To analyse the effectiveness and safety of rivaroxaban vs. standard treatment (ST) in the prevention of venous thromboembolism after hip or knee replacement in daily clinical practice in Spain.

Material and methodA sub-analysis of the Spanish data in the XAMOS international observational study that included patients >18 years who received 10mg o.d. rivaroxaban or ST. Follow-up: up to 3 months after surgery. Primary outcomes: incidence of symptomatic/asymptomatic thromboembolic events, bleeding, mortality, and other adverse events; secondary outcomes: use of health resources and satisfaction after hospital discharge.

ResultsOf the total 801 patients included, 410 received rivaroxaban and 391 ST (64.7% heparin, 24.0% fondaparinux, 11% dabigatran). The incidence of symptomatic thromboembolic events and major bleeding was similar in both groups (0.2% vs. 0.8% wit ST and 0.7% vs. 1.3% with ST [EMA criteria]/0.0% vs. 0.3% with ST [RECORD criteria]). The adverse events incidence associated with the drug was significantly higher rivaroxaban (overall: 4.4% vs. 0.8% with ST, P=.001; serious: 1.5% vs. 0.0% with ST, P=.03). The rivaroxaban used less health resources after discharge, and the majority considered the tolerability as “very good” and the treatment as “very comfortable”.

DiscussionRivaroxaban is at least as effective as ST in the prevention of venous thromboembolism prevention in daily clinical practice, with a similar incidence of haemorrhages. It provides greater satisfaction/comfort, and less health resources after discharge. These results should be interpreted taking into account the limitations inherent in observational studies.

Analizar en la práctica clínica diaria española la efectividad y seguridad de rivaroxaban vs. el tratamiento estándar (TE) en la prevención del tromboembolismo venoso tras artroplastia de cadera o rodilla.

Material y métodoSubanálisis de datos españoles del estudio observacional internacional XAMOS, que incluyó a pacientes>18 años que recibieron 10mg o.d. rivaroxaban o TE. Seguimiento: hasta 3 meses tras la cirugía. Variables primarias: incidencia de eventos tromboembólicos sintomáticos/asintomáticos, sangrados, mortalidad, otros acontecimientos adversos; variables secundarias: consumo de recursos sanitarios/satisfacción tras el alta.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 801 pacientes: 410 recibieron rivaroxaban y 391 TE (un 64,7% heparina, un 24% fondaparinux y un 11% dabigatran). La incidencia de eventos tromboembólicos sintomáticos y de sangrado mayor fue similar en ambos grupos (0,2 vs. 0,8% con TE y 0,7 vs. 1,3% con TE [criterios EMA]/0 vs. 0,3% con TE [criterios RECORD]). La incidencia de acontecimientos adversos relacionados con el fármaco fue significativamente superior con rivaroxaban (globales: 4,4 vs. 0,8% con TE [p=0,001]; graves: 1,5 vs. 0% con TE [p=0,03]). El grupo rivaroxaban consumió menos recursos sanitarios tras el alta y consideró la tolerabilidad «muy buena» y el tratamiento «muy cómodo» en una proporción mayor.

DiscusiónRivaroxaban es al menos tan efectivo como el TE en la prevención del tromboembolismo venoso en la práctica clínica diaria, con una incidencia similar de hemorragias. Aporta mayor satisfacción/comodidad, y menor gasto de recursos sanitarios tras el alta. Estos resultados han de ser interpretados considerando a las limitaciones inherentes a los estudios observacionales.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a severe condition, often asymptomatic, which is frequent among patients who have undergone knee or hip arthroplasty.1 Due to its chronic nature, its frequent recurrences and associated complications, VTE has a significant impact on patients2 and is associated to high morbidity and mortality.3 Its management consumes a significant amount of healthcare resources.4 Progressive population ageing, which will entail an increase of hip and knee arthroplasties, will contribute in a notable manner to increase the considerable load of VTE on society.3 Prevention of VTE could represent an essential pillar in the reduction of its consequences.

Nowadays, the need for perioperative thromboprophylaxis in surgery patients is unquestionable.5,6 There are currently drug treatments like low molecular weight heparins, vitamin K antagonists, unfractionated heparin, fondaparinux and, more recently, new direct oral anticoagulants. However, the evidence related to the effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants in real clinical practice conditions, usually very different from the ideal conditions of clinical trials, is limited.

