To evaluate the short term and 1-year follow-up functional effects of a physiotherapy programme in patients over 60 years of age with massive and irreparable Rotator Cuff (RC) tear.

MethodsA total of 96 patients with massive and irreparable RC tear were prospectively recruited. All patients were treated with a 12-week physiotherapy programme. Three evaluations were performed, at the beginning, at the end of the treatment and at one year of follow-up. The Constant–Murley questionnaire was used to assess shoulder function, the DASH questionnaire for upper limb function, and the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain intensity.

ResultsAt the end of the treatment, all the variables showed a clinically and statistically significant difference (p<.05). At one year of follow-up, the Constant–Murley showed an increase of 26.5 points (Cohen's d=1.7; 95% CI: 23.5–29.5; p<.001), DASH showed a decrease of 31.4 points (Cohen's d=2.2; 95% CI: 28.5–34.3; p<.001), and the VAS showed a decrease of 3.9cm (Cohen's d=3.6; 95% CI: 3.6–4.1; p<.001).

ConclusionIn the short term and 1-year follow-up, a physiotherapy programme showed clinically and statistically significant results in all functional variables in patients older than 60 years with massive and irreparable RC tear.

Evaluar los efectos funcionales a corto plazo y al año de seguimiento de un programa de fisioterapia en pacientes mayores de 60 años con rotura masiva e irreparable del manguito rotador (MR).

MétodoSe reclutaron de forma prospectiva 96 pacientes con rotura masiva e irreparable del MR. Todos los pacientes fueron tratados con un programa de fisioterapia de 12 semanas de duración. Se realizaron tres evaluaciones, al inicio, al finalizar el tratamiento y al año de seguimiento. Se utilizó el cuestionario de Constant-Murley para evaluar la función del hombro, el cuestionario DASH para la función del miembro superior y la escala visual analógica (EVA) para la intensidad del dolor.

ResultadosAl finalizar el tratamiento, hubo mejoría clínicamente relevante y estadísticamente significativa (p < 0,05) en todas las variables. Al año de seguimiento, el Constant-Murley mostró un incremento de 26,5 puntos (d de Cohen = 1,7; intervalo de confianza (IC) 95% 23,5 a 29,5; p < 0,001), el DASH mostró una disminución de 31,4 puntos (d de Cohen = 2,2; IC 95% 28,5 a 34,3; p < 0,001), y la EVA mostró una disminución de 3,9 cm (d de Cohen = 3,6; IC 95% 3,6 a 4,1; p < 0,001).

ConclusiónA corto plazo y al año de seguimiento, un programa de fisioterapia consiguió mejoría clínica y estadísticamente significativa en todas las variables funcionales en pacientes mayores de 60 años con rotura masiva e irreparable del MR.

Massive rotator cuff (RC) tears are a major clinical problem, and currently there are several criteria for diagnosing them. For Cofield and DeOrio1,2 this corresponds to a diameter higher or equal to 5cm, and for Gerber3 it is a compete tear of two or more. Davidson and Burkhart4 incorporate the tear pattern into their system of classification. For them, massive tear should have a coronal and sagittal length higher or equal to 2cm. Recently, Collin et al.5 divided the RC tear topographically into five components and they directly related it with the shoulder function. Despite this, there was no consensus about which of these criteria was better for defining and classifying massive RC tear.6–8

Studies have reported several rates of prevalence, although it was estimated that the massive tears represented between 10% and 40% of the total RC tears.9 Massive tears are rarely due to an acute lesions, they are generally chronic in development and are associated with a series of degenerative changes such as myotendinous retraction, loss of musculotendinous elasticity, fatty infiltration of the muscles and static superior subluxation of the humerus head.10 When superior migration of the humeral head produces an acromiohumeral interval under 7mm and this is also combined with a grade 3 or 5 fatty infiltration, according to Goutallier's classification, the probability of surgical repair success is very low, and this is therefore called massive and irreparable RC tear.8,10

RC tears increase with age, and it has been estimated that at 66 years of age the prevalence of having this clinical condition increases by 50%.9,11 In the older adult, the most clinically common symptoms are pain and partial or total loss of the upper limb function.12 Despite the high prevalence of this age group, therapeutic management is still under controversy.5,7–10,13 For Tashjian,14 all adult patients with massive and/or irreparable RC tears should begin with a conservative treatment. However, the systematic review of Ainsworth et al.15 concluded that the effectiveness of physiotherapy and therapeutic exercise in this clinical condition has not been well established, despite the review by Edwards et al.16 showing that conservative treatment is effective in between 73% and 80% of patients with RC tear. The systematic review of Downie et al.17 showed that evidence is insufficient for guaranteeing the efficacy of conservative management in older adult patients with RC tears.

