Symptomatic cobalt toxicity from a failed total hip replacement is a rare, but devastating complication. Potential clinical findings include cardiomyopathy, hypothyroidism, skin rash, visual and hearing impairment, polycythaemia, weakness, fatigue, cognitive impairment, and neuropathy. The case is presented of a 74 year-old man in whom, after a ceramic–ceramic replacement and two episodes of prosthetic dislocation, it was decided to replace it with a polyethylene–metal total hip arthroplasty (THA). At 6 months after the revision he developed symptoms of cobalt toxicity, confirmed by analytical determination (serum cobalt level=651.2μg/L). After removal of the prosthesis, the levels of chromium and cobalt in blood and urine returned to normal, with the patient currently being asymptomatic. It is recommended to use a new ceramic on ceramic bearing at revision, in order to minimise the risk of wear-related cobalt toxicity following breakage of ceramic components.

La intoxicación por cobalto después de la revisión de una artroplastia total de cadera es poco común, pero una complicación potencialmente devastadora. Los síntomas incluyen: cardiomiopatía, hipotiroidismo, erupciones en la piel, alteraciones visuales, cambios en la audición, policitemia, debilidad, fatiga, deterioro cognitivo y neuropatía. Presentamos el caso de un varón de 74años que tras recambio a par cerámica-cerámica y dos episodios de luxación protésica se decidió nuevo recambio a par polietileno-metal. A los 6meses de la reintervención comenzó con clínica de intoxicación por cobalto, confirmada mediante determinación analítica, presentando niveles pico de cobalto en suero de 651,2μg/l. Tras retirada protésica y reimplante, se normalizaron los niveles de cromo y cobalto en sangre y orina, encontrándose el paciente actualmente asintomático. Recomendamos el uso de pares cerámica-cerámica en las cirugías de revisión de cadera tras rotura de componentes cerámicos para reducir al mínimo el riesgo de toxicidad por cobalto.

Ceramic-on-ceramic bearings used in total hip replacement were first developed in the seventies in the hope that ceramic's low incidence of wear would reduce the rates of revision surgery.1,2 Unfortunately, ceramic components can fracture due to their fragility and low elasticity coefficient.3 Failure of the ceramic femoral head component is most common after a traumatic event, whereas acetabular inserts commonly fail where there is no history of trauma.4

Recent manufacturer's data (CeramTec GmbH, Plochingen, Germany) show a significant reduction in the rate of fractures of fourth generation Biolox Delta ceramic heads (0.002%) compared to third generation ceramic heads (0.021%).5 The fracture rates of third and fourth generation ceramic liners have remained relatively constant at 0.032% and 0.028%, respectively.5 When revision component options are discussed after a catastrophic failure, patients are often reluctant to accept another ceramic device for fear of a further fracture of the component. This is one reason, amongst others, that polyethylene metal is often chosen in conjunction with synovectomy to mitigate the amount of residual ceramic particles and thus avoid increased rates of wear. However, it has been demonstrated that reliably removing all ceramic debris without extensive anterior dissection and subsequent synovectomy is extremely difficult.6 These residual particles incorporated in polyethylene rapidly increase the rates of wear on the prosthetic head and expose the patient to the toxic effects of heavy metals.

We present the case of a 74-year-old man presenting symptoms of cobalt toxicity after change of a total hip replacement prosthesis with a fractured ceramic-on-ceramic bearing to a polyethylene-metal total hip arthroplasty. At the time of the initial revision surgery it was found that the ceramic head was fractured and the acetabular lining was intact. Our aim is to show the patient's clinical progress, determine the clinical features of cobalt toxicity, discuss the radiological and intraoperative findings, and finally to review the recommendations for the management and prevention of this complication.

