Fractures involving the capitellum can be treated surgically by excision of the fragment, or by reduction and internal fixation with screws, with or without heads. The lateral Kocher approach is the most common approach for open reduction. We believe that the limited anterior approach of the elbow, could be a valid technique for treating these fractures, as it does not involve the detachment of any muscle group or ligament, facilitating the recovery process.

Material and methodA description is presented of the surgical technique, as well as of 2 cases with a Bryan–Morrey type 1 fracture (Dubberley type 1A). Two different final quality of life evaluation questionnaires were completed by telephone: the EuroQol Five Dimensions Questionnaire (EQ-5D), and the patient part of the Liverpool Elbow Score (PAQ-LES) questionnaire.

ResultsThe 2 patients showed favourable clinical progress at 36 and 24 months, respectively, with an extension/flexion movement arc of −5°/145° and −10°/145°, as well as a pronosupination of 85°/80° and 90°/90°. The 2 patients showed radiological consolidation with no signs of osteonecrosis. The EQ-5D score was 0.857 and 0.910 (range: 0.36–1), and a PAQ-SLE of 35 and 35 (range: 17–36), respectively.

ConclusionsWe believe that the limited anterior approach of the elbow is a technical option to consider for the open surgical treatment of a capitellum fracture, although further studies are needed to demonstrate its superiority and clinical safety compared to the classical lateral Kocher approach.

Las fracturas que afectan al capitellum pueden ser tratadas quirúrgicamente mediante escisión del fragmento, o mediante reducción y fijación interna con tornillos con o sin cabeza. El abordaje lateral de Kocher es el más usado para la reducción abierta. Creemos que el abordaje anterior limitado del codo podría ser una opción válida para tratar este tipo de fracturas, ya que no implica la desinserción de ningún grupo muscular ni de ningún ligamento y facilita la colocación anteroposterior de los tornillos, que ha demostrado ser biomecánicamente superior.

Material y métodoDescribimos la técnica quirúrgica y evaluamos los resultados en 2 casos clínicos con una fractura de tipo 1 de Bryan y Morrey (tipo 1A de Dubberley) mediante evolución clínica y radiológica. Dos cuestionarios diferentes sobre calidad de vida fueron realizados por teléfono: el EuroQol Five Dimensions Questionnaire (EQ-5D) y la porción contestada por el paciente del Liverpool Elbow Score (PAQ-LES).

ResultadosLos 2 pacientes presentaron una evolución clínica favorable a los 36 y 24 meses, respectivamente con un arco de movimiento de extensión/flexión de −5°/145° y −10°/145°, así como una pronosupinación de 85°/80° y de 90°/90°. Los 2 pacientes presentaron consolidación radiológica sin signos de osteonecrosis, con el EQ-5D de 0,857 y 0,910 (rango: 0,36-1) y el PAQ-LES de 35 y 35 (rango: 17-36), respectivamente.

ConclusionesCreemos que el abordaje anterior limitado del codo es una opción técnica que tener en cuenta en caso de decidirse un tratamiento quirúrgico abierto de una fractura de capitellum, si bien necesitamos de estudios posteriores que demuestren su superioridad y seguridad clínica con respecto al abordaje clásico lateral de Kocher.

Fractures affecting the capitulum can be treated through excision of the fragment (by means of arthroscopy or a Kocher minimal lateral approach) or else through open reduction and internal fixation. These fractures are technically demanding. The Kocher lateral approach is the most commonly employed for the open reduction and internal fixation of fractures affecting the capitulum. It is frequently associated with the de-insertion of the extension and supination musculature in order to increase the exposure of the capitulum and to perform anteroposterior fixation using cannulated or uncannulated screws.1–7 In some cases, it may even be necessary to de-insert the lateral ligament complex from its origin.3,7–9 This approach and its prolongation are not innocuous: the de-insertion of extension and supination musculature and the origin of the collateral lateral ligament require re-insertion (with transosseous sutures or harpoons) and they therefore require extra recovery time because of the morbidity created.1,2 Arthroscopy also has a role to play in the handling of these injuries: it helps when reducing the fracture before finally performing the fixation by means of screws implanted in posteroanterior direction.10–12 We believe that the limited anterior approach of the elbow could be a valid option for the treatment of fractures of this type as it does not imply the de-insertion of any muscle or ligament group, thus facilitating the recovery process. Moreover, the working position is with the elbow extended, which facilitates reduction of the fracture and, in addition, it enables the screws to be implanted in a truly anteroposterior direction as this has been shown to be biomechanically superior.13 We present here the surgical technique proposed along with our experience in 2 clinical cases with over 2 years of follow-up.

Material and methodSurgical technique- 1.

The patient is placed in supine decubitus position on the surgical table, with the arm at 90° abduction and supported on an auxiliary table placed beside the patient. Following the anaesthetic procedure (blocking of the plexus with or without general anaesthesia), we proceed to prepare the surgical field in conditions of asepsis and antisepsis. The ischaemia cuff is on the upper arm and inflated to 250mmHg; an Esmarch bandage is first used to expel blood from the hand, forearm and arm.

- 2.

The surgeon sits beside the patient's axilla while the assistant sits opposite. Space is left to one side of the hand to allow placement of the fluoroscopy equipment.

- 3.

