The opinions of 21 experts in knee surgery were evaluated in this study, using a DELPHI questionnaire method in two successive rounds, on 64 controversial scenarios that covered both the diagnosis and possible treatment of painful knee replacements. The level of consensus was significantly unanimous in 42 items and of the design in 5, with no agreement in 17 of the questions presented. In light of the published scientific evidence, the surgeons who took part showed to have a notable level of information on the most effective diagnostic tests, although, it should be pointed out that there was a lack of confidence in the possibility of ruling out an infection when the erythrocyte sedimentation rate and the C-reactive protein were within normal values, which have been demonstrated in the literature to have a high negative predictive value.

As regards the treatments to employ in the different situations, the responses of the expert panel were mainly in agreement with the data in the literature.

The conclusions of this consensus may help other surgeons when they are faced with a painful knee prosthesis.

En este estudio se valoran las opiniones de 21 expertos en cirugía de rodilla, mediante la metodología Delphi de cuestionarios en 2 rondas sucesivas, sobre 64 escenarios controvertidos que abarcan tanto el diagnóstico como el posible tratamiento de las artroplastias de rodilla dolorosas. El grado de consenso fue significativamente unánime en 42 ítems y el de disenso en 5, sin encontrar acuerdo en 17 de las cuestiones planteadas. A la luz de la evidencia científica publicada, los cirujanos que participaron demostraron un grado notable de información sobre las pruebas diagnósticas más rentables, aunque llama la atención la falta de confianza en la posibilidad de descartar una infección cuando la velocidad de sedimentación y la proteína C tienen valores normales, lo que ha demostrado en la literatura tener un alto valor predictivo negativo.

Respecto a los tratamientos a emplear en las distintas situaciones, las respuestas del panel de expertos estuvieron mayoritariamente en consonancia con los datos de la bibliografía.

Las conclusiones de este consenso pueden ayudar a otros cirujanos en el momento de enfrentarse a una prótesis de rodilla dolorosa.

In the last 25 years, joint replacement (or arthroplasty) techniques at the level of the knee have been very successful. The number of implants in the USA doubled between 1999 and 2008, when 600,000 total knee arthroplasties were implanted.1 In Spain, the estimated number of knee prostheses is around 45,000, although there are no official figures. The increase of indications, the seventh decade of life of the baby boom generation and the extension of this technique to an increasingly younger population lead us to expect an even greater increase during the next decade, not only of primary implants, but also of rescue procedures due to complications.2

Failures represent only a small amount, no more than 10% of implants at 10–15 years, but their consequences are devastating. The predominant causes are infection of the prosthesis, instability and aseptic loosening.3

Considering the current controversy surrounding rescue of failed implants and the need to optimize resources, it is important that surgeons facing painful knee replacements are able to recognize failure patterns and apply treatments in a systematic manner. The objective of this work was to obtain the opinion of experts on this subject through a structured, remote technique, in order to reach a consensus including professional criteria and evidence-based clinical recommendations. This will help in the decision-making process and reduce variability in clinical practice regarding this controversial issue.

MethodologyWe used a widely employed technique in biomedicine to obtain a professional consensus among a group of experts who were not physically present (modified Delphi method).

This method consists of 2 rounds of e-mailed questionnaires. The results of the first round were processed and published so as to allow reconsideration of manifestly diverging positions prior to starting the second round with the non-consensus items.This survey technique is reliable and has a long standing tradition in biomedical research.4–7

Some important advantages of this consensus method are:

- •

It preserves anonymity, thus defending individual opinions.

- •

It allows a controlled interaction of each member with the views of the rest of the group.

- •

It provides the opportunity for each participant to reflect and reconsider opinions between the first and second round.

- •

It offers the possibility of changing stances, if the arguments presented justify it, without this being known to the other panelists.

- •

There is statistical validation of the consensus achieved.

The first 3 authors of the work constituted the Scientific Committee which chose 3 problematic aspects of painful knee prostheses:

- •

Diagnosis of prosthesis infection.

- •

Diagnosis of instability.

- •

Initial therapeutic attitude in cases of infection/instability.

This committee developed a set of 64 professional criteria or proposals (items) related to the aspects mentioned, which reflected professional judgment on the subject under study and which were submitted for the consideration of a group of 21 specialists, with a special interest in knee pathology, and whose usual clinical practice included a significant number of implanted knee arthroplasties.

