To determine the risk factors associated with prosthetic knee infection in elderly patients in a referral hospital in Peru.

Patients and methodsA case and control study was performed. The calculated sample was 44 cases and 132 controls. The data were collected retrospectively from clinical records. U-Mann–Whitney and Chi-square tests were performed in the comparison of cases and controls. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated in a binary logistic regression analysis to identify the risk factors, a p<.05 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) were considered significant.

ResultsSignificant (p<.05) risk factors evidenced in the bivariate analysis were obesity (OR=9.72; 95% CI: 4.47–21.14), smoking (OR=4.06; 95% CI: 1.59–10.39), rheumatoid arthritis (OR=4.66; 95% CI: 1.52–14.32), diabetes mellitus type2 (OR=5.63; 95% CI: 2.69–11.78), persistent drainage (OR=9.27; 95% CI: 3.85–22.31), superficial infection (OR=6.87; 95% CI: 3.25–14.49) and prolonged hospital stay (OR=4.67; 95% CI: 2.26–9.64). In the multivariate analysis where it was adjusted for confounding variables, it was determined that risk factors were obesity (ORa=9.14; 95% CI: 3.28–25.48), diabetes mellitus (ORa=3.77; 95% CI: 1.38–10.32), persistent drainage (ORa=4.64; 95% CI: 1.03–20.80) and superficial wound infection (ORa=27.35; 95% CI: 2.57–290.64).

ConclusionsRisk factors for prosthetic knee infection identified in this study are preventable. The main risk factors were obesity, diabetes mellitus type 2, superficial wound infection and persistent drainage, which were considered together or separately to be risk factors in the population studied.

Determinar los factores de riesgo asociados a infección de prótesis de rodilla en pacientes adultos mayores en un hospital de referencia en Perú.

Pacientes y metodologíaSe realizó un estudio de casos y controles. La muestra calculada fue de 44 casos y 132 controles. Los datos fueron obtenidos retrospectivamente de las historias clínicas. Se realizaron pruebas U de Mann Whitney y chi cuadrado para comparación de casos y controles. Se calcularon las odds ratio (OR) en un análisis de regresión logística binaria para identificar factores de riesgo. Se consideró significativa una p<0,05 y un intervalo de confianza (IC) del 95%.

ResultadosLos factores de riesgo significativos (p<0,05) en el análisis bivariado fueron la obesidad (OR=9;72; IC95%: 4,47-21,14), el tabaquismo (OR=4,06; IC95%: 1,59-10,39), la artritis reumatoide (OR=4,66; IC95%: 1,52-14,32), la diabetes mellitus tipo2 (OR=5,63; IC95%: 2,69-11,78), el drenaje persistente (OR=9,27; IC95%: 3,85-22,31), la infección superficial (OR=6,87; IC95%: 3,25-14,49) y la estancia hospitalaria prolongada (OR=4,67; IC95%: 2,26-9,64). El análisis multivariado ajustado para las posibles variables de confusión determinó que los factores de riesgo significativos (p<0,05) fueron la obesidad (ORa=9,14; IC95%: 3,28-25,48), la diabetes mellitus (ORa=3,77; IC95%: 1,38-10,32), el drenaje persistente (ORa=4,64; IC95%: 1,03-20,80) y la infección superficial de herida (ORa=27,35; IC95%: 2,57-290,64).

ConclusionesLos factores de riesgo para infección de prótesis de rodilla identificados en este estudio son prevenibles. Los principales factores de riesgo para infección de prótesis de rodilla son la obesidad, la diabetes mellitus tipo2, la infección superficial de herida operatoria y el drenaje persistente, los cuales, en conjunto o por separado, fueron considerados factores de riesgo en la población estudiada.