The international phase IV study XAMOS (XArelto in the prophylaxis of postsurgical VTE after elective Major Orthopaedic Surgery of hip or knee) was designed to analyse, in everyday clinical practice, the effectiveness and safety of rivaroxaban in patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty compared to other standard thromboprophylactic treatments (ST). This study, which has included 252 participating centres from 37 countries, as well as a total of 17,701 patients, has confirmed the risk-benefit profile of rivaroxaban observed during the RECORD phase III clinical trials program,7 in which a single daily dose of 10mg rivaroxaban was found to be more effective than subcutaneous enoxaparin, with a similar safety profile, among patients who had undergone hip (RECORD 1 and 2)8,9 or knee (RECORD 3 and 4)10,11 arthroplasties. This study also enabled an analysis of certain aspects that cannot be assessed during controlled clinical trials, like the use of healthcare resources.

International observational studies like XAMOS gather a large amount data from several countries and from a wide range of patient profiles, relating to healthcare standards and clinical actions guided by national or supranational institutions. This work presents the results obtained at Spanish centres participating in the XAMOS study, in order to analyse patient management and the effectiveness and safety of rivaroxaban compared to ST in the specific conditions of our medium.

Material and methodDesign and participantsXAMOS was a prospective, open, non-interventionist, multicentre study. Inclusion of patients took place between February 2009 and June 2011. The inclusion criteria specified patients who were aged over 18 years, scheduled to undergo hip or knee arthroplasty, in whom the decision had been taken to administer thromboprophylactic treatment and who had signed an informed consent document. The exclusion criteria were mainly based on the contraindications specified in the technical datasheets of the antithrombotic treatments administered in each country. The design and methodology of the XAMOS study have been described in detail previously,12 so only the most relevant aspects for the analysis of data collected in Spain will be listed below.

Each participating physician determined the type, dose and duration of each of the thromboprophylactic treatments administered and included a similar number of patients in both treatment groups. The study followed the regulations and recommendations relating to non-interventionist studies, good clinical practices and the applicable local laws and regulations. The study protocol was approved by the corresponding ethics committees/institutional review panels. Registration number: NCT00831714 (ClinicalTrials.gov).

Data collection and monitoringThe collection of patient data was structured into 4 visits. The baseline visit (inclusion in the study; V0) included collection of demographic and anthropometric data (age, gender, ethnicity, body mass index), medical history, previous concomitant diseases and drugs taken, and the site of the arthroplasty. Durante visit 1 (V1), which went from the moment when admitted patients underwent the surgical intervention and started thromboprophylactic treatment until hospital discharge, the following adverse events were collected (AE): arterial or venous symptomatic thromboembolic events, bleeding, non-common AE and mortality due to any cause. Severe AE were monitored until a final result thereof was obtained. AE were classified according to the MedDRA (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities) terminology. In addition, V1 also served to collect data on the intervention (type of surgery, mode of fixation, type of anaesthesia), time elapsed until the start of prophylaxis and its duration, time elapsed from the intervention until mobilisation and from mobilisation until hospital discharge, destination following discharge, preparations for the administration of thromboprophylactic treatment following discharge and training provided. So as to register any AE occurring after hospital discharge and the need for unscheduled medical visits, patients were monitored for a period between 1 week after completing prophylaxis (visit 2, V2) and 3 months after the surgery (visit 3, V3). The tolerability and perception by patients of the comfort of the treatment at the time of discharge and after completing the thromboprophylactic treatment were also recorded.