In addition to this, few prospective studies reported long-term functional effects in patients with massive, irreparable RC tears.18–20 Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the short-term functional effects and after one year of follow-up of a physiotherapy programme in patients over 60 years of age with massive and irreparable RC tears

Material and methodsThis prospective, observational study was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Central Metropolitan Health Service of Chile (reference number 048975). Between February 2017 and February 2019, 96 patients over 60 years of age with massive and irreparable RC tears were recruited prospectively. Diagnosis was made by two orthopaedic surgeons, and the evaluation of images was based on radiological studies, scans and magnetic nuclear resonance. Patients with massive tears were included, i.e. a complete tear of two or more tendons,3 and irreparable with a grade 3 or 4 fatty infiltration, according to Goutallier's classification, or grade 3 according to Fuchs’classification.21,22 Patients with acute traumatic lesions of the RC were excluded, or with other pathologies of the shoulder joint complex (proximal humerus fracture, adhesive capsulitis, glenohumeral instability, etc.) and with previous surgery of the affected shoulder

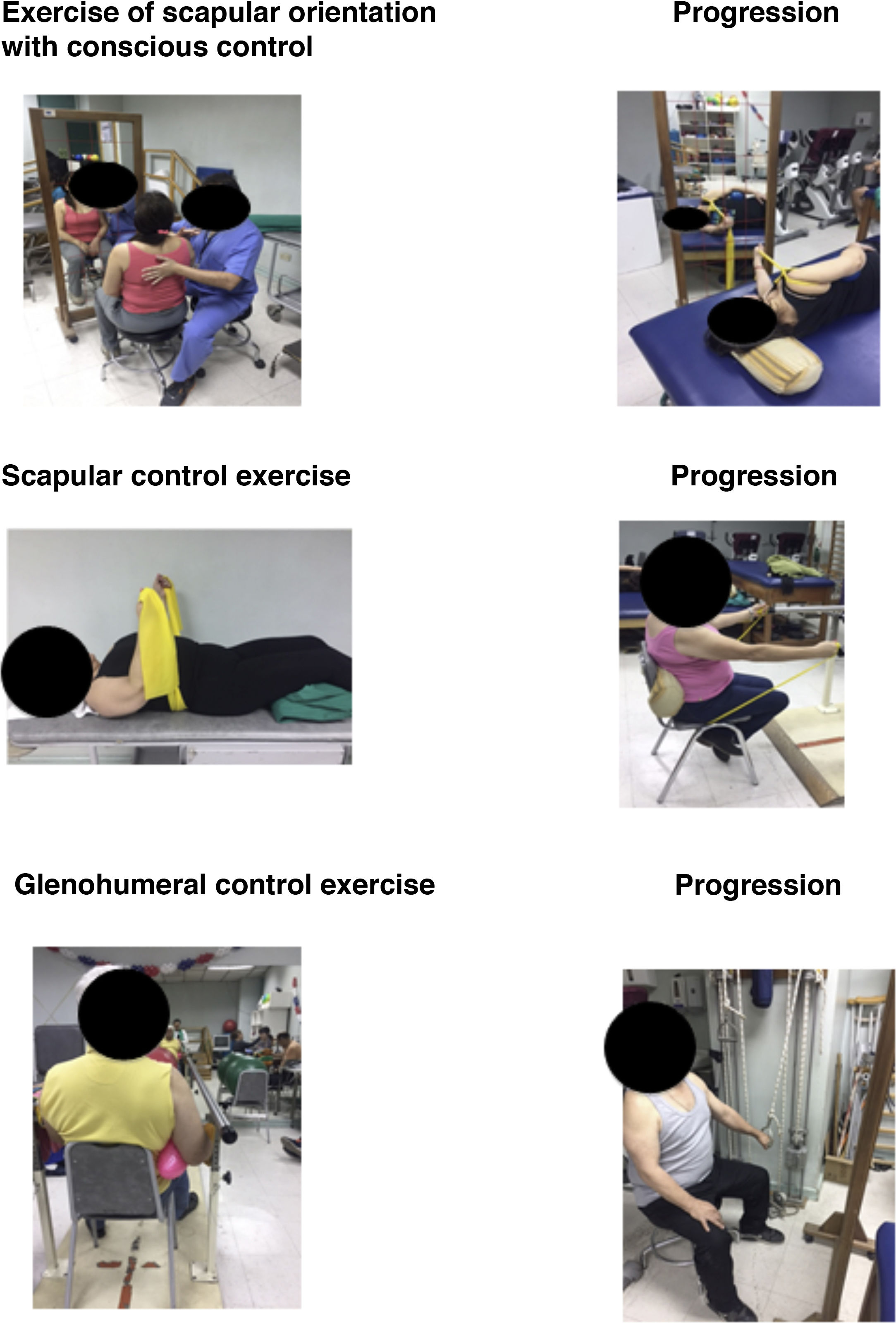

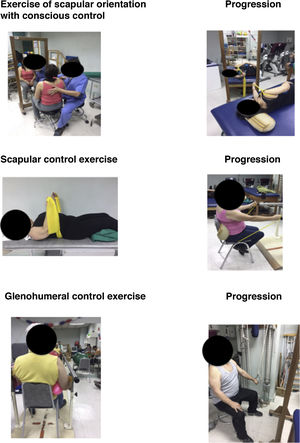

InterventionsAll patients received a physiotherapy programme, taking as reference an algorithm which was agreed upon by expert clinicians.23 The programme began with muscle awareness control exercises to improve proprioception ands normalise the scapular and glenohumeral rest position and were then prescribed selective activation exercises for the upper rotation and posterior scapular inclination, finally ending with glenohumeral exercises to restore the centralisation and prevent upper translation of the humeral head (Fig. 1). The general principles of the programme were: (i) the exercises should not lead to pain, only to levels of light or moderate pain after the session, which would last for a maximum of 12h; (ii) a maximum of four types of exercises per session; (iii) the programme started with low load exercises, emphasising the quality of the motor task performance, with exercises performed slowly, mindfully and progressively, slowly reducing feed-back, until the exercises were performed subconsciously and automatically.23

In addition to this, three manual orthopaedic therapy techniques were performed to restore the range of joint movement. The posterior glenohumeral mobilisation technique was applied,24 along with scapular mobilisation25 and sternoclavicular mobilisation.26 Ten repetitions of each technique were performed with a minute rest between each one. The physiotherapy programme had a periodicity of two weekly sessions and a duration of 12 weeks.