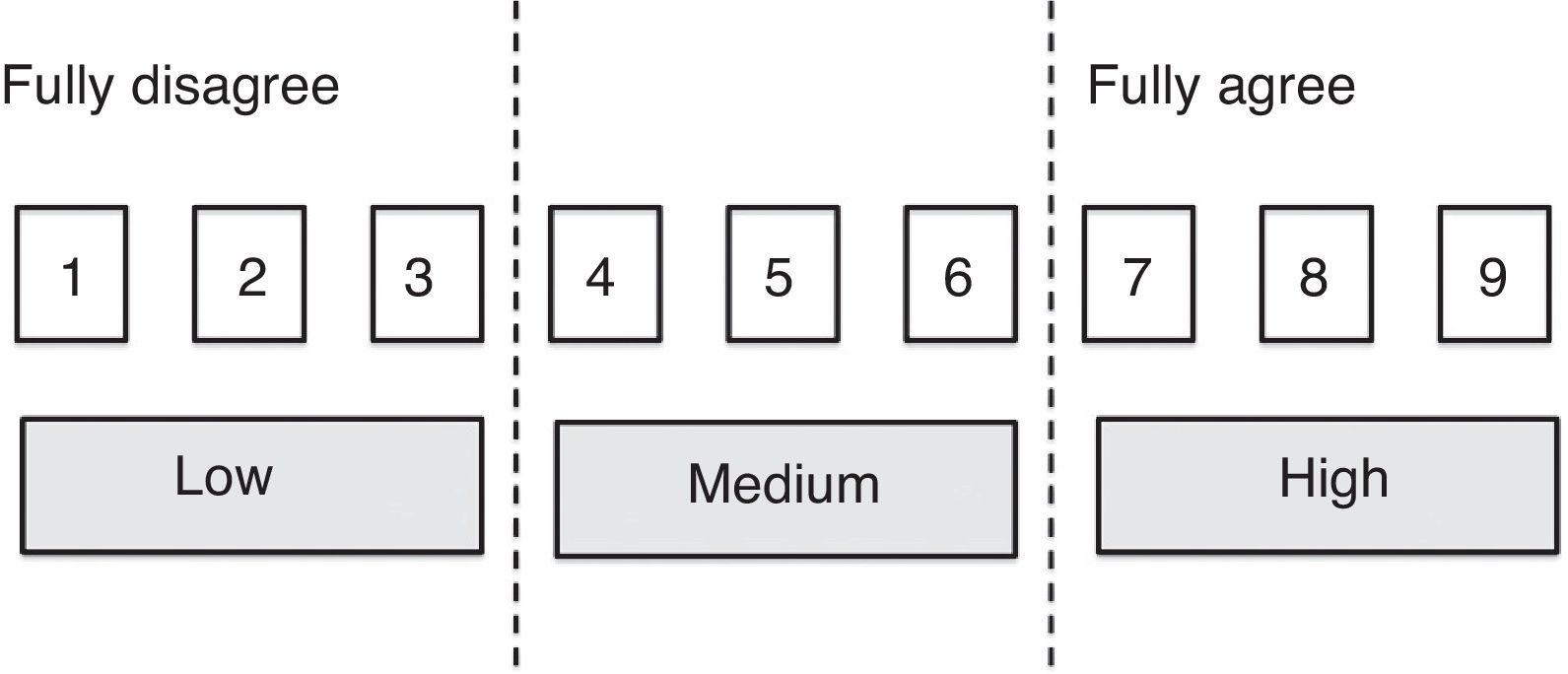

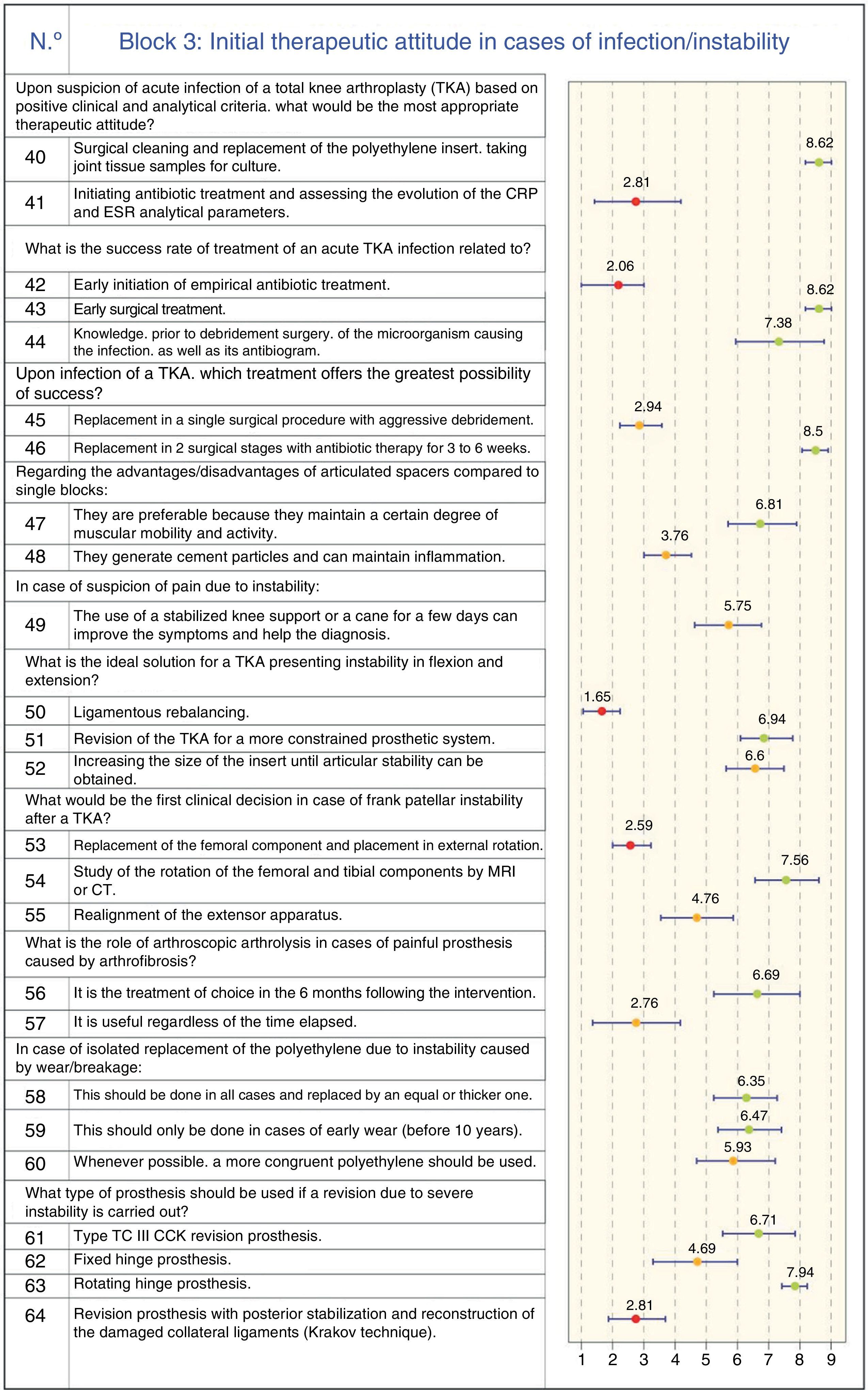

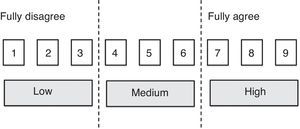

Contents and processing of the questionnaireAll consensus items (Fig. 1) were measured with the same Likert-type ordinal scale of 9 points with linguistic qualifiers (“agree/disagree”).

Assessment criteria- •

1–3: I disagree with the statement (the lower the score, the greater the level of disagreement).

- •

4–6: I neither agree nor disagree with the statement; my opinion on the issue is not fully defined (4 or 6 were chosen depending on whether one was probably closer to disagreement or agreement, respectively).

- •

7–9: I agree with the statement (the higher the score, the greater the level of agreement).

The position of the median scores within the group and the level of agreement reached by the respondents were used to analyze the opinion of the group and the kind of consensus reached on each question, according to the following criteria: an item was considered consensual when there was “concordance” in the opinion of the panel, that is, when the number experts who scored it outside the 3-point region containing the median1–9 was less than a third of respondents. In this case, the median value determined the consensus reached by the group: majority “disagreement” with the item if the median ≤3 or majority “agreement” with the item if the median ≥7. Cases in which the median was in the 4–6 region, were considered as “doubtful” items. On the other hand, we established that there was “discordance” among the panel when the scores of one-third or more of the panelists were in the 1–3 region, and the scores of another third or more were in the 7–9 region. The remaining items, in which there was neither agreement nor disagreement, were considered to have an “unspecified” level of consensus. All items on which the group did not reach a clear consensus in favor or against the issue under consideration (doubtful items, those on which there was discordance and those which showed an “unspecified” level of consensus) were proposed for reconsideration by the panel in the second Delphi round. Items on which there was a high dispersion of opinions among respondents, with an interquartile range ≥4 points (range of scores contained between the p25 and p75 values of the distribution), were also reassessed.

