To review symptoms and imaging findings of proximal femoral osteoid osteomas (OO); to analyse the results of a thermal ablation technique for radiofrequency of the nidus in this location; and to describe usefulness of ultrasound guidance in selected cases.

Material and methodDescriptive and retrospective study consisting of 8 patients with OO in the proximal epiphysis of the femur, which were treated by thermal ablation of the nidus with radiofrequency waves from 1998 to 2004.

ResultsThe mean pain period until the performance of the thermal ablation was 11.5 months (range: 5–18 months). There were no complications, and all patients stated that the pain was gone by the day following the procedure, with some discomfort during the first week, except for one where it lasted more than one month due to technique difficulties. At present, with a mean follow up of 6 years and 2 months (range 6–190 months), all patients remain asymptomatic and live a rigorous normal life.

DiscussionThermal ablation with CT-guided radiofrequency waves is a safe, effective and efficient procedure.

ConclusionNormal appearance of a proximal femoral OO does not differ significantly from other location osteomas and its diagnosis is easier with previous knowledge. Thermal ablation of the nidus with radiofrequency waves, that may be performed using ultrasound guidance, appears to be the elective treatment of choice due to its efficiency and minimum morbidity.

Repasar la sintomatología y los hallazgos de imagen de los osteomas osteoides (OO) del extremo proximal del fémur, analizar los resultados de la técnica de la termoablación del nidus con ondas de radiofrecuencia en esa localización y describir la utilidad de la ecografía en la realización de la técnica en casos seleccionados.

Material y métodoEstudio descriptivo retrospectivo de una serie de 8 pacientes con OO del extremo proximal del fémur tratados mediante termoablación del nidus con ondas de radiofrecuencia desde 1998 hasta 2014.

ResultadosEl tiempo medio de evolución del dolor hasta la termoablación fue de 11,5 meses (rango: 5-18 meses). No hubo ninguna complicación y todos los pacientes refirieron la desaparición del dolor al día siguiente del procedimiento, con molestias que desaparecieron en la primera semana, salvo en uno, que se prolongaron más de un mes por la dificultad de la técnica. En la actualidad, con un seguimiento medio de 6 años y 2 meses (rango: 6-190 meses), todos los pacientes siguen asintomáticos y realizan una vida rigurosamente normal.

DiscusiónLa termoablación con ondas de radiofrecuencia guiada por TC es un procedimiento seguro, eficaz y eficiente.

ConclusionesLa presentación habitual de un OO del extremo proximal del fémur no difiere significativamente de la de un OO de otra localización y el diagnóstico es fácil cuando aquella se conoce. La termoablación del nidus con ondas de radiofrecuencia, que en casos seleccionados podría ayudarse de la ecografía para situar el electrodo en el centro del nidus, nos parece el tratamiento de elección por su eficacia y mínima morbilidad.

The osteoid osteoma (OO) is a relatively frequent benign bone-forming tumour. It represents approximately 10% of all benign bone tumours and is characterised by the presence of what is known as a “nidus”, a radiolucent central core less than 1.5cm in diameter; this nidus is formed of osteoid tissue abundant in nerve fibres and prostaglandins, which are somehow related with the local inflammation and pain that the patients experience.1

The lesion is generally diagnosed based on clinical data and characteristic images. It normally affects both men and women in the 2nd and 3rd decades of life and is usually found in the cortex of the long limb bone shafts, particularly in the femur and tibia. When it occurs in other bones, in other osseous segments, in the marrow or under the periosteum, where radiographic signs are less typical, diagnosis is usually delayed unless these signs are known and the disease is taken into consideration. For example, this is what happens with the proximal femur, where OO are found 25% of the time2,3 and where specific publications on this site usually consist of isolated cases3–6 or no details are given in the group of a series of cases in different locations.7–9 Follow-up of cases treated in this location is generally short, as well.

The first and principal objective of this study was to review the symptoms and imaging findings of OO in the proximal femur. The second objective was to analyse the results of using the technique of radiofrequency ablation of the nidus, based on our 16 years of experience. The third and last was to describe the usefulness of ultrasound guidance in this technique in selected cases.

