Since the development of locking plates, calcaneal fractures have been considered ideal for this type of fixation, due to the need to maintain the height of the subastragaline joint after depression fractures in a location where bone quality tends to be poor. However, there are no comparative studies that support the theoretical superiority of these plates over conventional plates. The aim of this study was to compare the results of intraarticular calcaneal fractures treated using locking plates versus conventional plates in terms of radiological reduction, complications and number of reinterventions.

Material and methodsWe designed a comparative study of calcaneal fractures operated in our centre using the “L” approach. Two groups were established: Group B, comprising 15 patients operated between 2010 and 2015 with calcaneal locking plates and Group A, comprising a stratified random sample of 23 patients taken from a historical cohort of 90 patients operated in our centre between 1997 and 2007 using conventional calcaneal plates. Demographic data were recorded (age, sex, diabetes mellitus, smoking) and data relating to the fracture (type of fracture according to Sander’s classification system, complications, presurgical delay). To evaluate loss of reduction, varus angulation of the calcaneus (measured from the axial view), Böhler’s angle and Gissane’s angle were assessed radiographically. These angles were measured preoperatively, immediately postoperatively, and at the end of follow-up. Finally, we recorded complications and the number of reinterventions.

ResultsThere were no differences in terms of age, sex or fracture type between the two groups. There was greater loss of varus angulation in group A, .6° versus .41°, and there was greater reduction in Böhler’s angle in group A, 3.79° versus 2.6°, while Gissane’s angle decreased more in Group B, 4.13° versus 2.52°. There were no significant differences in the proportion of complications and reinterventions between the two groups.

ConclusionIn our study we observed no significant differences between the two groups in terms of radiological reduction, complications or number of reinterventions. However, we did observe a greater loss of reduction of Böhler’s angle in the patients who were operated using conventional plates.

Desde el desarrollo de las placas bloqueadas, las fracturas de calcáneo han sido consideradas como ideales para este tipo de fijación, debido a la necesidad de mantener la altura de la articulación subastragalina tras las fracturas hundimiento, en una localización donde la calidad ósea suele ser pobre. Sin embargo, no contamos con estudios comparativos que apoyen la superioridad teórica de estas placas frente a las convencionales. El objetivo de este estudio es comparar los resultados de las fracturas intraarticulares de calcáneo tratadas mediante placas bloqueadas versus convencionales, en cuanto a pérdida de reducción radiológica, complicaciones y número de reintervenciones.

Material y métodosDiseñamos un estudio comparativo de fracturas de calcáneo intervenidas en nuestro centro mediante abordaje en "L". Se establecieron 2 grupos: Grupo B: formado por 15 pacientes intervenidos entre los años 2010 y 2015 con placas bloqueadas de calcáneo y Grupo A: formado por una muestra aleatoria estratificada de 23 pacientes extraídos de una cohorte histórica de 90 pacientes intervenidos en nuestro centro entre 1997 y 2007 con placas convencionales de calcáneo. Se registraron datos demográficos (edad, sexo, diabetes mellitus, tabaquismo) y datos relacionados con la fractura (tipo de fractura según clasificación de Sanders, complicaciones, demora pre-quirúrgica). Para evaluar la pérdida de reducción se evaluaron radiográficamente, la angulación en varo del calcáneo (medida en la proyección axial), el ángulo de Böhler y el ángulo de Gissane. Dichos ángulos se midieron preoperatoriamente, en el postoperatorio inmediato y al final del seguimiento. Finalmente, se registraron las complicaciones y el número de reintervenciones.

ResultadosNo hubo diferencias en cuanto a la edad, sexo y tipo de fractura entre ambos grupos. Hubo mayor pérdida de la angulación en varo en el grupo A, 0,6º vs 0,41º, también hubo mayor disminución del ángulo de Böhler en el grupo A, 3,79º vs 2,6º, mientras el ángulo de Gissane disminuyó más en el Grupo B, 4,13º vs 2,52º. No hubo diferencias significativas en la proporción de complicaciones y reintervenciones entre ambos grupos.

ConclusiónEn nuestro estudio no se observan diferencias significativas entre ambos grupos en cuanto a la pérdida de reducción radiológica, complicaciones y el número de reintervenciones. Sin embargo, observamos mayor pérdida de reducción en el ángulo de Böhler en los pacientes intervenidos con placas convencionales.

