The aim of this study was to evaluate the long term outcome of surgical treatment for displaced ankle fractures in patients over 65 years of age, and determine the influence of age and comorbidity in the occurrence of complications.

Material and methodRetrospective descriptive study on 40 patients, with a mean age of 72.7 years (range: 65–88), who underwent open reduction and internal fixation for the treatment of a displaced ankle fracture. The patients were clinically evaluated according to the AOFAS criteria (functional outcome). Data collection also included the presence of comorbidities, radiographic evaluation, the occurrence of postoperative complications, and a questionnaire on satisfaction with treatment received. The mean follow-up was 5.73 years.

ResultsAt the end of the follow-up, according to the AOFAS criteria, excellent/good results were obtained in 75% of the patients (n=30), with 38 patients referring to be quite/very happy with the result. Wound skin problems and metal work migration were the most common post-operative complications. No statistically significant relationship was found between increased age or a high number of comorbidities and an increased occurrence of postoperative complications (p>.05). Only 3 patients needed postoperative rehabilitation, and 95% of the patients (n=38) returned to their activities of normal daily living.

ConclusionsSurgical treatment of displaced ankle fractures in the elderly patient facilitates the early resumption of the activities of daily living.

Evaluar el resultado a largo plazo del tratamiento quirúrgico mediante reducción abierta y fijación interna de las fracturas de tobillo en los mayores de 65 años, y determinar la influencia de la edad y enfermedades previas en la aparición de complicaciones.

Material y métodoEstudio descriptivo retrospectivo sobre 40 pacientes, con una edad media de 72,7 años (rango: 65-88) intervenidos mediante reducción abierta y fijación interna por presentar fractura de tobillo desplazada. Los pacientes fueron valorados según criterios de la AOFAS, que valora el resultado funcional del tratamiento. También fueron evaluadas la presencia de comorbilidades, parámetros radiográficos, complicaciones y valoración subjetiva del paciente. Seguimiento medio de 5,73 años.

ResultadosAl final del seguimiento, según criterios de la AOFAS se obtuvieron excelentes/buenos resultados en el 75% de los pacientes (n=30); 38 pacientes refirieron estar bastante/muy contentos con el resultado. Las complicaciones más frecuentes fueron la migración del material de osteosíntesis y los problemas cutáneos de la herida. No se pudo demostrar relación estadísticamente significativa entre una mayor edad o un mayor número de enfermedades previas y una mayor frecuencia en la aparición de complicaciones (p>0,05). Únicamente 3 pacientes necesitaron tratamiento de rehabilitación postoperatoria; el 95% de los pacientes (n=38) refirieron haber regresado a sus actividades de vida diaria con normalidad.

ConclusionesEl tratamiento quirúrgico de las fracturas desplazadas de tobillo en el paciente anciano facilita la pronta reanudación de las actividades de la vida diaria.

Nivel de evidencia IV.

Ankle fractures are amongst the most common bone injuries of the lower limb1,2 and are a major source of morbidity.3 It is estimated the incidence of ankle fracture is 184 per 100,000 inhabitants a year, of which approximately 20% to 30% occur in the elderly.4

Recent epidemiological studies have demonstrated a significant increase in the number and severity of ankle fractures in people aged over 65,3,5–7 and therefore these fractures can be considered to have a second peak in incidence in patients aged between 65 and 84, and this incidence peak is even higher in women. This increase in incidence could be due to higher life expectancy, but is also certainly due to the increased activity of people aged over 65.8

Despite its increase in incidence, medical literature has not evaluated ankle fractures in the elderly in as much depth as those of the hip or wrist,8 and therefore there is still debate as to the ideal treatment.3,8,9

In the last 30 years, the treatment of unstable ankle fractures has become predominantly surgical, with several studies which demonstrate the benefits of this type of treatment.10–16 However, several authors recommend conservative treatment for ankle fractures in the elderly because of the poor surgical results obtained in relation to poor bone quality due to the presence of osteoporosis, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease and problems with the skin and healing.3,8,9,12,17 And therefore in general, ankle fractures in this group of patients are still treated conservatively.12

Conservative treatment of a poorly reduced joint can result in bone-healing defects,11 the need for prolonged immobilisation,3 post traumatic arthrosis, deformity, reduced joint mobility range, chronic pain and functional limitation.9,10 And in elderly patients, prolonged immobilisation and discharge can result in a permanent change in their physical and systemic status and walking ability. Therefore the study of ankle fractures in the elderly merits special care due to their frequent presentation, severity and variability, and the repercussions of treatment on the patient's health, functionality and independence.