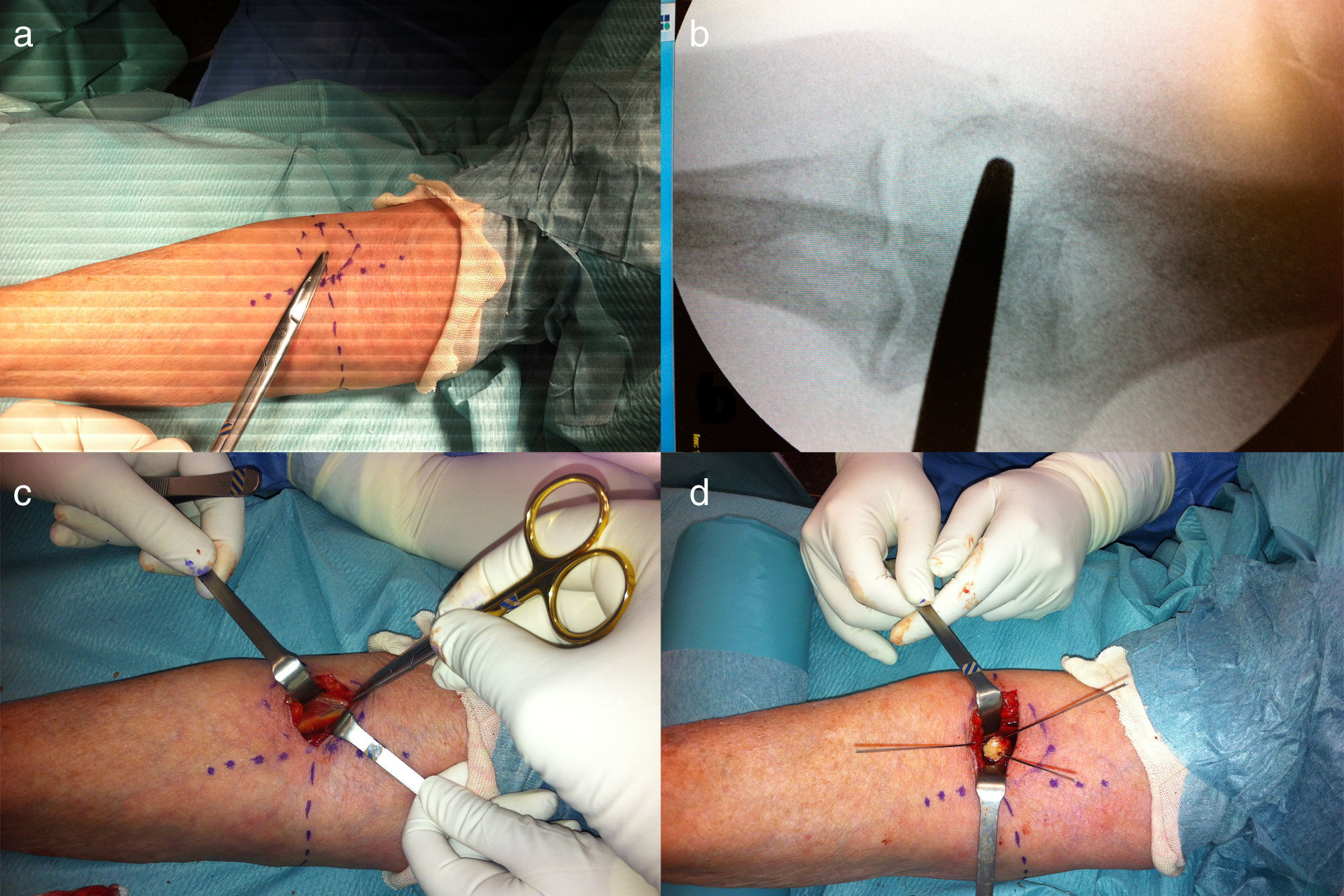

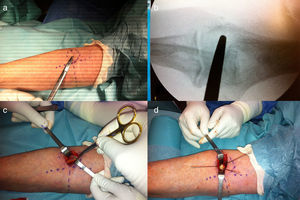

With the elbow at 0° extension, the bicipital tendon is located and a line is drawn on the skin corresponding to a longitudinal axis dividing the fossa of the elbow into two halves. In addition, another line will be drawn to coincide with the fold of the elbow flexion. The lateral end of this transverse line coincides with the diameter of the capitulum in such a way that we can draw a circle running from the intersection of the two lines to the lateral end of the transverse line (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.(a) Drawing in marker pen of the references on the anterior face of the elbow: transverse line at the level of the flexion fold (its external side coincides with the axis transversely crossing the capitulum), longitudinal line centred on the bicipital tendon and, finally, the circular outline of the capitulum. (b) Verification using fluoroscopy of the correct location of the limited anterior approach of the capitulum. (c) After radially rejecting the mobile wad of Henry, we can see how the radial nerve and the recurrent radial artery run protected by the perimysium on the deep face of the brachioradial muscle. (d) After direct reduction of the capitulum fracture, we proceed to its fixation with Kirschner needles.

Note: Fluoroscopy can be used to confirm that the circle drawn corresponds to the anatomical position of the capitulum (Fig. 1b).

- 4.

A small sinuous incision is made transversely with respect to longitudinal axis of the forearm, located just above the circle we have drawn, on its transverse diameter.

Note: The authors prefer to perform this incision in a sinuous shape so as to minimize the effect of any flexion contracture of the scar should it be necessary to extend it either proximally or distally.

- 5.