Material and methodsThis was a retrospective descriptive study of a series of 8 patients with OO in the proximal femur treated using continuous radiofrequency ablation of the nidus in the Musculoskeletal Tumour Unit of the Hospital Clínico Universitario in Salamanca, when it existed, from 1998 to 2006, and in the Complejo Asistencial Universitario in León from July 2006 up to the present. A total of 8 patients with OO were treated in those 2 hospitals and during those time periods. All the patients comprising the study sample were diagnosed by clinical and imaging data, without anatomopathological confirmation, and all patients signed an informed consent for the treatment. Analysis was performed on epidemiological, clinical and imaging characteristics, the treatment applied and the results.

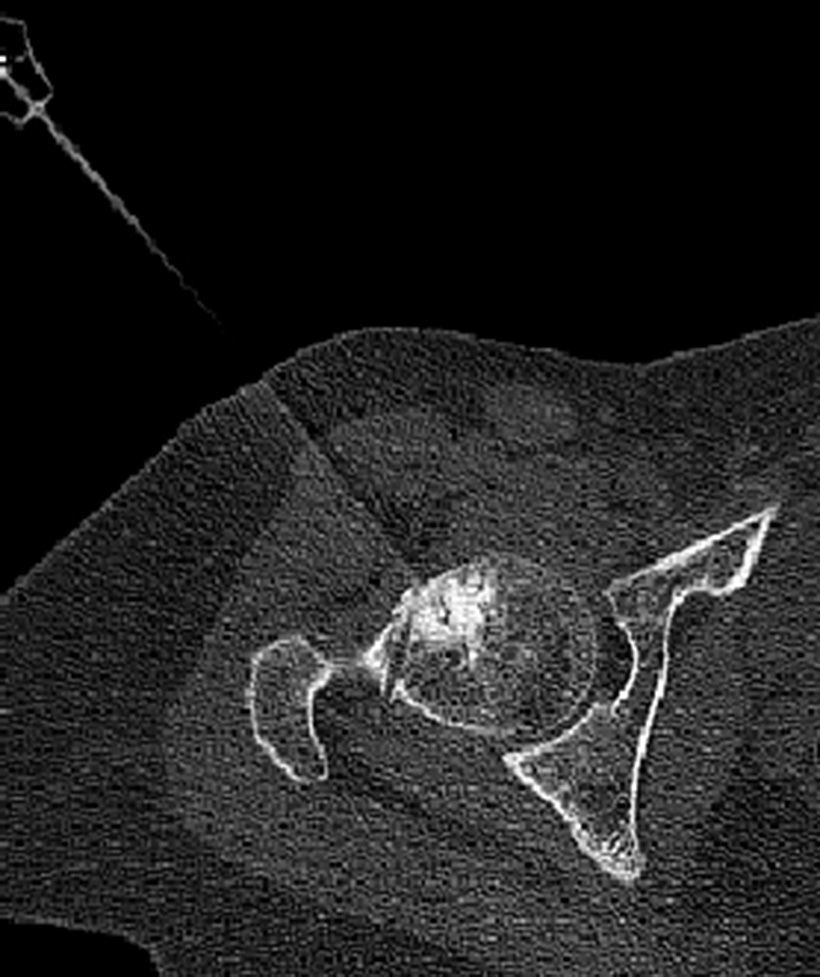

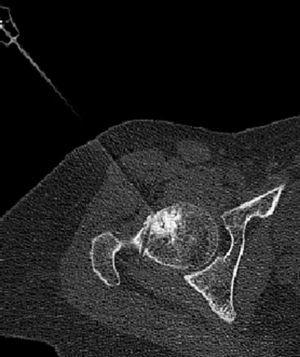

Radiofrequency thermal ablation techniqueAll the patients were operated on in the presence and with the participation of one of the study authors (LRRP) and with various radiologists and anaesthetists. The thermal ablation technique used in the first 3 cases of the series was described in 2010.10 In the other 5 cases, the electrode (Cool-tip™ RFA Single Electrode Kit, 14.4cm-0.7cm, Coviden IIc, Mansfield, MA, USA) was placed in the nidus either directly or through a tunnel created previously with a trocar (Figs. 1–3). In all the cases the thermal ablation was carried out in the computed tomography (CT) room in the Radiology Service at the corresponding hospitals, under regional anaesthesia and patient sedation. Twice (Cases 5 and 6), electrode placement was guided with ultrasound (8MHz linear probe, Xario ultrasound, Toshiba Medical, Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 2). Before thermal ablation (90°C for 6–7min), correct placement of the electrode in the centre of the nidus was confirmed by CT in all cases. In the first 3 cases a RFG-3CF radiofrequency wave generator (Radionics, Burlington, VT, USA) was used and, in the last 5, a Cool-tip™ RF ablation system (Radionics).