The objective of our study was to evaluate the long-term result of surgical treatment by open reduction and internal fixation of unstable ankle fractures in people aged over 65, and to determine the influence of age or the presence of prior disease on the appearance of surgical complications.

Patients and methodologyAn observational, descriptive and retrospective study performed on consecutive patients over the age of 65, operated between January and December 2008 due to displaced ankle fracture.

The patients included had undergone open reduction and internal fixation after presenting with displaced and unstable ankle fracture on entry, or due to failure of treatment by closed method due to a subsequent displacement of fragments during the first weeks. Patients aged und 65 at the time of surgery, non ambulant patients, patients with tibial pilon fractures, concomitant lower limb fractures, patients with previous or accompanying injuries or surgery which might affect the functionality of the ankle, patients who underwent surgery for sequelae, pathological fractures and fractures which could not be located were excluded from the study.

Of the 66 patients initially included in the study, 5 died, 6 were not located with the available personal data, and 15 patients either refused to or it was not possible for them to take part in the study. Eventually 40 patients were located and met the inclusion criteria. Data on filiation, gender, age, anthropometric traits, medical and surgical history, the mechanism and cause of the injury and information on the surgical intervention, appearance of complications and postoperative recovery were collected by preparing a standardised questionnaire. All the fractures were classified using the Dannis–Weber system18 by evaluation of preoperative radiographs.

All the patients were assessed according to the criteria of the clinical rating system of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society,19 which assesses the functional result of treatment. With a maximum of 100 points, this scale assesses the alignment of the foot (0–10 points), pain (0–40 points), and degree of functionality (0–50 points), the result is considered excellent if the score is above 85, good between 70 and 84, fair between 50 and 69, and poor if the score is lower than 49 points. The patients’ subjective satisfaction with the treatment received was also obtained (very satisfied, quite satisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, very dissatisfied), whether they had difficulties in carrying out their daily activities due to their fracture, and whether they would undergo the same treatment again.

All the patients with displaced fractures urgently underwent closed manipulation of the fracture and immobilisation by castor splint under mild sedation or preventive analgesia. Open reduction and internal fixation were carried out if the initial reduction was unsatisfactory, or if reduction and maintenance of the fracture was not possible after immobilisation. Reduction was judged satisfactory in displacements of the malleoli (including in the case of fragments of >25% of the posterior malleolus) or talus.

With regard to surgical technique, in all cases treatment was dictated by the specialist in charge on the day that the patient was admitted. Open reduction and internal fixation were only performed on patients who were capable of walking. After surgery, all the patients were immobilised using a posterior splint or plaster cast and were not allowed to weight bear on the affected limb for 6–8 weeks. After the period of immobilisation individual rehabilitation exercises were given at home and patients who found rehabilitation difficult at home were assessed and treated by the Rehabilitation Service of our hospital.

The results were collected by creating an Excel database and analysed statistically by SPSS software, a difference between groups with a P-value lower than 0.05 was established as significant.

ResultsOf the 40 patients included in the study, 8 were male (20%) and 32 female (80%) with a mean age of 72.7 (range: 65–88). In 27 cases the injured ankle was the right ankle (67.5%) and the left in the remaining 13 (32.5%). Mean follow-up at the time of review was 5.73 years (range 5–6 years). In terms of the mechanism of injury, 55.5% of the ankle fractures were due a fall in the street, 18.5% due to a road accident, 14.8% due to a fall in the home and 11.1% after a fall in the bathroom. There were different degrees of being able to walk preoperatively, but our entire patient cohort was able to walk before the fracture.

The most common ankle fracture was bimalleolar in 77.5% (n=31) of the patients, followed by trimalleolar fracture in 15% (n=6), isolated fracture of the peroneal malleolus in 7.5% (n=3), and none of the patients presented an isolated fracture of the tibial malleolus. According to the Dannis–Weber classification, 77.5% (n=31) of the fractures of the fibula were at the level of the syndesmosis (Weber type B); 17.5% (n=7) were supra-syndesmotic (Weber type C); 5% (n=2) infra-syndesmotic (Weber type A). Twenty-five point eight percent of the type B Weber (n=8) fractures were associated with dislocation of the ankle. Ninety five percent of the patients presented a closed fracture and 5% (n=2) presented an open fracture (type II and IIIA, according to Gustilo's classification, respectively).

