Arthropathy of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint symptoms is very restrictive, and in some cases arthroplasty is required. In most of the reported series of PIP silicone arthroplasty, the technique described is the dorsal approach. As far as we know, the role of the volar approach in PIP arthroplasty has still not been adequately assessed.

ObjectivesTo retrospectively review the patients who had PIP joint arthroplasty, and to study the clinical and radiographic outcomes in relation to the approach: volar or dorsal.

MethodsA total of 22 PIP joint replacements were performed between 2005 and 2010. The mean age was 56 years and the mean follow-up period was 29 months. The implant used in all patients was the Avanta® PIP Soft-Skeletal Implant (Avanta Orthopaedics, San Diego, USA). The dorsal approach was performed in 14 joints, and a volar approach in 8 joints. The preoperative clinical evaluation included a visual analog scale (VAS) and the range of motion (ROM). The preoperative ROM mean was −15°/60° in both groups. The VAS and the ROM in the last follow-up visit were recorded and compared with preoperative values.

ResultsThe postoperative ROM of the dorsal approach group had a mean of −15°/60°, and that of the volar approach was −2°/62°.

ConclusionIt was found that the volar approach in this series offers the advantages of maintaining the integrity of the extensor mechanism, resulting in a complete restoration of the extension in the range of motion.

La artropatía de las articulaciones interfalángicas proximales (AIP) cursa con síntomas muy restrictivos, siendo algunos casos tributarios de artroplastia. En la mayoría de las series de artroplastias de las AIP la técnica utilizada es a través de un abordaje dorsal. El papel del abordaje palmar en la artroplastia de las AIP todavía no se ha valorado suficientemente.

ObjetivoRevisar retrospectivamente los pacientes intervenidos de artroplastia de la AIP, y determinar si las realizadas por vía palmar consiguen un rango de extensión mayor que las realizadas por vía dorsal.

Pacientes y métodosEntre 2005-2010 se realizaron 22 artroplastias de AIP. La media de seguimiento fue de 29 meses. El implante que se utilizó en todos los pacientes fue el implante de silicona de AIP modelo Avanta® (Avanta Orthopaedics, San Diego, California, EE. UU.). Se realizó un abordaje dorsal en 14 articulaciones y un abordaje palmar en 8. La valoración clínica preoperatoria incluyó la escala visual analógica (EVA) y el arco de movimiento. El arco de movimiento preoperatorio medio era de -15°/60° en ambos grupos. En la última visita del seguimiento, la EVA y el rango de movimiento se registraron y se compararon con los valores preoperatorios.

ResultadosEl arco medio de flexo-extensión postoperatorio del grupo del abordaje dorsal era de -15°/60°, y el del abordaje palmar de -2°/62°.

ConclusiónEn nuestra serie hemos observado que las artroplastias de AIP realizadas por vía palmar consiguen un rango de extensión mayor que aquellas realizadas por vía dorsal. El abordaje palmar ofrece las ventajas de mantener la integridad del mecanismo extensor.

Proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint arthropathy entails highly restrictive symptoms. Although many patients respond to conservative treatment, some cases require surgical treatment, even arthroplasty. The classical silicone implants introduced by Swanson in the 70s have demonstrated a significant reduction of pain and a discreet increase of the movement range.1 Subsequently, surface arthroplasties were introduced, which used chromium–cobalt as the proximal component and high-molecular weight polyethylene as the distal component.2 More recently, the use of implants with pyrolytic carbon components has been gaining acceptance.3–5 The results obtained both with the Swanson model and with more recent prostheses made of pyrolytic carbon are uniformly satisfactory.6–8 The PIP can be accessed through dorsal,2 lateral8 and volar7 approaches. The most commonly employed technique in most published PIP arthroplasty series has been the dorsal approach.9,3 The most frequent cause of reinterventions in PIP arthroplasties is extensor apparatus dysfunction.10 The volar approach offers several theoretical advantages over the dorsal approach. It offers surgeons the possibility of avoiding incisions on the extensor apparatus and, therefore, does not entail prolonged postoperative immobilization, thus almost eliminating the possibility of postoperative adherences and allowing rehabilitation to start almost immediately. The objective of this work was to retrospectively review patients undergoing PIP arthroplasty and to determine whether those conducted through a volar approach achieved a greater range of extension than those carried out through a dorsal approach.