Clinical caseA 74-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes, physically active, who had undergone a total hip arthroplasty with a ceramic-on-ceramic bearing in 2004: Duofit cup (SAMO, Bologna, Italy), Bioceramic head (SAMO, Bologna, Italy), F2L stem (Lima-Lto, Udine, Italy). He had resumed his usual daily activities, when in 2010 during a game of racquetball he felt a crack and was taken to the emergency department. X-ray showed prosthetic luxation with fracture of ceramic head. The patient was operated and the Biolox-forte (Lima-Lto, Udine, Italy) ceramic head was changed. It was decided not to remove the remaining prosthetic components that were well implanted. Ten days after the operation the patient suffered another episode of luxation after getting up from his sofa at home. He was admitted to the emergency department and the prosthesis was reduced under sedation. A CAT scan was performed which showed the correct alignment of the prosthetic components, and the patient was discharged from hospital with anti-luxation control measures. One month after the reduction he suffered a further episode of prosthetic luxation, and was admitted for revision surgery: removal of cup, a new Delta TT titanium cup (Lima-Lto, Udine, Italy) was impacted and a polyethylene anti-luxation insert was placed, Delta Cup-UHMWPE X (Lima-Lto, Udine, Italy). The surgeon decided not to change the stem which was stable, and to achieve better stability of the prosthesis decided to place an extra long metal CRCrMo head (Lima-Lto, Udine, Italy). After appropriate radiographic control, the patient was discharged and given an outpatient appointment for follow-up.

At 12 months after the operation the patient reported increasingly constant and debilitating pain. He also presented asthenia, general malaise with weight loss of 10kg, sallow complexion, choluria, urticaria, neuropathic pain (meralgia paresthetica), hypothyroidism that had started a month previously, and hearing loss.

The analytic study showed CRP: 20.7, neutrophilia (76.5%) with no leukocytosis and eosinophilia (12.3%).