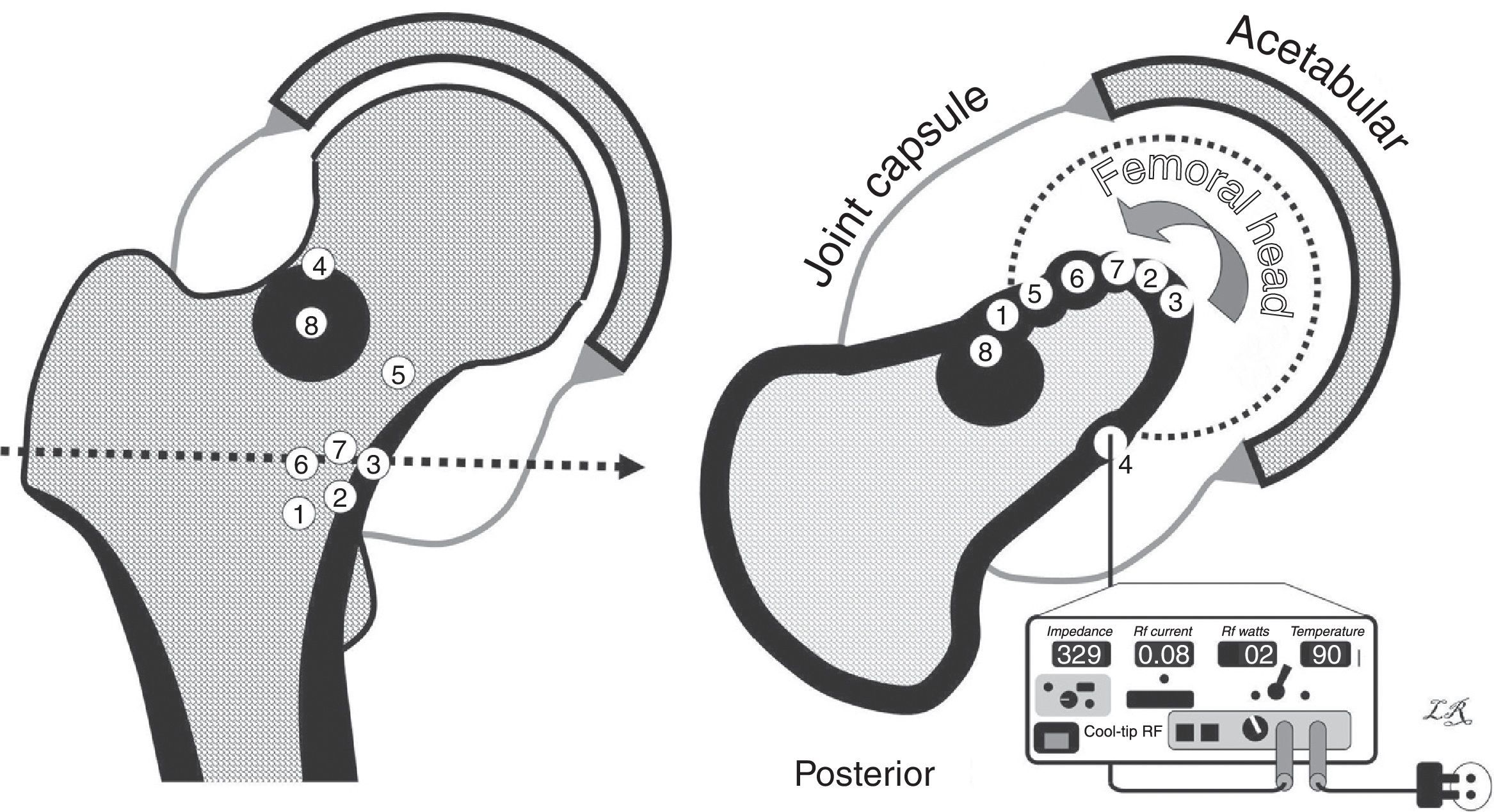

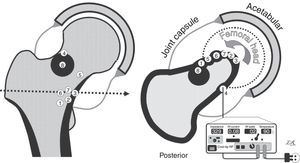

Drawings of the osteomas osteoids in our series. On the left, coronal view. On the right, axial view, with all the nidi projecting in the same cut (the numbers in the centre correspond to each case). The cortex and the reactive bone are shown in black, and the joint capsule in grey, with the joint cavity distended by the synovitis. The lower right section of the figure shows the radiofrequency device and the posterior approach to Case 4. The other cases were approached anteriorly, with more or less external limb rotation to make the nidus more accessible (curved arrow).