Patients and methodsA total of 22 PIP arthroplasties were conducted on 17 patients between 2005 and 2010. Of these 14 were carried out through a dorsal approach and 8 through a volar approach. All the procedures were conducted by experienced surgeons from the Hand Surgery Unit of our center (C.L., I.P.).

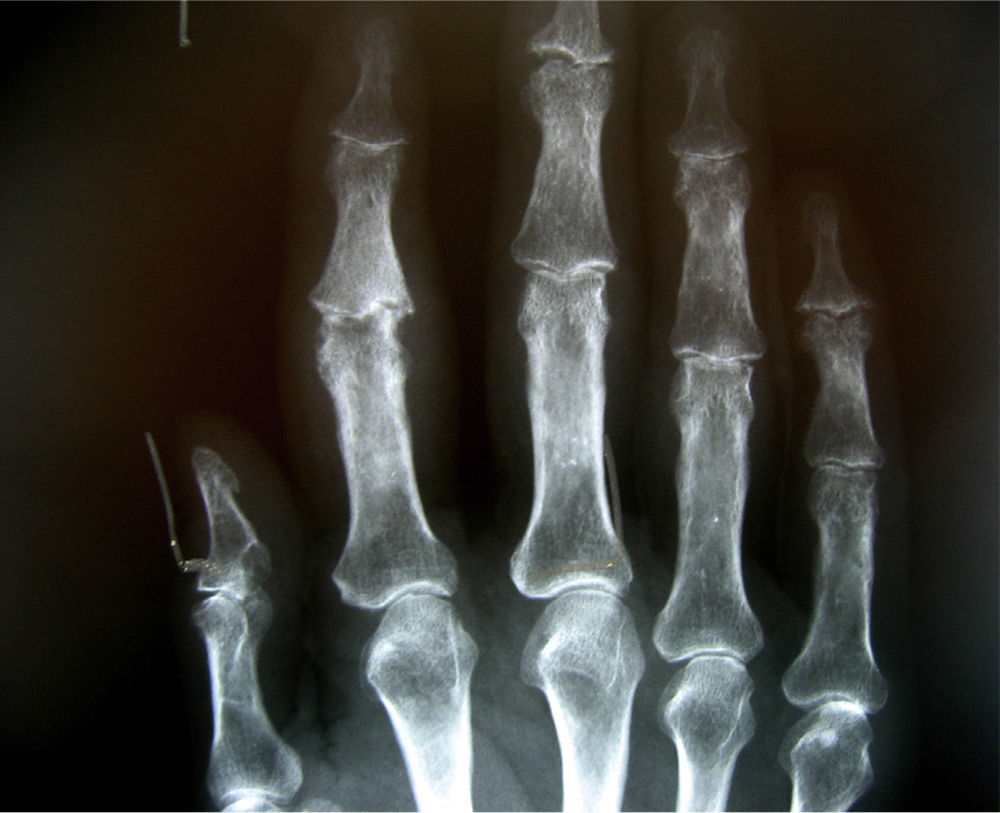

The mean follow-up period was 29 months. The indications for surgery included pain with joint destruction and reduction of joint balance. The mean age was 56 years. Out of the total, 10 patients were female and 7 were male. The preoperative diagnosis was of primary osteoarthritis (PO) in 8 cases, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in 4, post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTO) in 3 and psoriatic arthritis (PA) in 2 cases. The operated fingers were the middle in 11 cases, the index in 6 and the ring finger in 5 cases. All cases were distributed by approach, type of pathology and number of arthroplasties as follows: dorsal approach 7 PO, 3 RA, 2 PTO and 2 PA, volar approach 4 PO, 2 RA, 1 PTO and 1 PA. The implant used in all cases was the Avanta® model (Avanta Orthopedics, San Diego, CA, USA). In the past, the dorsal approach was the usual technique to conduct PIP arthroplasties at our unit. Subsequently, we became aware of the extension deficit generated by such arthroplasties and decided to carry them out through a volar approach. At present, all PIP interventions conducted at our unit are performed through a volar approach. We decided to assess the functional results obtained with the last 8 PIP arthroplasties conducted through a volar approach with a minimum representative follow-up and compare them with those with a comparable minimum representative follow-up performed in the past through a dorsal approach. Although patients were selected consecutively over time and the volar approach group was intervened more recently, we believe that the learning curve for the volar approach makes this group comparable with the dorsal approach group, which includes patients intervened at a time when less experience had been accumulated. The preoperative clinical assessment included the pain magnitude and the range of movement. The assessment of pain was based on a visual analog scale (VAS), from 0 (no pain) to 10 (intense pain). The mean score on the preoperative VAS was 6 (range: 4–8). During the visit prior to the intervention, we measured the range of movement with a goniometer. We calculated a mean preoperative range of movement for the 22 fingers, with a value of −15°/60°, with the first value representing active extension and the second active flexion. We used a mean value because the joint movement range of the 22 fingers had no significant preoperative dispersions, thus representing a homogeneous sample in this respect. During the last follow-up visit we assessed the overall satisfaction of patients as a dichotomous variable of “satisfied” or “not satisfied”. The VAS and range of movement were recorded and compared with preoperative values. The radiographic assessment consisted of posteroanterior (PA) (Fig. 1), lateral and oblique projections of the fingers. We assessed the presence or absence of peri-implant radiolucency, para-articular ossification, breakage or not of the implant and angular deviations.

Surgical techniqueAll patients were intervened with locoregional anesthesia (axillary) on an outpatient basis. We applied antibiotic prophylaxis through the administration of 1g of cefazolin 30min before the intervention or 1g of vancomycin 1h before the intervention in patients allergic to penicillin.

