88.86 | 9.23 | 63.28 | 97.57 | <.04 | 48.57 | 11.01 | 32.89 | 64.09 | >05 |

| POST | 11 | 91.64 | 21.1 | 56.48 | 115.43 | >.07 | 72.92 | 16.48 | 47.91 | 98.09 | >.07 | 58.83 | 21.16 | 35.59 | 95.45 | >.07 |

| Radial–ulnar deviation | ||||||||||||||||

| PRE | 10 | 49.27 | 2.87 | 37.48 | 65.74 | >.06 | 16.74 | 3.55 | 3.39 | 37.78 | >.12 | 16.46 | 5.56 | 10.23 | 26.13 | >.15 |

| POST | 9 | 38.49 | 1.59 | 30.26 | 44.89 | >.06 | 20.33 | 2.53 | 11.81 | 32.36 | >.13 | 22.53 | 13.75 | 5.62 | 43.12 | >.23 |

| Dart thrower's motion | ||||||||||||||||

| Flexion–extension | ||||||||||||||||

| PRE | 12 | 95.28 | 20.03 | 52.04 | 127.95 | >.11 | 56.54 | 16.31 | 18.96 | 90.29 | >.05 | 39.28 | 11.07 | 9.85 | 49.63 | <.03 |

| POST | 12 | 76.84 | 13.63 | 59.37 | 102.5 | >.05 | 51.06 | 15.2 | 21.73 | 72.14 | >.09 | 52.33 | 16.15 | 28.8 | 89.73 | >.21 |

| Radial–ulnar deviation | ||||||||||||||||

| PRE | 12 | 43.34 | 9.13 | 29.18 | 54.33 | <.04 | 27.39 | 6.08 | 17.63 | 38.19 | >.07 | 22.44 | 3.93 | 12.81 | 26.73 | >.08 |

| POST | 12 | 39.67 | 10.53 | 24.3 | 58.17 | >.08 | 21.13 | 3.89 | 12.89 | 25.77 | >.09 | 24.63 | 12.33 | 12.06 | 55.23 | >.07 |

N: number of forearm motion cycles used in the analysis.

The mean reduction in motion of the capitate after surgery in the sagittal plane (F–E) is 19.36° (95% CI: 31.18–7.55°) and in the coronal plane (RD–UD) it decreases by 11.78° (95% CI: 20.35°–3.21°), with both differences being significant (p<.05). In the combined dart thrower's motion, we also see that the large bone decreases its range of motion, a mean 18.44° in F–E (95% CI: 37.97°–1.08°) and a mean 3.66° in RD–UD (95% CI: 12.04°–4.71°), but in this case there is no statistically significant difference (Table 2).

Results of the paired sample T-test for differences in POST–PRE implant behaviour in the capitate.

| Capitate motion | N | μd | μd (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion–extension | 11 | −19.36 | (−31.18 −7.55) | .004 |

| Radial–ulnar deviation | 9 | −11.78 | (−20.35 −3.21) | .013 |

| Dart thrower's motion | ||||

| Flexion–extension | 12 | −18.44 | (−37.97–1.08) | .062 |

| Radio-ulnar deviation | 12 | −3.66 | (−12.04–4.71) | .356 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; N: number of forearm motion cycles used in the analysis; μd: mean of the differences between the POST and PRE-surgical sessions. A positive result indicates greater range of motion in the POST-intervention session. A negative result indicates greater pre-implant motion.

Table 1 shows the descriptive values of the scaphoid bone before and after prosthetic implantation, which follow a normal distribution (Table 1).

Compared to a healthy hand, there was a mean reduction of 15.46° in F–E (95% CI: 27.03°–3.09°), 5.48° in F–E of the DTM (95% CI: 21.40°–10.45°) and 6.25° in RD–UD of the same DTM (95% CI: 9.69°–2.82°) after surgery. Only an increase in scaphoid-radial motion (RD–UD) was observed, with an average gain of 4.03° (95% CI: .07°–7.98°) (Table 3). We found significant differences in almost all planes of motion analysed, except in the flexion–extension component of the combined dart thrower's motion. However, as the other component of the motion (RD–UD of the DTM) was altered, we assume that the entire dart thrower's motion was also altered.