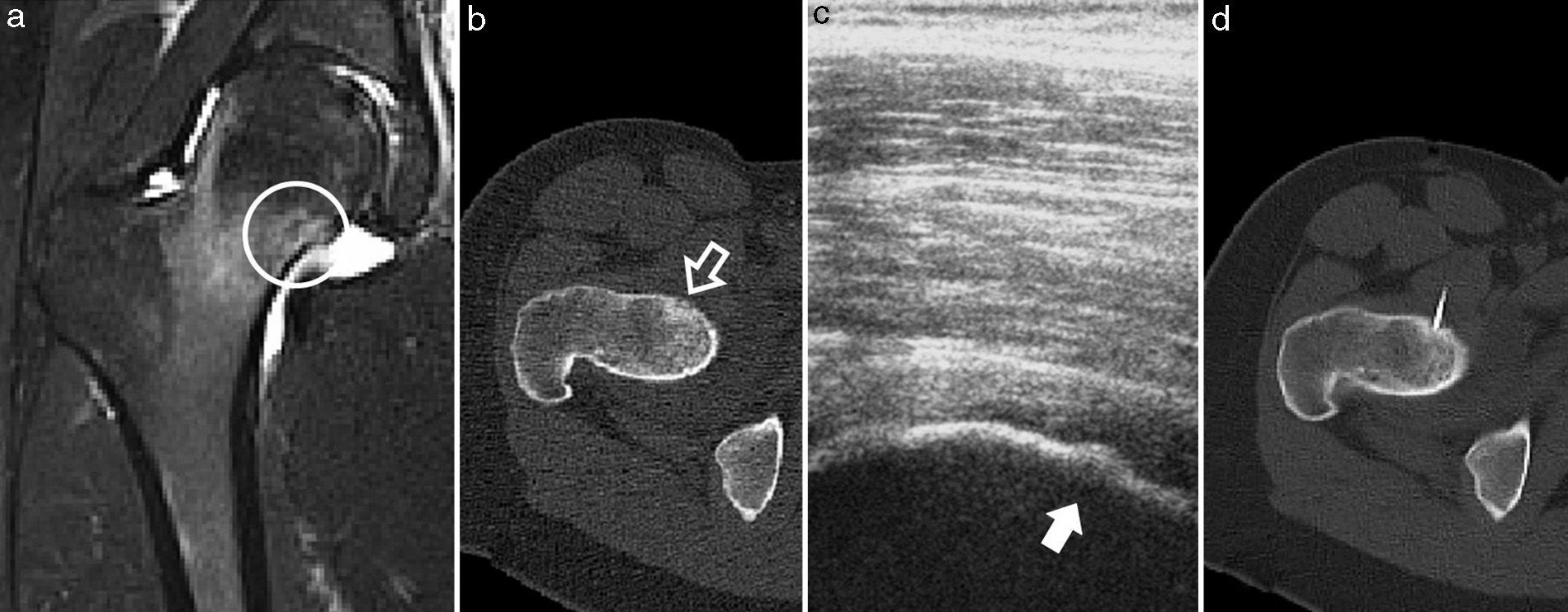

Case 5. (a) MRI in T2-weighted sequence of the proximal femur, with joint synovitis and osseous oedema, in whose bone core the nidus can be seen (circle); (b) CT axial cut, with the nidus in the anterior cortex of the femoral neck and slight endosteal bone formation (white arrow); (c) ultrasound monitoring during thermal ablation, with visualisation of the nidus in the bony cortex (dark arrow); (d) axial CT monitoring of the electrode located in the centre of the nidus.

All patients were discharged from hospital on the day after the intervention, walking without any external support. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were prescribed on demand and, as a precaution, all patients were recommended not to run and to avoid high-impact sport for 3 months. After that time, there were no physical restrictions of any type. Patients were followed up in external consultation at the end of 1, 3, 6 and 12 months following thermal ablation; in the present, patients