Tarsal coalitions are aberrant unions of two or more tarsal bones which may condition variable foot and ankle conditions. Their incidence is also variable but most frequently diagnosed coalitions are talocalcaneal and calcaneonavicular. This article aims to evaluate clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients diagnosed with tarsal coalitions.

Materials and methodsCross-sectional descriptive study of patients with tarsal coalitions from August 2007 to January 2020 in a private University Hospital in Madrid, Spain. Data on age, sex, type of coalition according to anatomical location and tissue type, laterality and hindfoot condition and symptoms were obtained and analyzed.

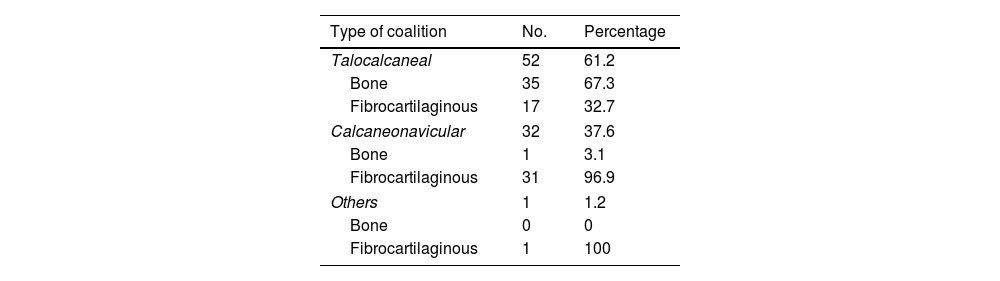

ResultsOf the 57 patients identified (80 feet), there were 31 males (54.4%) and 26 females (45.6%). Average age was 36.9 years. The total number of coalitions was 85. There were 48 bilateral coalitions (56.5%). Fifty-two talocalcaneal coalitions (TCC) (61.2%), 32 calcaneonavicular coalitions (CNC) (37.6%) and 1 calcaneocuboid coalition (1.2%) were registered. Our series showed 36 osseous coalitions (42.4%) and 49 fibrocartilaginous coalitions (57.6%). When evaluated separately, 35 of the TCC were osseous (67.3%) and 17 were fibrocartilaginous (32.7%); 1 of the CNC was osseous (3.1%) and 31 were fibrocartilaginous (96.9%).

DiscussionIn our review, TCC was the most frequent subtype, with the majority being the bony in nature. In the distribution according to sex, a higher incidence of males is found within the CCN group (Fisher's Exact test, p=.032). Some of the results obtained are different from what was previously reported in the literature, which gives rise to new studies that explain this difference in our population.

Las coaliciones tarsianas tienen una incidencia variable, pero se ha reportado que las coaliciones talocalcánea y calcaneonavicular son las diagnosticadas con mayor frecuencia. El objetivo fue evaluar las características clínicas y epidemiológicas de los pacientes con coaliciones tarsianas.

Materiales y métodosEstudio descriptivo transversal de los pacientes con diagnóstico de coaliciones tarsianas desde agosto de 2007 a enero de 2020 en un hospital universitario privado de Madrid, España. Se obtuvieron datos de edad, sexo, tipo de coalición según ubicación anatómica y tipo de tejido, lateralidad, estado del retropié y presencia de síntomas.

ResultadosDe un total de 57 pacientes (80pies), 31 (54,4%) eran varones y 26 (45,6%) mujeres, con una edad media de 36,9años. El total de coaliciones fue 85. El compromiso fue bilateral en 48 coaliciones (56,5%). Se registraron 52 coaliciones talocalcáneas (CTC) (61,2%), 32 coaliciones calcaneonaviculares (CCN) (37,6%) y una coalición calcaneocuboidea (1,2%). Por otra parte, se diagnosticaron 36 coaliciones óseas (42,4%) y 49 coaliciones fibrocartilaginosas (57,6%). Al evaluar en forma separada, 35 de las CTC fueron óseas (67,3%) y 17 fueron fibrocartilaginosas (32,7%); y de las CCN, una fue ósea (3,1%) y 31 fueron fibrocartilaginosas (96,9%).