Thanks to quality of life improvements, the longevity of the current population has increased the use of total knee prosthesis (TKP) as part of the treatment of degenerative osteoarthritis. This surgical procedure is one of the most successful and has a high impact on the quality of life of the older adult population, evidenced by functional improvement.1–4 TKP surgery is a procedure which involves joint replacement, and is therefore considered to be major surgery. For this reason it is exposed to multiple complications, with infection being the most feared by orthopaedic surgeons as consequences are usually devastating.4 This infection has a worldwide incidence rate which varies from 1% to 2%.1,5–8 Studies report that TKP infection is the primary cause of surgical reintervention.1,6 Mortality associated with this complication ranges between 2.7% and 18%, and morbidity of this condition is associated with treatment which may cost between US$50,000 and US$100,000.5

The risk factors associated with TKP infection is a major issue to consider when planning joint replacements. Risk factors are multiple and are divided into those associated with the patient and those associated with the procedure.1,9 The factors associated with the patient include a tobacco habit,10 type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2),6 body mass index (BMI),11 depression-schizophrenia,12 heart congestive failure,13 cirrhosis of the liver,14 chronic kidney failure,3 rheumatoid arthritis,5 malignant neoplasms,15 pathology of thromboembolism,16 malnutrition,3 urinary infection,17 psoriasis16 and previous knee surgery.18 The factors associated with procedure are non use of antibiotic as prophylaxis,10 the use of postsurgical drainage,19 the use of a tourniquet,20 duration of surgery21 and transfusions.2

The behaviour of risk factors associated with the patient and the procedure is known from international literature,10 but it is important to consider that the reality of other countries may be different compared with Peru. Determining the factors associated with TKP infection will enable the orthopaedic surgeon to determine which patients require special care and which additional procedures should be taken into consideration before, during and after surgery, in order to create strategies to avoid this complication and reduce the financial health costs attached to this complication. This study could offer theoretical tools for the development of instruments9,22 to help aid prevention on a national level.

The primary aim of the study was to determine the main measures of association of risk factors to infection of knee prosthesis in older adults in a referral hospital in Peru. Secondary aims were to determine the epidemiological and demographic characteristics of the patients exposed to the risk factors and assess a group of factors which together could explain the increased risk of TKP infections.

Patients and methodsStudy designThis was an observational analytical retrospective study with a case and control design for the disease which was knee prosthesis infection. Patients operated on for TKP with a diagnosis of infection were classified as cases, based on the definition of prosthesis infection by the workgroup of Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS for its initials in Spanish) in 2011,23 subsequently updated by the Consensus of Philadelphia in 2013.24 Cases without a diagnosis of infection were classified as controls.

Selection criteriaInclusion criteria were as follows:

- –

Have diagnostic criteria of infection in patients operated on for primary prosthesis for cases, based on the workgroup of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) in 2011.23

- –

Not having diagnostic criteria of infection in patients operated on for primary prosthesis for the control groups.

- –

Patients over 65 years of age.

- –

Operated on for primary prosthesis of the knee with surgery taking place between 2012 and 2015.

- –

With postoperative follow-up over 6 months. Operated on in our national referral hospital.

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

- –

No complete medical record available.

- –

Medical record with illegible script.

- –

Bilateral prosthetic replacement surgery.

- –

Suspicion of knee prosthesis infection in studies not yet completed for diagnosis.

The sample was calculated using the programme of the Instituto del Hospital del Mar de Investigaciones Médicas (IMIM). To obtain 95% reliability and 80% statistical power, an alpha risk of .05 was accepted and an beta risk of .2 in bilateral contrast, for which reason it was necessary to have 44 cases and 132 controls to detect a minimum odds ratio (OR) of 3. A proportion of cases/control of 1/3 was used due to the low number of cases being in the hospital, as this pathology was uncommon. It was assumed that rate of exposure in the control group would be .5. Follow-up loss rate was estimated as 0%. The Poisson approximation was used.