were also interviewed by phone in connection with this study. In the external consultation each patient was asked about the presence of pain and the type of physical activity performed, and hip joint mobility was checked. In the phone interviews patients were asked about the presence of pain and the activity performed. No complementary imaging tests were carried out when clinical evolution was satisfactory, considering them unnecessary based on previous experience.7–9,11 Mean patient follow-up time was 6 years and 2 months (range: 6–190 months). No patient was lost during follow-up.

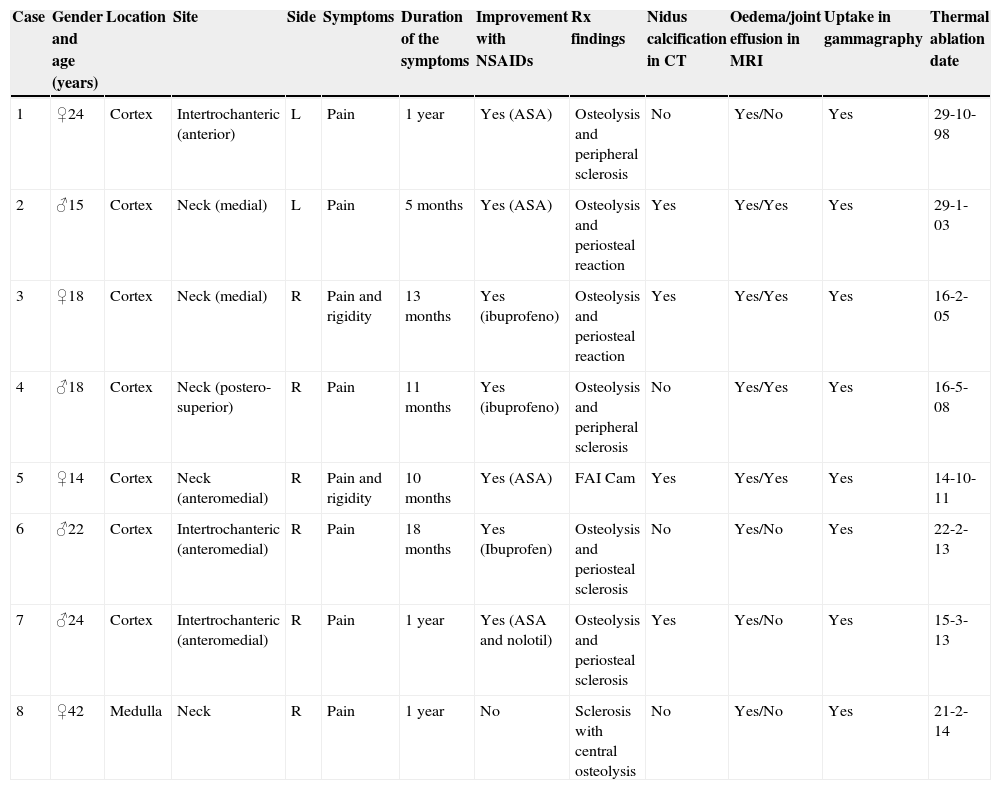

ResultsFour patients were male and 4, female, with a mean overall age of 22 years (range: 14–42 years). Mean pain evolution time until thermal ablation was 11.5 months (range: 5–18 months); 2 patients presented rigidity when examining hip joint mobility. The rest of the patient clinical and imaging data is summarised in Table 1. Fig. 1 presents the exact location for each case.