The calcaneus is the bone most commonly affected by a trauma in the tarsus. It constitutes 2% of all fractures and in approximately 75% of cases a component of a joint is involved.1

The use of locking plates is particularly useful in joint fractures with severe instability, poor bone quality or the impossibility of bicortical fixation.2 In joint fractures in other locations such as the knee, locking plates have demonstrated good clinical results.3

The biomechanical properties of locking plates and non locking plates in the calcaneus in cadavers and saw-bones have been described in the literature.4,5 However not enough evidence supports the superiority of the locking plates in calcaneus fractures in clinical practice.

The aim of this study is to compare the results of intraarticular calcaneal fractures treated using locking plates versus conventional plates, in terms of radiological reduction, complications and reinterventions.

Material and methodsWe designed a comparative study of calcaneal fractures operated on in our centre using the “L” approach. Two groups were established:

- 1

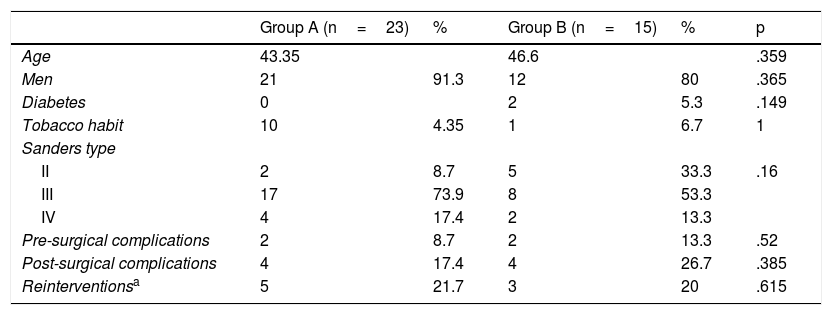

Group B: comprising 15 patients operated on between 2010 and 2015 with calcaneal locking plates (model LCP for calcaneus, Depuy Synthes®, Oberdorf, Switzerland).