Data collectionThe data collection tool comprised a file which included the relevant variables for the study. This information was obtained from the review of medical histories retrospectively and covered the period between 2012 and 2015 (to obtain the requested number of cases). A total of 1256 primary knee prostheses were used, according to the service statistics. Selection criteria (inclusion and exclusion) were applied and they proceeded to choose by means of a probabilistic sample, obtaining 132 controls (without infection). A non probabilistic sample of convenience was used to obtain 44 cases (with infection), with justification being the low amount of cases, and as a result all cases found were accepted. A total sample of 176 patients was obtained. Unfortunately data collection presented with several drawbacks (problems of medical record registration), and several variables such as HbA1c glycosylated haemoglobin, psoriasis and use of tourniquet had to be ruled out. The variables of anaesthesia and antibiotic prophylaxis were excluded from analysis because all patients in the sample were subjected to spinal anaesthesia and received antibiotic prophylaxis in accordance with established hospital protocols.

Statistical analysisData were processed and tabulated in the SPSS v. 23 programme. After this these data were assessed for frequencies and descriptive measurements. Bivariate analysis was subsequently performed both on the quantitative and qualitative variables. For quantitative analysis of comparison of means the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used (since the variables used did not follow any normal distribution according to the Kolomogrov–Smirnov test), whilst for the qualitative data, measurements of association using the Chi-square test were used and calculation of the OR was made with statistical significance being p<.05. Finally, multivariate analysis was performed by means of the binary logistic regression test, with the variables which were of statistical significance and which supported a model that would jointly better explain the phenomenon under study (infection). The area below the ROC curve was used to assess the degree of discrimination of the model (infected and not infected) and an area below the curve >.7 was determined to asses that the discrimination of the model was appropriate and useful.25

In this study data from medical histories were collected and a retrospective analysis was made. For this reason there were no ethical problems.

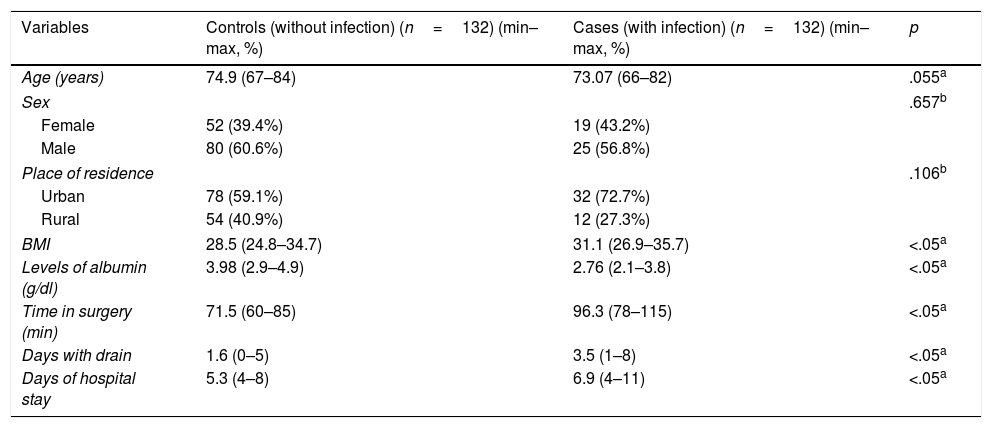

ResultsThe demographic characteristics of this population and the results of analysis of other numerical variables are shown in Table 1.

Demographic characteristic of elderly adult patients and numeric variables found in the study population.

| Variables | Controls (without infection) (n=132) (min–max, %) | Cases (with infection) (n=132) (min–max, %) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 74.9 (67–84) | 73.07 (66–82) | .055a |

| Sex | .657b | ||

| Female | 52 (39.4%) | 19 (43.2%) | |

| Male | 80 (60.6%) | 25 (56.8%) | |

| Place of residence | .106b | ||

| Urban | 78 (59.1%) | 32 (72.7%) | |

| Rural | 54 (40.9%) | 12 (27.3%) | |

| BMI | 28.5 (24.8–34.7) | 31.1 (26.9–35.7) | <.05a |

| Levels of albumin (g/dl) | 3.98 (2.9–4.9) | 2.76 (2.1–3.8) | <.05a |

| Time in surgery (min) | 71.5 (60–85) | 96.3 (78–115) | <.05a |

| Days with drain | 1.6 (0–5) | 3.5 (1–8) | <.05a |

| Days of hospital stay | 5.3 (4–8) | 6.9 (4–11) | <.05a |

BMI: body mass index; max: maximum; min: minimum.

