Tarsal coalition has an incidence between 2%–5% of the general population, and calcaneonavicular is the most frequent (53%). When conservative treatment fails, surgical resection must be indicated. Endoscopic resection is a less invasive technique and can be considered an alternative with better functional recovery.

Material and methodsWe performed a retrospective study of the patients with calcaneonavicular coalition operated in our hospital between 2015 and 2018. We performed an endoscopic resection. We used AOFAS scale score for the results.

ResultsWe reviewed seven cases for a minimum of 12 months. AOFAS score improved from 42 before surgery to 92. There were no major complications from surgery. We had a patient with dysesthesias in the forefoot that improved at 3 months and a case of local swelling that solved with ice and rest.

ConclusionsEndoscopic resection has advantages over open surgery. Offers a great vision and good control of the coalition resection, provides an early rehabilitation, decrease hospital stay, improves cosmetic results and the probability of neuroma is minimum with an adequate control of the technique.

Las coaliciones tarsianas tienen una incidencia global en la población entre el 2 y el 5%. La coalición calcáneo-navicular representa el 53% de ellas. El tratamiento inicial debe ser conservador, quedando relegada la cirugía al fracaso de éste. Como alternativa al tratamiento quirúrgico convencional se ha descrito la resección endoscópica, que supone una técnica con menor agresividad y más rápida recuperación funcional.

Material y métodosRealizamos un estudio retrospectivo de todos los pacientes con coalición calcáneo-navicular intervenidos quirúrgicamente en nuestro hospital mediante resección endoscópica durante los años 2015 al 2018. Para la valoración de resultados se usó la escala AOFAS de pie y tobillo.

ResultadosSe revisaron siete pies durante un periodo mínimo de 12 meses. La escala AOFAS preoperatoria era de 42 y de 92 en la última revisión clínica. No hubo complicaciones mayores derivadas de la cirugía. Tuvimos un caso de disestesias en el dorso de pie que se resolvió al tercer mes de evolución y un paciente con tumefacción local que se solucionó con hielo y pie elevado.

ConclusionesLa resección endoscópica ofrece ciertas ventajas sobre la cirugía abierta convencional. Ofrece una visión óptima de las estructuras anatómicas y un buen control de la resección de la barra. Permite una rehabilitación precoz, la estancia hospitalaria disminuye, los efectos cosméticos se minimizan y la probabilidad de neuromas es prácticamente nula con un buen control de la técnica.

Tarsal coalition has an overall incidence in the population of between 2% and 5%, more than half being bilateral. The most frequent are calcaneonavicular coalition (CNC) and talocalcaneal coalition (TCC), which account for 53% and 37% respectively.1–3 They are the cause of valgus flat foot not reducible on forefoot. Symptoms start around the age of 10, when the coalition begins to ossify causing stiffness and pain. Patients usually report repetitive ankle sprains and in the long term can result in instability of the ankle and/or joint degeneration. Initial treatment should be conservative for a minimum of six months, with surgical treatment reserved for when this fails.

Surgical treatment of CNC consists of resection of the coalition and in most cases is usually combined with soft tissue interposition to reduce recurrence. The most common complications of conventional open surgery are infection, neuroma and stiffness.4 Endoscopic resection has been described as an alternative and to minimise these complications, a minimally invasive technique that is less surgically aggressive and with faster clinical recovery.5 When there is considerable heel valgus, combining with the implantation of a stent in the tarsal sinus is recommended or calcaneal osteotomy, depending on the patient’s age.

The objective of this paper is to describe the surgical technique and present the clinical outcomes of our series comparing them with those published in the literature.

Material and methodsWe performed a retrospective study of all patients undergoing calcaneonavicular coalition surgery performed endoscopically in our hospital from 2015 to 2018. The inclusion criteria were persistence of symptoms (pain, repetitive sprains and stiffness) and limitations to daily activities after conservative treatment for at least six months. Epidemiological variables such as age and sex were collected. For the evaluation of results, the AOFAS foot and ankle scale was used preoperatively and at last follow-up. Patients were followed-up for at least 12 months.

The diagnosis was confirmed with oblique, weight-bearing X-rays of both feet, CT and MRI, necessary to assess the extension of the coalition and whether it was bony or fibrocartilaginous (Fig. 1). In all cases, an isolated endoscopic resection of the coalition was performed, with a 4 mm and 30° optic, with no additional surgical procedure (calcaneal osteotomy, tarsal sinus implant, or interposition of soft parts) since none of the patients had excessive hindfoot valgus.