- 2

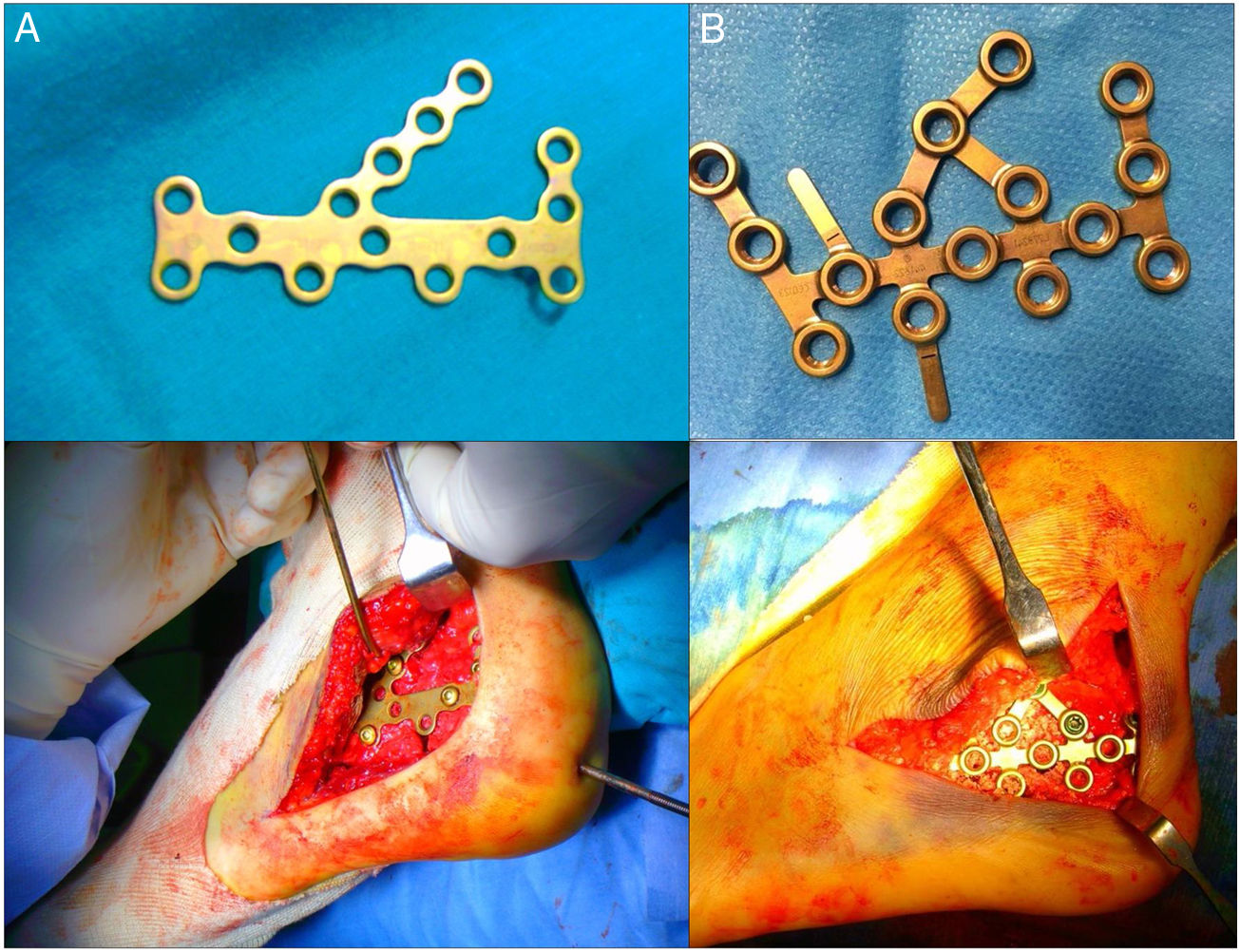

Group A: comprising a stratified random sample of 23 patients taken from a historical cohort of 90 patients operated on in our centre between 1997 and 2007 with conventional cancaneal plates (classical model of calcaneal plate AO with Synthes® non locking screws, Oberdorf, Switzerland) (Fig. 1).

Demographic data were recorded (age, sex, diabetes mellitus and smoking habit) and data relating to the fracture (type of fracture according to the Sanders6 classification system, complications, presurgical delay). To evaluate loss of reduction varus angulation of the calcaneus (measured from the axial view) Böhler’s angle and Gissane’s angle were assessed radiographically. These angles were measured preoperatively, immediately postoperatively and at the end of follow-up. Finally we recorded complications and the number of reinterventions.

Indications for surgery included joint fractures with involvement of the posterior facet, fracture of the anterior process with involvement of over 25% of the calcaneal-cuboid joint, displaced fracture of the posterior tuberosity or fracture-dislocation. Patients treated with percutaneous fixation osteosynthesis with a different type of plate, open fractures and with conservative type treatments were excluded.

The fractures were evaluated preoperatively using 3 radiological projections (anteroposterior, lateral and axial). After carrying out a study using computerized tomography with axial, coronal and sagittal reconstructions they were classified using the Sanders classification system from coronal slices.6 In all cases, in both groups the intervention was programmed after obtaining a positive wrinkle test.

Surgical techniqueThe procedure was performed under spinal anaesthesia. The patient was placed in a lateral supine position on the contralateral side to the fractured limb. Underneath and behind the fractured limb sheets or pillows were placed so that the affected leg was parallel to the floor. The imaging amplifier was positioned at the feet of the patient, on the opposite side to the fracture and with a angulation of 45°. This meant that lateral, axial and Broden images were satisfactorily available during the intervention.

A lateral “L” approach was used; once the flap is designed it is necessary for a Steinmann or transfixing pin to be placed in the posterior tuberosity of the calcaneus so that during traction, the posterior facet may be reduced. For reduction of the posterior facet our reference was the medial fragment of the articular facet, which is usually a continuation of the sustentaculum tali. We performed a provisional reduction of the joint fracture with Kirschner pins. Fluoroscopy was used to check for possible step-offs or malrotation defects of the fragments. Once the correct reduction was confirmed, plate osteosynthesis was performed. After this the skin flap was sutured with single filament, with or without drainage, and a compression dressing was applied.

Postoperative protocolThe immediate postoperative protocol consisted in keeping the ankle and leg elevated. In cases of moderate to severe inflammation, an initial dose of corticosteroid was administered (80mg of methylprednisolone) after surgery and a dose after 24h (40–60mg of methylprednisolone). A compression bandage was applied. If drainage was used, it was withdrawn during the first 24h. Twenty four hours after surgery early treatment was initiated with isometric exercises of the quadriceps and hamstrings and active mobilisation of the ankle. Walking aids were prescribed for the operated limb for 12 weeks, with partial load-bearing starting after 12 weeks and total load-bearing at 16 weeks. Check-ups in the outpatient department of our hospital took place after 3 weeks, then 3 and 6 months after surgery, with X-ray controls.

Means of evaluationAge, sex, comorbidities (smoker or diabetic), type of fracture according to Sanders classification system, days of delay to surgery, presurgical complications and length of hospital stay were recorded. To evaluate the radiological results measurements were taken at 3 times: prior to surgery, immediately after surgery and at the end of follow-up. The following were recorded: in axial view, the varus angulation of the calcaneus and in lateral view the Böhler's angle and the Gissane's angle.