Outcome measurementsAll patients were assessed on three occasions, at the start of the physiotherapy programme, on the twelfth week after treatment termination and after one year of follow-up. Assessment consisted of a physical examination and the completion of functional questionnaires. Two physiotherapists outside the research team performed all assessments.

The measurement of the main outcome was the assessment of the shoulder function with the a Constant-Murley27 questionnaire, which is one of the specific most frequently used tools and recommended for shoulder functionality.28 A cross-cultural adaptation into Spanish was used, the version of which showed good validity and reliability.29 One study showed that an increase of 10 points was considered a minimal clinically important difference.30

Secondary outcome measurements were the assessment of upper limb function with a questionnaire on shoulder, forearm and hand disability (DASH).31 A cross-cultural adaptation into Spanish was used, the version of which showed excellent results with regard to validity, reliability and sensitivity to change.32 One study showed that there was a reduction of 15 points that was considered a minimal clinically important difference.33 Finally, to assess pain intensity the visual analogous scale or VAS was used, which is a one-dimensional, simple and reproducible assessment method. 34 One study showed that a reduction of 1.4cm was considered to be a minimal clinically important difference.35

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. The continuous variables were presented as a mean and standard deviation (SD) and the categorical variables in number and percentage. Data distribution was analysed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and with the probability graphics to determine the contrast of hypotheses to be used.

Factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the differences between the baseline data, on termination of treatment at 12 weeks and at one year of follow-up. After this, a homoscedasticity analysis was used with the Levene test to assess the homogeneity of variances and to identify the differences between the three measurements the post hoc correction of Bonferroni was used. Finally, to determine the magnitude of the changes, the size effect with Cohen's d was estimated, with the following effects: small d=.2, medium d=.5 and large d=.8.36 Statistical significance was established as p<.05 with their respective confidence intervals (CI) of 95%. Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS IBM version 24 software (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY).