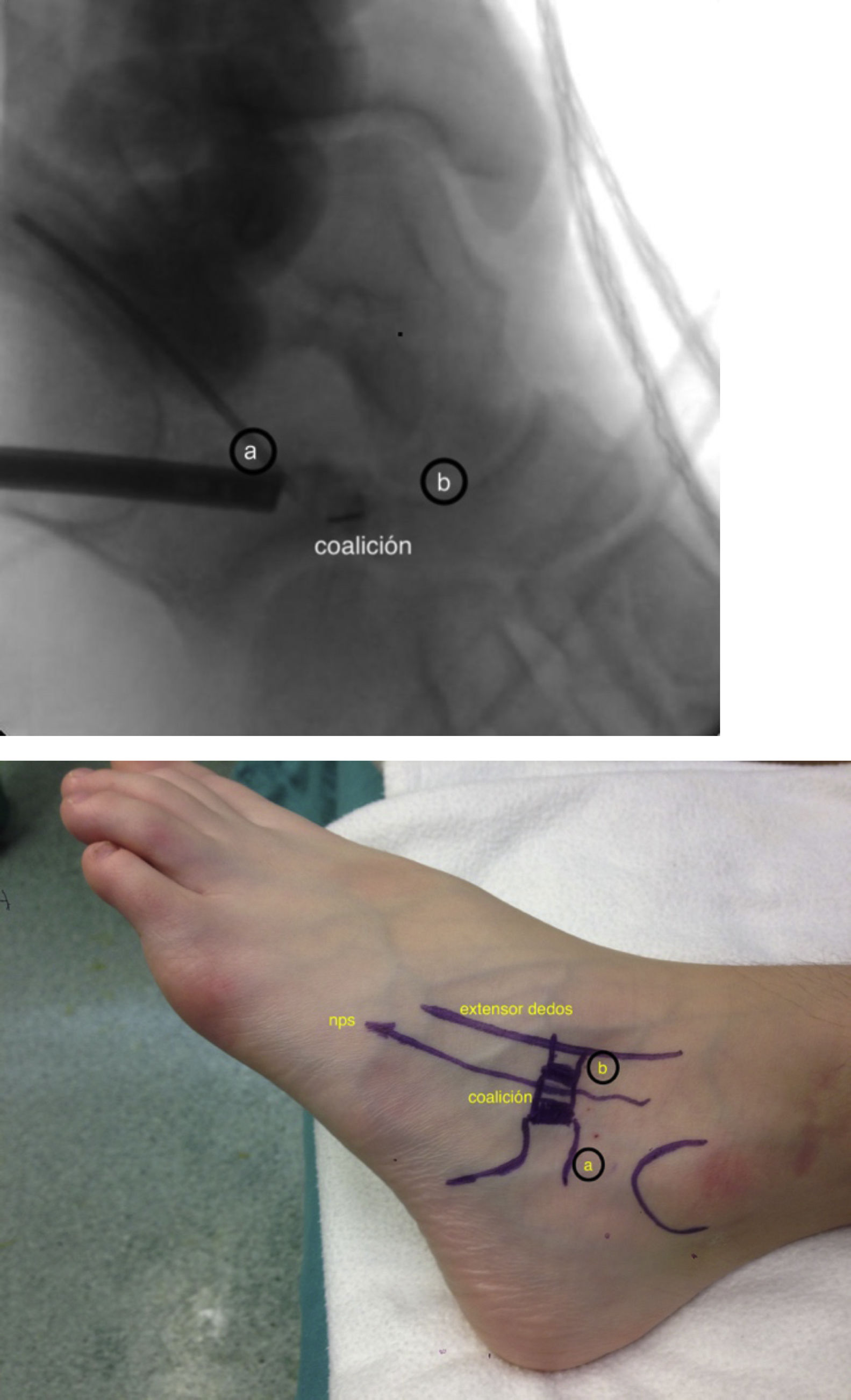

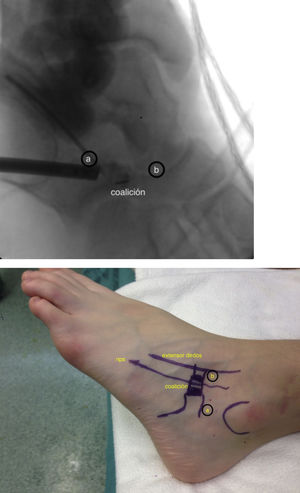

Surgical techniqueThe patient is placed in a supine position, with ischaemia at the root of the thigh and sac under the ipsilateral buttock to confer internal rotation to the limb. By palpation, the peroneal malleolus, the extensor tendons of the toes and the cutaneous branch of the superficial peroneal nerve are delimited, which becomes visible when performing plantar flexion of the fourth toe. Under endoscopy, the area of fusion is located, which extends from the anterior calcaneal tuberosity to the navicular. The viewing portal is posterior to the area of coalition and located on the tarsal sinus. The second portal is the working portal and is over the coalition, medial to the superficial peroneal nerve and lateral to the extensor tendons of the toes (Fig. 2).

After inserting the arthroscope into the viewing portal, we proceed to the tarsal sinus. We then make the working portal and with straight mosquito forceps dissect the subcutaneous tissue over the coalition, heading towards the tarsal sinus until we locate the optic camera. Alternatively, with a synoviotome and a vaporiser, we go upwards from the tarsal sinus through the anterior calcaneal tuberosity, delineating the coalition until we reach the body of the navicular. We perform the resection with an electric bone drill of 5 mm. When starting the resection, the joint between the talar head and the navicular appears and from there we progress in depth to resect the entire coalition until confirming that the navicular and calcaneus move independently. The joint between the calcaneus and cuboid is exposed and between the astralagus and navicular on the other side.

We consider the resection complete when the bone drill passes freely, which assures us that we have left a minimum space of 10 mm between each. Inversion and eversion of the foot allows us to assess mobility and check that there is no bone impingement. Intraoperative radioscopy confirms that the resection has been sufficient before concluding the surgery (Fig. 3). The surgical portals are closed with two monofilament stitches. After surgery, a compression bandage is applied, and local ice is applied. The bandage is removed after seven days and active and passive mobility is stimulated, as well as progressive weight-bearing as tolerated.

