To follow up pain in the immediate postoperative period, using an elastomeric pump in anterior cruciate ligament surgery.

Material and methods309 patients who had undergone anterior cruciate ligament repair with bone-tendon-bone allograft. Pain control was assessed with a visual analogue scale (VAS) during the immediate postoperative period, in the postoperative care unit, in the recovery room, and after the first 24–48–72h following home discharge. The need for rescue medication, adverse effects observed and emergency visits were also registered.

Results309 patients were assessed (264 males, 45 females), mean age 33 (range: 18–55). Postoperative pain was mild in 44.7% of patients, and 38.5% were pain-free. At discharge, 41.1% of patients reported mild pain and 57% were pain-free. At home, mild to moderate levels of pain were maintained and over 97% of patients presented VAS values ≤3. Fewer than 3% had adverse effects, 8.7% had to use analgesic medication at some point. Pruritus occurred in less than 1% of patients receiving intravenous analgesia at home, and fewer than 2% had device-related complications.

DiscussionThere is no consensus regarding the postoperative management of anterior cruciate ligament lesions, although most surgeons use multimode anaesthesia and different combinations of analgesics to reduce postoperative pain.

ConclusionsThe use of an intravenous elastomeric pump as postoperative analgesia for anterior cruciate ligamentoplasty has yielded good results.

Hacer un seguimiento del dolor en el posoperatorio inmediato, mediante el uso de bomba elastomérica en la cirugía del ligamento cruzado anterior (LCA).

Material y métodosTrescientos nueve pacientes intervenidos de ligamentoplastia del LCA mediante plastia autóloga de hueso-tendón-hueso. Durante el posoperatorio inmediato se realizó un seguimiento del dolor mediante escala visual analógica (EVA); tanto en la unidad de reanimación posoperatoria, como en la sala de adaptación al medio, y durante las primeras 24–48–72h en el domicilio. Registramos también la necesidad de medicación de rescate, efectos adversos observados y visitas al servicio de urgencias.

ResultadosSe estudió a 309 pacientes (264 varones, 45 mujeres) con una edad media de 33 años (rango: 18–55). El 44,7% de los pacientes reportaron dolor posoperatorio inmediato leve y el 38,5% no tenía dolor. Al alta, el 41,1% de los pacientes reportaron dolor leve y el 57% no tenía dolor. En domicilio, se mantuvieron los valores de dolor leve/moderado, con más del 97% de los pacientes con valores EVA ≤3. Se registraron efectos adversos en menos del 3% de los casos. El 8,7% de los casos tuvo que hacer uso en algún momento de medicación analgésica. Menos del 1% presentó prurito mientras llevaban la analgesia intravenosa en el domicilio y menos del 2% presentó problemas relacionados con el dispositivo.

DiscusiónActualmente, no hay consenso en cuanto al manejo posoperatorio de las lesiones del LCA, aunque la tendencia es el uso de anestesia multimodal y de sistemas para reducir el dolor posoperatorio.

ConclusionesEl uso de bomba elastomérica como procedimiento ambulatorio de control del dolor en la reparación del ligamiento cruzado anterior ha reportado buenos resultados.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) surgery is a common procedure, particularly in arthroscopic treatment. Good postoperative pain control is very important for good rehabilitation and satisfactory final functional outcomes. Even so, more than 60% of patients who undergo this surgery experience moderate to severe pain with conventional oral analgesic regimens,1 such as alternating paracetamol with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, plus a rescue drug like tramadol.2,3

This operation is currently increasingly being undertaken in the form of day-case surgery.2,4 There are many studies that have demonstrated that outpatient ACL surgery is safe and effective, and with good pain control there is no increase in the need for rehospitalisation and/or complications.2,5

Most of the published articles present the circuits that these patients undergo when they receive nerve block analgesia by infusion on discharge.6,7

The Spanish Association of Major Ambulatory Surgery (Asociación Española de Cirugía Mayor Ambulatoria) (ASECMA) underwrite a decologue, which is the first consensus document endorsed by other medical and surgical societies, and indicate that a multidisciplinary, multimodal and individualised approach should be taken to pain.4 The advent of elastomeric infusers, and drug infusion pumps have proved a major advance in the administration of all sorts of drugs for the treatment of postoperative pain. Maintenance of stable plasma levels have resulted in better pain control, improved efficacy and reduced side effects compared with the administration of bolus medication.2

The objective of this study was to present the results of the pain control and complications protocol that we use in our centre, for patients who undergo arthroscopic ACL reconstruction as day cases in our department and receive postoperative pain control through a continuous intravenous infusion pump (elastomeric pumps).