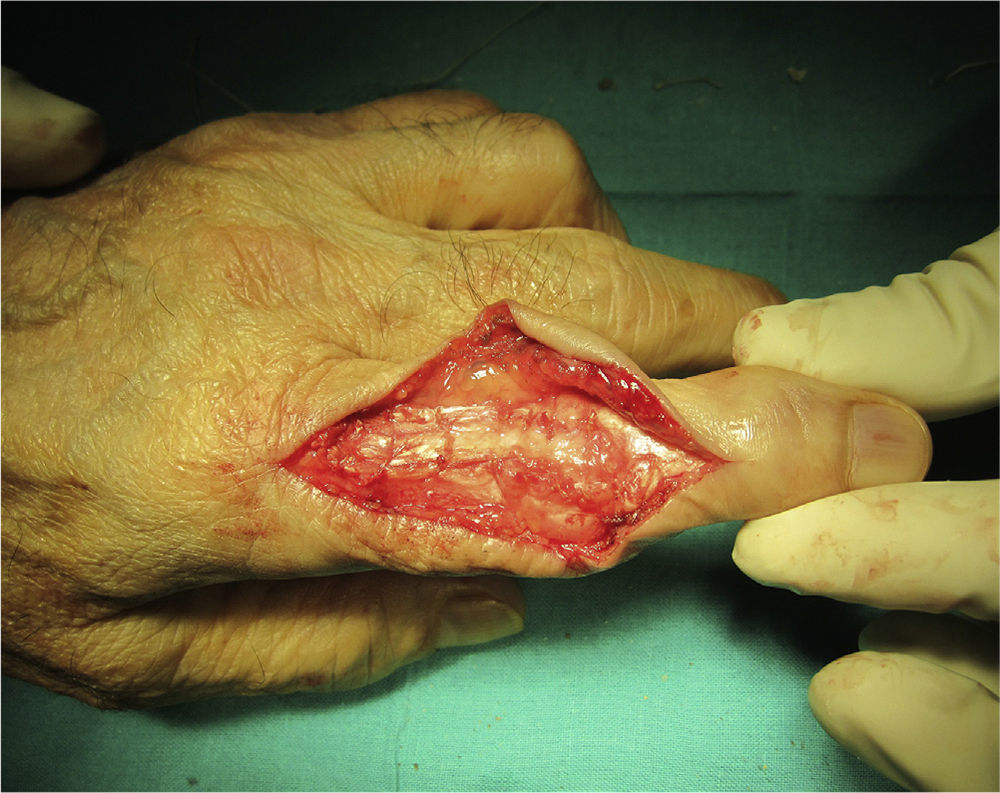

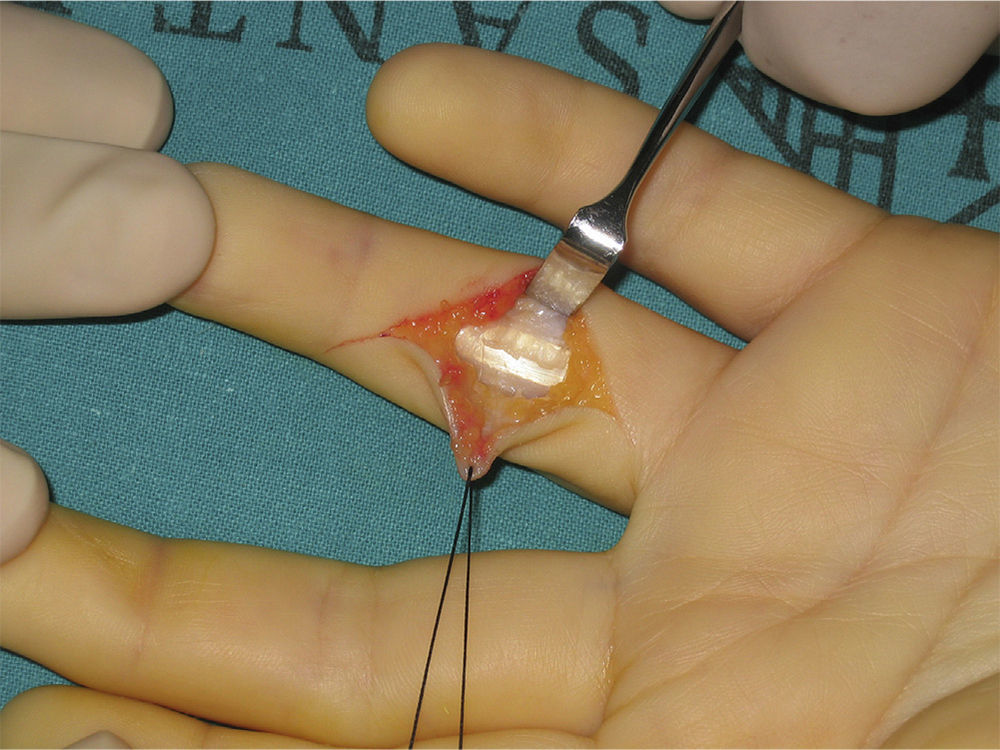

Dorsal approachPIP arthroplasties conducted through a dorsal approach were all carried out according to the Lluch modification of the technique described by Chamay.11 With the hand in a prone position and after venous expression of the limb and inflation of an ischemia cuff, a Bruner-type zig-zag incision was performed on the dorsum of the PIP. The extensor apparatus was exposed and a transverse section was made on the central band, at 2.5cm proximally to its insertion into the base of the middle phalanx. A flap of the central band was lifted distally (Fig. 2) and, after visualizing the condyles of the proximal phalanx, osteotomy and excision thereof were performed. Likewise, the joint surface of the middle phalanx was also excised and the endomedullary canal of both phalanges was prepared by progressive drilling. Along with the osteotomies, the insertions of the main collateral ligaments were sectioned, preserving those from the accessory collateral ligaments. The most adequate size and stability for the implant were determined, as well as the joint path with the test components. The final implant was then placed and the tendinous ends of the central band were sutured (Fig. 3). After closing the skin, a cast was placed with the metacarpophalangeal joints at 70° flexion and the PIP in maximum extension.