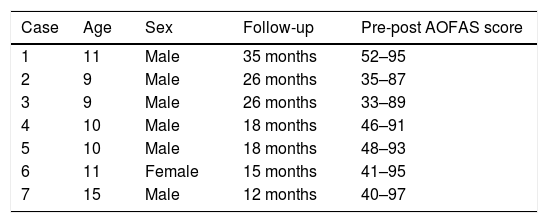

ResultsA total of five patients (four men and one woman) with CNC were operated. The coalition was bilateral in two of the patients and both feet were operated in the same surgical session. The average age was 11.2 years. We finally followed-up a total of seven feet for a minimum of 12 months and until they were asymptomatic and discharged (Table 1). All the patients underwent the surgical technique described.

The mean preoperative AOFAS score was 42, reflecting absence of mobility of the hindfoot on inversion or eversion, mild or moderate pain, difficulty in undertaking recreational activities, and difficulty walking on uneven ground. There were no cases with impaired alignment of the hindfoot that required correction. At final follow-up, all the parameters evaluated had improved. The mean preoperative AOFAS score was 42 and a mean score of 92 at the end of follow-up was obtained due to disappearance of pain and return to sports activities without limitation. Both the patients and families were satisfied with the outcome.

There were no major complications following the surgery in terms of infection, neurovascular or tendon injury. We had one case of dysaesthesia in the dorsum of the foot that resolved after the third month and one patient with local swelling that resolved with ice and elevated foot.

DiscussionOnce we evaluated our results, endoscopic resection of calcaneonavicular coalition was shown to be a safe alternative to conventional open resection, presenting low morbidity, without major complications and with good vision to establish that complete resection. In our series all the patients were of paediatric age and presented fibrocartilaginous coalitions that were not fully ossified. Surgical treatment of CNC is indicated when adequate conservative treatment has failed for a minimum of six months.6