Clinical and imaging data from the patients in the series, with thermal ablation date.

| Case | Gender and age (years) | Location | Site | Side | Symptoms | Duration of the symptoms | Improvement with NSAIDs | Rx findings | Nidus calcification in CT | Oedema/joint effusion in MRI | Uptake in gammagraphy | Thermal ablation date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ♀24 | Cortex | Intertrochanteric (anterior) | L | Pain | 1 year | Yes (ASA) | Osteolysis and peripheral sclerosis | No | Yes/No | Yes | 29-10-98 |

| 2 | ♂15 | Cortex | Neck (medial) | L | Pain | 5 months | Yes (ASA) | Osteolysis and periosteal reaction | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | 29-1-03 |

| 3 | ♀18 | Cortex | Neck (medial) | R | Pain and rigidity | 13 months | Yes (ibuprofeno) | Osteolysis and periosteal reaction | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | 16-2-05 |

| 4 | ♂18 | Cortex | Neck (postero-superior) | R | Pain | 11 months | Yes (ibuprofeno) | Osteolysis and peripheral sclerosis | No | Yes/Yes | Yes | 16-5-08 |

| 5 | ♀14 | Cortex | Neck (anteromedial) | R | Pain and rigidity | 10 months | Yes (ASA) | FAI Cam | Yes | Yes/Yes | Yes | 14-10-11 |

| 6 | ♂22 | Cortex | Intertrochanteric (anteromedial) | R | Pain | 18 months | Yes (Ibuprofen) | Osteolysis and periosteal sclerosis | No | Yes/No | Yes | 22-2-13 |

| 7 | ♂24 | Cortex | Intertrochanteric (anteromedial) | R | Pain | 1 year | Yes (ASA and nolotil) | Osteolysis and periosteal sclerosis | Yes | Yes/No | Yes | 15-3-13 |

| 8 | ♀42 | Medulla | Neck | R | Pain | 1 year | No | Sclerosis with central osteolysis | No | Yes/No | Yes | 21-2-14 |

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; FAI, femoroacetabular syndrome/impingement; L, left; R, right.

There were no complications related to thermal ablation during the intervention or immediately afterwards. All patients reported that the pain disappeared on the day after the procedure and indicated that they had been able to sleep better than they ever had in the preceding months, although they did indicate some inguinal discomfort. One month after the intervention 7 patients were completely asymptomatic, reporting that the pain had disappeared in the first postoperative week; 1 patient (Case 8) continued having residual discomfort different from that suffered prior to the procedure, which was attributed to perforating the entire width of the femoral head with the trocar (Fig. 3). In this last case, the patient (a physician), resumed his professional activity with on-call duty 10 days after the intervention. All patients have remained asymptomatic and continue carrying out a completely normal life up to the present time, based on the later follow-ups.

DiscussionOsteoid osteomas are benign bone-forming tumours according to the World Health Organization classification. Without entering into OO etiopathogenesis (which is not under discussion in this article), the epidemiological, clinical, imaging, pathological and therapeutic aspects of these tumours are well known.1 Typical presentation is a young patient, usually male, with intense, piercing nocturnal pain, which improves with acetylsalicylic acid or other NSAID; the typical X-ray study reveals a solid periosteal reaction in the diaphysis of the femur or tibia, in which a rounded osteolysis (with or without calcification), corresponding to the nidus, can be seen indistinctly. This might be confirmed with a CT, while gammagraphy could show local increased uptake in that spot and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) would reveal typical OO findings. If OO diagnosis is easy in this context, in others (such as those of an intra-articular setting), it is more difficult and can be delayed, even for years. For example, in 4 cases published by Franceschi et al.,12 the delay ranged from 1 year to 10 years. Delay in diagnosis of proximal femur cases and, consequently, in their treatment, can be significant because (apart from the loss in patient quality of life) such delay could cause shortening and thickening of the femoral head, reduction in head height and early signs of osteoarthritis.3,5,13,14