Ninety-two point five percent of the patients underwent fixation of both medial and lateral malleoli, and 7.5% underwent isolated fixation of the lateral malleolus. The method most used for synthesis of the lateral malleolus was closed reduction plus percutaneous fixation with Rush intramedullary nails or Kirschner wires in 60% (n=24) of cases (Fig. 1); in 22.5% of the patients (n=9) a combination of Kirschner wires and cerclage wire were used as the internal fixation system, and one-third tubular locking plate was used±interfragmentary screws in 17.5% (n=7).

The method most used for synthesis of the medial malleolus was also closed reduction plus percutaneous fixation with Rush intramedullary nails or Kirschner wires in 70.2% (n=26); using interfragmetary screw/s (±Kirschner wire or Rush nail) in 27.1% (n=10) (Fig. 2); and cerclage wire was used in 2.7% (n=1) of the patients.

67 year-old patient. (A) Displaced trimalleolar fracture. (B) Postoperative radiography after treatment by open reduction and synthesis with interfragmentary screws and Kirschner wires. (C) Radiography at the end of follow-up with preservation of the reduction and radiographic signs of joint degeneration due to arthrosis.

It was possible to observe repair of the deltoid ligament in 37.5% of the cases (n=15), and a supra-syndesmotic screw was used in 15% of the ankle fractures (n=6) which was removed after a mean of 4.7 weeks (range: 4–7 weeks) (Fig. 3). The mean admission time was 6.3 days (range: 2–18 days). The patients who were less able to collaborate in the active exercises, 7.5% of patients (n=3), were referred to Rehabilitation to regain their ability to walk and range of mobility.

71 year-old patient. (A) Displaced bimalleolar fracture. (B) Postoperative radiography after treatment by open reduction and synthesis with screwed plate, Kirschner wires and supra-syndesmotic screw. (C) Radiography at the end of follow-up. Despite satisfactory initial reduction with joint congruence, the presence of degenerative signs in the form of subchondral sclerosis can be seen. The patient is asymptomatic.

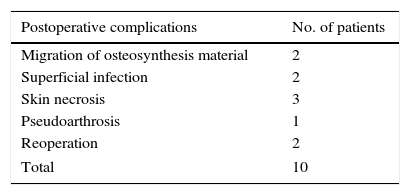

With regard to post-surgical complications, in this study, 10 patients presented a postoperative complication (25%), and although it could be considered minor, this information should be taken into account. Five patients (12.5%) suffered problems with skin infection or healing: 2 patients presented a wound surface infection and 3 skin necrosis, which were satisfactorily treated by lavage and debridement of the wound and antibiotherapy, without the need to remove the osteosynthesis material. Two patients (5%) presented protrusion of the osteosynthesis material and early removal of part of the osteosynthesis material was necessary, and one patient required a second operation to place a supra-syndesmotic screw. None of the patients presented deep vein thrombosis, systemic infection, or cardiorespiratory problems, and no patient died during hospital admission or subsequently as a consequence of the surgical treatment of their fracture. One of the patients was diagnosed with pseudoarthrosis of the fracture (2.5%), but the patient refused a second operation as they suffered few symptoms and little discomfort, however, another patient had to be reoperated to perform an arthrodesis for incapacitating pain (Table 1). After stratifying the patients by age, no statistically significant relationship could be identified between greater age and greater frequency in the appearance of complications (P>0.05). However, despite the few patients who presented an open fracture in this series, both cases were associated with the appearance of skin problems.

Postoperative complications.

| Postoperative complications | No. of patients |

|---|---|

| Migration of osteosynthesis material | 2 |

| Superficial infection | 2 |

| Skin necrosis | 3 |

| Pseudoarthrosis | 1 |

| Reoperation | 2 |

| Total | 10 |

Some migration of the osteosynthesis material could be seen in 2 of the patients; two patients presented surface infection of the wound and 3 had skin necrosis; one of the patients was diagnosed with pseudoarthrosis; one patient required a second operation to place a supra-syndesmotic screw; one patient had to be reoperated to perform arthrodesis due to incapacitating pain. None of the patients presented deep vein thrombosis, systemic infection, or cardio-respiratory problems, and no patients died during or after admission to hospital as a consequence of the surgical treatment of their fracture.