Material and methodsA retrospective study was undertaken of a consecutive series from 2009 to 2015, which included 309 patients who had undergone ACL ligamentoplasty with bone-tendon-bone (BTB) autologous plasty. The BTB allograft technique was employed for reconstruction of the ACL. The anaesthetic technique was chiefly by laryngeal mask (in 243 patients), only the initial 66 patients received spinal anaesthesia, and no locoregional block was used in any of the cases. All the patients received preoperative prophylaxis of 2g cefazolin perfused 20min before performing the tourniquet, which was routinely used. The femoral tunnel was prepared through the transtibial portal and the plasty was fixed to the tunnels by metal interference screws. Before closing the wound, haemostasis was performed plus infiltration of 20cc of 0.25% levobupivacaine through the wound and the portals. Staples were used for wound closure and no drains were placed in any case. A splinted pressure bandage was placed, which was removed after one week. Partial weight bearing with crutches was allowed on discharge.

Since 2009, the great majority of arthroscopic ACL reconstructions have been performed as day cases.

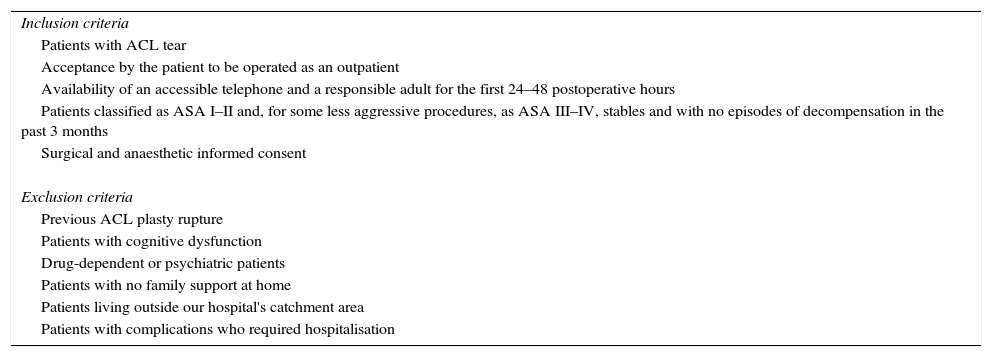

Table 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria for major ambulatory surgery (MAS) for ACL repair in our centre.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for ACL repair as MAS.

| Inclusion criteria |

| Patients with ACL tear |

| Acceptance by the patient to be operated as an outpatient |

| Availability of an accessible telephone and a responsible adult for the first 24–48 postoperative hours |

| Patients classified as ASA I–II and, for some less aggressive procedures, as ASA III–IV, stables and with no episodes of decompensation in the past 3 months |

| Surgical and anaesthetic informed consent |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Previous ACL plasty rupture |

| Patients with cognitive dysfunction |

| Drug-dependent or psychiatric patients |

| Patients with no family support at home |

| Patients living outside our hospital's catchment area |

| Patients with complications who required hospitalisation |

On arrival at the surgical outpatients department, an intravenous line was placed in the patient's non-dominant forearm, where the elastomeric pump was later attached. Approximately 20min before surgery, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (dexketoprofen 50mg) and a corticosteroid (dexamethasone 4/8mg according to body weight) were administered intravenously, as preventive analgesia and as prophylaxis for nausea and vomiting, either induced by subsequent tramadol administration or the general anaesthetic itself.3,8

In all cases, the elastomeric pump was started in the postoperative care unit (POCU). After immediate anaesthetic recovery, the patients were transferred to the recovery room (RR), until they were in a condition to leave the hospital. The visual analogue scale (VAS) was used to assess pain levels, in the hospital (POCU and RR), and after the first 24–48–72h at home. The need for rescue medication, adverse effects and visits to the emergency department were also monitored.

Elastomeric regimen 1 was used in 229 patients (74.1%) (400mg tramadol+250mg dexketoprofen+2.5mg haloperidol in 100cc physiological saline, for 48h) and elastomeric regimen 2 was used in 74 patients (23.9%) (400mg tramadol+12g metamizole+2.5mg haloperidol in 100cc physiological saline, for 48h. Short regimens of 24h were only used in 6 patients (1.9%), and at the beginning of the study. These were replaced by the current 48h regimens.