Results of the paired sample T-test for differences in POST–PRE implant behaviour in the scaphoid.

| Scaphoid motion | N | μd | μd (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion–extension | 11 | −15.46 | (−27.03 −3.90) | .014 |

| Radio-ulnar deviation | 9 | 4.03 | (.07–7.98) | .047 |

| Dart thrower's motion | ||||

| Flexion–extension | 12 | −5.48 | (−21.40–10.45) | .465 |

| Radio-ulnar deviation | 12 | −6.25 | (−9.69 −2.82) | .002 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; N: number of forearm motion cycles used in the analysis; μd: mean of the differences between the POST and PRE-surgical sessions. A positive result indicates greater range of motion in the POST-intervention session. A negative result indicates greater pre-implant motion.

The descriptive values of the lunate bone reveal that when loads are applied to the tendons, there is greater average motion after the prosthesis is stabilised in the three planes of motion analysed, which is consistent with the hypothesis of normality in all values analysed (p>.05) (Table 1).

When analysing the difference in the average range of motion of the lunate bone between sessions, an increase is observed after the intervention. With F–E, there was an average increase of 11.67° (95% CI: 3.28–26.62°), with RD–UD 5.9° (95% CI: 6.86–18.66°), and with DTM 13.06° in F–E and 2.19° in RD–UD. We found no statistically significant differences when comparing both sessions (Table 4).

Results of the paired sample T-test for differences in POST–PRE implant behaviour in the lunate bone.

| Lunate motion | N | μd | μd (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion–extension | 11 | 11.67 | (−3.28–26.62) | .113 |

| Radial–ulnar deviation | 9 | 5.9 | (−6.86–18.66) | .318 |

| Dart thrower's motion | ||||

| Flexion–extension | 12 | 13.06 | (−3.35–29.46) | .108 |

| Radial–ulnar deviation | 12 | 2.19 | (−5.91–10.29) | .563 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; N: number of forearm motion cycles used in the analysis; μd: mean of the differences between the POST and PRE-surgical sessions. A positive result indicates greater range of motion in the POST-intervention session. A negative result indicates greater pre-implant motion.

We analysed the relative interosseous motion between the lunate and scaphoid that occurs with F–E, RD–UD, and the DTM, evaluating within each the average rotational motion in its three axes (RX: coronal; RY: longitudinal; RZ: sagittal). After placing the implant, we observed a decrease in relative motion between both bones for all components of motion during F–E. However, we only found significant differences in the sagittal (F–E) and longitudinal (pronosupination) motion components, with no alteration in the small interosseous motion of RD–UD (3.17°) (Table 5).

Difference in motion relative to the scaphoid-lunate between the PRE and POST sessions for flexion–extension, deviation, and dart thrower's motions.

| Difference scaphoid-lunate (POST–PRE) | N | μd | μd (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion–extension | ||||

| RX | 11 | −3.17 | (−8.08–1.75) | .182 |

| RZa | 11 | −16.53 | (−26.02 −7.04) | .003 |

| RY | 11 | −4.29 | (−7.98 −.61) | .027 |

| Radial–ulnar deviation | ||||

| RXa | 9 | 3.31 | (−6.91–13.53) | .476 |

| RZ | 9 | −8.47 | (−17.68–.74) | .067 |

| RY | 9 | −.88 | (−4.85–3.09) | .623 |

| DTM: flexion–extension | ||||

| RZa | 12 | −1.06 | (−10.65–8.53) | .812 |

| DTM: RD–UD | ||||

| RXa | 12 | 8.00 | (2.05–13.96) | .013 |

| DTM: rotation | ||||

| RY | 12 | 3.38 | (−.47–7.23) | .080 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; N: number of forearm motion cycles used in the analysis; RX: component of motion in the ulnar–radial deviation access; RY: component of motion in the longitudinal pronation–supination axis; RZ: component of motion in the flexion–extension axis; μd: mean of the differences between the motion of the scaphoid and lunate bones.

A positive result indicates greater range of motion in the POST-intervention session. A negative result indicates greater pre-implant motion.