Analysis of the qualitative variables showed that 60.6% and 56.8% of control group patients and infection group patients, respectively, were male, with the difference between sexes not being significant regarding the risk of infection (p=.657). Regarding place of origin, it was observed that 59.1% and 72.7% of control group patients and infection group patients, respectively, were from urban areas, with the difference between patients from the rural and urban areas not being significant regarding risk of infection (p=.106).

Analysis of the quantitative variables showed that the mean age of control group patients was74.9years (min–max: 67–84years), in contrast to the infection group, where the mean was 73.07years (min–max: 66–82); no significant differences were found when comparing these means (p=.055). Regarding BMI, it was observed that the control group patients presented with a mean of 28.5 (min–max: 24.8–34.7) compared with the infection group, with a mean of 31.1 (min–max: 26.9–35.7). The albumin level mean was 3.98g/dl (min–max: 2.9–4.9) in the control group, in contrast to the infection group where the mean was 2.76g/dl (min–max: 2.1–3.8). Time in surgery was a mean of 71.5min (min–max: 60–85) in the control group, in contrast to the infection group where a time of 96.3min (min–max: 78–115) was recorded. The variable number of days with wound drainage had a mean of 1.6days (min–max: 0–5) in the control group and in the infection group this was 3.5days (min–max: 1–8). Regarding number of hospital stay days, the mean control group mean was 5.3days (min–max: 4–8), compared with the infection group mean of 6.9days (min–max: 4–11). It is important to mention that these last variables mentioned (BMI: p=.00084; albumin levels: p=.00089; time in surgery: p=.00022; number of days of drainage: p=.00042, and number of hospital stay days: p=.00052) were significantly different (p<.05) in mean comparisons.

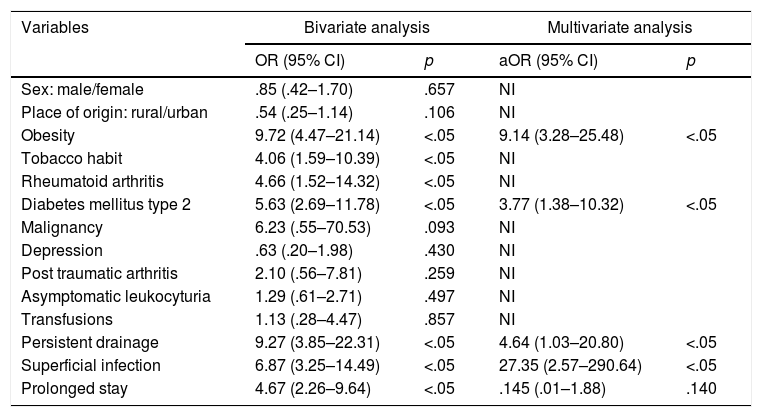

In bivariate analysis of qualitative variables the Chi-square test was performed and the OR was obtained with a confidence interval (CI) of 95%. The analysis obtained statistical significance (p<.05) when the infection was associated with obesity (OR=9.72; 95% CI: 4.47–21.14), tobacco habit (OR=4.06; 95% CI: 1.59–10.39), rheumatoid arthritis (OR=4.66; 95% CI: 1.52–14.32), DM2 (OR=5.36; 95% CI: 2.69–11.78), persistent drainage (OR=9.27; 95% CI: 3.85–22.31), superficial infection (OR=6.87; 95% CI: 3.25–14.49) and prolonged stay (OR=4.67; 95% CI: 2.26–9.64). Non significant results were obtained (p>.05) in variables such as gender (OR=.85; 95% CI: .42–1.70), place of origin (OR=.54; 95% CI: .25–1.14), presence of neoplasm (OR=6.23; 95% CI: .55–70.53), depression (OR=.63; 95% CI: .20–1.98), post traumatic arthritis (OR=2.10; 95% CI: .56–7.81), asymptomatic leukocyturia (OR=1.29; 95% CI: .61–2.71) and transfusions (OR=1.13; 95% CI: .28–4.47).