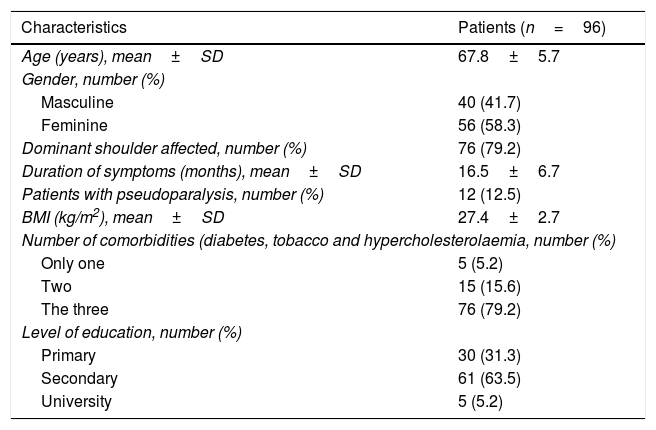

ResultsBaseline characteristics of the group studied are presented in Table 1. During the study there were no losses or withdrawals and when the physiotherapy programme was finalised no patient reported associated complications with the treatment received. Out of the total patients, only 15 (15.6%) had to begin to take analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs after termination of physiotherapeutic treatment. Within this group there were 12 patients (12.5%) with pseudo paralysis.

Baseline characteristics of patients over 60 years of age with massive and irreparable RC tears.

| Characteristics | Patients (n=96) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 67.8±5.7 |

| Gender, number (%) | |

| Masculine | 40 (41.7) |

| Feminine | 56 (58.3) |

| Dominant shoulder affected, number (%) | 76 (79.2) |

| Duration of symptoms (months), mean±SD | 16.5±6.7 |

| Patients with pseudoparalysis, number (%) | 12 (12.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD | 27.4±2.7 |

| Number of comorbidities (diabetes, tobacco and hypercholesterolaemia, number (%) | |

| Only one | 5 (5.2) |

| Two | 15 (15.6) |

| The three | 76 (79.2) |

| Level of education, number (%) | |

| Primary | 30 (31.3) |

| Secondary | 61 (63.5) |

| University | 5 (5.2) |

BMI: body mass index; RC: rotator cuff; SD: standard deviation.

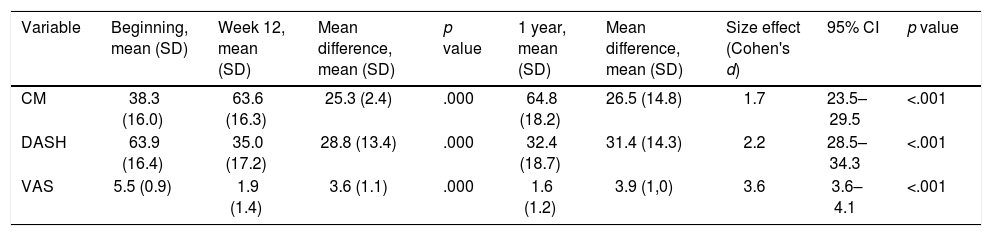

On finalising the physiotherapy programme, all the variables assessed presented with a clinical and statistically significant difference (p<.05). Table 2 showed the values of the results assessed at the beginning, after the end of week 12 and after one year of follow-up and also the effect of the treatment. When comparing the Constant-Murley questionnaire between the beginning of the programme and one year after follow-up there was an increase of 26.5 points (Cohen's d=1.7; 95% CI: 23.5–29.5; p<.001), the DASH questionnaire showed a reduction of 31.4 points (Cohen's d=2.2; 95% CI: 28.5–34.3; p<.001), and VAS showed a reduction of 3.9cm (Cohen's d=3.6; 95% CI: 3.6–4.1; p<.001). All the variables assessed showed an improvement higher than the difference considered as clinically important minimal.

Comparison of results between the beginning, when treatment finished at week 12 and after one year of follow-up.

| Variable | Beginning, mean (SD) | Week 12, mean (SD) | Mean difference, mean (SD) | p value | 1 year, mean (SD) | Mean difference, mean (SD) | Size effect (Cohen's d) | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM | 38.3 (16.0) | 63.6 (16.3) | 25.3 (2.4) | .000 | 64.8 (18.2) | 26.5 (14.8) | 1.7 | 23.5–29.5 | <.001 |

| DASH | 63.9 (16.4) | 35.0 (17.2) | 28.8 (13.4) | .000 | 32.4 (18.7) | 31.4 (14.3) | 2.2 | 28.5–34.3 | <.001 |

| VAS | 5.5 (0.9) | 1.9 (1.4) | 3.6 (1.1) | .000 | 1.6 (1.2) | 3.9 (1,0) | 3.6 | 3.6–4.1 | <.001 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; CM: Constant–Murley questionnaire; DASH: disability of shoulder, forearm and hand questionnaire; SD: standard Deviation; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale.

Our results showed a clinical and statistically significance improvement in the short term of all the variables assessed. Also, these functional improvements continued one year after follow-up in patients above 60 years of age with massive and irreparable RC tear.