DiscusiónEn nuestra revisión, la CTC fue la más frecuente, siendo dentro de estas mayoritario el subtipo óseo. En la distribución según sexo se encontró una mayor frecuencia del sexo masculino dentro de las CCN (exacto de Fisher; p=0,032). Algunos de los resultados obtenidos son distintos a lo reportado previamente en la literatura, lo que da pie para nuevos trabajos que expliquen esta diferencia en nuestra población.

The first findings of the existence of tarsal coalitions date back to 3600–2000 B.C.E.1 The incidence reported in clinical studies is 1%–6%,2 but in cadaveric studies using computed axial tomography (CT), an incidence of 12.7% has been recorded, which demonstrates a high level of underdiagnosis.3 Its aetiology can be acquired or, more frequently, congenital, as a result of the failure of the segmentation of the primitive mesenchyme, which normally occurs between the 9th and 10th week of gestation.4–7 Calcaneonavicular coalitions (CNC) ossify between 8 and 12 years of age, and talocalcaneal coalitions (TCC) between 12 and 16 years of age, both being the most frequent variants. They are usually asymptomatic, but may be associated with deformities that cause symptoms, generally after ossification.8–11 In their imaging study, X-rays of both feet should be requested in dorsoplantar and lateral projections, and some specific projections have been described for some coalitions, such as the axial projection of the calcaneus or Harris described for TCC and the oblique projection at 45° for the diagnosis of CNC with a sensitivity of 90%–100% .2,12 Some radiological signs described for CNC are the “anteater sign”, the “reverse anteater sign” and “lateral hypoplasia of the talar head”. For TCC, the “talar beak” and the “C sign” have been described.9,13,6 The latter was reported by Lateur in lateral projections, being described as the line formed by the medial contour of the talar dome and the posteroinferior contour of the sustentaculum tali.14 Years later, Moraleda et al. differentiated four types of “C sign”: complete and incomplete subtypes A, B and C, the first two being the only ones related to the presence of a TCC.15 Due to this variability, CT became more important for diagnosis and currently magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) aims to be the “gold standard” in imaging tests, mainly for its usefulness in the diagnosis of fibrous and cartilaginous coalitions.12,16–21 The aim of our study was to evaluate different clinical and epidemiological characteristics of our patients diagnosed with tarsal coalitions.

Materials and methodA descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in which electronic records and imaging studies performed on patients diagnosed with tarsal coalition at the Quirónsalud University Hospital in Madrid, Spain, were analysed from August 2007 to January 2020. Data were obtained regarding patient age, sex, type of coalition according to anatomical location and type of tissue defined by imaging findings, laterality and status of the hindfoot axis. One patient was excluded if a coalition was suspected clinically and radiologically but who did not attend follow-up with the indicated confirmatory tests. All patients included in the study were diagnosed by members of the foot and ankle orthopaedic unit. The Chi-square statistical test and Fisher's exact test were used to analyse the data.

ResultsAccording to the review of the available clinical information, we can point out that the diagnostic suspicion was made by clinical history, physical examination and simple radiology, with diagnostic confirmation carried out by CT and/or MRI.

The total number of patients diagnosed with tarsal coalition from August 2007 to January 2020 was 57 (80 feet). The distribution by sex was 31 male patients (54.4%) and 26 female patients (45.6%). The mean age at diagnosis was 36.9 years (SD: 18.9), with 12.28% (7 cases) under 15 years of age.

The total number of tarsal coalitions diagnosed was 85, with 100% being located in the hindfoot. Laterality was left in 25 coalitions (29.4%), right in 12 coalitions (14.1%) and bilateral in 48 coalitions (56.5%).

