To determine whether surgical treatment delayed for more than 48h in patients with cauda equina syndrome (CES) influenced the clinical outcome.

Material and methodsA retrospective study of 18 patients treated in our hospital from March 2000 to January 2012, after presenting with CES. The pre- and post-operative clinical status was determined: existence of back pain and/or sciatica, sensory disturbance in the perineum, sensory and motor deficits in the lower extremities, and the degree of sphincter incontinence (complete or incomplete CES). A clinical assessment was performed using the Oswestry disability index.

ResultsAs regards the onset of symptoms, 44% (8 of 18) of patients were treated at an early stage (within 48h). None of the patients with complete CES operated in the early stage had urinary incontinence, and also had greater motor recovery. Of the 5 patients with complete CES who underwent delayed surgery, 3 showed residual urinary incontinence. A mean of 12.55 was obtained on the Oswestry disability index scale at the end of follow-up.

ConclusionAlthough no statistically significant difference was found in our study, we observed greater motor and sphincter recovery in patients who were operated on within 48h.

Constatar si la demora en más de 48h en el tratamiento quirúrgico de los pacientes con síndrome de cauda equina (SCE) influyó en el resultado clínico de nuestros pacientes.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de 18 pacientes intervenidos en nuestro centro desde marzo de 2000 a enero de 2012, tras presentar SCE. Se recogió la situación clínica pre- y postoperatoria: existencia de dolor lumbar y/o ciático, alteración sensitiva en periné, déficit motor y sensitivo en extremidades inferiores y el grado de incontinencia esfinteriana (SCE completo o incompleto). Se realizó una valoración mediante el índice de discapacidad de Oswestry.

ResultadosTeniendo en cuenta el inicio de los síntomas, el 44% (8 de 18) de los pacientes se intervinieron de forma precoz (menos de 48h). Ninguno de los pacientes con SCE completo intervenidos precozmente tuvieron incontinencia urinaria residual, presentando además mayor grado de recuperación motora. De los 5 pacientes con SCE completo intervenidos de forma tardía (más de 48h), 3 continuaron con incontinencia urinaria residual. Al final del seguimiento se obtuvo una media de 12,55 en las escala de discapacidad de Oswestry.

ConclusiónAunque no se han encontrado diferencias estadísticamente significativas, en nuestra serie hemos observado mayor recuperación motora y esfinteriana en los pacientes que fueron intervenidos antes de las 48h.

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a severe and rare neurological condition, consisting of conus medularis distal nerve root compression.1 In the majority of cases the cause is a lumbar disc hernia that leads to root injury due to mechanical pressure, ischaemia and venous congestion. Diagnosis is clinical and involves bladder and/or rectal sphincter dysfunction. It may also be associated with different degrees of motor and sensory deficit in the lower limbs. Depending on the degree of severity, it is possible to distinguish between incomplete CES (altered sensitivity, a reduction in the jet of urine although control of the beginning and end of urination is kept) and complete CES, in which urine is retained with incontinence due to overspill.2 If the condition progresses it may lead to permanent incontinence, sexual impotence and paraplegia.1 1% or 2% of the population will suffer a symptomatic lumbar disc hernia at some point in their life, and only 2%–6% of the hernias that require surgical treatment are due to the development of a horse tail syndrome.3–5 Although it is controversial, the chief prognostic factor for neurological recovery seems to be urgent decompression,6 although the time limit for this has not been clearly established. Some authors have therefore described a significant improvement in patients operated before 48h.1 On the other hand, a more recent study found no differences between patients operated before 48h and those operated after this time.7

The chief aim of our study is to find whether a delay of more than 48h in surgical treatment influences the clinical outcome for our patients, and to determine whether sphincter recovery is better in those patients with a complete established syndrome when surgical decompression occurs in under 48h.