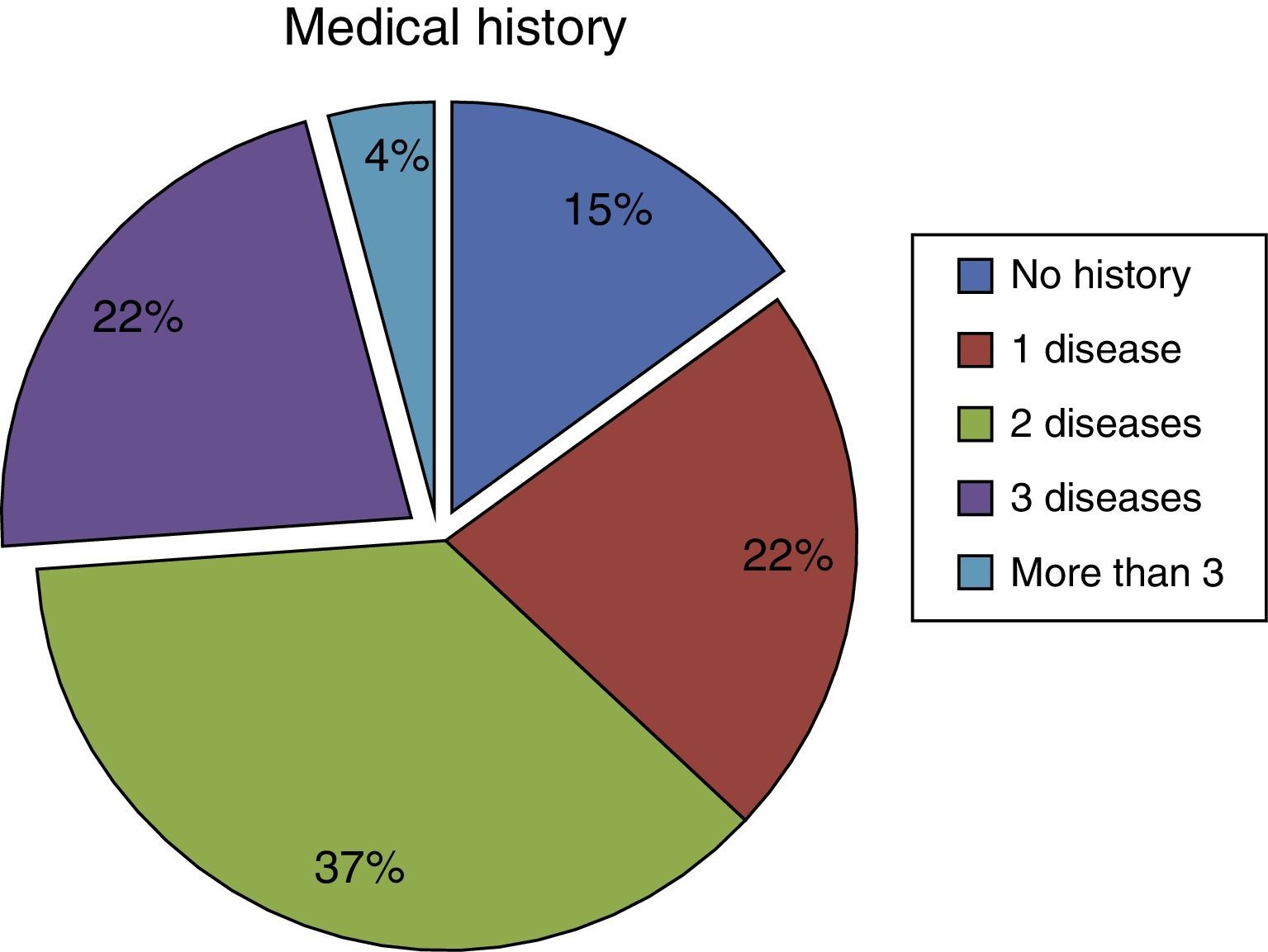

Eighty-seven point five percent (n=35) of the patients in this study presented some previous medical problem. Twenty-two point five percent (n=9) of the patients presented a disease of one system, 37.5% (n=15) had disease of two systems, 22.5% (n=9) of three systems, and 5% (n=2) of more than three systems (Fig. 4). However, it was not possible to demonstrate a statistically significant relationship between a greater number of previous diseases and the appearance of post-surgical complications (P>0.05).