Regarding the type of coalition according to its location, we recorded 52 TCC (61.2%), 32 CNC (37.6%) and one calcaneocuboid coalition (1.2%) (Table 1). Furthermore, regarding the type of coalition according to the origin of the tissue, we obtained 36 cases of bony coalitions (42.4%) and 49 cases of fibrocartilaginous coalitions (57.6%). When evaluating each type of coalition separately, 35 of the TCC were bony (67.3%) (Fig. 1) and 17 were fibrocartilaginous (32.7%); One of the CNC was bony (3.1%) (Fig. 2) and 31 were fibrocartilaginous (96.9%); and the only calcaneocuboid coalition found was fibrocartilaginous (Table 1).

The distribution according to sex for each type of coalition was also evaluated, obtaining that of the TCC 25 were present in men (48.1%) and 27 in women (51.9%), of the CNC 23 were present in men (71.9%) and 9 in women (28.1%) (Table 2). Likewise, of the total of bony coalitions 16 were present in men (48.5%) and 17 in women (51.5%), and of the total of fibrocartilaginous coalitions 32 were present in men (61.5%) and 20 in women (38.5%) (Table 3). Of the total coalitions, 57 (67.1%) were symptomatic and 28 (32.9%) were asymptomatic, being an incidental finding. Of the total symptomatic coalitions (57), 9 cases (17%) had a history of trauma prior to the onset of symptoms. Of the 80 feet that presented a coalition, 75 presented only one (93.8%) and five presented two or more coalitions (6.2%). In the data obtained from the physical examination recorded in the records, of a total of 80 feet, 57 feet presented a valgus hindfoot deformity (71.3%), 8 feet presented a varus hindfoot deformity (10%) and 15 feet presented a hindfoot with a normal axis (18.7%). Of the feet with valgus hindfoot, 66.7% were symptomatic, of those with varus hindfoot, 87.5% were symptomatic, and of those with normal axis hindfoot, 53.3% were symptomatic.

Distribution of coalitions according to anatomical location by sex.

| TCC | CNC | Others | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | ||||

| Number | 25 | 23 | 0 | 48 |

| Percentage | 48.1 | 71.9 | 0 | 56.5 |

| Female | ||||

| Number | 27 | 9 | 1 | 37 |

| Percentage | 51.9 | 28.1 | 100 | 43.5 |

| Total | ||||

| Number | 52 | 32 | 1 | 85 |

| Percentage | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

CNC: calcaneonavicular coalition; TCC: talocalcaneal coalition.

p-Value: .032 Fisher's exact test.

Of the different types of tarsal coalitions described in the literature, there is consensus that the most frequent are CNC and TCC, the sum of both accounting for almost 90% of the total.6 Although the frequency of both coalitions varies in the different published series, there is consensus that CNC would be the most frequent.6 However, in our review, the frequency of TCC was much higher with 61.2% of the total, versus 37.6% for CNC. Stormont et al. in 1984 in a clinical study described a frequency of 53% for CNC.22 On the other hand, Solomon et al. in a cadaveric study of 9 individuals identified 7 CNC (77.7%) and only 2 TCC (22.2%).3 Nalaboff et al., in their study with MRI diagnosis, described that 71.4% of their sample corresponded to CNC.23 In a study of bone remains, Case et al. obtained data from three different archaeological collections, one of European-American individuals, another of South Africans and the third of Danes. Of a total of 1634 skeletons analysed, CNC was the most frequently found in the European-American group (75%).24 Recently, Albee et al., in another study of medieval human bone remains carried out in Exeter, a city in the southwest of England, examined a total of 183 individuals, identifying 8 tarsal coalitions, of which 71% were CNC.25 In this same direction, the latest reviews related to coalitions describe CNC as the most prevalent,2,21,26,27 with few studies describing a slight predominance of TCC10,28 (Fig. 3). Only one study in the literature refers to an incidence similar to that found in our series. Mendeszoon et al. studied the incidence of tarsal coalitions in the Amish population.29 The Amish population is an ethnoreligious, Anabaptist group, known primarily for their simple lifestyle, their resistance to adopting modern comforts and technologies, and for being endogamous. In their study, with 10 years of follow-up, 33 Amish patients were reviewed, and it was found that 29 of the 38 cases (76.3%) had a TCC, while 8 (21%) had a CNC. Only one (2.6%) patient presented a talonavicular coalition.28 The high incidence of coalitions in this group can be explained by their endogamy and the autosomal dominant type of genetic transmission of many tarsal coalitions.