Assessment of adverse eventsThe main safety variable was the rate of major bleeding, defined according to the same criteria used in RECORD studies13: fatal bleeding or in a critical organ (intracranial, intraocular, intraspinal, pericardial, retroperitoneal, in a non-operated joint, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome) or requiring reintervention, or else clinically manifest bleeding in an extraoperative area associated to a decrease in haemoglobin ≥2g/dl (calculated from the initial postoperative value in day 1) or the need to infuse ≥2 units of full blood or erythrocyte concentrates. In addition, the definition established by the European Medicines Agency was also used.14 This is similar to the previous version, but includes cases of bleeding justifying an interruption of the treatment and cases of bleeding in the site of surgery, with the same criteria as the extraoperative. AE were classified as caused by the treatment when they began on the day of the first dose of thromboprophylactic treatment or subsequent to it, and up to 48h after the last dose.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was carried out using the statistics software package SAS System version 9.1.3 service pack 3. Categorical variables were expressed through percentages and compared using the Chi-squared or Fisher test, as appropriate. Quantitative variables were expressed through mean and standard deviation once their normal distribution had been confirmed, and were compared through the Student t test. This analysis was only carried out on variables that were considered relevant (characteristics of patients and effectiveness/safety variables), and where the number of instances enabled an analysis. The safety population included those patients who received at least one dose of thromboprophylactic treatment, whilst excluding patients who had revoked their informed consent, had been included retrospectively, had abandoned the treatment due to an AE prior to it, whose data collection notebook was not signed by the physician, or who had any other associated reason that justified exclusion. The level of statistical significance was established at P<.05.

ResultsCharacteristics of participantsA total of 801 patients from 15 centres in Spain were included in the study, all of them representing the safety population. Of these, 410 received rivaroxaban and 391 ST (64.7% low molecular weight heparin, 24% fondaparinux and 11% dabigatran). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. No significant differences were observed among patients in terms of age or gender. The average body mass index pointed to a high level of obesity/overweight, with no differences between both groups. The majority of patients presented at least one concomitant disease, with no differences between both groups (Table 1). Hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and diabetes mellitus were the most frequent in all cases (56.8%, 17.1% and 15.1%, respectively, in the rivaroxaban group; and 58.8%, 15.9% and 16.9%, respectively, in the ST group). More patients in the ST group suffered atrial fibrillation.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the surgical intervention and the thromboprophylactic treatment administered (safety population).

| Rivaroxaban (n=410) | Standard treatment (n=391) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 69.5 (10) | 69.2 (9.7) | 0.667* |

| Females, n (%) | 254 (62) | 246 (62.9) | 0.778** |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD)a | 30.1 (11.9) | 30.4 (4.9) | 0.668* |

| Patients with at least one concomitant disease, n (%) | 330 (80.5) | 317 (81.1) | 0.833*** |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 8 (2) | 19 (4.9) | 0.029** |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 9 (2.2) | 8 (2) | 1.000** |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | NA | ||

| Primary hip arthroplasty | 119 (29) | 132 (33.8) | |

| Primary total knee arthroplasty | 228 (55.6) | 236 (60.4) | |

| Revision of hip arthroplasty | 5 (1.2) | 6 (1.5) | |

| Revision of total knee arthroplasty | 57 (13.9) | 17 (4.3) | |

| Other | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Mode of fixation, n (%)b | NA | ||

| Cement | 290 (70.7) | 265 (67.8) | |

| Porous | 81 (19.8) | 87 (22.3) | |

| Hydroxyapatite | 34 (8.3) | 31 (7.9) | |

| Others | 5 (1.2) | 7 (1.8) | |

| Type of anaesthesia, n (%) | NA | ||

| General | 72 (17.6) | 90 (23) | |

| Neuraxial | 332 (81) | 297 (76) | |

| Peripheral | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Combinations of general and others | 6 (1.5) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Other combinations | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Time until the first dose of thromboprophylactic treatment (h), median (Q1–Q3)c | 7.6 (6–10.3) | 8.7 (6.5–12.2) | |

| Duration of prophylaxis (days), mean (SD)d | 35.5 (8.3) | 35.6 (9.9) | 0.877* |

BMI, body mass index; NA, not analysed; SD, standard deviation.

In total, 85% of the surgical interventions in the rivaroxaban group and 94% in the ST group were primary knee or hip arthroplasties (Table 1), in almost all cases unilateral (>99%). The predominant mode of fixation in both groups was cement. The most frequent type of anaesthesia was neuraxial (Table 1). The mean duration of the intervention was 1.62±0.49h in both groups. Only 4 patients (1%) in the rivaroxaban group and 2 in the ST group (0.5%) suffered complications linked to the surgical intervention.