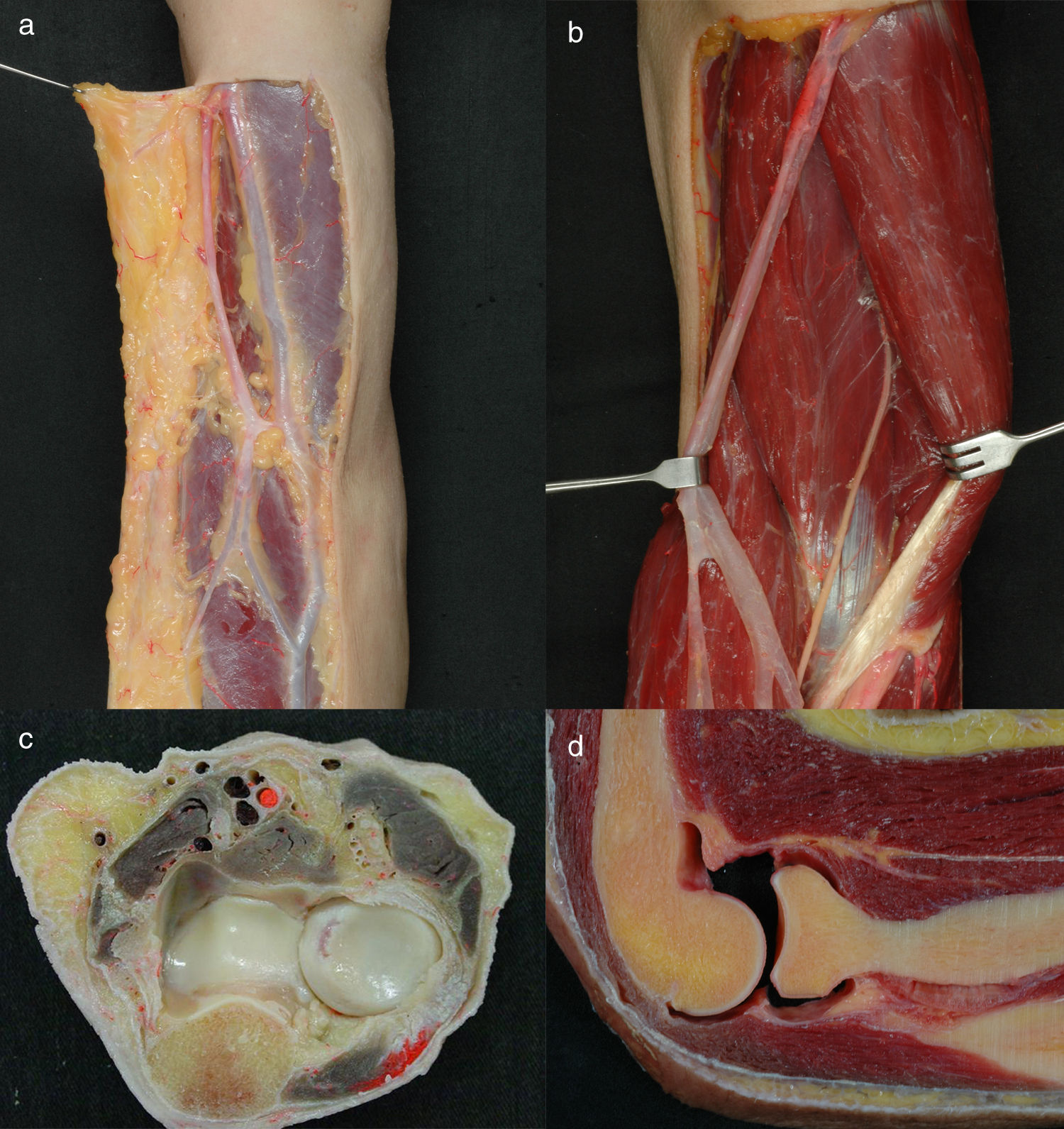

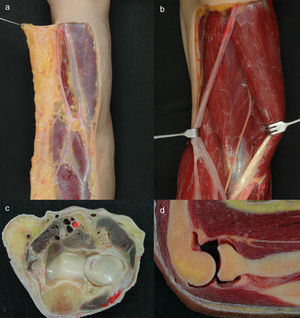

The cephalic vein (Fig. 2a), or one of its branches, is located and a choice must be made, based on its morphology, as to whether to move it aside laterally or medially. Special care must be taken not to impact inappropriately on the superficial fascia as this will be opened in a controlled manner in the next step.

Figure 2.(a) During the dissection of the anterior superficial plane of the elbow, it is possible to observe how the superficial antebrachial veins and, on a lower plane, the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve (musculocutaneous nerve). (b) By ejecting the brachial biceps muscle medially, the musculocutaneous nerve can be seen running between it and the brachial muscle before becoming superficial distally along the radial edge of the brachioradial nerve. (c) Transverse cut of the forearm at the level of the proximal radiocubital joint. (d) Longitudinal view of the elbow, with the entrance of the deep branch of the radial nerve visible between fascicles of the supinator muscle and how close it runs with respect to the joint capsule and the head of the radius.

- 6.

We recommend the dissection of the superficial plane at the superficial fascia level, with the assistance of a gauze supported by our forefinger so as to be able to expose fascial plane perfectly. At this moment, we will be able to identify the medial edge of the brachioradial muscle. The incision will be made longitudinally on the fascia with a scalpel following the internal margin of the brachioradial muscle without penetrating deeply into the plane, only to open the fascia. Next, with the aid of Metzenbaum curved dissection scissors, we will locate the plane between the brachioradial and brachial muscles. A finger moistened with saline solution will help us complete the dissection between the two muscles and locate the radial nerve protected by fatty tissue running underneath the perimysium of the brachioradial muscle (Fig. 2b–d), making its dissection unnecessary as, on the contrary, it remains “protected” in this situation (Fig. 1c). Once the interval (in fact an inter-nerve interval) has been located between the two muscles (the brachioradial and the brachial biceps), we will proceed deeper with the dissection until we palpate the relief of the capitulum in the depth of the dissected plane.