Currently regimen 1 is routinely used, unless the patient suffers from an ulcerative condition, high blood pressure with 2 or more drugs, or an allergy to dexketoprofen, when regimen 2 is used, which contains metamizole. In addition to the pump, patients were advised, when they left the surgical outpatients department, to take paracetamol 1g every 6h orally, a gastric protector such as 20mg omeprazole every 24h orally and 10mg metoclopramide every 12h orally if they were to experience nausea and/or vomiting. Twenty-four hours following the procedure, the home care unit contacted the patient by telephone to enquire about their general condition and pain using the VAS, onset of side effects, need for rescue analgesia or possible visit to the emergency department. If the patient presented no associated problems, the unit visited the patient at home, where they were reassessed, and the elastomeric pump was removed. At that time, the patient followed an oral regimen of 1g paracetamol alternated with 600mg ibuprofen orally every 4h, plus 20mg omeprazole every 24h and 50mg tramadol, if required for pain. After 72h the patients were again contacted by telephone to assess their pain.

A week after the operation, the patients were seen by their surgeon in the outpatient clinic, immobilisation was discontinued and rehabilitation started. During this first postoperative week, the patients were allowed to fully weight bear with the help of 2 crutches.

ResultsOf the 309 patients operated, 264 were male and 45 female, with a mean age of 33 years (range from 18 to 55 years).

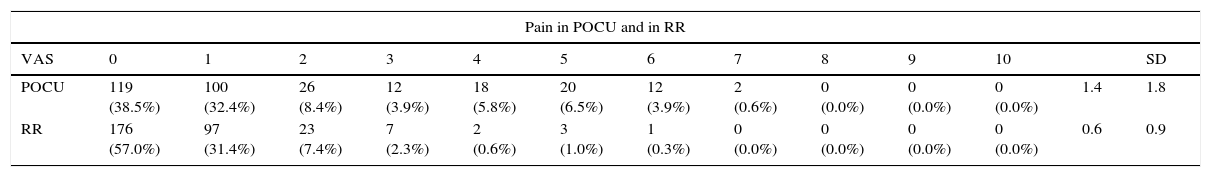

Table 2 shows the progression of the operated patients’ pain. In general, it can be observed that the majority of the patients had no, or mild pain during their hospital stay or at their home follow-up visits at 24, 48 and 72h after surgery. A reduction of the mean pain scores from 1.4 (SD=1.8) POCU, to 0.6 (SD=0.9) RR. At home, the levels dropped to 0.6 (SD=0.9) after 24h to 0.4 (SD=0.9) after 72h.

Postoperative pain.

| Pain in POCU and in RR | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | SD | |

| POCU | 119 (38.5%) | 100 (32.4%) | 26 (8.4%) | 12 (3.9%) | 18 (5.8%) | 20 (6.5%) | 12 (3.9%) | 2 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1.4 | 1.8 |

| RR | 176 (57.0%) | 97 (31.4%) | 23 (7.4%) | 7 (2.3%) | 2 (0.6%) | 3 (1.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Pain at home | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | SD | |

| 24h | 156 (50.5%) | 138 (44.7%) | 4 (1.3%) | 4 (1.3%) | 2 (0.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | 3 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| 48h | 162 (52.4%) | 135 (43.7%) | 2 (0.6%) | 1 (0.3%) | 5 (1.6%) | 4 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| 72h | 210 (68.0%) | 87 (28.2%) | 2 (0.6%) | 1 (0.3%) | 4 (1.3%) | 5 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.4 | 0.9 |

Of the 309 operated patients, 27 (8.7%) had to use analgesic medication at some point, with 50mg tramadol every 8h.

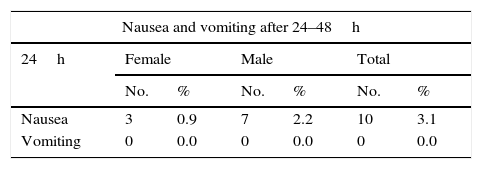

The adverse effects recorded were the onset of postoperative nausea and vomiting, often intravenous analgesia-related, and drowsiness. Table 3 shows the frequency of adverse effect per sex. Few side effects were observed, with no differences between the sexes. Only 10 patients (3.2%) presented nausea after 24h and 2 (0.6%) after 48h. Four patients (1.3%) presented vomiting after 48h and none of the patients reported vomiting after 24h. Four patients (1.3%) reported drowsiness after 24h, which disappeared entirely after 48h.