With regard to the multivariate analysis, a model using variables with the highest OR was used and with statistical significance (p<.05), such as obesity, DM2, persistent drainage, superficial infection and prolonged stay. These five variables were chosen with the highest strength of association (OR) since the multivariate analysis had recommendations for its usage, one of them being not to select more than one variable for each ten individuals with the effect of studying (knee prosthesis infection) what they wish to model.25 The values of obesity (ORa=9.14; 95% CI: 3.28–25.48), DM2 (ORa=3.77; 95% CI: 1.38–10.32), persistent drainage (ORa=4.64; 95% CI: 1.03–20.80) and superficial infection (ORa=27.35; 95% CI: 2.57–290.64) were found. Only one of these variables was not statistically significant (p<.05): prolonged stay (ORa=.145; 95% CI: .01–1.88). The area below the ROC curve for assessing the degree of discrimination of the model (infected and not infected) found a value of .83 (95% CI: .76–.9), for which discrimination of the model is appropriate. Variables such as a tobacco habit and rheumatoid arthritis were not used, since they did not contribute to the model, despite the fact they were statistically significant. The variables of sex and age were not used, since there were no significant differences in their respective analyses.

DiscussionPrevious studies carried out showed the different risk factors associated with knee prosthesis infection with difference levels of association.1–4,8,9,13,15,16,22 One study of cases and controls from a Spanish population sample analysed risk factors in patients with knee prosthesis infection with similar variables to this present study (age, sex, obesity, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, duration of surgery, transfusions, persistent drainage, skin infections), and presented statistical significance (p<.05) in duration of surgery, persistent drainage and skin infections.26

Preoperative factorsAge was not a risk factor associated with knee prosthesis infection compared with the control group. Previous studies had contradictory results regarding the fact that if age was >65 years it was a risk factor: some studies obtained significant findings,13,16 whilst others did not,3,15,26 and controversy therefore remains.

There was a predominance of the male sex both in the control group (60.6%) and in the group with infection (56.8%). In our study there were no significant differences in both groups, with this study being very similar to the one with the Spanish population.26 In contrast, other research studies found there was a higher risk of infection in the male sex (OR=1.36–1.89).1,15 It is important to mention that the pH and thickness of the skin, characteristics of sebaceous induction and the distribution of fat are different in both sexes, and these characteristics may make the male sex more susceptible to the infection.27

Regarding place of residence, living in a rural area was not more common and was not considered a risk factor. Two studies reviewed found statistical significance in relation to residing in rural areas, one of them as a risk factor (OR=2.63)13 and the other as a protective factor (RR=.77).15 Economic status is a factor of complex association to knee prosthesis infection, because patients of lower economic status have low nutritional diets and suboptimal care, which may affect infection.28

BMI values determined that the obesity variable (BMI≥30) is a significant risk factor for infection, with an OR=9.72. A high value was observed compared with the OR found in other reviewed studies,1–3,13,15,26 which had OR ranges=1.47–4. One study demonstrated an OR=18.5 for morbid obesity (BMI>50).9 The increase in adipose tissue could predispose a tension on the surgical wound, the formation of seromas and lead to persistent drainage. For an obese patient it is necessary to make large incisions for better exposure of the surgical field, which raises the risk of infection.4

Albumin levels in the infection group (2.76g/dl) had an average value below the normal value (NV: 3.5–5g/dl) and presented with significant differences compared with the control group. No study was found which assessed the levels of albumin, but it is important to mention that low levels are a sign of malnutrition. The problems relating to wound closure are more commonly seen in patients with preoperative nutritional depletion. Malnutrition is related to persistent drainage of the surgical wound.27

Regarding tobacco habits, significant OR values were found for the appearance of infection of the knee prosthesis (OR=4.06). Two studies were reviewed relating to this variable, and both found there was a significant association as risk factors for infection of the knee prosthesis, but both with extreme values. One was a systematic review, which found an OR value of 12.76,9 and the other obtained an OR value of 1.83.15 A tobacco habit is a theoretically demonstrated risk factor, since it may reduces perfusion, generate areas of hypoxia, change the function of the neutrophils and lead to a lowering of defences against microorganisms.29