The therapeutic management of massive RC tears in older adults is controversial, with many proposals for therapeutic options being made but without any consensus being reached.5,7–10 Several factors contributed to this lack of consensus. The definition of “massive” tear is not clearly standardised, there are several classification systems with different criteria for defining it.1–5 In our study we used the criterion proposed by Gerber et al.,3 although the fatty infiltration is an irreversible condition that has a negative impact on the outcomes of surgical RC repair,8,10,37 although a clear relationship has not been established between patient symptoms and the response to physiotherapeutic treatment.5 Although it is true that older adults are a population group of particular interest, due to the fact that RC tears are increasingly prevalent with age and may have a significant effect on the function and quality of life, evidence is insufficient to ensure the efficacy of surgical treatment vs. conservative treatment in this group.17

In our study we used a standardised physiotherapy programme based on a clinical decision algorithm proposed by a consensus of experts. The selection and prescription of exercises in this programme was made based on clinical findings and not on structural deterioration, using the principle of muscle selectivity to correct the muscular deficits associated with RC tear.23 For this reason low load, low activation exercises should be begun with, with no pain, with arms below the shoulders, emphasising the quality of the motor task performance, in a slow, mindful and progressive manner. There is then progression of exercises in prone and side positions, selectively activating low activation muscles such as the anterior serratus and inferior trapezoid, with minimal activation of hyperactive muscles such as the superior trapezoid and deltoids, thus avoiding muscle fatigue and increasing symptoms.23

We also used three manual therapy techniques to restore the range of joint movement. Posterior glenohumeral mobilisation has demonstrated its effectiveness in improving the range of glenohumeral movement, particularly external rotation in patients with adhesive capsulitis.24,38 Scapular mobilisation techniques have also demonstrated how effective they are in patients with adhesive capsulitis,39 and the sternoclaviular mobilisation has shown improvements in function and reduction of pain in patients with massive and irreparable RC tears.26

Several studies have evaluated the effects of a short and/or medium term physiotherapy programme,40–43 but few studies have assessed the effects long term in patients with massive and irreparable RC tears.18–20 With similar results to those obtained in our study, Kijima et al.18 showed that 13 years after having been diagnosed, 90% of patients of advanced age who had been treated conservatively, had no pain and that 75% did not present with any functional limitation in their daily life activities. Collin et al.19 showed that elongation of the minor pectoral muscles, superior trapezium and scapular elevators, in combination with a priopioceptive exercise programme with centralisation of the humeral head, strengthening exercises of the scapular muscles and re-education of the deltoid muscles improved shoulder functions after two years of follow-up and that over 50% of patients recovered up to 160° of shoulder flexion. Agout et al.20 showed that conservative treatment presented with significant functional improvements after six months and that these remained one year after follow-up. In contrast, Yian et al.44 showed that a programme of exercises based on the re-education of the anterior deltoid muscles, after three months of treatment and two years of follow-up did not produce a significant functional improvement in patients with massive and irreparable RC tear.

The presence of pseudo paralysis, defined as a loss of active flexion below 90° with the preservation of passive movement of the shoulder range,5,7 is a factor which negatively impacts functional outcomes. In our study, patients who presented this clinical condition had the worst functional outcomes and they all continued to use analgesic and anti-inflammatory drugs when the physiotherapy treatment terminated. In addition to this, after one year of follow-up five of them were surgically operated on for the implantation of a subacromial ball and two were operated on for arthroplasty of the shoulder with an inverted prosthesis. In keeping with our findings, the Dickerson et al.45 review showed that a rehabilitation programme has a very low possibility of reversing or improving functional outcomes of patients with secondary pseudo paralysis to a massive and irreparable RC tear.

This study had several limitations. As it was an observational study of a case series there was no control group and neither was a random sampling strategy used for patient selection. No image evaluation at the end of follow-up took place. All these limitations suggest our results should be interpreted with caution.

ConclusionIn the short term and one year after follow-up a physiotherapy programme achieved clinical and statistically significant improvement in all functional variables in persons over 60 years of age with massive and irreparable RC tears.

Ethical aspectsThe study was approved on 13 February 2017 by the Ethics Committee of the Central Metropolitan Health Service of Chile.

FinancingThis study did not receive any type of financing.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gutiérrez-Espinoza HJ, Lorenzo-García P, Valenzuela-Fuenzalida J, Araya-Quintanilla F. Resultados funcionales de un programa de fisioterapia en pacientes con rotura masiva e irreparable del manguito rotador. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2021;65:248–254.