Administration of thromboprophylactic treatmentThe mean period of time until the first dose of thromboembolic treatment was administered and the mean duration of the treatment were similar in both groups (Table 1). Nearly half of the patients received the first dose of thromboprophylactic treatment in the first 6–10h after the intervention (47.3% in the rivaroxaban group and 42.7% in the ST group). In both groups, the most common duration of treatment was 35–42 days (41.2% in the rivaroxaban group and 43% in the ST group). This was followed by a duration of treatment of 28–35 days, which was more frequent in the rivaroxaban group (36.8% vs. 24.8% of patients in the ST group).

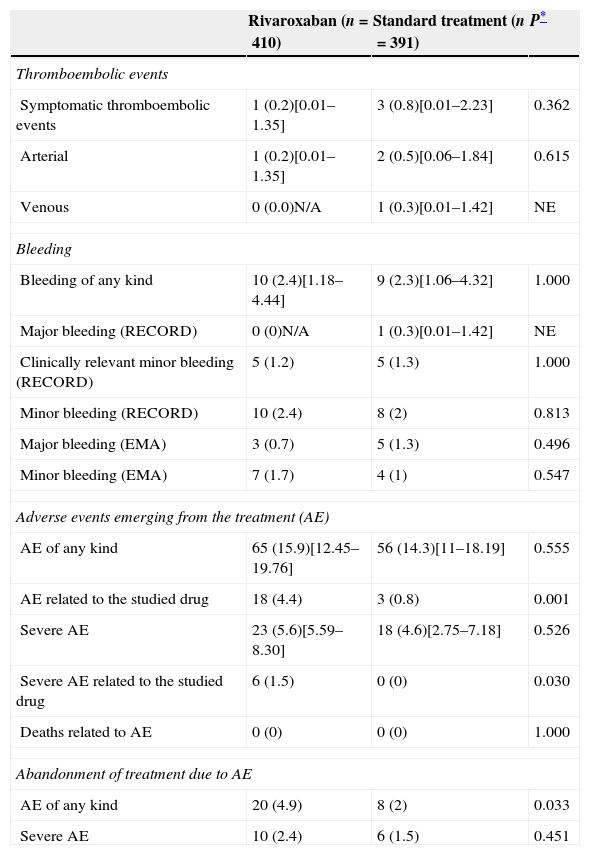

Clinical resultsThe number of thromboembolic events was similar in both groups (0.8% in the ST group vs. 0.2% in the rivaroxaban group, P=.362) (Table 2). The incidence of bleeding due to treatment was also similar in both groups, including that of major bleeding as defined by the EMA or RECORD criteria (1.3% and 0.3%, respectively, in the ST group vs. 0.7% and 0%, respectively, in the rivaroxaban group) (Table 2).

Incidence of symptomatic thromboembolic events, bleeding and other adverse events emerging from the treatment (safety population).

| Rivaroxaban (n=410) | Standard treatment (n=391) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thromboembolic events | |||

| Symptomatic thromboembolic events | 1 (0.2)[0.01–1.35] | 3 (0.8)[0.01–2.23] | 0.362 |

| Arterial | 1 (0.2)[0.01–1.35] | 2 (0.5)[0.06–1.84] | 0.615 |

| Venous | 0 (0.0)N/A | 1 (0.3)[0.01–1.42] | NE |

| Bleeding | |||

| Bleeding of any kind | 10 (2.4)[1.18–4.44] | 9 (2.3)[1.06–4.32] | 1.000 |

| Major bleeding (RECORD) | 0 (0)N/A | 1 (0.3)[0.01–1.42] | NE |

| Clinically relevant minor bleeding (RECORD) | 5 (1.2) | 5 (1.3) | 1.000 |

| Minor bleeding (RECORD) | 10 (2.4) | 8 (2) | 0.813 |

| Major bleeding (EMA) | 3 (0.7) | 5 (1.3) | 0.496 |

| Minor bleeding (EMA) | 7 (1.7) | 4 (1) | 0.547 |

| Adverse events emerging from the treatment (AE) | |||

| AE of any kind | 65 (15.9)[12.45–19.76] | 56 (14.3)[11–18.19] | 0.555 |

| AE related to the studied drug | 18 (4.4) | 3 (0.8) | 0.001 |

| Severe AE | 23 (5.6)[5.59–8.30] | 18 (4.6)[2.75–7.18] | 0.526 |

| Severe AE related to the studied drug | 6 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0.030 |

| Deaths related to AE | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Abandonment of treatment due to AE | |||

| AE of any kind | 20 (4.9) | 8 (2) | 0.033 |

| Severe AE | 10 (2.4) | 6 (1.5) | 0.451 |

NE, not evaluated.