A significant association was found for rheumatoid arthritis as a risk factor for knee prosthesis infection, with an OR=4.66. Three studies assessed found values of OR lower than those found in our study. The first was a systematic review, and found there were OR values=1.70.15 The second we a case and control study and found OR values of .50.4 The third found OR values of 1.83.3 One study conducted in a sample in Spain and did not find any significant association between the risk of knee prosthesis infection and rheumatoid arthritis.26 Rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of knee prosthesis infection due to its relationship with immunosuppressant therapy, but its mechanism is as yet unlear.5

Uncontrolled DM2 is included in several studies as a risk for knee prosthesis infection.1,3,9,13,15,16 in this study we found there was a significant association between DM2 and knee prosthesis infection, with OR values of 5.63. The ranges of OR in the studies assessed had a range of OR=1.28–6.07, which is consistent with that found. Diabetic patients had an increased risk of infection, since the microvascular lesion could lead to hypoxia at the surgical wound level. The prevalence of infectious complications in knee arthroplasties in patients with diabetes varied between 1.2% and 12%.27

Malignant neoplasm, depression, post traumatic arthritis and asymptomatic leukocyturia had no significant association with the appearance of knee prosthesis infection (Table 2). The study conducted was concordant with a systematic review which demonstrated that malignant neoplasm had no significant relationship with the appearance of knee prosthesis infection (RR=1.52; 95% CI: .98–2.34).15 Malignant neoplasms are related to the lowered immunity. Depression as a risk factor is physiopathologically linked to malnutrition and for this reason is a risk factor which has an apparent probability of knee prosthesis infection.27 One case and control study found there was a significant association between the presence of post traumatic arthritis and infection, finding significant values of hazard ratio (HR=3.58; 95% CI: 2.20–5.82). This finding is contrary to our study. Surgical scarring could contribute to the risk of knee prosthesis infection but postosteotomy and post arthroscopy of the knee patients did not report the same relationship.26,27 A retrospective study demonstrated that there was no significant association between asymptomatic leukocyturia and the appearance of knee prosthesis infection (OR=1.04; 95% CI: .13–7.83).30 one study conducted on a sample in Spain showed that no cases of knee prosthesis infection had been found in patients with asymptomatic leukocyturia.31

Risk factors associated with infection of total primary knee arthroplasty in elderly adult patients.

| Variables | Bivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | aOR (95% CI) | p | |

| Sex: male/female | .85 (.42–1.70) | .657 | NI | |

| Place of origin: rural/urban | .54 (.25–1.14) | .106 | NI | |

| Obesity | 9.72 (4.47–21.14) | <.05 | 9.14 (3.28–25.48) | <.05 |

| Tobacco habit | 4.06 (1.59–10.39) | <.05 | NI | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 4.66 (1.52–14.32) | <.05 | NI | |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 5.63 (2.69–11.78) | <.05 | 3.77 (1.38–10.32) | <.05 |

| Malignancy | 6.23 (.55–70.53) | .093 | NI | |

| Depression | .63 (.20–1.98) | .430 | NI | |

| Post traumatic arthritis | 2.10 (.56–7.81) | .259 | NI | |

| Asymptomatic leukocyturia | 1.29 (.61–2.71) | .497 | NI | |

| Transfusions | 1.13 (.28–4.47) | .857 | NI | |

| Persistent drainage | 9.27 (3.85–22.31) | <.05 | 4.64 (1.03–20.80) | <.05 |

| Superficial infection | 6.87 (3.25–14.49) | <.05 | 27.35 (2.57–290.64) | <.05 |

| Prolonged stay | 4.67 (2.26–9.64) | <.05 | .145 (.01–1.88) | .140 |

NI: variables not included in the multivariate analysis; OR: odds ratio; aOR: adjusted odds ratio.