Bagdley7 first described CNC resection for the treatment of painful flatfoot in 1927. Later in 1930, Bentzon8 added the interposition of the short extensor muscle of the toes as a surgical procedure to reduce coalition relapse rates. With the same aim other authors interposed autologous fat tissue.9 The literature review shows that in the series in which tissue interposition was not performed, there was radiological recurrence of the coalition in between 25% and 50% of the cases, whereas when interposition of the short flexor muscle of the toes was performed, recurrences were lower than 25%.10 In a paper by Moyes et al.11 two groups were revised with isolated CNC resection or muscle interposition and they observed recurrences of 40% in the former group and none in the 10 cases with interposition. On the other hand, muscle interposition entails immobilisation with a splint for a minimum of 4–6 weeks and some authors advise postponing weight-bearing for 8 or 10 weeks.12

Endoscopic resection without interposition in these cases allows immediate mobilisation and early weight-bearing. Both factors seem to be a positive influence in that we found no recurrence of the coalition in our series. There were no cases of joint surface deterioration adjacent to the coalition, and therefore bar resection enabled correct postoperative mobility.

Another common complication with open surgery is the presence of superficial peroneal nerve neuromas that can cause permanent dysaesthesia and poor outcomes.13 In this regard, Molano-Bernardino et al.14 in 2009 conducted an interesting experimental study on cadavers in an attempt to locate arthroscopic portals that would provide surgical safety by minimising iatrogeny. In the endoscopic technique described in our paper, the portals are made at a minimum distance of 1 cm on each side of the nerve and the dissection is performed in depth to the nerve. This is why we had only one case of dysaesthesia in the dorsum of the foot that resolved spontaneously.

Open surgery involves difficulty in ensuring correct resection of the plantar area of the coalition,15–17 while with arthroscopy the calcaneocuboid and talonavicular joint are correctly visualised at all times, and resection in depth is monitored until it is confirmed that the most plantar zone has been reached and a minimum space of 5 mm has been left. It is advisable to leave a distance of a minimum of 10 mm between calcaneus and navicular to avoid impingement between both coalition bones on inversion and eversion movements.18,19

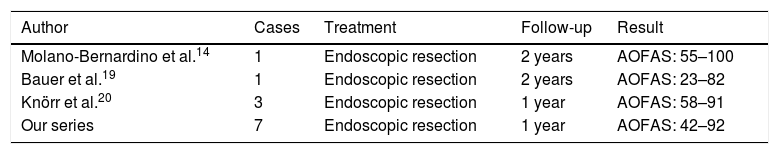

Finally, we reviewed the literature to compare the results obtained with those previously published by other authors who have performed endoscopic resection of the CNC (Table 2). The published series refer to isolated cases and only Knörr et al.20 and Singh and Parsons21 present series of three patients. Our series of seven cases is the longest published to date. A final AOFAS score of more than 90 points concurs with the results presented by most authors and also indicates that endoscopic resection is a technique that allows great clinical and functional improvements with little postoperative morbidity.22,23

We must highlight as limitations of our study that it is retrospective with a small sample size. The latter is conditioned by the fact that surgery was only performed in the cases where symptoms of pain and functional disability had persisted after a minimum period of conservative treatment of 6 months.

Regarding the technique, it should be noted that radioscopy should be used in the operating theatre initially to locate the coalition and reference points of the portals, and radiological control is advisable before finishing the surgery to confirm that the resection has been sufficient. The surgeon must have a good anatomical knowledge of the working area and previous control of the arthroscopic surgery technique. All this facilitates the learning curve required and minimises any possible iatrogeny.

ConclusionsEndoscopic resection of the CNC offers certain advantages over conventional open surgery. It allows optimal vision of the anatomical structures and good control of the bar resection to confirm that we have reached the plantar area, which is the most difficult to access using the open technique.

In the postoperative period, early rehabilitation is permitted, without the need for immobilisation, and weight-bearing is allowed as tolerated. Hospital stay is reduced or is not necessary. The cosmetic effects are minimised by avoiding a scar on the dorsum of the foot and the likelihood of neuroma is practically nil with good control of the technique.

Studies with a greater number of cases are needed to confirm this technique as a solid treatment alternative. Long-term follow-up of these patients will confirm that the coalition does not recur.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence 4: Case series.

Ethical responsibilitiesThe authors declare that no animal testing has been performed. They also declare that the research study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Faubel Navarrete E, Sánchez-González M, Vicent V, Puchol E. Resección endoscópica de la coalición calcaneonavicular. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2020;64:375–379.