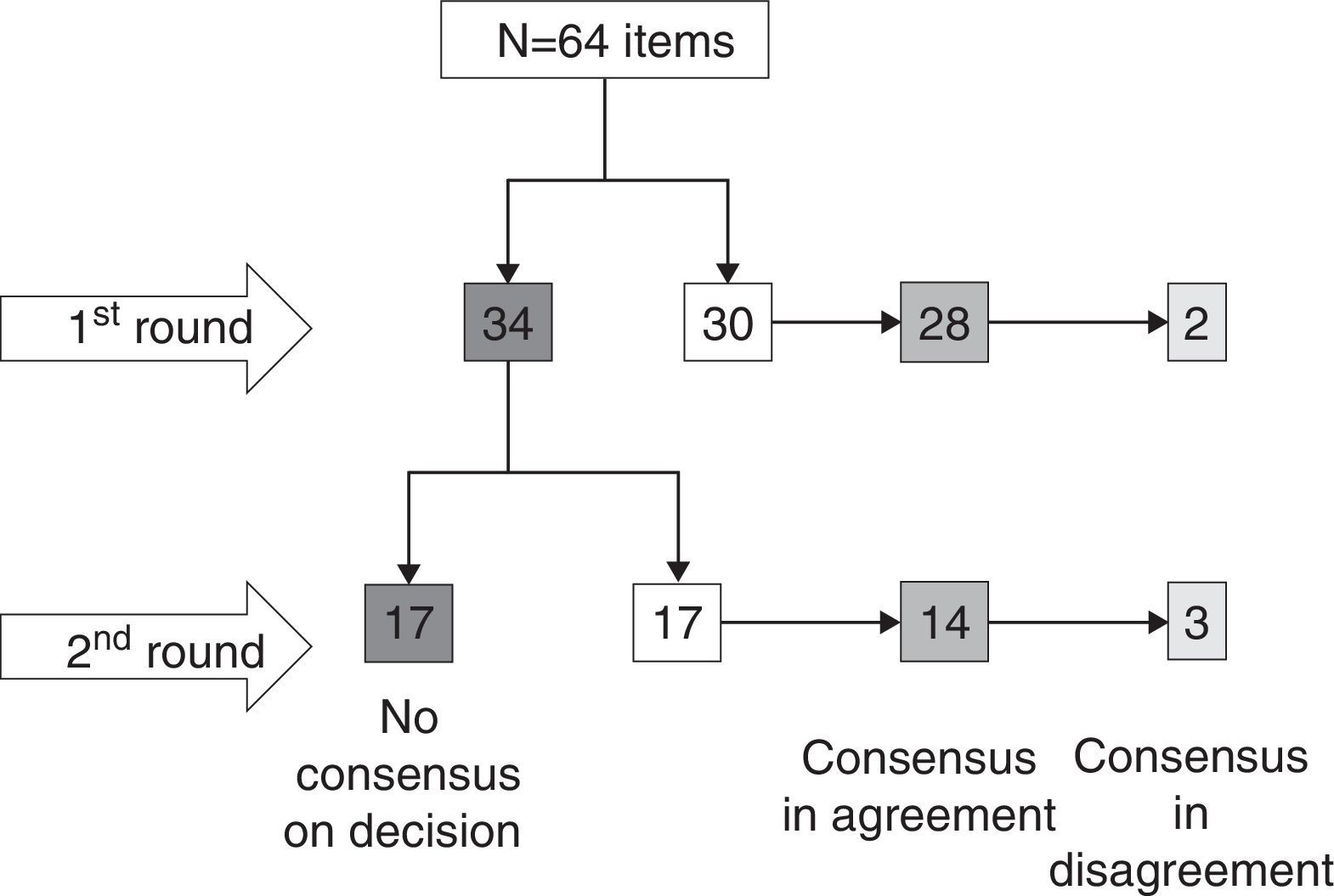

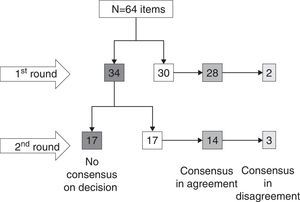

ResultsOf the 64 items proposed, there was sufficient consensus, either as agreement or disagreement, on 30 of them in the first round. Out of the 34 which were reassessed in the second round, a consensus was reached in only 17 cases (Fig. 2). In short, there was agreement with the proposed item in 42 cases (65.6%), disagreement in 5 (7.8%), and there was no consensus on the issue proposed in 17 cases (26.6%).

Therefore, those items on which there was a broad consensus, either in favor or against the proposal, were useful for this work and were the ones used to draw definitive conclusions, supported by the available literature.