In the proximal femur, when the nidus settles near the femoral insertion of the joint capsule, the lesion is considered intra-articular and develops with synovitis symptoms.15,16 The pain, which can be transferred to the inguinal area, buttock, thigh or knee, can seem different from the typical OO pain in another location17 and it is sometimes accompanied by limping, rigidity and muscle atrophy. Two of our patients displayed a significant loss of joint mobility, which was regained following treatment, although in our opinion the pain appeared similar to that of extra-articular OO.

With respect to complementary imaging findings, little or no reactive sclerosis could be seen in the simple X-ray, due to the absence of periosteum within the joint capsule2,4,5; however, in cases of lengthy evolution there could be thickening of the medial cortex proximal to the lesser trochanter and, rarely, prominent sclerosis.2 Discrete regional osteoporosis could also be seen, as well as interline hip joint thickening from joint effusion and chondral hypertrophy (Waldenstrom's sign).5 Gammagraphy, CT and MRI findings would be similar to those observed in OO in other sites, with some distinctive features.18 On the MRI there would be joint effusion, bone marrow oedema and yuxta-articular soft tissue oedema in 80%, 60% and 50% of the cases, respectively.2 Bone gammagraphy (although less safe in intra-articular sites) is also useful, with it being possible to find increased focal activity in the context of greater diffuse activity from the synovitis, hyperaemia and local osteoporosis.5

Although clinical presentation and imaging results might not be typical (which explains diagnostic confusion and frequent delays, often up to 2 years from symptom onset5,6,12,15,19), knowing about the condition makes its diagnosis easier and given earlier. In our series the mean time period until thermal ablation was almost a year, with at least partial response to anti-inflammatory drugs. A young patient who has pain in the site described and has presence of the previously-mentioned characteristics requires, first of all, a simple X-ray study in anteroposterior and axial projections. If a nidus is suspected in any of the X-rays or if no abnormality is seen, gammagraphy, CT or MRI should be performed; the tests can be carried out in the order preferred, taking into account their availability in each work setting. When the first test performed shows findings compatible with the suspected condition, the other tests should be requested. Gammagraphy would have been expected to show an area of increased uptake in 100% of the cases; MRI would show bone oedema; and CT, an unmistakable nidus. Then, with all the compatible data, the OO diagnosis can be established and treatment can be commenced without the need for a biopsy, which is a controversial practice.15,20,21 Factors against a biopsy would be the facts that it would make the procedure lengthier and more complex, as well as that it might not confirm the diagnosis in up to 75% of cases treated with minimally invasive techniques.21 In our opinion, in contrast to the standard of always performing one,9 the biopsy should be reserved for the few cases of doubtful diagnosis.

Specific comments should be given about diagnosis in Cases 4, 5 and 8 in our series. The first 2 cases highlight the need to differentiate the condition from femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI), with which it is sometimes confused because both conditions can be associated with bone oedema in MRI22 next to fibrocystic changes in the anterosuperior femoral neck-head junction.21 Case 4 is mentioned because the nidus was located in the site where the FAI pit hernia is also usually located, although it is normally placed more anteriorly than the placement of the nidus in our case. Case 5 stands out because the femoral head displayed an upper convexity that was reminiscent of cam-type FAI. The symptoms and imaging tests left no room for doubt in our cases, although OO had been considered in the second case in the differential diagnosis before reaching our unit. Case 8 was special in that, besides the patient being particularly older than is normal for the condition, the nidus was located in the medulla and there was excessive reactive sclerosis.23

Treatment options for OO include prolonged medical treatment, block resection and a set of minimally invasive percutaneous procedures that include nidus reaming (with or without ethanol injection, in a few juxta-articular cases by arthroscopy),14,24 laser photocoagulation and thermal ablation. Except for their use in selected cases, all these procedures currently include classic block resection because of its efficacy, technical simplicity, lower morbidity and more economical cost. In the intra-articular cases we are discussing, these advantages are even more evident. For example, we can consider what is represented by the osteochondroplasty with previous hip dislocation described by Shin et al.19