Next, the difference in relative interosseous motion during RD–UD was evaluated. Greater motion between bones was observed after the intervention in the RD–UD component (3.31°). However, interosseous motion decreased in the other components of motion, decreasing by 8.47° for F–E and .88° for pronation–supination. Despite the results, none reached statistical significance (Table 5).

Finally, we inspected the relative motion between the scaphoid and lunate that occurs with the DTM. After the intervention, there was less relative motion between the two bones when performing the FE of the dart thrower's motion, with no significant differences in this component of the motion (p=.812). When analysing the rotation and RD–UD components within the dart thrower's motion, we found that tendon plasty increases the relative motion between the bones. The increase is 8° with RD–UD and 3.38° with rotation. However, significant differences are only obtained for the radio-ulnar deviation component of the DTM. The rest of the variations do not affect intercarpal motion during the dart thrower's motion (Table 5).

DiscussionIn the last 5 years, thanks to 3D printing technology, new custom-made, full-body scaphoid models made of tantalum have been published, as they have a very similar elasticity modulus to that of bone.8–13 There are recent publications of isolated clinical cases where a custom-made, full-body prosthesis manufactured from the contralateral mirror image in titanium has been implanted, which had a central hole that stabilised it to the lunate bone.14

The fact that so many models have been developed but none have become popular, leads us to believe that there has always been a flaw in either the material, the design (e.g., non-anatomical models or models that do not respect sizing) or the stabilisation of the prosthesis to adapt to kinematics. We therefore consider it necessary to continue working on the design of a suitable implant that takes the complex carpal kinematics into account.

The kinematics of the carpal bones in a healthy hand have been studied both in vitro and in vivo. However, there is still no ideal method. Here, we present the in vitro results of the implant, applying active dynamic loads to the tendons involved in gripping an object, thus improving on other studies that only examine the process passively.15 One of the main advantages of our experimental phase is that there is unanimity, and therefore reproducibility, regarding the definition of neutral pronation–supination and the definition of the neutral starting position, which is recorded digitally using cameras and markers with no possibility of error.12

This study investigates the motion of the capitate, the scaphoid, and the lunate before and after the intervention and positioning of the prosthesis, hypothesising that it is not modified. Like us, Neu and Crisco observe that there is no single plane of motion of the wrist bones, but rather a combined multiplanar rotational motion, where their main motion generally corresponds to the axis being evaluated.16,17

We verified that there is a decrease in the average rotational mobility of the capitate, and therefore of the wrist, in all axes after the operation. Both the average drop with F–E and that of the deviations affect kinematics (p<.05). However, the capitate and carpus remain unaffected during the DTM, maintaining the same kinematic functionality as a healthy hand. This may be because the dart thrower's motion mainly occurs in the midcarpal joint, which is practically unaffected by the prosthesis. Neverthelss, F–E and deviations have a greater component of motion in the radiocarpal joint, which is more altered by prosthetic implantation.

With regard to the overall carpal motion recorded, we obtained ranges close to 110.36±13.14° in the hand without alterations, which decreased to 91.64±21.1° after the prosthesis was implanted. Comparing these results with those of other long-term studies using other non-stabilised scaphoid prostheses reveals wrist F–E ranges between 88° and 101°, which are consistent with our values.18

In the analysis of the rotational motion of the scaphoid, we observe that, after placing the prosthesis, there is a decrease in the average rotational motion with F–E and with the DTM, both with significant differences, while the average rotational motion of the scaphoid in the RD–UD plane increases slightly. This is probably due to the fact that, when stabilising with ligament plasty, flexion–extension is controlled, but not translation in the coronal plane, a component of motion that is probably expressed to a greater degree than thought in the literature. These data contrast with the results obtained by Crisco et al., who conclude that the primary rotational component of the scaphoid with deviations is also flexion and extension, followed by translation and pronation–supination.19 It should be noted that the increase in scaphoid motion with RD–UD is very close to fulfilling the normality hypothesis (p=.0465), so we can assume that the placement of the implant tends to adequately reproduce the motion of the scaphoid with radio-ulnar deviation, although further study is needed to draw conclusions.