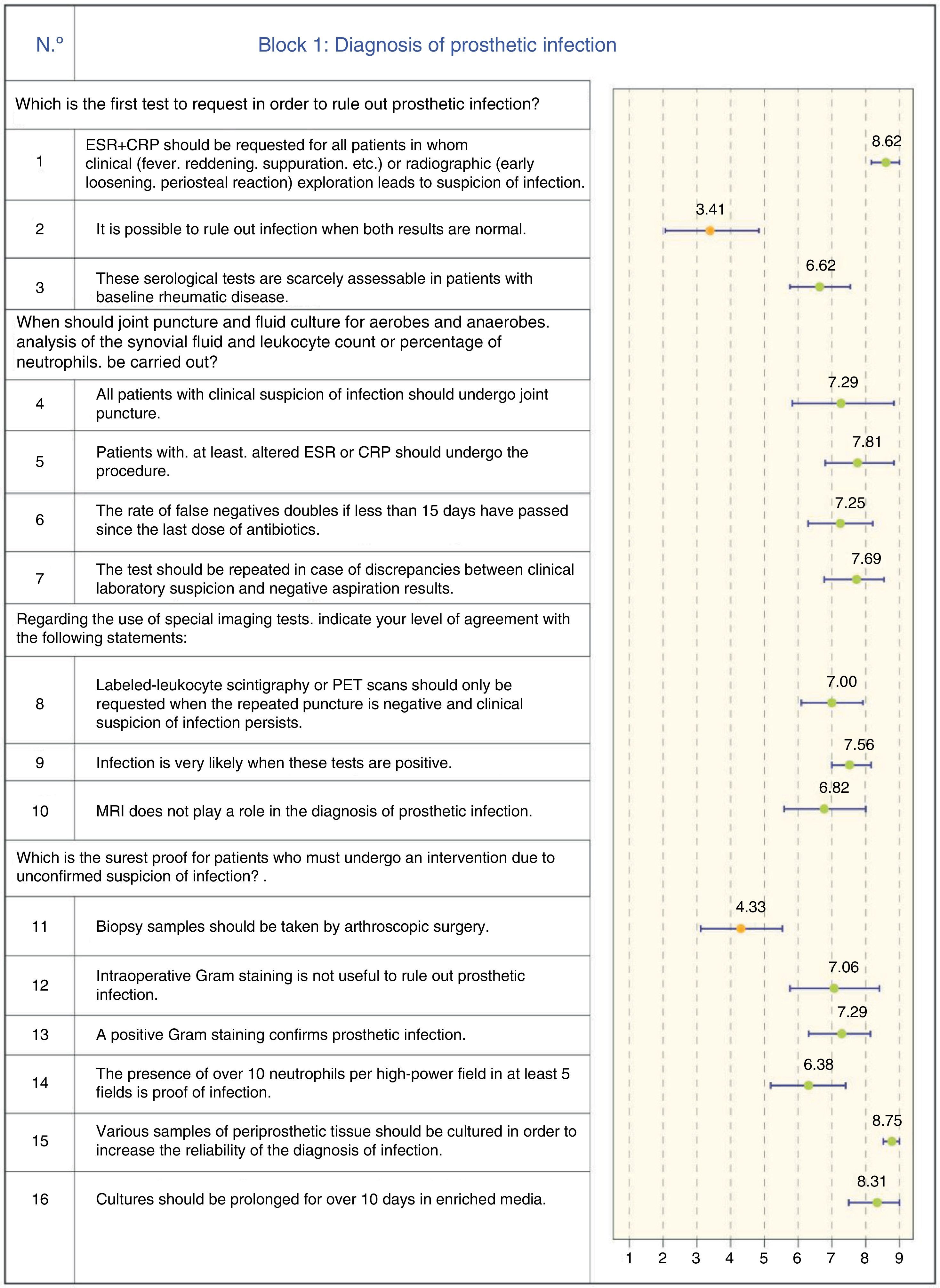

The level of agreement on each of the proposals or items is shown in Figs. 3–5, corresponding to the 3 controversial aspects related to painful knee arthroplasty selected by the Scientific Committee.

ConclusionsDiagnosis of prosthetic infectionProsthetic infection should be the first cause to be ruled out when faced with a painful knee prosthesis. It is vital to obtain an early diagnosis in order to initiate a specific treatment with chances of success. The clinical diagnosis is based on suspicion caused by clinical signs of fever, suppuration or inflammation in the joint, or else radiographic signs of early loosening or periosteal reaction.

C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate have a high negative predictive value and must be the first tests requestedThere are many tests available to detect infection, but it is a unanimous opinion among the panelists that C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) should be the first tests requested, jointly, upon clinical suspicion of infection. Nevertheless, we must bear in mind that some inflammatory or neoplastic processes can also increase these markers.8

Although there are some doubts among the participating specialists on the value of the combined negativity of both tests to rule out infection, the literature contains strong evidence of their higher negative predictive value (negative probability ratio: 0–0.6).9,10

Therefore, the recommendation is to carry out these 2 tests jointly in order to rule out infection with a high negative predictive value.8

Joint puncture is recommended when both tests are negative and suspicion persistsA large majority of panelists recommended joint puncture and aspiration for patients in whom both laboratory tests were positive. The fluid should be analyzed and cultured, provided that 2 weeks have elapsed since the last dose of antibiotics. In addition to a culture to identify the germ involved, synovial fluid analysis should also include a cell count. Various works have established different thresholds,11–13 but we can safely assume that a cell count over 3000cells/μL or over 65% neutrophils is highly suspicious of chronic prosthetic infection, although this has no value in acute phases where these figures may be temporarily increased.

In case of discrepancies between the results of this test and the analysis, the panel recommends repeating the punction.8,14

Labeled-leukocyte scintigraphy should only be used if the above tests are negative and there is clinical suspicion of infectionIf the clinical suspicion of infection persists and the repeated puncture remains negative, there is a strong consensus among the panel that the test which should be requested is labeled-leukocyte scintigraphy. The majority of the panel believes it to be highly reliable.15–17 Nowadays, scintigraphy with gallium and technetium has been displaced by leukocyte radiolabels,18 which today represent the gold standard imaging test for suspicion of infected prosthesis.

The panelists agreed that magnetic resonance imaging does not play a role in these patients. It is evident that, today, resonance imaging scans present significant distortions due to the presence of metallic material.

Positron emission tomography (PET) is still being developed for the field of diagnosis of infected arthroplasties.19