- 7.

We will place 2 Farabeuf retractors (preferably broad bladed), one to retract the mobile wad of Henry (this muscle group will include the radial nerve and the recurrent radial artery) to the lateral side while the other will retract the brachialis muscle and the bicipital tendon to the medial position. It will be possible to see the joint capsule at the bottom of the approach. An incision must be made in the joint capsule (we recommend that a longitudinal incision be used from the proximal humerus to after the outline of the capitulum). At this point, it is necessary to make wither another perpendicular transverse incision on the capsule, or else 2 symmetrical incisions running in opposite directions. The aim is to expose the capitulum without compromising the proximal periosteal pedicle that usually keeps it attached to the distal humerus and provides it with vascularization and stability.

- 8.

Once the joint capsule is open, the capitulum will be exposed and, with the elbow in a 0° extension position, it is usually “reduced” more or less correctly in its anatomical position. Reduction will be performed with attention paid to the distal edge of the distal humerus, a detail that may help is decided on a correct position for the reduction. We will also be able to visualize the relationships of the capitulum fragment with the trochlea at medial level. Once we are sure of the reduction, and with the assistance of 2 or 3 Kirschner needles, we will fix the fragment in place, verifying and measuring the depth of the screw needed by means of fluoroscopy (Fig. 1d).

Note: Extreme care is recommended when placing the Kirschner needles so as not to pierce the distal humerus and insert the needle into the greater sigmoid cavity, as this might cause the needle to break during the verification of the reduction with fluoroscopy (a position requiring the flexion of the elbow to obtain the profile image of the elbow).

- 9.