The data are expressed as n (%) and 95% confidence interval [95% CI] when available.

The incidence of AE linked to the drug and severe AE (particularly those related to the drug) were significantly higher in the rivaroxaban group and caused a higher number of patients to abandon treatment (Table 2). The most frequent AE linked to the drug were those associated with damage, intoxication and complications deriving from the procedure, with an incidence of 5.1% in the rivaroxaban group and 2.6% in the ST group, although at an individual level, the incidence of each of the AE encompassed in this category did not show any differences and none were over 1%. They were followed in importance by infections and infestations (2.7% vs. 2.6%), gastrointestinal complications (2.5% vs. 1%), blood and lymphatic complications (anaemia) (1.7% vs. 1.5%) and general complications and at the site of administration (1.5% vs. 1.9%). No deaths linked to AE were recorded in any of the groups.

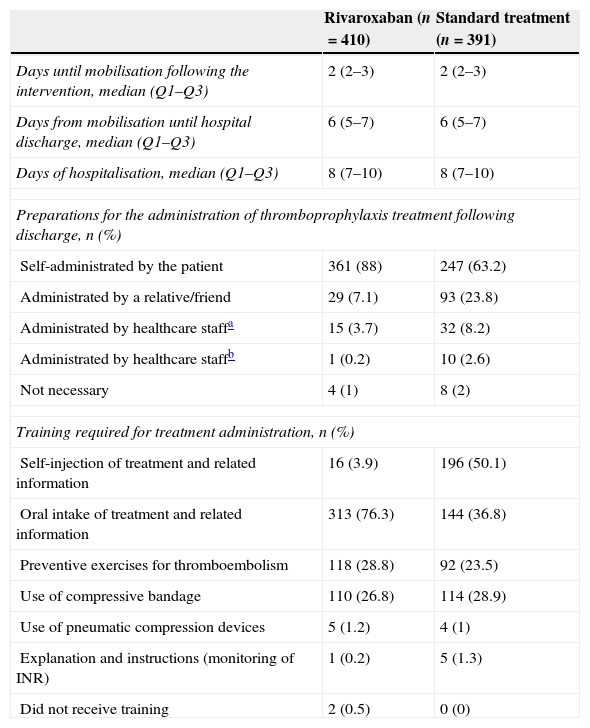

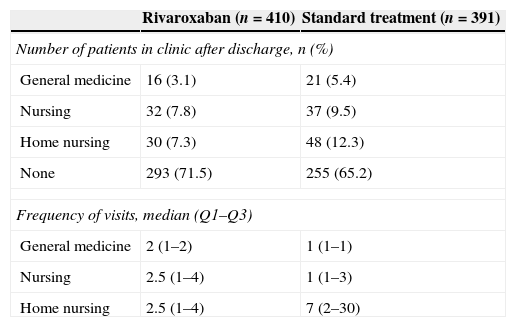

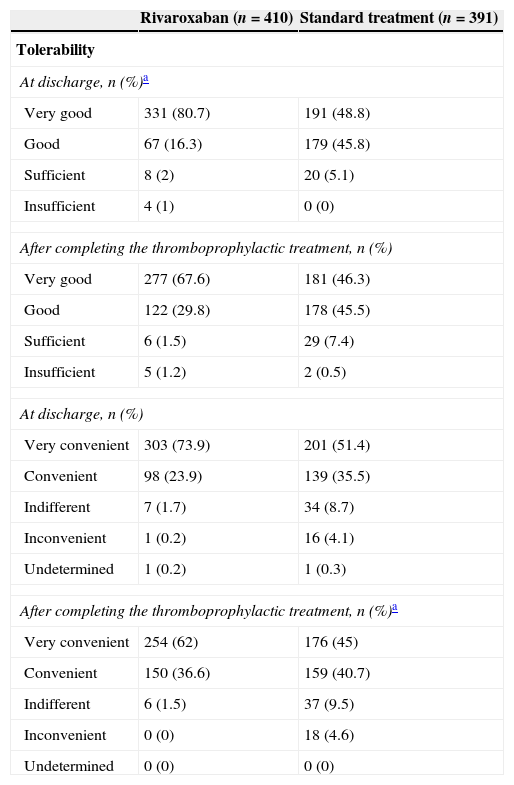

Table 3 presents the most relevant data about the postoperative period of patients until their hospital discharge. The median period until the start of mobilisation following the surgical intervention was 2 days in both groups. The median number of days from the start of mobilisation until hospital discharge and hospital stay was also similar (median of 6 and 8 days, respectively, in both cases). Following discharge, patients were moved to their homes in the majority of cases (92.6%), with no differences between both treatment groups. Patients in the ST group depended more on external help for the administration of thromboprophylactic treatment following discharge (Table 3) and also consumed more healthcare resources (Table 4). The tolerability was rated as very good at the time of hospital discharge by 80.7% of patients in the rivaroxaban group and 48.8% of patients in the ST group. These results underwent scarce variations until the end of the thromboprophylactic treatment. The treatment with rivaroxaban was described as “very convenient” by 73% of patients, versus 51.4% in the ST group. The differences levelled out, without reaching equality, after the end of the thromboprophylactic treatment (Table 5).