Material and methodsA retrospective study was carried out of 18 patients (8 men and 10 women) operated in our hospital from March 2000 to January 2012 after presenting CES due to lumbar disc hernia. The inclusion criteria set were: patients who presented complete or incomplete sphincter dysfunction that could be associated with paresthesia or saddle anaesthesia, as well as lumbar or sciatic pain. In all cases the presence of massive disc hernia was detected using NMR or CAT. All of the patients with CES due to other causes were excluded (fracture or haematoma). We classify the reason for a delay in surgery into 4 groups: diagnostic (the patient did not visit primary health care or was not referred to the hospital), imaging tests (a delay in obtaining these), the patient (initial rejection of the proposed surgical treatment) and the surgeon (the non-availability of the surgeon in the spinal column unit). Urine retention diagnosis was clinical (a bladder that required catheterisation). The patients were not studied using ultrasound. The symptoms were considered to start at the moment when the genitourinary symptoms appeared, apart from lumbar or sciatic pain.

Data corresponding to the pre- and postoperative clinical situation: lumbar and/or sciatic pain, sensory alteration in the perineum, motor and sensory deficit in the lower limbs and the degree of sphincter incontinence (complete or incomplete CES). The ASIA muscle groups were evaluated for the lower limbs (L2: iliac psoas, L3: quadriceps, L4: anterior tibial, L5: long big toe extensor and S1: sural triceps).8 The Medical Research Council classification was used to quantify muscle strength (0: absence of contraction) to (5: normal contraction) in each of the above-mentioned muscle groups. Thus in each leg the maximum score is 25 points in the absence of paresis, while 50 points is the maximum overall score for both legs (25 for each one).8

The surgical procedure consisted of unilateral laminectomy and discectomy using a conventional approach, associated with posterolateral arthrodesis in only one case. In all cases an attempt was made to determine the influence of the delay in surgery (more than 48h) for each isolated symptom, so that we consider surgery prior to this time limit to be an early operation.

The minimum period of follow-up for analysis of the results was 6 months following the surgical operation. To evaluate the results complete physical examination took place together with evaluation using Oswestry's disability index.9 Returning to work was also recorded, using the Kirkaldy-Willis classification for functional results: excellent (the patient returned to their job), good (they returned to work, but with limitations for other activities and sometimes need to rest for several days), mediocre (the type of work or the duration of the working day was changed) or poor (they did not return to work).10 We recorded intra- and postoperative complications, as well as the number of repeat procedures.

Statistical analysisAn exploratory data analysis was performed: average and standard deviations for continuous data; frequencies and percentages for qualitative data. To evaluate the clinical and socio-demographic differences between both groups (operated within or after 48h). Fisher's exact test (categorical variables) was used together with Wilcoxon's non-parametric test for independent samples (continuous variables). In the same way the association between socio-demographic and clinical variables and the degree of paresis before and after the operation way evaluated. Wilcoxon's non-parametric test for independent samples was used for this purpose. The difference in the degree of paresis between both measurements was defined (paresis after the procedure and paresis prior to the same). To establish associations between the factors studied with the said variable Wilcoxon's non-parametric test for independent samples was used. The state of sphincters was evaluated using McNemar's test. This was applied to the patient sub-samples with a delay of less than 48h and more than 48h.

Finally the association of motor functions was analysed before and after the procedure, together with the difference between both measurements, as well as sphincter recovery (urinary and intestinal, before and after the procedure) with delay in surgery and the cauda equina state. A combined variable was created for this with surgical delay (of up to 48h vs more than 48h) and degree of severity (complete/incomplete). The Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test for quantitative variables was used for this, while Fisher's exact test was used for qualitative factors.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SAS 9.3 system, and P was considered to be significant when P<0.05.