We believe that the result of the predominance of TCC is relevant considering that in our series we have a total number of coalitions greater than other previously published clinical studies and that there was no genetic bias like that in the study in the Amish population. In our series, all coalitions were located in the hindfoot, and there were no cases with midfoot involvement, in agreement with that described by Case et al. in their Danish and European-American groups.24 56.5% of the diagnosed coalitions presented bilateral involvement, which is higher than that described in other studies. Solomon et al. in their cadaveric study reported a 40% incidence of bilaterality and Case et al. in their series described a 43% incidence of bilateral involvement.3,24 Stormont et al., on the other hand, discovered a 22% incidence of bilaterality for TCC and 68% for CNC.22 As authors, we believe that one of the causes of this difference could be the active search for a diagnosis, with contralateral imaging studies in patients diagnosed with tarsal coalition, even if they were asymptomatic.

In the specific analysis according to the type of tissue involved in the coalition, defined by imaging studies, we found a higher frequency of bone TCCs, which also differs from what has been previously published. Rozansky et al. in their series of 35 patients (54 TCCs) studied with CT with three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction described 57.4% of fibrocartilaginous TCCs.30 In the same sense, Nalaboff et al. reported 66.7% and Wang et al., 83.4% of fibrocartilaginous TCCs.23,31 In our review, the CNCs were mostly fibrocartilaginous at 96.9%, which is in agreement with what was described by Upasani et al. who studied 37 patients with suspected coalitions with 3D multiplanar CT, finding 69 CNCs, with only 4% being bone (Fig. 2).32 Recently, in an archaeological study by Albee et al., all the CNCs identified were non-bony.25 The distribution according to sex was slightly higher in men in 54.4% of the cases. This coincides with what has been reported previously, since a distribution without difference by sex is described, with some studies describing a slightly higher prevalence in the male sex.6,22,33 When analysing separately, we obtained a statistically significant relationship between the type of coalition according to anatomical location and sex with a p-value of .032 (Fisher's exact test), with the frequency of males being higher in patients diagnosed with CNC (71.9%).

The total number of asymptomatic coalitions in our case series was 32.9%, a figure similar to the 34.4% reported in the series by Varner et al.28 Regarding the history of trauma prior to the onset of symptoms, it was present in 17% of symptomatic coalitions, which confirms what has already been pointed out in previous studies regarding the fact that minor traumas can trigger or exacerbate the pain of a tarsal coalition.2,10,34 The authors believe that patients with coalitions may become symptomatic when the soft tissue compensation mechanisms that help correct or minimise the effects of the secondary deformity stop working properly. This may explain the different age of presentation of apparently equal coalitions.

Regarding physical examination, the finding of hindfoot valgus was predominant with 71.3%. Although Varner et al. published in their study 22 of 32 cases with neutral hindfoot and only 7 cases (22%) of valgus, there is relative consensus that the most frequent is the flexible or rigid valgus deformity of the hindfoot, with cases of hindfoot in normal axis and with varus deformity being possible but less frequent.2,28,35

Although our series had an adequate total number of cases, and all evaluations and diagnoses were performed by traumatologists specialising in foot and ankle surgery, we would like to highlight the limitation that our study was descriptive and cross-sectional.

From all this analysis we can conclude that we obtained some results that were different from those previously reported in the literature, highlighting the higher frequency of TCC over CNC in our population and also a higher frequency of bone coalitions in the TCC group. This suggests the need for further studies that seek to explain this difference in our population. We also obtained a higher prevalence of bilateral involvement and in the CNC group, the higher frequency in men was statistically significant.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical considerationsThis research was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human or animal experimentation and in accordance with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki, Moreover, we should emphasize that the present research does not include human or animal experimentation.

FundingThis research study did not receive any specific grants from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Our special thanks to Camilo Manríquez Vidal, statistical engineer, for his collaboration in the analysis of results obtained.