Data from the postoperative period until hospital discharge.

| Rivaroxaban (n=410) | Standard treatment (n=391) | |

|---|---|---|

| Days until mobilisation following the intervention, median (Q1–Q3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) |

| Days from mobilisation until hospital discharge, median (Q1–Q3) | 6 (5–7) | 6 (5–7) |

| Days of hospitalisation, median (Q1–Q3) | 8 (7–10) | 8 (7–10) |

| Preparations for the administration of thromboprophylaxis treatment following discharge, n (%) | ||

| Self-administrated by the patient | 361 (88) | 247 (63.2) |

| Administrated by a relative/friend | 29 (7.1) | 93 (23.8) |

| Administrated by healthcare staffa | 15 (3.7) | 32 (8.2) |

| Administrated by healthcare staffb | 1 (0.2) | 10 (2.6) |

| Not necessary | 4 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Training required for treatment administration, n (%) | ||

| Self-injection of treatment and related information | 16 (3.9) | 196 (50.1) |

| Oral intake of treatment and related information | 313 (76.3) | 144 (36.8) |

| Preventive exercises for thromboembolism | 118 (28.8) | 92 (23.5) |

| Use of compressive bandage | 110 (26.8) | 114 (28.9) |

| Use of pneumatic compression devices | 5 (1.2) | 4 (1) |

| Explanation and instructions (monitoring of INR) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1.3) |

| Did not receive training | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

INR, international normalised ratio.

Consumption of healthcare resources after discharge.

| Rivaroxaban (n=410) | Standard treatment (n=391) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients in clinic after discharge, n (%) | ||

| General medicine | 16 (3.1) | 21 (5.4) |

| Nursing | 32 (7.8) | 37 (9.5) |

| Home nursing | 30 (7.3) | 48 (12.3) |

| None | 293 (71.5) | 255 (65.2) |

| Frequency of visits, median (Q1–Q3) | ||

| General medicine | 2 (1–2) | 1 (1–1) |

| Nursing | 2.5 (1–4) | 1 (1–3) |

| Home nursing | 2.5 (1–4) | 7 (2–30) |

Tolerability and comfort of thromboprophylactic treatment.