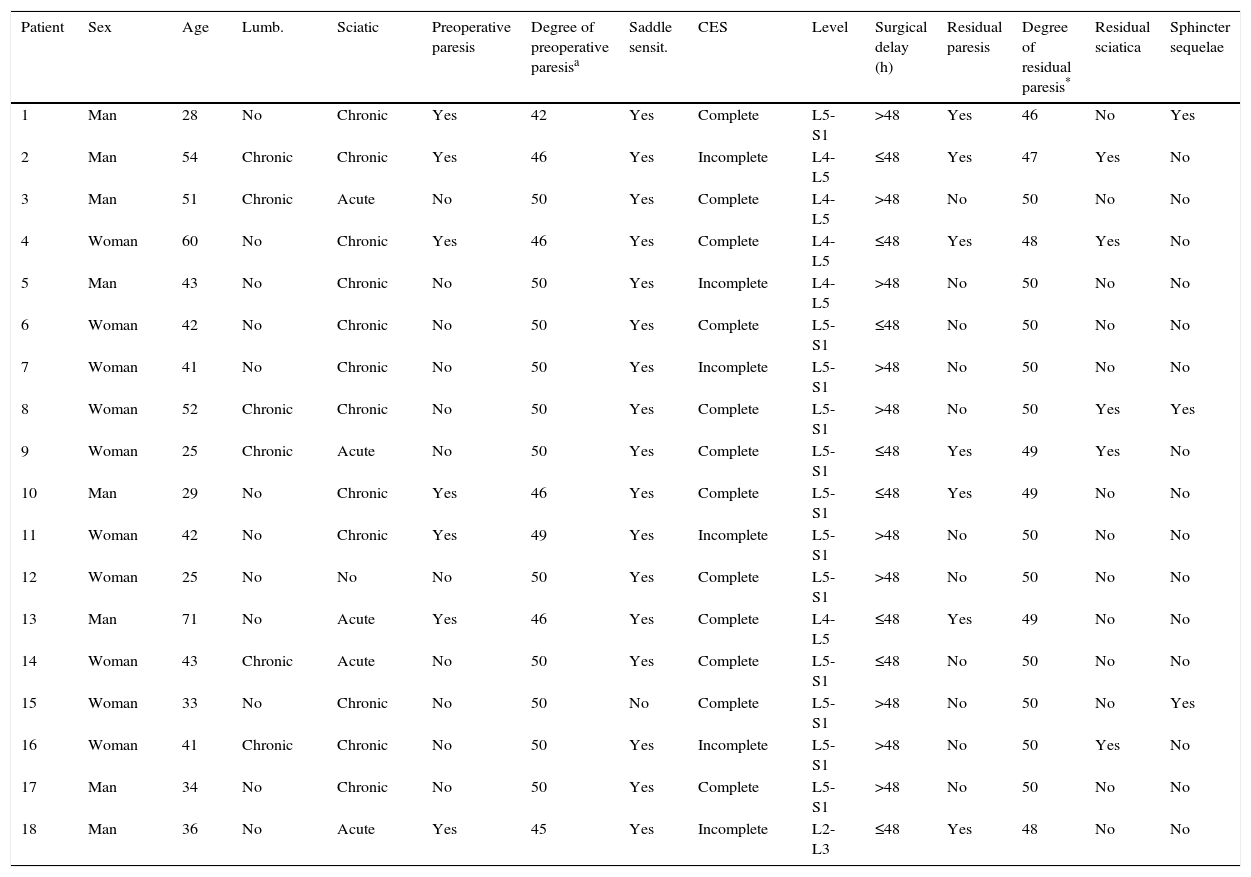

ResultsThe average age of the patients was 41.7 years old (range 25–71) with an average follow-up of 12 months (range 6–24). The descriptive data of the series are shown in Table 1. The most frequently affected level was L5-S1 (66.7%). Of the 18 cases, 12 patients presented a complete CES (only urinary in 6 cases, intestinal and urinary in 5 cases and only intestinal in one case) while the other 6 were incomplete CES. As a whole, the patients who were operated corresponded to 5.8% (18 of 310) of the lumbar discectomies operated in our hospital during this period of time. Taking into account the start of genitourinary symptoms, 44% (8 of 18) of our patients were operated before 48hrs. In the patients operated after 48h from the start of symptoms (10 patients), the reasons for the delay were delay in diagnosis in 6 cases (the patient did not visit or was not referred to the emergency department), delay in obtaining complementary tests in 3 cases, and rejection of the treatment by one patient. 6 patients presented chronic lumbar pain before the operation (developing over more than 3 months in all cases). This figure doubled when this symptom was analysed after the surgical operation. There was no statistically significant difference depending on the delay in surgery. All of the patients except one has sciatic pain (7 bilaterally), and it persisted in 5 patients after the operation. Delay in surgery did not influence this finding, either.