22.5% (n=9) of patients presented a disease of one system; 37.5% (n=15) had disease of two systems; 22.5% (n=9) of three systems; 5% (n=2) of more than three systems. It was not possible to demonstrate an association between a greater number of previous diseases and the appearance of postoperative complications (p>0.05).

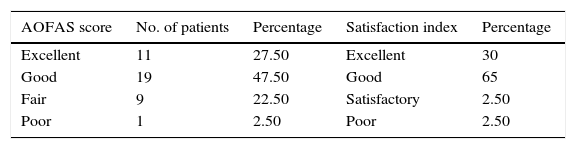

At the end of follow-up according to the functional evaluation using the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society's clinical scale,19 excellent/good results were obtained after surgical treatment of the fracture in 75% of the patients (n=30), fair results were obtained in 22.5% of the patients (n=9) and a poor result in 2.5% (n=1) of the patients (Table 2).

Results.

| AOFAS score | No. of patients | Percentage | Satisfaction index | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | 11 | 27.50 | Excellent | 30 |

| Good | 19 | 47.50 | Good | 65 |

| Fair | 9 | 22.50 | Satisfactory | 2.50 |

| Poor | 1 | 2.50 | Poor | 2.50 |

According to the AOFAS excellent/good results were obtained in 75% of the patients (n=30); fair results in 22.5% of the patients (n=9); and poor in 2.5% (n=1). Thirty eight patients reported that they were quite satisfied or very satisfied with the final result; one patient was neither satisfied nor dissatisfied; and one patient was very dissatisfied. Ninety-five percent of the patients (n=38) reported that they had resumed their normal daily activities. Ninety-seven point five % of the patients (n=39) would undergo the same surgical intervention again.

Ninety-five percent of the patients (n=38) reported having regained their preoperative state of mobility and were able to resume their normal daily activities. Only two of the patients who had been independent in daily life became dependent on care at home.

Within the levels of overall satisfaction, 38 patients reported that they were quite satisfied or very satisfied with the final surgical treatment of their fracture; one patient was neither satisfied nor dissatisfied; and similarly another patient was very dissatisfied. When asked if they would undergo the same surgical intervention, 97.5% of the patients (n=39) responded in the affirmative; only the patient on whom it was necessary to perform an arthrodesis reported that given the result obtained and under the same circumstances, they would not undergo the operation again.

DiscussionThe immediate objective of the treatment of displaced ankle fractures in elderly patients is to provide a pain free joint in order to enable the patient to resume their daily activities rapidly and prevent deterioration of their general condition due to prolonged bedrest.8

In younger patients it is important to prevent the potential risk of arthrosis after an ankle fracture. However, in elderly patients, early functional rehabilitation might be more important than anatomical reduction, as the development of post-traumatic arthrosis can take years to appear, during which time patients of advanced age can regain their functional status.8 However, degenerative changes can be seen after 2–3 years.

Despite the increased incidence, treatment of these fractures in the elderly remains controversial.3,8,9 The best possible treatment modality and its implications have not been assessed in medical literature in as much depth as those of hip or wrist fractures,8 and there is great variability in the proportion of ankle fractures treated surgically, this proportion of surgical treatment varies from 14% to 72%.20

Salai et al.8 published superior results in elderly patients with non-surgical treatment, confirming that in many cases conservative treatment can result in a better functional result. However, Anand and Klenerman21 demonstrated that open reduction and internal fixation in elderly patients maintain better anatomical congruence and produce a better result than non-surgical treatment. According to Pagliaro et al.14 the result of surgical treatment of ankle fractures in the elderly is comparable with that of the general population. Elderly patients can tolerate a less precise reduction better; however, the best results have been obtained after anatomical reduction.22

The presence of osteoporosis will often limit achieving stable fixation, however some fractures are highly unstable which makes conservative treatment inadvisable.9,23 In this study, bi/trimalleolar fractures were 92.5% of the operated fractures. These results are not surprising, as bi/trimalleolar fractions are unstable injuries which are best treated by internal fixation. The treatment of isolated fractures of the medial or lateral malleoli attracts more controversy.6,20