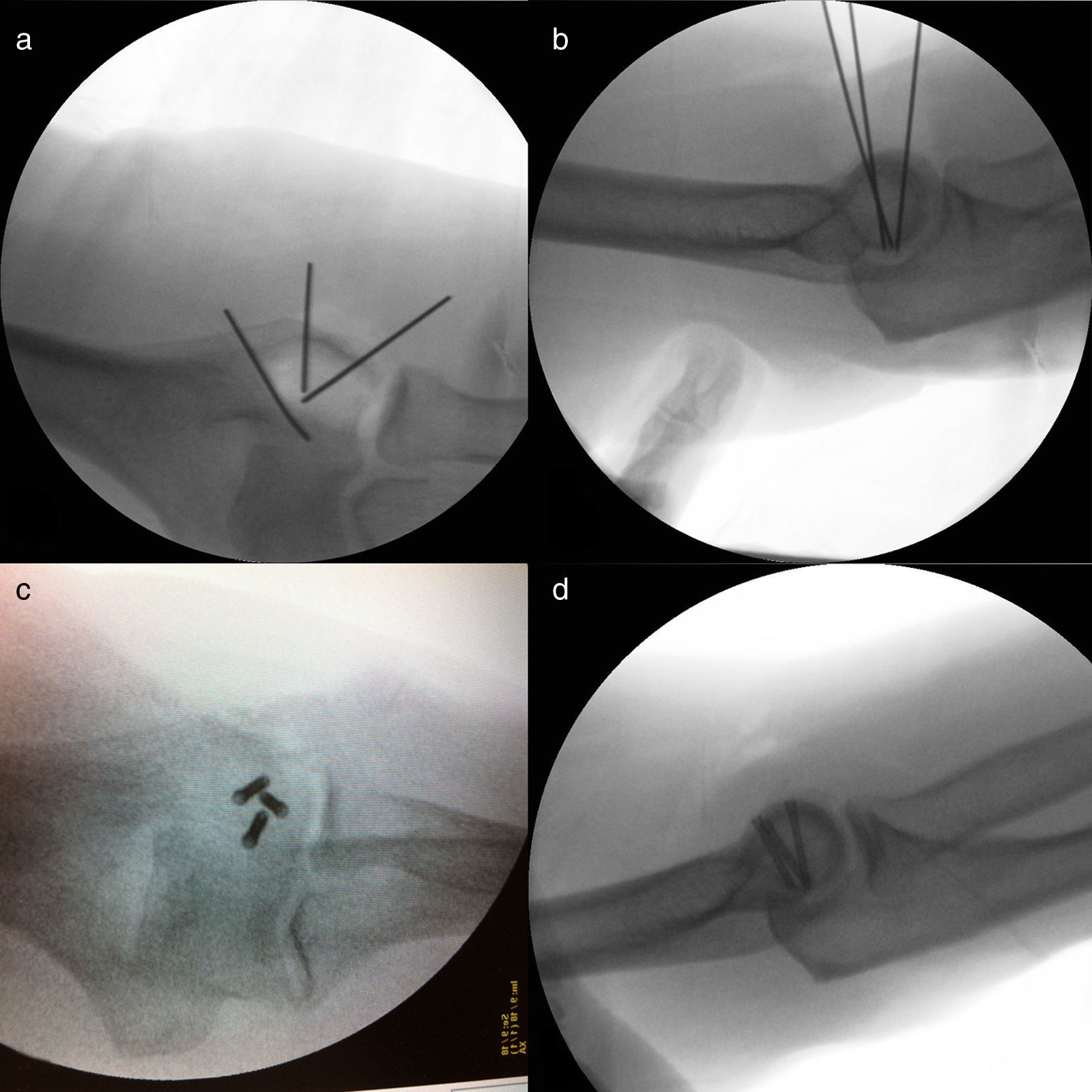

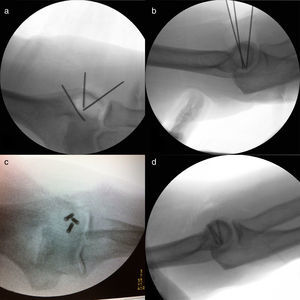

Once the fragment(s) have been reduced, we shall proceed with the measurement and implantation of the headless screws. We shall proceed with the verification of their correct implantation with the fluoroscopy and, in addition, we shall confirm that the elbow has a smooth flexion and extension movement without hitches (Fig. 3a–d). Where the fracture of the capitulum has affected its most distal edge (due to impact or bone loss), we shall see that reducing and stabilizing the fracture will not provide us with a completely smooth surface free from irregularities, and there may, on the contrary, remain some depressions.

Figure 3.(a) Anteroposterior projection of the elbow: verification of the correct placement of the Kirschner needles using fluoroscopy. (b) Lateral projection of the elbow. (c) Lateral projection of the elbow: verification of the correct placement of the cannulated screws using fluoroscopy. (d) Anteroposterior projection of the elbow.

Note: In these cases, we must be particularly careful when mobilizing the elbow after reducing and fixing the fracture, because the head of the radius may impact on and stick at this imperfection so dismantling the fracture. The most dangerous position of the elbow is the same position implied in the mechanism that produced the fracture: falling with the elbow extended so that the extension position between 0 and 30° is the most dangerous in the first few days. For this reason, we recommend that the elbow be kept with a limitation of extension to −45° for 2–3 weeks.

- 10.

The joint capsule will then be sutured, if technically possible, with continuous 4/0 absorbable suture. The subcutaneous level will be sutured with 4/0 absorbable suture and the skin with 4/0 or 5/0 single-filament suture. The elbow will be immobilized at a flexion of 90° for one week to facilitate the correct progression of the soft tissues.

Note: Starting 10 days after the operation, we shall apply an orthopaedic brace to limit elbow extension to −45° and leave elbow flexion and pronation and supination unrestricted. Restriction of extension will be lifted after 3–4 weeks.

We have operated on 2 patients, one a 63-year-old male and the other a 75-year-old female, diagnosed as having a Bryan and Morrey type 11 capitulum fracture (Dubberley type 1A7). The functional and radiological results in both patients after 2 years are described below.

ResultsCase 1Male patient, 63 years old, with a prior history of diabetes mellitus type II, a sleep apnoea syndrome, diaphragmatic hernia, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and ulcerous colitis, who presented at the Emergency Department due to pain and functional impotence in the right elbow following an accidental fall in June, 2013.

During the clinical examination, the right elbow was in a 90° flexion position and he held it in place with his left hand. He presented pain on palpation in the lateral and anterior area of the elbow. No distal motor sensory alteration was present in the limb. He reported that it was impossible for him to move his elbow because the pain.