Description of the series studied.

| Patient | Sex | Age | Lumb. | Sciatic | Preoperative paresis | Degree of preoperative paresisa | Saddle sensit. | CES | Level | Surgical delay (h) | Residual paresis | Degree of residual paresis* | Residual sciatica | Sphincter sequelae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Man | 28 | No | Chronic | Yes | 42 | Yes | Complete | L5-S1 | >48 | Yes | 46 | No | Yes |

| 2 | Man | 54 | Chronic | Chronic | Yes | 46 | Yes | Incomplete | L4-L5 | ≤48 | Yes | 47 | Yes | No |

| 3 | Man | 51 | Chronic | Acute | No | 50 | Yes | Complete | L4-L5 | >48 | No | 50 | No | No |

| 4 | Woman | 60 | No | Chronic | Yes | 46 | Yes | Complete | L4-L5 | ≤48 | Yes | 48 | Yes | No |

| 5 | Man | 43 | No | Chronic | No | 50 | Yes | Incomplete | L4-L5 | >48 | No | 50 | No | No |

| 6 | Woman | 42 | No | Chronic | No | 50 | Yes | Complete | L5-S1 | ≤48 | No | 50 | No | No |

| 7 | Woman | 41 | No | Chronic | No | 50 | Yes | Incomplete | L5-S1 | >48 | No | 50 | No | No |

| 8 | Woman | 52 | Chronic | Chronic | No | 50 | Yes | Complete | L5-S1 | >48 | No | 50 | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Woman | 25 | Chronic | Acute | No | 50 | Yes | Complete | L5-S1 | ≤48 | Yes | 49 | Yes | No |

| 10 | Man | 29 | No | Chronic | Yes | 46 | Yes | Complete | L5-S1 | ≤48 | Yes | 49 | No | No |

| 11 | Woman | 42 | No | Chronic | Yes | 49 | Yes | Incomplete | L5-S1 | >48 | No | 50 | No | No |

| 12 | Woman | 25 | No | No | No | 50 | Yes | Complete | L5-S1 | >48 | No | 50 | No | No |

| 13 | Man | 71 | No | Acute | Yes | 46 | Yes | Complete | L4-L5 | ≤48 | Yes | 49 | No | No |

| 14 | Woman | 43 | Chronic | Acute | No | 50 | Yes | Complete | L5-S1 | ≤48 | No | 50 | No | No |

| 15 | Woman | 33 | No | Chronic | No | 50 | No | Complete | L5-S1 | >48 | No | 50 | No | Yes |

| 16 | Woman | 41 | Chronic | Chronic | No | 50 | Yes | Incomplete | L5-S1 | >48 | No | 50 | Yes | No |

| 17 | Man | 34 | No | Chronic | No | 50 | Yes | Complete | L5-S1 | >48 | No | 50 | No | No |

| 18 | Man | 36 | No | Acute | Yes | 45 | Yes | Incomplete | L2-L3 | ≤48 | Yes | 48 | No | No |

Sciatica: preoperative sciatica; Lumb: preoperative lumbalgia; CES: equina caudal syndrome; Saddle: saddle anaesthesia and/or hypoesthesia.