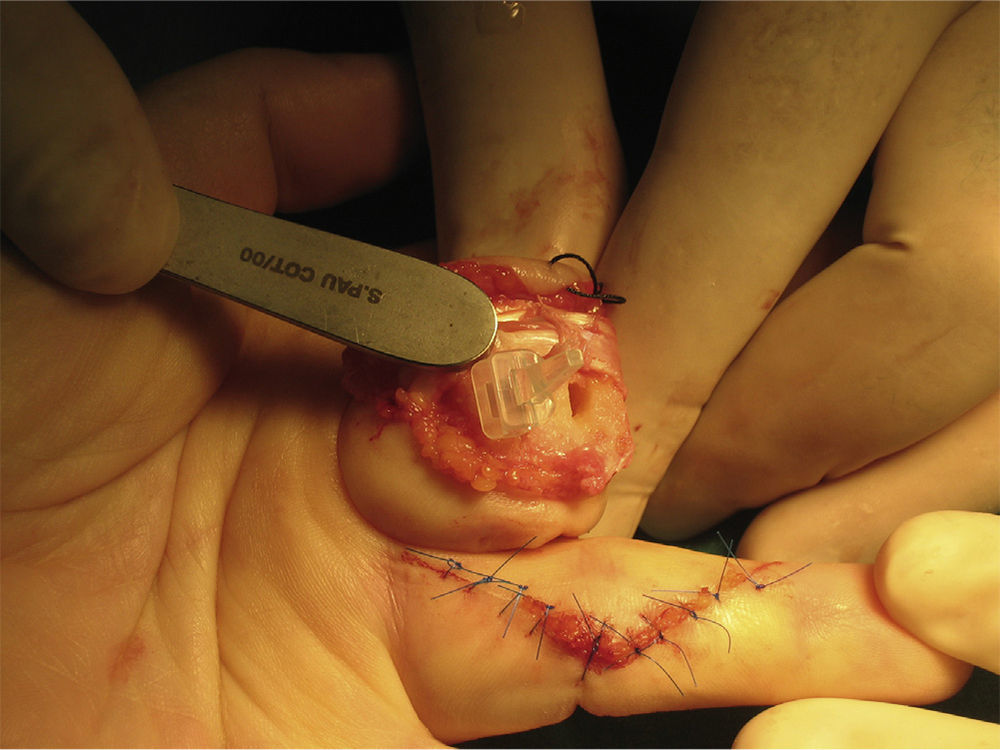

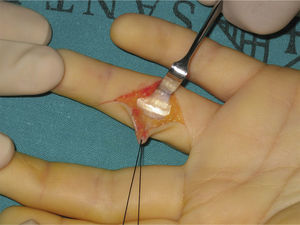

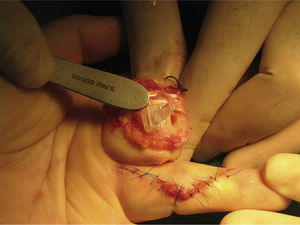

Volar approachOn a supine hand and after performing venous expression of the limb and inflation of an ischemia cuff, a Bruner-type zig-zag incision was performed on the flexion fold of the PIP (Fig. 4). A cutaneous flap was lifted and the tendon sheath between the A2 and A4 pulleys was sectioned, thus creating a flexion sheath band enabling the flexor tendons to be moved in order to access and excise the volar plate. Lastly, the PIP was extended in “gun barrel”12 to expose the joint surfaces. The condyles of the proximal phalanx and proximal joint surface of the middle phalanx were excised, along with all the osteophytic excrescences. The endomedullary canal of both phalanges was prepared by progressive drilling and the most adequate size and stability for the implant were determined, as well as the joint path with the test components, after which the final implant was placed (Fig. 5). The insertions of the main collateral and accessory ligaments were not sectioned along with the osteotomies, so the stability of the PIP was not compromised in any case. After closing the skin, a cast was placed with the metacarpophalangeal joints at 70° flexion and the PIP in maximum extension.