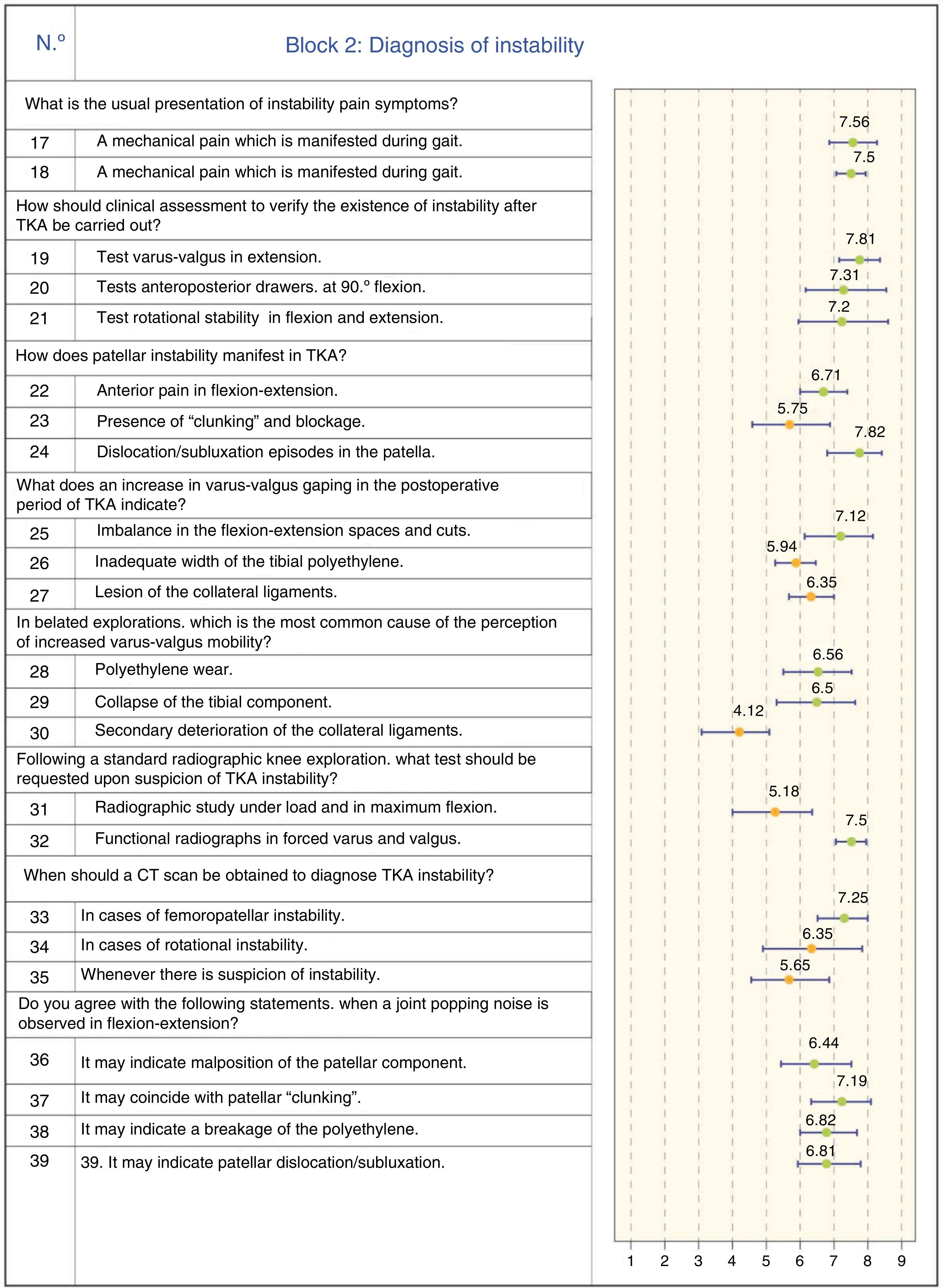

Diagnosis of prosthetic instabilityInstability after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is the cause of failure and subsequent revision in between 10% and 22% of all cases.20 Treatment achieves good results in many cases. However, if the causes of instability are not identified, the surgeon runs the risk of repeating the same mistakes and obtaining the same result, that is, another unstable prosthesis. Therefore, it is important to be very careful when confirming the diagnosis and to understand the causes of the problem.

Instability is manifested by pain upon load and gait, and the assessment of laxity should be carried out in all 3 planesA high level of consensus was reached regarding the observation that instability pain is primarily manifested during gait and in the standing position. Anterior knee pain after a TKA is a relatively common complaint among patients, but approximately 20% of cases were not satisfied with the final result regarding daily life activities.21

There was also a significant level of agreement regarding the exploration of joint instability in TKA, including the assessment of stability in extension, flexion and rotational stability. Physical examination of patients with an unstable TKA is helpful to identify the type of instability and its etiology. There are 3 main types of instability: instability in extension, instability in flexion and overall instability in addition to genu recurvatum.20,22

Preoperatively identifying patients at risk of suffering instability after undergoing a TKA (neuromuscular disease, hip or feet deformities, morbid obesity, etc.) would help to avoid creating this problem. The assessment should be carried out in a formal and exhaustive manner, in all planes, examining stability in extension, in 90° flexion, and in 30–45° intermediate and rotational arches.20,22

The fundamental sign of femoropatellar instability is dislocation/subluxationRegarding femoropatellar instability, there was a high level of consensus agreement that this pathological situation is defined by the observation of patellar dislocation/subluxation episodes. Anterior prosthetic knee pain should not be identified with patellar instability problems in flexion-extension, because it is usually due to other causes, such as internal rotation of the tibial component.23 The patellar “clunk” sign is related to overgrowth and fibrosis of suprapatellar soft tissues, which can become trapped in the anterior femoral shield during flexion-extension, especially with the posterior stabilized Insall-Burstein II prosthetic model type (Zimmer Inc., Warsaw, IN, USA), but it is not indicative of patellar instability.

Varus–valgus gaping in extension is a sign of imbalance in the creation of joint spaces, but its meaning is not clear to the panel for other reasonsThe responses only offered a high level of consensus regarding the significance of varus–valgus gaping in the immediate postoperative period when there was an imbalance in flexion-extension spaces. Agreement was scarce regarding the influence on this laxity of polyethylene thickness and lesions of the collateral ligaments.