To assess loss of reduction the values were compared with regards to angulation in immediate postsurgical control and at the end of follow-up, with subtraction, where the minuend is the value of the immediate postsurgical angle and the subtrahend the value of the angle in the latest review ([immediate postsurgical angle]−[angle in the latest review]=loss of reduction in grades).Finally, complications and reinterventions in both groups were recorded.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the collected variables, the qualitative variables through percentages and the quantitative variables through central tendency measurements (mean and median) and dispersion (standard deviation) was made.

The analysis was carried out using the SPSS version 20.0. programme.

Qualitative variables, including sex, comorbidities (smoker and/or diabetic), type of fracture according to Sanders classification system and presurgical, postsurgical complications and reinterventions were analysed using the Chi squared test with Yates corrections or the exact Fisher test when necessary. Quantitative variables—age, presurgical delay in days, length of hospital stay, values of X-ray measurements (presurgical, immediate postsurgical, end of follow-up and losses of reduction) were performed using a comparison of means for Independent samples through the Mann–Whitney U test. A significant p value was either equal to or below 0.05.

ResultsCharacteristics of both groupsMean presurgical delay was 7.96 days in Group A and 16.47 in B (p=.0001). Mean postsurgical stay was 4.57 days in Group A and 3.4 in B (p=.004).

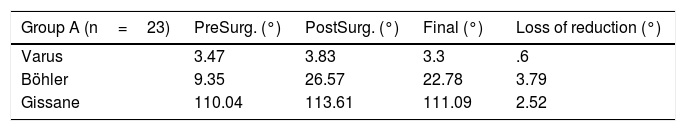

Mean age was 43.35 years in group A and 46.6 years in group B. Most patients were men in both groups, 91.3% en el Group A and 80% in Group B. regarding comorbidities, 2 patients were diabetic in Group B and there were 10 smokers in Group A. in Group A 2 type II fractures were recorded, 17 type III and 4 type IV, and in Group B, 5 type II fractures were recorded, 8 type iii and 2 type iv, in accordance with the Sanders classification system. In Group A a total of 8.7% presurgical complications were recorded compared with 13.3% in Group B, all of them being complications associated with skin problems which were resolved without sequelae (Table 1). They found no statistically significant differences, except that there were more smokers in Group A.

Characteristics of both groups, complications and reinterventions.

| Group A (n=23) | % | Group B (n=15) | % | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 43.35 | 46.6 | .359 | ||

| Men | 21 | 91.3 | 12 | 80 | .365 |

| Diabetes | 0 | 2 | 5.3 | .149 | |

| Tobacco habit | 10 | 4.35 | 1 | 6.7 | 1 |

| Sanders type | |||||

| II | 2 | 8.7 | 5 | 33.3 | .16 |

| III | 17 | 73.9 | 8 | 53.3 | |

| IV | 4 | 17.4 | 2 | 13.3 | |

| Pre-surgical complications | 2 | 8.7 | 2 | 13.3 | .52 |

| Post-surgical complications | 4 | 17.4 | 4 | 26.7 | .385 |

| Reinterventionsa | 5 | 21.7 | 3 | 20 | .615 |

After a mean follow-up of 10 months in Group A and 15 months in Group B, we compared:

- -

Mean presurgical radiological reference values of both groups, with observation of a higher varus angulation in axial x-ray in group B, 5.8°, compared with Group A, 3.47° (p=.003). A lower Böhler’s angle was recorded in Group A, 9.35°, compared with Group B, 15.67° (p=.004). Finally, the Gissane's angle was lower in Group B, 94.27°, compared with Group A, 110.04° (p=.03).

- -

Mean postsurgical radiological reference values of both groups, there were no statistically significant differences between them, with a varus angulation of 3.83° in group A and of 3.21° in B (p=.836), the Böhler’s angle values being 26.57° in Group A and 31.87° in B (p=.114), and the Gissane’s angles values being 113.61° in Group A and 115° in B (p=.535).

- -

Final radiological reference values of both groups. There were no statistically significant differences here either, with a varus angulation of 3.3° in Group A and of 2.8° in B (p=.701), with Böhler’s angle values being 22.78° in Group A and 29.27° in B (p=.059),and Gissane’s angle values being 111.09° in Group A and 110.87° in B (p=.976).