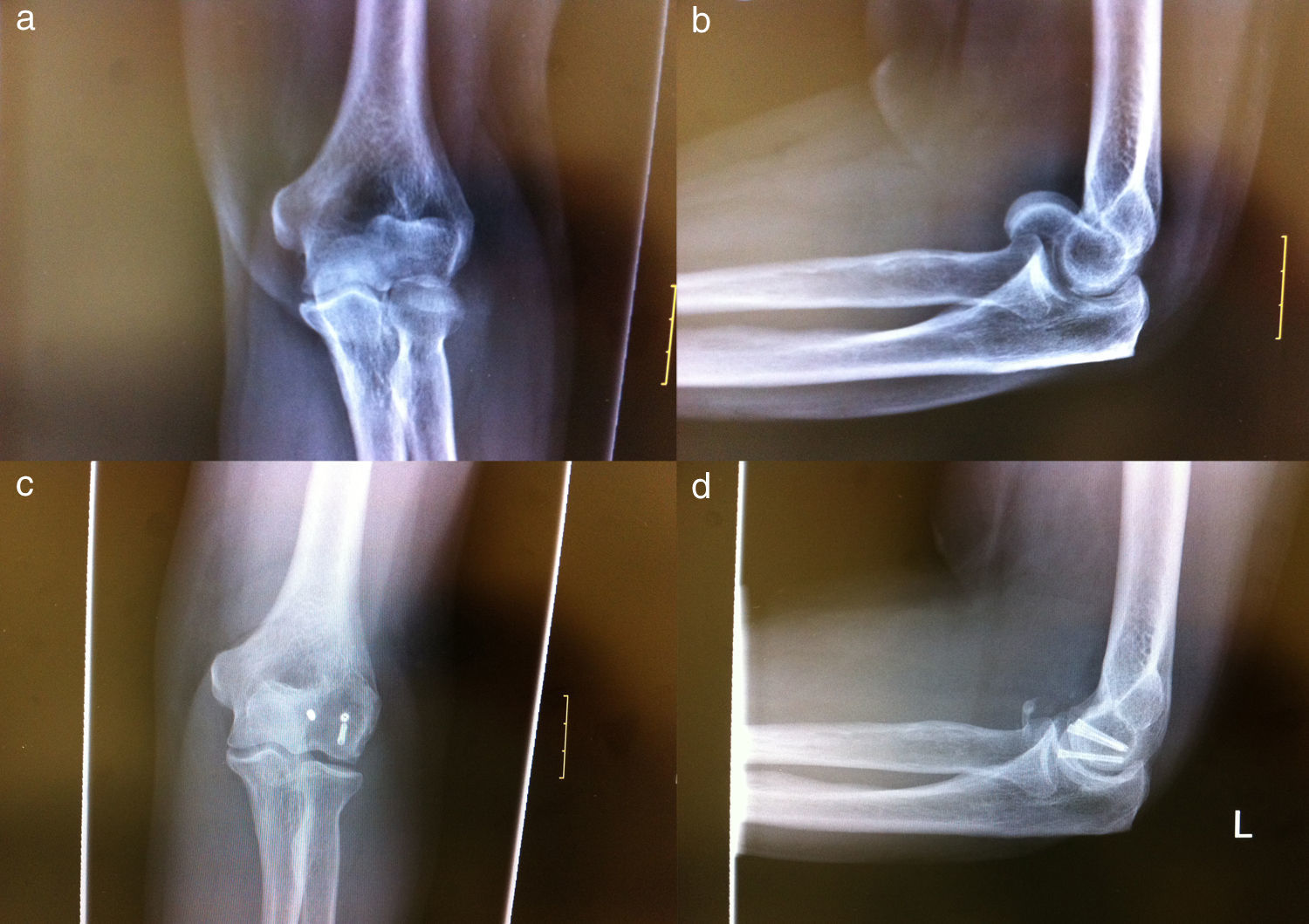

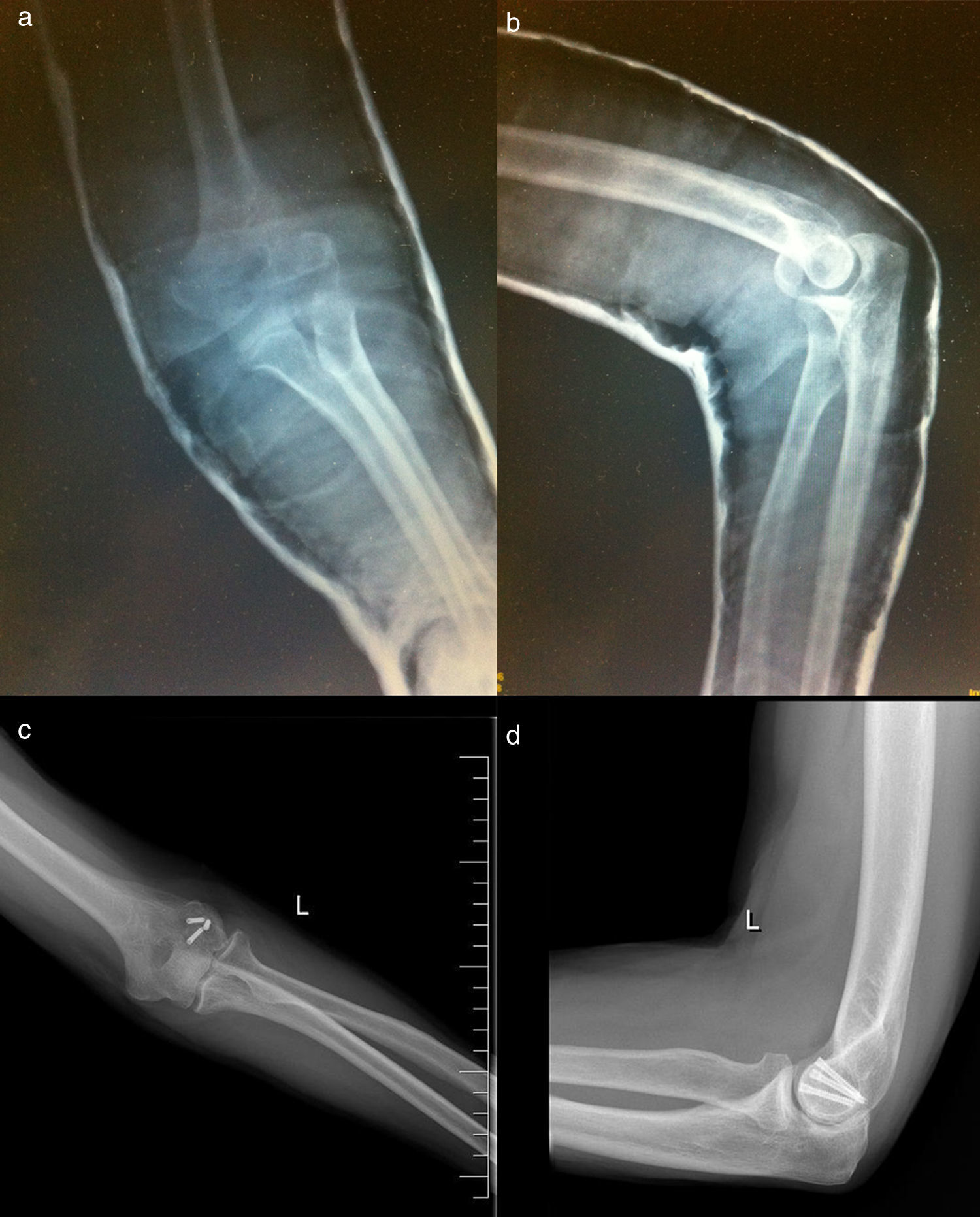

In the radiological studies (anteroposterior and profile X-rays of the elbow and also a CT scan), we observed a displaced capitulum fracture classified as type 1 by Bryan and Morrey (Fig. 4a and b) and Dubberley type 1A. With the plexus blocked, an open reduction and internal fixation was performed using 3 Acutrak Mini headless compression screws (Acumed, Hillsboro, OR, USA) through a limited anterior approach of the elbow.