The case of PTO intervened by a volar approach presented a preoperative “swan neck” deformity which was corrected by reconstruction of the volar plate. This was the only case in our series in which we did not excise the volar plate.

Postoperative periodIn the dorsal approach group we carried out a section at the level of the central band of the extensor tendon and the main collateral ligaments, so the immobilization was maintained for 21 days in order to ensure their healing. Subsequently, the cast was removed and autonomous physiotherapy was started by active mobilization of the finger from the first day.

Since the palmar approach group did not undergo section of the collateral ligaments and extensor apparatus, the immobilizing cast in this group was maintained for 12 days (9 days less than in the dorsal approach group), after which autonomous physiotherapy with active mobilization was started immediately.

ResultsAt the end of the follow-up period we assessed overall satisfaction through a dichotomous choice “satisfied” or “not satisfied” and observed that 82% of patients (14/17) reported satisfaction with the result obtained. There were no differences between both groups regarding overall satisfaction (P=.163). All patients in both groups reported a notable improvement of pain symptoms. The mean preoperative VAS score was 6 and the mean postoperative was 1.2. No differences were observed between groups regarding postoperative VAS (P=.392). Mean flexion-extension went from a preoperative value of −15°/60° in both groups, to −15°/60° in the dorsal approach group and −2°/62° in the volar approach group. The comparison of postoperative joint balance between both groups revealed statistically significant differences (P<.005). Simple radiography identified 2 cases with peri-implant radiolucency, both of them with rheumatoid arthritis: 1 in the dorsal approach group and the other in the volar approach group. Para-articular ossifications were observed in 9 patients (2 in the volar approach group and 7 in the dorsal approach group). A case of PO which was intervened through a volar approach suffered bone ankylosis. Bony bridges formed between both phalanges and eventually fused them both completely. This case was not excluded from the mean joint balance in the volar approach group. One case in the dorsal approach group had to undergo arthrodesis due to implant breakage and subsequent joint instability. In this case, the dorsal adhesions and subsequent imbalance between flexion and extension forces gave rise to a swan neck deformity of the PIP prior to implant breakage.

There were no complications such as infection, postoperative angular deviations, synovitis by silicone particles and lateral instability.

DiscussionTo the best of our knowledge, there are no studies comparing the dorsal and volar proximal interphalangeal approaches in joint replacement arthroplasties. The main finding of this study was that the extension range achieved by fingers undergoing PIP replacement arthroplasty through a volar approach was greater than that achieved by cases intervened through a dorsal approach.

Regarding complications related to the approach route employed for PIP prosthesis implantation, the fact that the volar approach did not interrupt the extensor apparatus could lead it to be considered less harmful that the dorsal approach and, therefore, theoretically more suitable to achieve restoration of the mobility range.

A literature review about complications of PIP surface arthroplasties requiring revision surgery published in 2011 concluded that the majority of reinterventions were due to complications related to the extensor apparatus. Moreover, a meta-analysis reviewing 319 articles which was published in 2012 reported that the dorsal approach was clearly the most commonly employed and that the proportion of preoperative complications derived from it could reach 27.8%.13 In our series, the only reintervention which we found it necessary to perform was in a patient from the dorsal approach group, who had to undergo arthrodesis due to implant breakage. In this case, dorsal adherences and the subsequent imbalance of flexion and extension forces gave rise to a swan neck deformity of the PIP prior to implant breakage.