- -

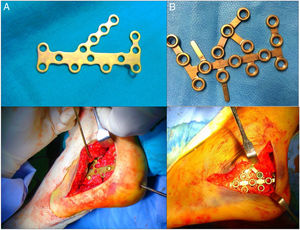

The loss of reduction observed in both groups, where there were no statistically significant differences. This was .6° in Group A and 0.41° in B, with regards to the mean varus angulation (p=1). The Böhler’s angle dropped 3.79° in Group A, compared with 2.6° in Group B (p=.616). Finally, in the Gissane’s angle a loss of reduction was observed, of 2.52°in Group A and 4.13 in B (p=.93) (Table 2).

Table 2.Radiological measurements and loss of reduction.

Group A (n=23) PreSurg. (°) PostSurg. (°) Final (°) Loss of reduction (°) Varus 3.47 3.83 3.3 .6 Böhler 9.35 26.57 22.78 3.79 Gissane 110.04 113.61 111.09 2.52 Group B (n=15) PreSurg. (°) PostSurg (°) Final (°) Loss of reduction (°) Varus 5.80 3.21 2.8 .41 Böhler 15.67 31.87 29.27 2.6 Gissane 94.27 115.0 110.87 4.13 PostSurg.: postsurgical; PreSurg.: presurgical.

Eight complications were recorded, 4 in Group A and 4 in B, all of them linked to the surgical wound (p=.385). Five reinterventions were carried out in Group A and 3 in B (p=.615). In Group A, 3 of them were carried out for the extraction of osteosynthesis material and the remaining 2 consisted in lavages and surgical debridements due to infection of the surgical wound. In Group B 3 interventions were performed, all of which were for extraction of osteosynthesis material (Table 1).

DiscussionCurrent evidence in treatment of calcaneal joint fractures endorsed surgical treatment.7 Among the objectives of surgical treatment is the restoration of Böhler’s8 angle, regardless of the presentation angle because this is the best predictor of long-term favourable outcome.9,10 The development of locking plates could lead to an improvement in fatigue failure or loss of reduction over time.4,11–13

Hyer et al.14 in their study analysed the radiological outcome of locking plates in calcaneal fractures and did not observe losses of: height, joint reduction or fixation, suggesting that the results were probably due to the inherent stability of the construction of the locking plate. Santosha et al.15, in a study where the objective was to assess the functional result in intraarticular calcaneal fractures operated using an “L” approach and osteosynthesis with calcaneal locking plates, obtained good functional and radiological results after 2 years of follow-up. They reported that this osteosynthesis maintains the Böhler’s angle. However, none of the previous studies used a control group with conventional plates.

In the only comparative study we found in the literature with similar characteristics to ours—intraarticular calcaneal fractures, “L” approach and osteosynthesis with locking plates versus non locking plates—published by Chen et al.16, after a follow-up of between 2 and 3 months, they observed a reduction in the Böhler’s angle of 3° in the group with locking plates compared with 7° in the group without locking plates. In our series, after a 10 and 15 month follow-up, we observed similar results, with a higher loss of reduction in the Böhler’s angle in the group with patients with non locking plates (3.79°) compared with the group of patients with locking plates (2.6°). In our series we also found a greater loss of varus angulation in the patient group with non locking plates, .6 versus 0.41°, and, paradoxically, a greater loss in the Gissane’s angulation in the group of patients with locking plates, 4.13 versus 2.52°. Thus, although these differences were not statistically significant, we refer to the loss of reduction in the Böhler’s angles in patients operated on with conventional plates, since this is the best predictor of a good long-term outcome for patients.9

Among the limitations of our study we observed that this was a short series, with a medium-term follow-up. It was homogeneous in approach and type of plate and also in pre and postoperative protocol. In both groups, the “L” approach was used and the plate was similar in pin shape, size and location. From the viewpoint of patient characteristics there was uniformity in everything except for smoking habits which were far more frequent in the decade between 1997 and 2007, where the historical cohort was selected from. However, this difference did not appear to impact the comparison outcome. The differences found between the groups were not statistically significant, and studies are needed with a larger sample size to provide evidence in this area.

ConclusionIn our study we did not observe any significant differences between the two groups with regard to the loss of radiological reduction, complications and reinterventions. However, we did observe a high loss of reduction in the Böhler’s’s angle in patients who were operated on using conventional plates.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence ii.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Correoso Castellanos S, García Galvez A, Lajara Marco F, Blay Dominguez E. Fracturas intraarticulares de calcáneo. ¿Las placas bloqueadas mantienen la reducción mejor que las convencionales? Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;63:383–388.