It is true that increased gaping (varus/valgus) in extension clearly indicates iatrogenic injury of the collateral ligaments during surgery. This may require repair, reconstruction or increased constriction of the system. Nevertheless, it has been shown that conservative treatment is able to achieve the same mechanical stability, compared to cases where the ligament was intact.24

This same laxity detected at a later stage is more related to polyethylene wear or collapse of the tibial plateauThere was greater consensus on the cause of increased varus–valgus mobility, due to polyethylene wear or collapse of the tibial component, not being synonymous with ligamentous failure, and not requiring a more constrained implant. Regarding the causes of this instability, these may include aseptic loosening, bone loss due to collapse, fracture and polyethylene wear.22

Functional radiographs and a CT scan should always be requested upon suspicion of femoropatellar instabilityThis question generated a broad consensus regarding the request for a radiographic study with functional forced varus/valgus tests. On the other hand, there was no consensus about requesting a radiographic study with load and maximum flexion, despite the fact that it can be useful to assess polyethylene usury and anterior subluxation in case of posterior cruciate ligament failure for CR-type prostheses. Radiographs with load may be useful depending on the type of instability, and oblique radiographs can help to assess osteolysis present in femoral condyles.23

There was a significant consensus about requesting a CT scan upon suspicion of patellar instability. However, this consensus did not apply to requesting the test in case of suspected rotatory instability. CT scans can be very useful in the detection of internal malrotation of the femoral component, taking the epicondylar axis as a reference. They can also be useful to evaluate periprosthetic osteolysis, especially when a 3D CT scan is obtained.23

Joint popping sounds in flexion-extension indicate femoropatellar involvement or breakage of the tibial polyethylene componentThere was consensus regarding the 4 items of the question, although 3 of the questions related to patellar problems; misplacement, true subluxation/dislocation and the appearance of patellar “clunking”.24

In any case, the rate of complications related to the patellofemoral joint varies between 5% and 55%, and requires revision surgery in 29% of cases.23

Therapeutic approach in cases of painful total knee prosthesesSurgical cleaning and replacement of the polyethylene component are recommended in cases of acute infection. The initial antibiotic treatment should be abandonedAcute prosthetic infection is defined by local inflammatory signs and/or surgical wound drainage, with or without fever, with less than 4 weeks duration. Less frequently, it is due to hematogenous metastasis from a distant focus. In such cases it is known as late acute infection. Its symptoms are similar to septic arthritis in a native joint and it is important to ensure that the prosthesis worked properly before the onset of symptoms. Both types of acute infection, postoperative and acute hematogenous, should be treated with the same surgical procedure.25,26 This should consist in debridement and replacement of modular components which are not fixed to the bone, such as polyethylene inserts, with antibiotic treatment being initially contraindicated before surgery.

A negative Gram test does not serve to rule out infection. However, intraoperative biopsies are highly valuable to confirm infection during surgeryThe Gram test is not useful to rule out infection, especially when used as an intraoperative screening method. Several authors27,28 have reviewed the usefulness of this test for the diagnosis of infection and all have agreed that it should not be used as a routine method for the screening of infection, as it has a sensitivity of 19%, despite having a specificity of 98% and a positive predictive value of 63%. The latest guideline on prosthetic infection8 issued by the American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) contained a strong recommendation against the use of this test in the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection (Recommendation 11).

Regarding the intraoperative count of polymorphonuclear cells (PMN) for the confirmation of prosthetic infection, the cutoff value considered was 10 PMN/field in 5 different fields. A literature review10,29,30 showed that this test has a high positive predictive value, that is, the probability of infection is high when there are 10 or more PMN/field in 5 different fields. However, the fact that the count is less than 10 PMN, and specifically less than 5, does not rule out the presence of infection. The reduction of the threshold to 5 PMN count/field maintains a high sensitivity, but discretely decreases specificity, so it is advisable to maintain the criterion at 10 PMN/field in 5 different high-power fields.

Obtaining multiple cultures during the implantation of the revision prosthesis increases the probability of a diagnosis of infection and significantly reduces the rate of false negatives.31 The AAOS guideline recommendations on prosthetic infection8 consider that 5 intraoperative samples should be taken. Regarding transportation and culture, liquid material inoculated in blood culture vials obtains the best performance, followed by solid material. Certain studies recommend prolonging the conventional culture time in order to isolate slow-growing microorganisms, including Staphylococcus epidermidis, Propinobacterium acnes, etc., as these are, specifically, the microorganisms most frequently related to chronic prosthetic infection.32

In cases of chronic infection, the panel suggests replacement in 2 surgical stagesTreatment of chronic prosthetic infection involves replacing the implant. The 2 main reimplantation techniques are replacement in 1 and in 2 surgical stages.

After studying 29 articles and a total of 1641 patients, the review conducted by Langlais33 found that the highest rate of cures was obtained with replacement in 2 stages using antibiotic cement for prosthetic fixation. This percentage was 93% versus 86% obtained with replacement in 1 stage also using antibiotic cement.

More recent works, based on the Norwegian registry,34 also found survival rates of 98% at 2 years with replacement in 2 stages, compared to 89% with replacement in 1 stage. Therefore, replacement in 2 stages is currently considered the gold standard for the treatment of chronic prosthetic infection.