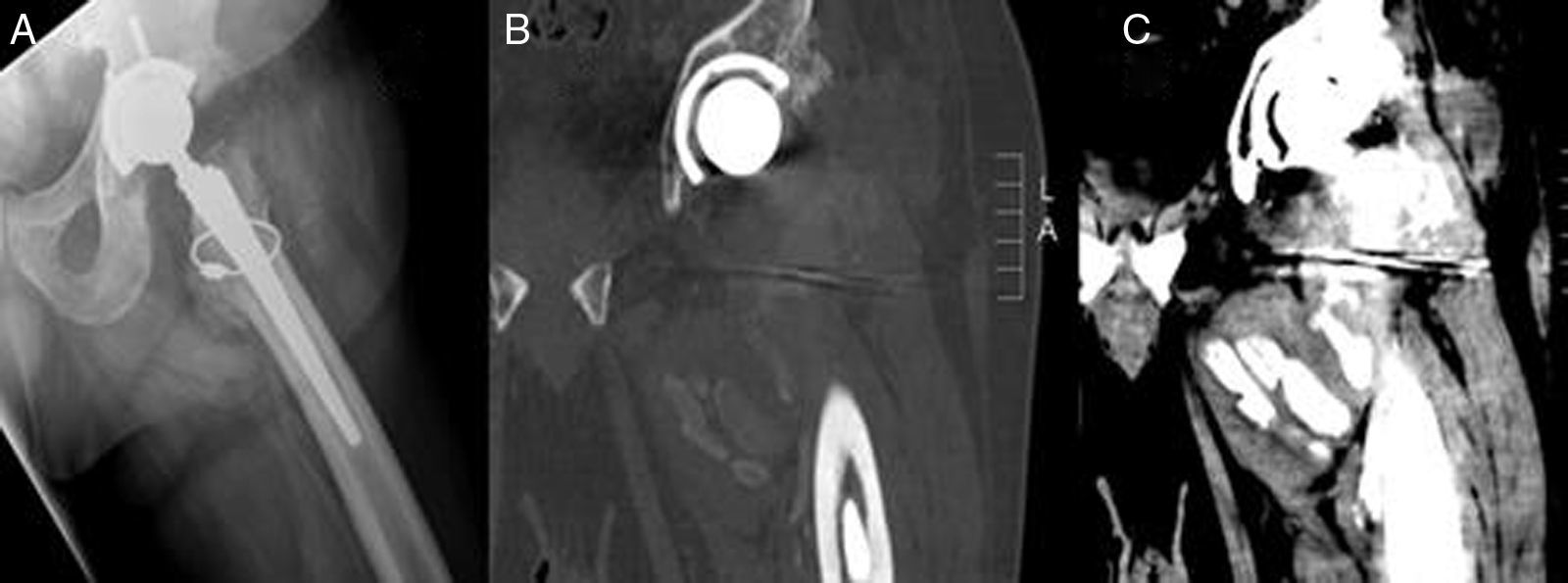

Plain X-ray revealed peri-articular calcifications and reduced radiographic density which was interpreted as the presence of liquid content in the joint. CAT scan revealed heterotopic calcifications in an intra- and extra-capsular location with involvement of all the periprosthetic muscle groups and no signs of loosening (Fig. 1).

Hard metal disease was suspected clinically, tests were requested to determine blood and urine chromium and cobalt levels, revealing a urinary chromium level of 119μg/l (normal up to 25μg/l), a serum chromium level of 55.7μg/l (normal up to 15μg/l), a serum cobalt level of 651.2μg/l (normal up to 10μg/l), a urinary cobalt level of 2.326μg/l (normal up to 15μg/l), and a diagnosis was made of heavy metal poisoning.

A surgical revision was undertaken and a dense liquid collection was found, inky in appearance, at joint level and around the implant, affecting the bone-prosthesis interface. Black incrustations could be seen in the polyethylene insert and damage at the level of the acetabular cup. It was impossible to remove the modular neck, which was scraped (Fig. 2). It was decided to remove the entire implant, thoroughly clean and resect the infiltrated tissue (synovectomy), and samples were sent to anatomic pathology.

(A) Periarticular collection stained with metal particles; (B) large infiltration of periarticular tissue by metal particles; (C) infiltration of polyethylene insert by metal particles; (D) abrasion of the surface of the metal head with loss of polish; (E) appearance of the extracted stem with calcifications around it.

The patient was kept in Girdlestone until the chromium and cobalt levels reduced, the gradual decrease in their levels was checked (Fig. 3) in a series of tests as well as the reduction in the associated symptoms. Given the patient's improved clinical and analytical picture it was decided that a new revision prosthesis should be implanted (Lima-Lto, Udine, Italy) with Biolox-Delta ceramic bearing (Lima-Lto, Udine, Italy)—polyethylene Delta Cup—UHMWPE X (Lima-Lto, Udine, Italy); this took place six weeks later.

ResultAt 5-years follow-up the patient had no pain in his hip and was able to walk unaided, with a slight limp. He continued to have bilateral sensorineural hearing loss and impaired vision due to an ischaemic focus in the temporal sector of the posterior pole of his left eye.

DiscussionIt is obvious that elevated levels of heavy metals in blood and urine can cause major health problems in the population. The risk of cobalt toxicity in total hip arthroplasty has been well-known since the nineties; at 6.2%.7 The origin of this metallosis in our speciality is diverse. The effect of metal-on-metal bearings on increased metal ions in the blood is known, but there are other risks, such as the incorrect choice of bearings in revision surgery of hip prosthesis, after ceramic head fracture.4

The use of ceramic-on-ceramic bearings is widespread, and therefore the literature coincides in that it continues to be the gold standard in young patients where we seek high prosthetic survival influenced by the life expectancy and mechanical requirements of this group of patients. Ceramic-on-ceramic bearings have excellent tribological properties, which include resistance to corrosion and biocompatibility. The use of larger-diameter heads also increases range of motion and reduces the risks of luxation. However, ceramic has less elasticity and plasticity, which makes it susceptible to sudden failure. The frequency of third generation ceramic component fracture is less than 1%.5