| Rivaroxaban (n=410) | Standard treatment (n=391) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tolerability | ||

| At discharge, n (%)a | ||

| Very good | 331 (80.7) | 191 (48.8) |

| Good | 67 (16.3) | 179 (45.8) |

| Sufficient | 8 (2) | 20 (5.1) |

| Insufficient | 4 (1) | 0 (0) |

| After completing the thromboprophylactic treatment, n (%) | ||

| Very good | 277 (67.6) | 181 (46.3) |

| Good | 122 (29.8) | 178 (45.5) |

| Sufficient | 6 (1.5) | 29 (7.4) |

| Insufficient | 5 (1.2) | 2 (0.5) |

| At discharge, n (%) | ||

| Very convenient | 303 (73.9) | 201 (51.4) |

| Convenient | 98 (23.9) | 139 (35.5) |

| Indifferent | 7 (1.7) | 34 (8.7) |

| Inconvenient | 1 (0.2) | 16 (4.1) |

| Undetermined | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) |

| After completing the thromboprophylactic treatment, n (%)a | ||

| Very convenient | 254 (62) | 176 (45) |

| Convenient | 150 (36.6) | 159 (40.7) |

| Indifferent | 6 (1.5) | 37 (9.5) |

| Inconvenient | 0 (0) | 18 (4.6) |

| Undetermined | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Analysis of the data from Spanish centres participating in the international phase IV XAMOS study provides relevant information about the management of patients, the effectiveness and safety of rivaroxaban versus commonly used treatments for the prevention of thromboembolic events in patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty in our medium. These data reveal that thromboprophylactic treatment with rivaroxaban is associated to incidences of symptomatic thromboembolic events and bleeding similar to that of the ST used habitually. The incidence of AE related to the drug, both general and severe, was significantly higher with rivaroxaban compared to ST.

In the interpretation of these results it is important to take into account that the study population consisted in a subgroup of patients included in an international study, so there was a lack of determination of the sample size enabling an adequate statistical power, particularly if we take into account the low number of events analysed. In addition, some of the differences in the groups under study and surgical procedures applied to one or another could affect the interpretation of the results and are worthy of comment.

The characteristics of patients were similar in both groups, particularly advanced age (>69 years) and a mean body mass index pointing to obesity (30kg/m2). It is worth noting the higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the ST group, which could affect the incidence of arterial thromboembolic events. In spite of this, no differences were observed between both groups, which could be due to the low number of events. Furthermore, differences were observed in the type of surgery that would entail differences in thrombogenic risk. A superior use of rivaroxaban versus ST was noted among cases undergoing revision of total knee arthroplasty (13.9% vs. 4.9%), whereas there were no differences in terms of revision of hip arthroplasty. This surgical procedure has been associated to a higher thrombogenic risk than primary knee or hip surgery.15 Consequently, the use of ST as thromboprophylactic treatment was superior in the case of primary arthroplasties, both in knees and in hips. The type of anaesthesia used was another interesting aspect. Neuraxial anaesthesia was used more frequently in the rivaroxaban group (81% vs. 76%), and associated to a lower incidence of thromboembolic events,16 although this difference was not statistically significant. It is not known how this could have affected the results, given the low number of events.

Regarding safety, no differences were observed in the incidence of bleeding, both major and minor. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that there was a higher incidence of AE considered to be linked to the drug, both overall and severe, compared to ST (4.4% vs. 0.8% and 1.5% vs. 0%, respectively), which in addition caused a higher number of patients to abandon the treatment for that reason. The greatest differences were observed in terms of damage, intoxication and complications deriving from the procedure, although given the low incidence of each of the AE encompassed in this category (<1%) it was not possible to analyse the differences between both groups. No differences were observed between both groups regarding the incidence of any type of AE, including severe (whether related to the drug or not), which were comparatively much more frequent. Once again, the low number of AE related to the drug made it difficult to interpret the results. In any case, as long as there are no records from a more extensive patient population, it will be necessary to carry out an adequate follow-up. The AE observed most frequently with rivaroxaban coincided with those reported in the technical datasheet of the product.17 These aspects become particularly interesting when we take into account that, although the mean duration of thromboprophylactic treatment was similar in both groups (35.5±8.3 days in the rivaroxaban group and 35.6±9.9 days in the ST group), the percentage of patients in whom the treatment was extended up to 35 days was superior in the rivaroxaban group (36.8%) compared to the ST group (24.8%). Although the incidence of haemorrhage was not analysed based on the duration of thromboprophylaxis, the higher percentage of patients with prolonged thromboprophylaxis did not translate into a significant difference in the number of haemorrhagic events. It is unknown how this could have affected the incidence of AE related to the drug. The optimal duration of thromboprophylactic treatment is an aspect over which there is currently no consensus among the main reference guides.18 Although the guides of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the American College of Chest Physicians (AACP) recommend a duration of up to 35 days for hip arthroplasty,6,19 there is no agreement in terms of the optimal duration in knee arthroplasty: whereas the former recommends up to 14 days,19 the latter recommends up to 35 days (or 14 days with grade 2B evidence).6 In our country, the “Guide for thromboembolic prophylaxis in traumatology and orthopaedic surgery” (Guía de profilaxis tromboembólica en cirugía ortopédica y traumatología), promoted by the Thromboembolism Study Group (Spanish Traumatology and Orthopaedic Surgery Society, SECOT), available since 2003 and updated in 2007 and 2013,20 recommends prolonged prophylactic treatment (for 4–6 weeks) both in hip and knee arthroplasty. The convenience of extending the thromboprophylactic treatment has been expressed once again in a recent expert consensus conducted in our country, which established that prophylactic treatment in patients undergoing knee or hip arthroplasty should be maintained for up to 28–35 days.21