Introduced in 1992, CT-guided radiofrequency thermal ablation is now a well-known procedure, safety-demonstrated, effective and efficient in 76–100% of the cases.7,23,25,26 In addition, it can be repeated if the first attempt is unsuccessful.20,21 In our series all the patients became asymptomatic early, except for Case 8, in which the persistence of local discomfort was attributed to a technically-difficult procedure. Although the interval between thermal ablation and pain disappearance does not seem to predict a recurrence, pain persisting a month after the procedure certainly seems to indicate its failure.26

From a technical point of view, although there are medullary types of proximal femur OO15 with little periosteal reaction,27 the fact that most proximal femur OO cases are superficial (intra-cortex or subperiosteal) makes it easier, in selected cases, to pierce the nidus directly with a diamond-point electrode and to place it directly with ultrasound guidance. Ultrasound permits identifying the nidus as a signal slightly different in acoustic impedance from that of neighbouring cortex tissue, while a colour Doppler can also reveal subtle changes in vascular flow.28,29 The procedure is consequently simplified and the radiation patients receive is reduced, with high radiation levels being a problem that others have attempted to mitigate by using low-amperage tomodensitometry and more separated cuts.30

The main drawback of using ultrasound as a guide for thermal ablation is that its probe might not be sterile and could increase the risk of infection, which makes it necessary to pay special attention to strict asepsis measures. In our experience, with the exactitude of a programmed surgical intervention, the ultrasound technician first washes his/her hands and puts on sterile gloves; next, the probe (wrapped in a sterile compress) is picked up and applied over the patient's skin, respecting the electrode entry point, and the probe is directed towards the nidus with the other hand. Use of the CT is reduced to confirming the electrode position, so anaesthesia time and patient and staff radiation exposure are shortened.

With respect to technique complications, proximal femur cases (in contrast to those in other sites) are not associated with the difficulties of skin burns or damage to neighbouring neurovascular structures due to hip depth and the distance at which the main nerves and vessels are located in the region.3 However, there is a potential risk of avascular necrosis and, possibly, of fractures from temporal weakness of the femur neck. Although there is no consensus in this respect, we recommend a 3-month restriction from intense physical activity to avoid these risks, as Neumann et al.9 recommend partial load for 6 weeks for all lower limb cases treated.

Our study has several limitations. The first is its retrospective nature and the lack of comparison with other techniques. The second is the limited number of cases in the sample. The next, that the follow-up on one of the cases is short (6 months). The fourth is that there was no anatomical and pathological confirmation of any of the cases. The last limitation is that follow-up was carried out by telephone interviewing in the first cases of the series. We believe that these limitations do not bring the study conclusions into question, given the following considerations: based on what has been published in the scientific literature, the sample is sufficient; when recurrences occur, they usually happen before 7 months after the procedure,6,21 although there are also delayed cases9,30; histological confirmation of the diagnosis is unnecessary; and defining a successful result only requires knowing that the pain has not reappeared and that the patient is satisfied.8,9 Specific strengths of the study are that follow-up is longer than 6 years for 4 cases, and that the same professional participated in the diagnosis and treatment of all the patients.

In conclusion, the normal presentation of proximal femur OO does not significantly differ from that of a case of OO in another location and its diagnosis is easy when the condition is known. In our opinion, radiofrequency thermal ablation of the nidus (which, in selected cases, could be helped by using ultrasound to place the electrode in the centre of the nidus) is the treatment of choice because of its efficacy and minimal morbidity.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV. Level IV therapeutic study (case series).

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments have been performed on humans or animals for this study.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that their work centre protocols on publication of patient data have been followed.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained informed consent from the patients or subjects mentioned in this article. The corresponding author holds this document.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ramos-Pascua LR, Martínez-Valderrábano V, Santos-Sánchez JA, Tijerín Bueno M, Sánchez-Herráez S. Termoablación por radiofrecuencia de osteomas osteoides del extremo proximal del fémur. Utilidad de la ecografía en casos seleccionados. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:326–332.