Fragments resulting from ceramic component fracture are microscopic and can cause irreparable damage to a new prosthesis.6 In 2003 Matziolis et al.7 reported that ceramic debris after fracture can have an abrasive action on metal (chromium–cobalt alloy) causing particles to release into the blood stream. Histological study revealed fibrous tissue with pronounced and generalised metallosis. Therefore, we must choose the appropriate bearing for revision surgery after ceramic component fracture, avoiding soft (polyethylene-metal) bearings. The use of polyethylene–metal bearings after ceramic head fracture should be contraindicated.7,8 Various authors make the case for replacing the acetabular insert during revision surgery, even if it appears macroscopically normal, because microscopic ceramic material might be incrusted in it4,6,7 (Fig. 2C). By doing so, we can reduce the risk of excessive abrasion of the new components. In cases where there is damage at acetabular level and of the morse cone, it is recommended that all the components should be removed.8

The process of abrasion and depositing cobalt particles in the tissues causes soluble metal ions which pass into the blood stream and can cause symptoms of cobalt intoxication.9 Cobalt intoxication symptoms are constant and repeated, and target the respiratory tract (asthma, obstructive syndrome, pneumoconiosis, interstitial disease), skin (eczema, urticaria, photosensitivity to cobalt, cross-sensitisation) peripheral nervous system (sensory-predominant polyneuropathy), auditory nerve (hearing loss), optic nerve (visual field disturbances), cardiovascular system (myocardiopathy, cardiotoxicity), bone marrow (polycythaemia), thyroid gland (hypothyroidism), pancreas (type 2 diabetes mellitus) and teratogenicity. Cobalt intoxication causes multiple organ failure and in serious cases can result in death.9

X-ray and CAT are of great help in diagnosing metallosis. The images present a similar appearance to that of heterotopic ossication.9 This can be corroborated at intra-operative level; large infiltration of the tissues by metal particles is observed as black pigments (Fig. 2A, B) and occasionally clusters of metal particles that can be seen in imaging procedures (Fig. 2E).

Treatment in the event of ceramic component fracture is based on revision of the prosthesis and removal of the bearing components and change for a new ceramic-on-ceramic bearing.8 In cases where there is excessive damage of the morse cone it is recommended that the neck should be changed if it is modular, or the entire femoral component if it is monoblock.8 In cases where patients present metal intoxication symptoms the current literature offers no clear lines of treatment10; some studies have shown a dramatic reduction in blood metal ion levels after removal of the implant.11 In our case we decided to remove the implant given the symptoms of heavy metal poisoning and damage to the morse cone. Some authors propose the use of EDTA as a chelating agent in the treatment of cobalt toxicity, especially in cases with a positive clinical picture and poor condition. They consider that without this treatment the particles will not disappear from the lymphatic system.11,12 As a result of removing the prostheses we achieved a gradual reduction of cobalt levels and resolution of systemic symptoms.

ConclusionsWe must be vigilant when symptoms occur that are apparently alien to our speciality, all the more so in such extensive procedures as hip or knee prostheses.

The correct choice of bearings is essential in hip arthroplasty, especially in revision cases. We must pay special attention to possible complications in these cases.

Studies are necessary that offer directives for the management of cases of heavy metal poisoning in patients with THP.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of humans and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their centre of work regarding the publication of patient data

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have received no financial help whatsoever to undertake this study, nor have they signed agreements for which they will receive benefits or fees from any commercial entity. Moreover, no commercial entity has paid or will pay foundations, educational institutions or other not-for-profit organisations to which the authors are affiliated.

Please cite this article as: Pelayo-de Tomás JM, Novoa-Parra C, Gómez-Barbero P. Toxicidad por cobalto después de la revisión a una artroplastia total de cadera posterior a fractura de cabeza cerámica. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:203–207.