Although there was no consensus, instability in flexion and extension should improve after replacing the polyethylene by a thicker part, as supported by the literature35The objective of bone resection is to create an identical space in flexion and extension.36 This should be rectangular rather than trapezoidal, according to the works by Laskin,37 who showed that they offered more mobility, less medial pain and less need for lateral retinacular release. The tension in both ligamentous complexes will determine the stability of the space in flexion and extension. Tibial shape equally affects the flexion and extension spaces, and therefore, the thickness of the polyethylene insert will be crucial to confer tension to the soft tissues and medial and lateral ligamentous complexes.35,38

We must bear in mind that an excessive increase in the height of the polyethylene can cause low patella and, conversely, a decrease in the thickness of the insert can generate instability, both in flexion and extension.39

A computed tomography scan should be obtained before surgery upon clinical suspicion of patellar instabilityFemoral rotation is essential in order to obtain a rectangular space in flexion. Failure to achieve adequate external rotation leads to alterations in the patellar path, instability and anterior knee pain.40,41 There are 2 methods to obtain an adequate rotation of the femoral component: the first is to start by cutting the tibia and then making the posterior femoral cut parallel to this.42 The second method is based on using the epicondyles, Whiteside's line and posterior condyles as anatomical references. The Perth protocol is routinely used to study the rotation of components in knee arthroplasty. The rotation of the femoral component is measured relative to the epicondylar line and that of the tibial component relative to the posterior tibial condyles and anterior tuberosity.43

Arthrolysis performed within the first 6 months is the recommended option in cases of postoperative stiffnessOnce the diagnosis of knee stiffness has been established, the etiological factor must be identified. The medical history will help to detect the onset of healing problems, presence of superficial infection in the immediate postoperative period, trauma, and the pattern of occurrence of rigidity.44 Symptoms occurring in the immediate postoperative period will indicate that the problem may be surgical error or inadequate rehabilitation, whereas late-onset stiffness after a period of satisfactory mobility should point to cementing problems or a latent infection process.

The treatment for cases of early rigidity includes aggressive rehabilitation with adequate and sufficient analgesia with the aid of dynamic splints and, if necessary, before the first 8 weeks, manipulation under anesthesia provided there are no prosthetic malpositioning errors.45,46 Open arthrolysis involves radical debridement with release of the posterior cruciate ligament, balancing of soft tissues, section of the external wing and, if necessary, a relaxation of the extensor apparatus, either through quadricepsplasty or osteotomy of the anterior tibial tuberosity.44–47

Rescue using a thicker and, if possible, more congruent replacement is recommended in cases of isolated polyethylene wearThe duration of prosthetic implants is variable and subject to multiple circumstances. This is one of the main challenges faced by new designs and materials. Isolated wear of the polyethylene insert in prostheses with securely anchored components can be resolved by replacing the modular polyethylene component. If this is accompanied by osteolysis, it can be filled with an allograft, with good bone incorporation being reported.48 Griffin et al.49 obtained 84% good results in the replacement of modular polyethylene inserts in cases of implant wear and osteolysis with good fixation.

In any case, each joint must be evaluated individually, since some authors warn of a significant failure rate of these arthroplasties and a high number of revisions at 3 years of insert replacement.50

Finally, the group recommendation in cases of severe instability is the use of a “constrained condylar” or rotational hinge-type prosthesis over other optionsKnees with significant varus or valgus deformities, history of trauma or revision surgeries associated with significant bone loss present ligamentous deficiencies which require more constrained prosthesis models.

Intact and competent collateral ligaments are a prerequisite for the indication of primary knee prosthesis.51 Otherwise, the indication of condylar models carries a high failure rate in the short term.52 Furthermore, the reintegration or retensing of the lateral ligaments has been attempted by different methods, with very poor results which do not encourage further attempts with such techniques.53

Posterior stabilized or constrained rotational prostheses are indicated in different scenarios involving posterior cruciate ligament deficiencies or complex instabilities.53 However, posterior stabilized models do not offer sufficient stability in cases of large deformities, muscle atrophy, severe lesions of the extensor apparatus, need for large exposures to treat stiffness and other scenarios derived from revision surgery. In these cases it is necessary to use rotatory, constrained modular models.39

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence v.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data and that all patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this work does not reflect any patient data.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Juan Ramón Amillo Jiménez

Fermín Aramburo Hostench

Fernando Baro Pazos

Pablo Cañete San Pastor

Luis Díaz Gallego

Alejandro Espejo Baena

Raúl García Bógalo

Eduardo García Rey

Primitivo Gómez Cardero

José Antonio Hernández Hermoso

Gloria López Hernández

Luis M.a Lozano Lizarraga

Francisco Maculé Beneyto

Juan Carlos Martínez Pastor

Ferrán Montserrat Ramón

Rafael Muela Velasco

Alfonso Rayo Sánchez

Josep M.a Segur Vilalta

Abelardo Joaquín Suárez Vázquez

Jusep Tuneu Valls

Manuel Villanueva Martínez

Please cite this article as: Vaquero J, Macule F, Bello S, Chana F, Forriol F. Consenso SECOT sobre artroplastia de rodilla dolorosa. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2013;57:348–358.