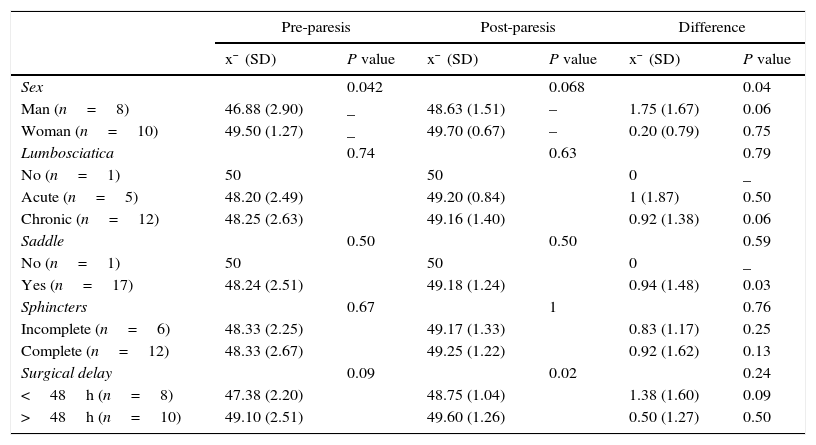

We found that the patients operated after a delay of longer than 48h commenced with less motor involvement (average 49±2.5), in comparison with those operated before 48h (average 47.4±2.2). At the end of the follow-up, in the group operated early the motor score was 48.7±1, while in the group operated later it was 49.6±1.2. We therefore observed a higher degree of motor recovery in the group operated before 48h (average 1.37±1.59), than in the group operated later (average 0.50±1.27) (P=0.24). Nevertheless, this difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Motor recovery in relation to the factors studied.

| Pre-paresis | Post-paresis | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x¯ (SD) | P value | x¯ (SD) | P value | x¯ (SD) | P value | |

| Sex | 0.042 | 0.068 | 0.04 | |||

| Man (n=8) | 46.88 (2.90) | _ | 48.63 (1.51) | – | 1.75 (1.67) | 0.06 |

| Woman (n=10) | 49.50 (1.27) | _ | 49.70 (0.67) | – | 0.20 (0.79) | 0.75 |

| Lumbosciatica | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.79 | |||

| No (n=1) | 50 | 50 | 0 | _ | ||

| Acute (n=5) | 48.20 (2.49) | 49.20 (0.84) | 1 (1.87) | 0.50 | ||

| Chronic (n=12) | 48.25 (2.63) | 49.16 (1.40) | 0.92 (1.38) | 0.06 | ||

| Saddle | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.59 | |||

| No (n=1) | 50 | 50 | 0 | _ | ||

| Yes (n=17) | 48.24 (2.51) | 49.18 (1.24) | 0.94 (1.48) | 0.03 | ||

| Sphincters | 0.67 | 1 | 0.76 | |||

| Incomplete (n=6) | 48.33 (2.25) | 49.17 (1.33) | 0.83 (1.17) | 0.25 | ||

| Complete (n=12) | 48.33 (2.67) | 49.25 (1.22) | 0.92 (1.62) | 0.13 | ||

| Surgical delay | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.24 | |||

| <48h (n=8) | 47.38 (2.20) | 48.75 (1.04) | 1.38 (1.60) | 0.09 | ||

| >48h (n=10) | 49.10 (2.51) | 49.60 (1.26) | 0.50 (1.27) | 0.50 | ||

SD: standard deviation; x¯: arithmetic mean.

Respecting sphincter deficit, at admission 12 patients had urinary and/or intestinal incontinence or retention (complete syndrome), while the others had an incomplete syndrome. Although no statistically significant differences were attained (P=0.18), all of the patients operated early presented sphincter recovery. In 3 of the 5 patients operated later their urinary incontinence persisted. The intestinal symptoms present in 6 cases were resolved in all of them.