(Case 1) (a) Anteroposterior radiological projection of the elbow. (b) Radiological projection of the elbow in profile. (c) Anteroposterior radiological projection of the elbow 36 months after surgery. (d) Radiological projection of the elbow in profile 36 months after surgery (it is possible to observe a calcification in the anterior area of the elbow that does not interfere in its functionality).

The elbow was kept immobilized at 90° for 2 weeks by means of an arm and hand ferrule. A fixed articulated brachioantebrachial brace was then applied with unrestricted flexion of the elbow, unrestricted pronation and supination and extension limited to −45°. Rehabilitation was begun and the patient was instructed to perform flexion and extension exercises with resistance every 2–3h. Four weeks after the operation, elbow flexion and extension was left unrestricted.

Six months after the operation, the patient presented an elbow extension of −5°, flexion of 140° and pronation and supination of 80°/80°. The follow-up X-rays showed consolidation of the fracture, without any appreciation of secondary displacement. After 36 months following surgery, the range of mobility was: extension −5°, flexion 145° and pronation and supination 85°/80°, while the radiographic study did not reveal any necrosis of the capitulum, nor secondary displacement (Fig. 4c and d). The aesthetic sequelae are minimal. The EuroQol Five Dimensions Questionnaire (EQ-5D) gave a score of 0.57 (range: 0.36–1) and the Liverpool Elbow Score (PAQ-LES) was 35 (range: 17–36). According to both these scales, the most frequent symptom was pain, which was mild and occasional. The patient did not report any difficulties with activities of daily living or domestic tasks (combing his hair, showering, eating, dressing, shopping).

Case 2Female patient aged 75 with a history of arterial hypertension and dyslipidaemia who attended the Emergency Department after suffering an accidental fall at home. She reported pain and functional impotence in her left elbow in March 2014.

During the clinical examination, she presented some difficulty in extending the elbow with crepitus on pronation and supination. She did not present any distal sensory or motor deficit in her left arm. The X-rays of her elbow revealed a Bryan and Morrey type 1 displaced left capitulum fracture (Fig. 5a and b). The CT study described an intra-articular comminute fracture of the humeral condyle with displaced fragments, causing articular incongruency and haemarthrosis in the elbow (Dubberley type 1A).

Internal fixation was achieved using 3 Acutrak Mini headless compression screws (Acumed, Hillsboro, OR, USA) through a limited anterior approach of the elbow.

The elbow was kept immobilized at 90° for 2 weeks by means of an arm and hand ferrule. An articulated brachioantebrachial brace was then applied with unrestricted flexion of the elbow, unrestricted pronation and supination and extension limited to −45°. Rehabilitation was begun and the patient was instructed to perform flexion and extension exercises with resistance every 2–3h. Four weeks after the operation, elbow flexion and extension was left unrestricted.

Six months after the operation, the patient presented an elbow extension of −20°, flexion of 145° and pronation and supination of 85°/80°. The follow-up X-rays showed consolidation of the fracture, without any appreciation of secondary displacement. After 26 months following surgery, the range of mobility was: extension −10°, flexion 145° and pronation and supination 90°/90°, while the radiographic study did not reveal any necrosis of the capitulum, nor secondary displacement (Fig. 5c and d). The EQ-5D score was 0.910 (range: 0.36–1) and the PAQ-LES was 35 (range: 17–36). According to both these scales, the most frequent symptom was pain, which was mild and occasional. The patient did not report any interference from this minor discomfort with activities of daily living or domestic tasks.

DiscussionAnterior approaches of the elbow, although not frequently employed, have been described and used by many surgeons. According to Henry, the anterior approach of the elbow has been used for the synthesis of proximal fractures of the radius, for the re-insertion of the distal tendon of the biceps, for the exaeresis of anterior tumours of the elbow and for debriding in the event of soft tissue infections. Nonetheless, in view of the anatomical characteristics of the area and because the elbow can be approached from other directions with fewer neurovascular structures, the fact is that the anterior approach of the elbow is not frequently used.1,2,7–9,14

When accessing the capitulum from an anterior approach and seeking the interval between the brachioradial muscle and the brachial biceps, we shall leave the radial nerve (that might already be divided into its deep and superficial branches) included on the aponeurosis of the brachioradial muscle, so its dissection is unnecessary.8–10,14 We believe that this is a strength of this approach for its dissemination and for highlighting its safety, as it involves minimal manipulation of the radial nerve and the recurrent radial arteriovenous package.

The other interesting point for discussion has to do with the reduction and survival of the fragment of capitulum, normally found attached to the distal humerus by a proximal periosteal flap acting like a hinge and enabling the bone fragment to be displaced upwards and proximally as if it were a “door”. This capitulum fragment is intra-articular at its distal end, is covered in cartilage and does not have any connections, therefore part of its survival will depend on the conservation of the proximal periosteum. The other point is that reduction of the fracture with the elbow flexed is difficult as the head of the radius is in the way and hinders the natural closure movement of the “capitular door”, thus occasionally forcing the proximal periosteum to be de-inserted.