The incidence of problems in bone consolidation in this study (5%) is in line with those published by Leach and Fordyce (7%), Srinivasan and Moran (5%), and Vioreanu et al. (1.4%), with similar incidences after internal fixation.10,12,13 In the presence of osteoporosis, failure of internal fixation is more common due to reduced mechanical resistance of the bone because of implant failure. In order to prevent greater bone loss, less rigid implants which reduce the appearance of stress shielding, such as wire cerclages and intramedullary implants (Rush, Kirschner, Knowles, Steinman), might be a better option than synthesis with a plate.22,24 Lee et al.15 performed a retrospective study with patients >50 presenting with ankle fractures (AO type B2), and divided them into two comparable groups according to the type of synthesis used: synthesis with plate or Knowles intramedullary nail. They achieved a better hospital stay duration, better surgery time, less need for analgesia and fewer postoperative complications associated with the implant in the group which was synthesised with Knowles intramedullary nail. Pritchett25 obtained similar results in favour of Rush intramedullary nails compared to osteosynthesis with a plate in elderly patients. However, treatment with intramedullary systems has poorer control of rotation over fragments, and therefore should perhaps be reserved as a second option for patients at high risk of skin complications. Experience with the use of plates using minimally invasive techniques26 has also been published recently, osteosynthesis with cemented screws,27 retrograde calcaneotalotibial expandable arthrodesis nails,28 and retrograde fibula locking nails29 as alternatives to traditional osteosynthesis of ankle fractures in the elderly.

In our series, with 60% of the syntheses undertaken using percutaneous methods, 12.5% of the patients presented problems with skin infection or healing (n=5), in line with the results of series published by Srinivasan et al. (11%) and by Leach and Fordyce (7%) who also used osteosynthesis methods with a plate or percutaneous intramedullary synthesis.12,13 The two patients who presented an open fracture (Gustilo type II and IIIA respectively) subsequently developed a wound infection. The appearance of skin and healing problems (infection, dehiscence and necrosis), was associated with the presence of open fractures, diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease.4,13,14

The presence of diabetes mellitus was associated with an increased risk of post-surgical complications in the treatment of ankle fractures in the elderly. McCormack and Leith,30 published a 36.6% incidence of complications in diabetic patients including amputation and death. Flynn et al.31 quantified that the risk of complications appearing in diabetic patients was four times greater than in the general population.

Patients over the age of 65 often have multiple medical problems, which might increase the probability of peri-operative complications.4 Therefore, if the risk of surgery in this population is greater, it is necessary to understand potential benefit in order to help the patient and the surgeon in decision-making.3 However in our series we did not find an association between a greater number of previous diseases and the appearance of postoperative complications.

The limitations of the study should be recognised. All the patients initially presented joint incongruency which was an indication for surgery in all cases. Therefore the supposition that with the presence of significant displacement the results would be better after surgery is an inherent bias. We did not perform a comparative study with another technique or method of treatment. The predominant surgical treatment in this series is intramedullary fixation (60%): a method which is not recommended as routine treatment and to which up to 50% of the complications obtained can be attributed. As with all retrospective studies, the selection criteria might not be reproducible and our system does not enable us to identify the number of ankle fractures treated conservatively in this same period of time. Therefore it might be that the fractures that were operated were the most complex fractures. Other limitations to be mentioned are the size of the sample with a high loss of patients and the fact that a comparative study between treatment techniques or methods was not undertaken; the study only presents review data of the results with a certain surgical treatment at mid to long term. Finally, the results were not stratified with regard to the type of underlying disease (such as diabetes mellitus, vascular insufficiency.) but rather with regard to the number of diseases.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that for this research study no experiments have been undertaken on human beings or animals.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have not received any financial help in order to undertake this study. Neither have they signed any agreement for which they will receive any benefits or fees on the part of any commercial entity. Furthermore, no commercial entity has paid or will pay foundations, educational institutions or other non profit-making organisations with which the authors are affiliated.

Please cite this article as: Tomé-Bermejo F, Santacruz Arévalo A, Ruiz Micó N. Resultado a los cinco años del tratamiento quirúrgico de las fracturas desplazadas de tobillo en los pacientes mayores de 65 años. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:99–105.