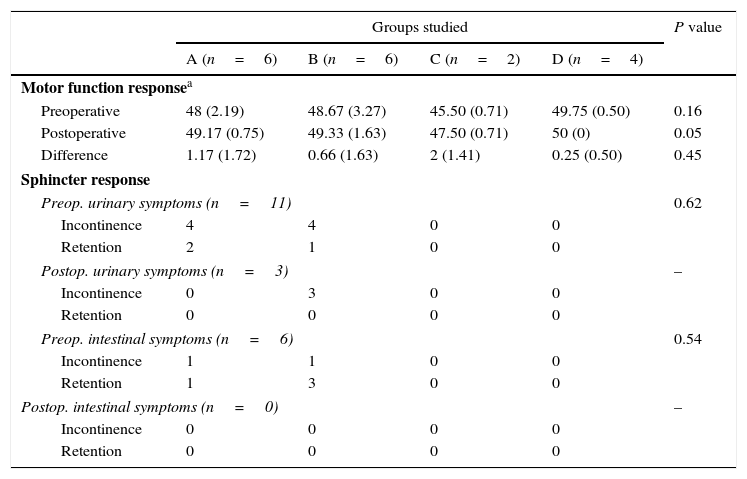

Analysis according to subgroups, taking into account the time surgery was delayed and the presence of complete or incomplete CES at the start of symptoms, all 4 groups studied presented an improvement in terms of motor function response. Nevertheless, there were no statistically significant differences between the said groups. Respecting sphincter response, no patient had intestinal symptoms (incontinence, retention) after the operation. The patients with incomplete CES had no residual urinary or intestinal symptoms. On the other hand, in patients with complete CES surgical delay was not associated with sphincter response before the operation (P value: 0.62 urinary symptoms; P value: 0.54 for intestinal symptoms) (Table 3).

Analysis in subgroups for motor and sphincter function recovery taking surgical delay time into account and the presence of complete or incomplete CES at the start of symptoms.

| Groups studied | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (n=6) | B (n=6) | C (n=2) | D (n=4) | ||

| Motor function responsea | |||||

| Preoperative | 48 (2.19) | 48.67 (3.27) | 45.50 (0.71) | 49.75 (0.50) | 0.16 |

| Postoperative | 49.17 (0.75) | 49.33 (1.63) | 47.50 (0.71) | 50 (0) | 0.05 |

| Difference | 1.17 (1.72) | 0.66 (1.63) | 2 (1.41) | 0.25 (0.50) | 0.45 |

| Sphincter response | |||||

| Preop. urinary symptoms (n=11) | 0.62 | ||||

| Incontinence | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| Retention | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Postop. urinary symptoms (n=3) | – | ||||

| Incontinence | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Retention | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Preop. intestinal symptoms (n=6) | 0.54 | ||||

| Incontinence | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Retention | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Postop. intestinal symptoms (n=0) | – | ||||

| Incontinence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Retention | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

CES: equine caudal syndrome.

A: surgical delay≤48h and complete CES; B: surgical delay>48h and complete CES; C: surgical delay≤48h and incomplete CES; D: surgical delay>48h and incomplete CES.

Using the Kirkaldy-Willis method, the functional results were that results in 11 patients were excellent or good, in 5 they were poor and 2 did not respond. On the other hand, at the end of follow-up an average score of 12.55 (minimum disability) was obtained on Oswestry's disability scale.

Intraoperative complications consisted of 2 dural tears. One of these was resolved using suture during the operation. The other was diagnosed after the operation and caused a pseudomeningocele that was treated conservatively. The postoperative complications include a superficial infection. At the end of follow-up we recorded 2 cases of hernia relapse, one of which had to be operated again with a new discectomy and instrumented posterolateral arthrodesis.

DiscussionAlthough there is unanimous agreement on the need for surgery in case of cauda equina syndrome, we find diverse and contradictory results in the literature regarding the time window during which surgical decompression should take place.1,4 The majority of authors accept that the main modifiable prognostic factor is urgent surgical decompression, for which some studies have set a limit of 24–48h.1,4,11 Nevertheless, to be able to define the delay until surgery it is important for there to be agreement on when the syndrome commenced, and this point is controversial. The percentage of patients who receive early surgical treatment (before 48h) varies substantially between different authors, with figures that run from 45% to 88%.7,12,13 Taking the start of genitourinary symptoms into account, only 44% of our patients were operated before 48h. We have therefore emphasised the importance of education about the severity of this ailment for our patients and general practitioners, while magnetic resonance equipment is now available over longer times.