The Kocher approach is the one most commonly used in the procedure for open reduction and internal fixation of a capitulum fracture. Some authors add an additional posterior approach for the implantation of the screw in posteroanterior direction, although fixation in anteroposterior direction13 is known to be biomechanically more stable. Nonetheless, some authors have claimed that posteroanterior placement of the screw reduces the damage to the articular surface caused by anteroposterior fixation. Various biomechanical studies have shown the superiority of headless screws compared to the use of Kirschner needles and cancellous bone screws. Other authors have performed reduction and internal fixation by means of arthroscopy.11,12,15 In these cases, the arthroscopic vision of the anterior part of the elbow helps in the fracture's reduction, although, in the cases described in the scientific literature, the osteosynthesis screws were implanted in posteroanterior direction, and arthroscopic reduction is not always possible, sometimes requiring the performance of a complementary lateral Kocher approach. In a paper on the arthroscopic treatment of capitulum fractures, Kuriyama mentions that one of the 2 cases described required reconversion to open reduction through a Kocher approach due to difficulties in the reduction.12

Whenever a Kocher approach is used, the natural working position is with the elbow flexed at 90° as this relaxes the muscle structures and the joint capsule, and it is easier to separate them to access the joint. This position of the elbow, however, is not the most suitable for the reduction of a capitulum fragment: the most suitable position is to keep the head of the radius away from the distal humerus and this is achieved with an elbow extension of 0°.

Fractures of the capitulum often do not affect only the capitulum but also include a fragment of trochlea.1,3,5,7 This situation may require the implantation of a screw on the more lateral side of the capitulum. When the option chosen has been to access using the Kocher approach, we know that the most lateral part of the capitulum is easily accessible but, if we need an even more medial access, it is very possible that we will have to enlarge the initial approach. This enlargement of the approach includes the de-insertion of the extension and supination musculature and the radial ligament complex from their origins. Even enlarging the approach, however, when it comes to the temporary fixation of the fragment using Kirschner needles to serve as guides for the implantation of the definitive cannulated screws, we realize that the placement direction will not be perfectly perpendicular to the plane of the fracture. By approaching from the lateral side, the work area forces us to implant the screws at a slight angle (around 30–45°) in lateromedial direction, a situation that can be easily verified in any anteroposterior radiographic projection found in the literature, where the screws can be observed in almost total extension, as if they were “lying flat”. All these technical steps will require, at the conclusion of the reduction and fixation of the fracture, a correct re-insertion, which in turn will impact on post-operative protocol as it will be necessary to protect not only the fracture but also the re-inserted muscles and ligaments. The use of the enlarged anterior approach has recently been published for the reduction and fixation of a Bryan and Morrey type 4 fracture of the distal end of the humerus in a 16-year-old patient with a favourable clinical outcome and without neurovascular complications.16

Our preferred osteosynthesis technique is fixation by means of headless cannulated screws. The use of cannulated screws guided by Kirschner needles may help to confirm its correct position and so prevent the possibility of repeated attempts at drilling in the case of poor positioning of the bit when using non-cannulated screws. Whenever we perform an anterior approach, the placement of the Kirschner guide needles and the definitive implants is done in a plane truly perpendicular to the plane of the fracture. This situation has been shown to be ideal from a biomechanical perspective.13

Finally, we should mention that our 2 cases have presented a satisfactory evolution from a clinical standpoint (in both functional and aesthetic terms) and also from the radiological and quality of life perspectives, more than 2 years after the surgical procedure. Both patients presented a favourable clinical evolution after 36 and 24 months, with an extension/flexion movement arc of −5°/145° and −10°/145°; as well as pronation and supination of 85°/80° and 90°/90°, respectively. Radiologically, both patients presented consolidation without signs of osteonecrosis, with EQ-5D scores of 0.857 and 0.910 (range: 0.36–1) and PAQ-LES scores of 35 and 35 (range: 17–36), respectively. This functional outcome is similar to the results published in Dubberley's paper7: in his series of 28 patients, the final mean extension was −19±15°, although it is true that the mean extension of the group of patients specifically with a Dubberley type 1A fracture was 10° (in our 2 cases the mean extension was −7.5°).

ConclusionsThrough this article, we wish to disseminate the usefulness of the limited anterior approach of the elbow as another option to bear in mind for the surgical treatment of Bryan and Morrey type 1 (Dubberley type 1A) capitulum fractures of the elbow. This is not an area in which we habitually work but it is accessible and, with a careful dissection technique, we can minimize the possibility of damaging the radial nerve. Technically, we believe it has advantages in terms of accessibility, the correct reduction of the fracture, the placement of the implants and post-operative recovery, as well as disadvantages with respect to the need for a careful surgical technique. Nonetheless, we are aware that the data presented here are insufficient, in view of the small number of cases reported, to be able to affirm that this is a demonstrably superior approach. In our opinion, it will be necessary to analyze further cases treated in a similar way and to conduct comparative studies between the technique proposed and the classical Kocher approach. Furthermore, we shall need to report, for example, on the handling of Bryan and Morrey type 4 fractures in order to conclude that it can be used in all capitulum fractures. Even so, we believe that our initial experience might open the door for consideration of the limited anterior approach of the elbow for limited access in the handling of capitulum fractures.

Level of evidenceLevel IV evidence.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors state that no experimentation on human beings or animals has been conducted for the purposes of this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors state that this article contains no patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors state that this article contains no patient data.

Conflict of interestThe authors have not received any financial assistance whatsoever for the execution of this paper. Nor have we signed any agreement whereby we will receive any fees or benefits from any commercial entity. No commercial entity has paid, nor will pay, any foundations, educational institutions or other not-for-profit organizations to which we are affiliated.

Please cite this article as: Ballesteros-Betancourt JR, Fernández-Valencia JA, García-Tarriño R, Domingo-Trepat A, Sastre-Solsona S, Combalia-Aleu A, et al. Abordaje anterior limitado del codo para la reducción abierta y fijación interna de las fracturas del capitellum. Técnica quirúrgica y experiencia clínica en 2 casos con más de 2 años de seguimiento. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:176–184.