After hospital discharge, patients treated with rivaroxaban required less help for treatment administration from healthcare staff (including at their home), relatives or friends, and required less medical visits, which entailed savings of healthcare resources. As expected, patients in the ST group required more home visits by nursing staff, mainly due to the need for subcutaneous administration of low molecular weight heparin. The training received by patients was related to the treatment administered. Both the tolerability and comfort of the treatment were better valued by patients who received rivaroxaban.

In addition to the inherent limitations of observational studies, other significant limitations when interpreting these results have been commented in the text. It is also important to highlight that, in this study, the treatment decision followed the criteria of each physician, so the possibility is not ruled out that, occasionally, the indications did not follow the technical datasheet of the product, which are considered as indicative of recommendations. The number of “off label” cases is unknown, and patient inclusion criteria did not include a requirement that treatments were conducted according to the technical datasheet, so a certain degree of variability due to this aspect cannot be ruled out.

In summary, the Spanish data of the XAMOS study show that rivaroxaban is at least as effective as ST for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in daily clinical practice, providing greater comfort and lower use of healthcare resources after patient discharge. Although the incidences of major and minor haemorrhage were similar to those of ST, in spite of a higher proportion of patients treated for up to 35 days, the higher incidence of AE linked with the treatment by the researchers would advise an adequate follow-up of these cases until safety data from a more extensive patient population becomes available.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare having obtained written informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the work. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors wish to thank all the physicians participating in the XAMOS study in Spain for their collaboration. The authors also wish to thank Beatriz Viejo for her contribution in the drafting and editing of the manuscript. The present study has been funded by Bayer Healthcare.

Juan Antonio Alba. Clínica del Ángel de Málaga (Málaga)

Miguel Álvarez. Hospital Carlos Haya (Málaga)

Vicente Casa. Hospital de la Princesa (Madrid)

Pablo Díaz de Rada. Clínica Universitaria de Navarra (Navarra)

José Luis Díaz. Hospital General de Castellón (Castellón)

Francisco Goma. Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia (Valencia)

Claudio Gómez. Hospital Santa Ana de Motril (Granada)

Javier Granero. Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol (Barcelona)

Antonio Herrera. Hospital Miguel Servet (Zaragoza)

Luis María Lozano. Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (Barcelona)

Javier Martínez. Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón (Madrid)

José Luis Martínez. Hospital Virgen de the Nieves (Granada)

Antonio Murcia. Hospital Santa María del Rosell (Cartagena, Murcia)

Ángels Salvador. Hospital Plató (Barcelona)

José Ricardo Troncoso. Hospital Povisa (Vigo, Pontevedra)

The names of the researchers who participated in the XAMOS study in Spain are listed in Appendix.

Please cite this article as: Granero J, Díaz de Rada P, Lozano LM, Martínez J, Herrera A, en nombre de los investigadores del grupo XAMOS España. Rivaroxaban frente al tratamiento estándar en la prevención del tromboembolismo venoso tras artroplastia de cadera o rodilla en la práctica clínica diaria (datos de España del estudio internacional XAMOS). Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;60:44–52.