Some authors2,6,14 believe the prognosis basically depends on the intensity of the injury, as complete or incomplete. Sun et al. recently described the pattern of progression in the majority of cases: from an early incomplete injury to a complete one.15 If patients are operated early this will prevent some incomplete injuries from progressing to complete ones. The prognosis for the syndrome is more favourable when it is still incomplete at the moment of surgical decompression.

McCarthy et al. analysed which factors influence the functional and sphincter function results over the long term in patients with cauda equina syndrome.7 In their series of 46 cases that were operated they found that the duration of symptoms prior to surgery and the speed of development of the syndrome bore no relation to the postoperative evolution of their patients. Nor were their authors2,5,16 able to show any differences. However, this contrasts with the observations of the majority of authors in different series. In a retrospective study Shapiro13 found 100% recovery in urinary symptoms in 14 patients whose delay until surgery had been less than 48h, while in those whose surgical delay exceeded 48h the corresponding recovery was 33%. This was reflected in other studies, showing that patients operated early had a better probability of recovering bladder function.1,17 Although the differences were not statistically significant, in our series all of the patients operated early recovered bladder functioning. Urinary incontinence persisted in 3 of the 5 patients operated late. The intestinal symptoms which had been present in 6 cases were all resolved.

Regarding the degree of motor recovery, a meta-analysis published in the year 2000 showed significantly better sensory-motor results in patients operated before 48h.1 Likewise, Kholes et al. concluded that the sooner surgery takes place, even in the first 24h, the better the results.18 In our series we found an improvement in the degree of motor recovery in the group of patients treated early. Although motor recovery was greater in the group operated early, it did not equal the scores of the other group. A recent paper analyses the cases of 5 patients with CES subjected to discectomy with early decompression; in spite of not being able to prove the benefits of early decompression, it concludes that this will never be negative for the prognosis and may prevent progression to complete sphincter paralysis.19

The resulting score on Oswestry's disability index in our series was 12.55 (minimum disability). This is better than the result published for the series of McCarthy et al.,7 which was 29.2. There were more complications in our series (2 dural tears and one superficial infection) than in some other works,16 although there were fewer than in another similar study (13 complications in 42 patients).7 Although some authors achieve good results with limited exposures,15 we believe that we should insist on a suitable exposure using broad laminectomies or bilateral ones if necessary, to prevent any possible dural tear.

Litigation often occurs when the symptoms of deficit persist in a patient, especially when the probable results have not been completely explained or understood by the patient. Nevertheless, the only situation that may be considered a medical error is when a true established cauda equina syndrome is not diagnosed and is therefore not treated properly. Some authors20 observed that a surgical delay of more than 48h is associated with verdicts in favour of the patient, at 83% probability. In our series one patient filed a lawsuit due to the presence of deficit symptoms, not because of a delay in surgery.

Given the retrospective nature of this study its limitations are that treatment was not assigned at random respecting time of evolution. The size of the sample in our series is small, given the rarity of this entity. This may have contributed to not finding a statistically significant association between the variables studied.

ConclusionsIn our study we found a tendency to better motor and sphincter function recovery in patients operated before 48h, although these results are not statistically significant. Revision of the bibliography showed benefits in those patients operated before 48h, with better results in their sensory-motor deficit and sphincter functioning.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that for this research no experiments were performed in human beings or animals.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the paper. This document is held by the corresponding author.

FinancingNo source of financing was used for this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Foruria X, Ruiz de Gopegui K, García-Sánchez I, Moreta J, Aguirre U, Martínez-de los Mozos JL. Síndrome de cauda equina por hernia discal lumbar: demora quirúrgica y su relación con el pronóstico. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:153–159.