Adverse effects.

| Nausea and vomiting after 24–48h | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24h | Female | Male | Total | |||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Nausea | 3 | 0.9 | 7 | 2.2 | 10 | 3.1 |

| Vomiting | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 48h | Female | Male | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Nausea | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.6 |

| Vomiting | 2 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.6 | 4 | 1.3 |

| Drowsiness 24–48h | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24h | Female | Male | Total | |||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Drowsiness | 4 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 1.3 |

| 48h | Female | Male | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Drowsiness | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

In addition, 3 patients (1.0%) presented pruritis during the administration of intravenous analgesia at home.

In terms of issues with the elastomeric device, it is worth highlighting that there was extravasation of the peripheral line in 4 (1.3%) patients, which was resolved by the home care unit. Finally, one patient burned the extension lead of their elastomeric pump with a cigarette, which had to be removed.

The visits that the patients made to our hospital's emergency department during the first week were recorded, just before the visit to their surgeon in the outpatient clinic. Of the 309 patients, 22 had to attend the emergency departments with problems associated with the bandage. Of these patients, 12 had joint effusion, and of these 8 had effusion under tension. All the cases improved when the bandage was checked and the symptoms of all the cases of effusion under tension improved after evacuation by arthrocentesis. Only one case attended the emergency department with acute surgical wound infection, which was resolved with debridement and oral antibiotic therapy.

DiscussionGood postoperative pain control is one of the keys to the success of MAS, as well as the patient's level of satisfaction. In MAS, postoperative pain, nausea and vomiting are still causes for delayed hospital discharge and readmission.9

Therefore, in order to introduce more complex procedures into ambulatory surgery, it is essential to improve these factors, since oral analgesia has sometimes proved insufficient.

Arthroscopic reconstructive ACL surgery is an optimal procedure to be undertaken in MAS programmes, if we can ensure good postoperative analgesia. The practice of multimodal analgesia is currently very widespread, using different analgesic techniques and thus minimising side effects.6,10–12

In our hospital, the ambulatory surgery department is an easily accessed separate building, for low- and medium-complexity procedures. We opted for continuous intravenous analgesia at home because we believe that it is better suited to our social environment and health structure.2 There is currently a great tendency to place perineural and peri-incisional catheters. Reviewing the literature, we found that the rate of complications, especially nerve complications, is very low, but when they do occur there is no rapid resolution.7,13 Nerve blocks can also be helpful in managing postoperative pain in cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery,14 although a motor block can be uncomfortable in terms of the patient's autonomy.

This analgesic procedure enabled us to provide our patients good analgesia and wellbeing. Moreover, the patients felt safe with home visits from nursing staff to support them.1,2,4,5

There are studies that compare the results between surgery with admission and ambulatory surgery in surgical cruciate ligament repair, and note that there are no differences in terms of safety between the 2 techniques.14,15 These studies, however, are smaller series than ours and used multimodal anaesthesia systems with blocks and oral medication.16,17

Krywulak et al.18 performed a randomised study on the degree of satisfaction among patients who were treated as outpatients and as inpatients, and noted that the patients who were not admitted to hospital had a higher degree of satisfaction. Although this was a study with very few cases, this also indicates that treatment without hospital admission is more satisfactory for patients. We confirm this in our study with far more case studies.

Other studies describe good results with elastomeric pumps. Hoenecke et al.19 reported less pain and less need for narcotics in patients operated for ACL who followed an ambulatory continuous infusion regimen of bupivacaine through the surgical wound via an elastomeric pump for the first 48h. López Alvarez et al.20 performed continuous femoral nerve blocks using bupivacaine via an elastomeric pump for the first 24h, with good pain control. However, they described the incidence of surgical infection and motor block as complications.

ConclusionsWe consider that the use of ambulatory elastomeric pumps after ACL reconstruction achieved good results on discharge, with few complications, compared to other procedures that use elastomeric pumps for direct infusion of the wound or for locoregional block. This procedure, however, requires the support of a home care unit, which some hospitals lack.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the research was carried out according to the ethical standards set by the responsible human experimentation committee, the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their centre of work regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Villalba J, Peñalver J, Torner P, Serra M, Planell J. Analgesia intravenosa domiciliaria mediante bomba elastomérica como procedimiento ambulatorio de control del dolor en la reparación del ligamento cruzado anterior. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2018;62:65–70.