Regarding the joint range, many of the series published on PIP arthroplasties did not achieve an improvement of the postoperative joint range compared to the preoperative.13 A series of 70 PIP arthroplasties implanted through a dorsal approach and with a long-term follow-up reported a very discreet improvement of the joint range, with the mean postoperative value being 30° compared to a preoperative value of 26°.8 In our series, we did not observe a superior postoperative mobility range in the dorsal approach group compared to that prior to the arthroplasty. There are even some works by authors who employed the dorsal approach to implant a silicone prosthesis and reported a decrease in the range of mobility, going from a preoperative mean value of 38° to a postoperative mean of 29°.14 On the other hand, other authors have reported that the postoperative joint balance achieved in 14 out of 20 cases in their PIP series intervened through a dorsal approach was of 73.1°. Moreover, these authors also reported observing a mean joint balance of 19.6° in the 6 remaining cases, even after conducting tenolysis or manipulation under anesthesia.9 We believe that since the dorsal approach and subsequent immobilization often required for the scarring of structures affect the extensor mechanism, this conditions the development of adherences and rigidities in a non-negligible percentage of PIP intervened through this approach. Regarding the volar approach, the series are smaller and with shorter follow-up periods. A series of 6 PIP arthroplasties implanted through a volar approach published in 2011 described an increase of the total range of movement in all patients, going from a preoperative mean of 33° to a postoperative mean of 60°.15 Regardless of the approach employed, we believe that a significant improvement of mobility should not be expected in patients in whom the preoperative joint range is almost zero, among other reasons because the presence of adhesions of the flexor tendons in the digital canal is very likely, due to the fact that their pathway has been abolished for an extended period.

Regarding the type of implant used in all cases in our series (Avanta®, Avanta Orthopedics, San Diego, CA, USA), we believe that one of the advantages offered by silicone arthroplasties is that their implantation is technically less complex, and another is that they cannot become loosened, which can be a problem with other types of implants. In fact, a prospective and randomized review of surface implants with 2 components (both pyrolytic carbon and titanium-polyethylene) and silicone implants, concluded that surface implants with 2 components presented a much higher rate of postoperative complications than silicone implants, with the rate of failures among the group of pyrolytic carbon implants being 39%, that of titanium-polyethylene being 27% and that of silicone implants 11%.16 Moreover, the functional results published in series of patients undergoing PIP surgery with silicone implants are very similar to those described with the use of more modern pyrolytic carbon surface-covering implants.17

On the other hand, from a technical standpoint, the implantation of a silicone PIP prosthesis involves performing 2 parallel bone sections which are perpendicular to the middle axis of the proximal and middle phalanges, which can be performed both through a volar and a dorsal approach. It is also worth mentioning that the instrumentation employed to section and place the PIP implants with 2 components has been exclusively conceived and designed for the dorsal approach route. Preparation of the proximal phalanx prior to the placement of a PIP implant with 2 components involves an oblique osteotomy which can only be performed through a dorsal approach. This fact means that the volar approach route can only be considered for the placement of silicone implants.

We believe that the volar approach is much less aggressive than the dorsal, so we currently employ the volar approach systematically. The fact that PIP arthroplasties implanted through a dorsal approach entail immobilization of the PIP during the period required by the main collateral ligament and the extensor tendon to scar, means that physiotherapy with active mobilization will be started later. In our series, we recognize that the fact that the immobilization time of the group undergoing a dorsal approach was longer may have been relevant in the result of the postoperative joint balance.

Our study has the limitation of consisting of a retrospective review in which we selected patients consecutively over time. Patients in the dorsal approach group were intervened during an earlier period compared to those in the volar approach group, and both groups were intervened during periods in which we had different ways of approaching the pathology.

The results of our study provide evidence allowing us to conclude that PIP replacement arthroplasties conducted through a volar approach route achieve a greater range of extension than those carried out through a dorsal approach.

Further prospective and randomized studies conducted on a sample of patients with homogenous pathologies will be required in order to confirm the validity of the results of this work.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that this work does not reflect any patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that this work does not reflect any patient data.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Natera L, Moya-Gómez E, Lamas-Gómez C, Proubasta I. Artroplastia de la articulación interfalángica proximal: comparación entre el abordaje palmar y dorsal. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2014;58:303–308.