Finally, when loads are applied to the lunate bone, greater average motion is observed after the prosthesis has been stabilised in the three planes of motion studied. As with the scaphoid, its main component of motion in all axes of the wrist is flexion–extension accompanied by certain degree of supination and translation.19 The greater rotational motion of the lunate in all planes after placing the prosthesis led us to believe that our scapholunate stabilisation might be insufficient. Nevertheless, the test results show that this is not statistically significant and that, therefore, the placement of the stabilised partial scaphoid prosthesis does not alter its kinematics in any plane of wrist motion.

With regard to scaphoid-lunate interosseous motion, we observe that in our series there is approximately twice as much preoperative mobility of the scaphoid with F–E compared to the preoperative lunate, and that this constant is maintained after implant placement, albeit with a smaller difference. The literature reports data very similar to ours, where scaphoid flexion is always greater than lunate flexion, although to a different degree. Gardner observes that, in a healthy wrist, during flexion, 73% corresponds to the scaphoid, while the lunate contributes only 46%. During extension, the scaphoid participates 99% and the lunate 68%.20 These results, similar to ours, highlight the existence of a difference in intercarpal motion with normal wrist motion. Furthermore, it has been observed that, qualitatively speaking, the lunate follows the scaphoid in its motion if the ligaments are intact and, therefore, moves almost in the same plane of flexion–extension.20–25 Along the same lines, Rainbow observed that when the hand moves from neutral to 60° of flexion, the scaphoid flexes 70% of the amount of flexion of the capitate, while the lunate flexes 45%.1,21,22 With radio-ulnar deviation, the scaphoid and lunate move synchronously but also to different degrees, with individual variations influenced by ligament laxity and the type of lunate.26,27

With regard the dart thrower's motion in a healthy hand, this mainly takes place in the midcarpal region, where the proximal row exhibits variable interosseous motion depending on whether it is studied in vitro or functionally in vivo.28 It has been observed that the scaphoid rotates 26–50% of the total wrist, while the lunate varies from 22 to 40% of the total wrist.29 These variations suggest that there is a wide range of planes; for example, in our study, the scaphoid rotates with high values greater than the lunate, but, according to Leventhal, during a hammering task, the scaphoid rotates 40% and the lunate 60%.30 In our series, after implant placement, greater interosseous motion was observed with rotations and deviation, while it decreased slightly with flexion–extension (−1.06°), with no statistical differences. It should be noted that the deviation component more than doubled, where significant differences were observed. These results lead us to consider a lack of tension in the plasty to control coronal and rotational motions. There are few references to the different components of the dart thrower's motion; however, overall interosseous motion has been studied, concluding that in a healthy hand there is no scapholunate rotational motion during the DTM, as the scapholunate motion decreases and unifies, with the dart thrower's motion symbolising the most physiological axis of motion.20

The sample size is small, which is a limitation of the study. As this is an anatomical study, it has the usual limitations of this type of study: the sample has low variability (all specimens are elderly) and, depending on the preservation and age of the specimen, the limbs may show some anatomical abnormalities. Similarly, the samples have lost their in vivo neuromuscular control, and antagonistic forces were not taken into account during the application of loads, using only gravity. Finally, as this is an in vitro study where the elastic and capsuloligamentous resistance characteristics may be disrupted, we believe it is advisable to subject the implant to a fatigue study under physiological loads to ensure its stability and resistance over long periods of time, as well as the wear it may cause to neighbouring joints, before drawing further conclusions. Another important consideration is that we always conclude that the kinematics are modified with the implant, but in comparison with the control group, which consists of healthy hands without disease. However, the implant is intended for patients with previous carpal conditions, where a degenerative process is developing as a result of pseudoarthrosis or necrosis of the proximal pole, and therefore the results obtained are likely to be more encouraging.

In conclusion, the stabilised partial scaphoid implant harmoniously reproduces the range of motion of a healthy wrist, albeit with less motion in F–E and RD–UD without affecting the dart thrower's motion. We believe that, in the future, it could provide a solution to the problems of recalcitrant scaphoid pseudoarthrosis in patients with high functional demands. Clinical trials are needed to analyse the in vivo integration of the implant and the long-term survival of the plasty.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Ethical responsibilitiesThe study used human forearms, which required approval from the ethics committee: Ethics Committee of the University of Valencia, Faculty of Medicine (H1494857074740).

FundingNo funding was received from a private company to undertake this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.