Significant differences were found in the mean of operating time between the control group and the group with infection: patients who developed infection were in the operating theatre for a longer amount of time in the analysed sample. Previous studies reveal contradictory results relating to time in surgery; some show there was no statistical significance in relation to the increase in time for developing knee prosthesis infection,4,16,32 in contrast to others where there was.1,9,24,26 An approximate time of >2h has been described in the literature as the cut-off point for risk of infection.27 The more time a surgical procedure is delayed, the greater the possibility of the contaminating agents having greater contact with the surgical site.24

Blood transfusion did not reveal any significant association with the appearance of knee prosthesis infection. These results were concordant with the reviewed studies.3,4,16,26 Allergenic blood transfusion generates an immunomodulating reaction which could be associated with knee prosthesis infection, but transfusions have been associated with an increase in the probability of haematomas and persistent drainage.27

Postoperative factorsRegarding the days of persistent drainage variable, a significant increase was observed in the group which developed infection when the means were compared. The persistent drainage variable, defined by the consensus of Philadelphia as the drainage through the wound which persists for more than 72h,24 had an OR=9.27, which was statistically significant in relation to the knee prosthesis infection. A study conducted in a sample in Spain showed there was a significant association between persistent secretion and knee prosthesis infection, but the OR could not be calculated.26 Persistent drainage increases hospital stay according to that reported in the literature.27

Superficial infection of the surgical wound was assessed based on characteristics such as dehiscence, erythema and necrosis around wound edges. In this study a significant association was made between the appearance of superficial infection and the presence of knee prosthesis infection, with an OR=6.87. One study of a sample in Spain shows OR values=11.75, with significant association between skin infections and infection of knee prosthesis.26 The literature showed that the superficial infections of the wound raise the risk of prosthesis infection by four within the first five years after insertion of it.27

Patients with infection presented with a higher hospital stay, expressed in days. When the prolonged stay variable was analysed (defined by our study as >5 days) with the risk of infection, an OR was found to be=4.67. This finding was in keeping with one of the reviewed studies, where a lower OR value was found (OR=1.09; 95% CI: 1.01–1.10).2 The intrahospital pathogens to which the patients had been exposed were the potential agents of infection.

For the multivariate analysis (binary logistic regression) five variables were chosen with higher powers of association (OR). The variables of obesity (ORa=9.14), DM2 (ORa=3.77), persistent drainage (ORa=4.64) and superficial infection (ORa=27.35) were significant, but the prolonged stay variable (ORa=.145) was not. This allowed us to specify that obesity, DM2, persistent drainage and superficial infection were the risk factors which jointly better explained the appearance of a knee prosthesis infection. Previous studies made additional comparison using the multivariate analysis. One of them did not find any significant risk factor associated with knee prosthesis infection.22 Another similar study showed two variables which when combined formed a model to explain the appearance of infection, and these were use of drainage (OR=7; 95% CI: 2.1–25; p<.05) and high INR (OR=2.4; 95% CI: 1.1–5.7; p<.05),8 with variables being different from those found in research.

The limitations of this study are directly related to the deficit of an appropriate database and difficult access to it, since several variables were lost during the study due to poor recording. In addition, the amount of the sample of prosthesis infection cases had to be adjusted with the calculator due to the prevalence of this pathology being very scarce, for which it is suggested that a sample with a higher number of cases be carried out. No national literature has been found that describes and develops similar research problems to this one nor compares the association of prosthesis infection to serum albumin levels.

ConclusionsFrom this study we may conclude that the identified preoperative risk factors for knee prosthesis infection are obesity and DM2, whilst postoperative risk factors are superficial infection of the surgical wound and persistent drainage. These were separately and jointly considered to be the main risk factors.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III, case study and controls.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific financing from any public sector, trade sector or non profit making entities.

Conflict of interestsNone.

The authors wish to thank the Knee Unit of the Hospital Rebagliati for its support regarding data.

Please cite this article as: Palacios-Flores MA, Alfaro-Fernandez PR, Gutarra-Vilchez RB, Suarez-Peña R. Factores asociados a infección de prótesis total de rodilla primaria en adultos mayores en un hospital de referencia en Perú. 2012-2015. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2020;64:191–198.