To analyse the clinical, quality of life, and healthcare quality outcomes obtained in a series of patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA), who were empowered and monitored using the AVIP application. These results will be compared with a control group followed through a standard protocol.

Material and methodRandomised clinical trial with parallel groups involving patients with an indication for THA. Clinical variables were measured and compared using the WOMAC and mHHS, pain assessed by the VAS, quality of life with the SF-12 test. Walking capabilities were analysed using the Functional Gait Assessment Scale, along with satisfaction levels assessed through the SUCE questionnaire, and perceived anxiety levels related to the process.

ResultsA total of 68 patients were evaluated, with 31 patients in the AVIP group and 33 in the Control group completing the follow-up. Both groups demonstrated improvement in clinical outcomes based on the WOMAC and mHHS hip tests, a reduction in perceived pain, and an enhancement in quality of life according to the SF-12 test. Patients in the AVIP study group exhibited non-inferiority in clinical outcomes and satisfaction compared to the control group, as well as lower anxiety levels and improved walking capabilities after the first month of follow-up. Notably, 82.25% of the follow-up visits for this group were conducted remotely.

ConclusionThe implementation of a mHealth application like AVIP can be safely offered to selected patients undergoing hip arthroplasty, enabling effective monitoring and providing continuous information and training.

Analizar los resultados clínico-funcionales, de calidad de vida y de satisfacción obtenidos en una serie de pacientes tratados mediante artroplastia total de cadera (ATC), capacitados y seguidos mediante la aplicación AVIP. Comparar los resultados con un grupo control seguido mediante un protocolo habitual.

Material y métodoEnsayo clínico aleatorizado con grupos paralelos que incluyó a pacientes con indicación de ATC. Se analizaron variables clínicas mediante los test WOMAC y mHHS, el dolor en EVA y la calidad de vida con el test SF-12. Se registraron las capacidades para la marcha mediante la escala de evaluación funcional de la marcha, el nivel de satisfacción con el seguimiento mediante el cuestionario SUCE y el nivel de ansiedad percibido.

ResultadosSe evaluó a un total de 68 pacientes, completando el seguimiento 31 pacientes incluidos en el grupo AVIP y 33 en el grupo control. Ambos grupos mostraron mejoría en los resultados clínicos según los test WOMAC y mHHS, reducción del dolor y mejor calidad de vida según el test SF-12. Los pacientes incluidos en el grupo a estudio AVIP mostraron una no inferioridad de resultados clínicos y de satisfacción respecto al grupo control, así como menor ansiedad y mejores capacidades para la marcha tras el primer mes de seguimiento, realizándose el 82,25% de las visitas de seguimiento correspondientes a este grupo de manera telemática.

ConclusiónLa implementación de una aplicación mHealth como AVIP puede ser ofrecida de manera segura a pacientes seleccionados tratados mediante ATC, permitiendo realizar un seguimiento efectivo y proporcionando una información y capacitación continuada.

Osteoarthritis is one of the most common joint diseases worldwide. It progresses causing pain and functional disability and results in an increasing number of prosthetic surgical interventions mainly to the hip and knee joints.1–3 The main goal of joint replacement procedures is to restore the best possible physical function and reduce pain and factors that are considered to have a major impact on independence and social participation, and therefore on quality of life.3,4 In fact, total hip arthroplasty (THA) has been described as ‘the operation of the century’.5 Despite this, the procedure can be physically and psychologically challenging for patients.6,7 Current practices both in the preoperative phase, as well as during the admission and immediate postoperative process, and during outpatient follow-up have evolved with the ultimate aim of reducing the number of consultations and shortening hospital admission and recovery times. However, this in turn has been associated with a significant reduction in the amount of time caring for the patient and, therefore, in their knowledge of the entire process of the prosthetic intervention, resulting in a period of increased physical and psychological stress. Admission on the day of surgery and a shortened hospital stay sometimes make it difficult to coordinate the initial guidelines with the rehabilitation team and to obtain adequate knowledge about the management of the prosthetic implant.8 In this context, it is very complex to establish a satisfactory relationship between the medical, rehabilitation and nursing team and the patient undergoing prosthetic surgery, with the result that many people continue to experience pain and functional problems after discharge from hospital.1,6

Preoperative education and preparation play a key role in helping patients cope with the postoperative period. Adequate pain perception and understanding by the patient, together with detailed information about the operation, are essential elements in reducing anxiety and promoting active recovery. After the operation, the long-term success of the arthroplasty depends largely on training in the use of the prosthesis in daily life.9,10

Recently, mobile applications have played an important role in monitoring and motivating patients to participate in their health management.11 These mobile health (mHealth) applications aim to improve patients’ participation in health-related processes and facilitate self-management of different aspects of their well-being. They focus on empowering patients to manage medical processes in the context of a comprehensive patient-centred model of healthcare.12

Although some applications exist for patients undergoing hip or knee replacement surgery, most are associated with specific surgeons and are not available in our national health system and, therefore, none of these applications have been evaluated for their effectiveness in improving quality of care, clinical outcomes, and quality of life for patients.

The aim of this study is to develop an innovative mobile application for THA patients. Then, to evaluate the clinical–functional outcomes, quality of life, and quality of care obtained in a series of patients who were tele-monitored using this application, and to compare them with a cohort of patients following our centre's usual THA follow-up protocol. As a secondary objective of our study, we will evaluate the level of satisfaction of both treatment groups, their anxiety about the surgical process, and the level of information received. Finally, we will analyse the potential reduction in the need for outpatient care of the patients included in the project, as well as their level of satisfaction with the use of the AVIP (Prosthetic Virtual Friend) application.

The AVIP application (Prosthetic Virtual Friend)13In collaboration with an expert in software development and with the financial support of the SECOT Foundation (Spanish Society of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology), an application was developed to address the needs of patients undergoing hip replacement surgery. This application, which can be accessed from any device with an Internet connection (mobile phone, tablet, or computer), provides evidence-based content on osteoarthritis of the hip and joint replacement procedures. Its main purpose is to provide patients with information and support, encourage adherence to treatment and promote self-care skills, and encourage active participation throughout the treatment process.

The content was developed by the Hip and Pelvis Unit at our centre, in collaboration with nurses specialising in the management of postoperative orthopaedic patients, rehabilitation specialists, and physiotherapists. The most frequently asked questions when treating patients after THA were identified, which helped to create relevant and useful content.

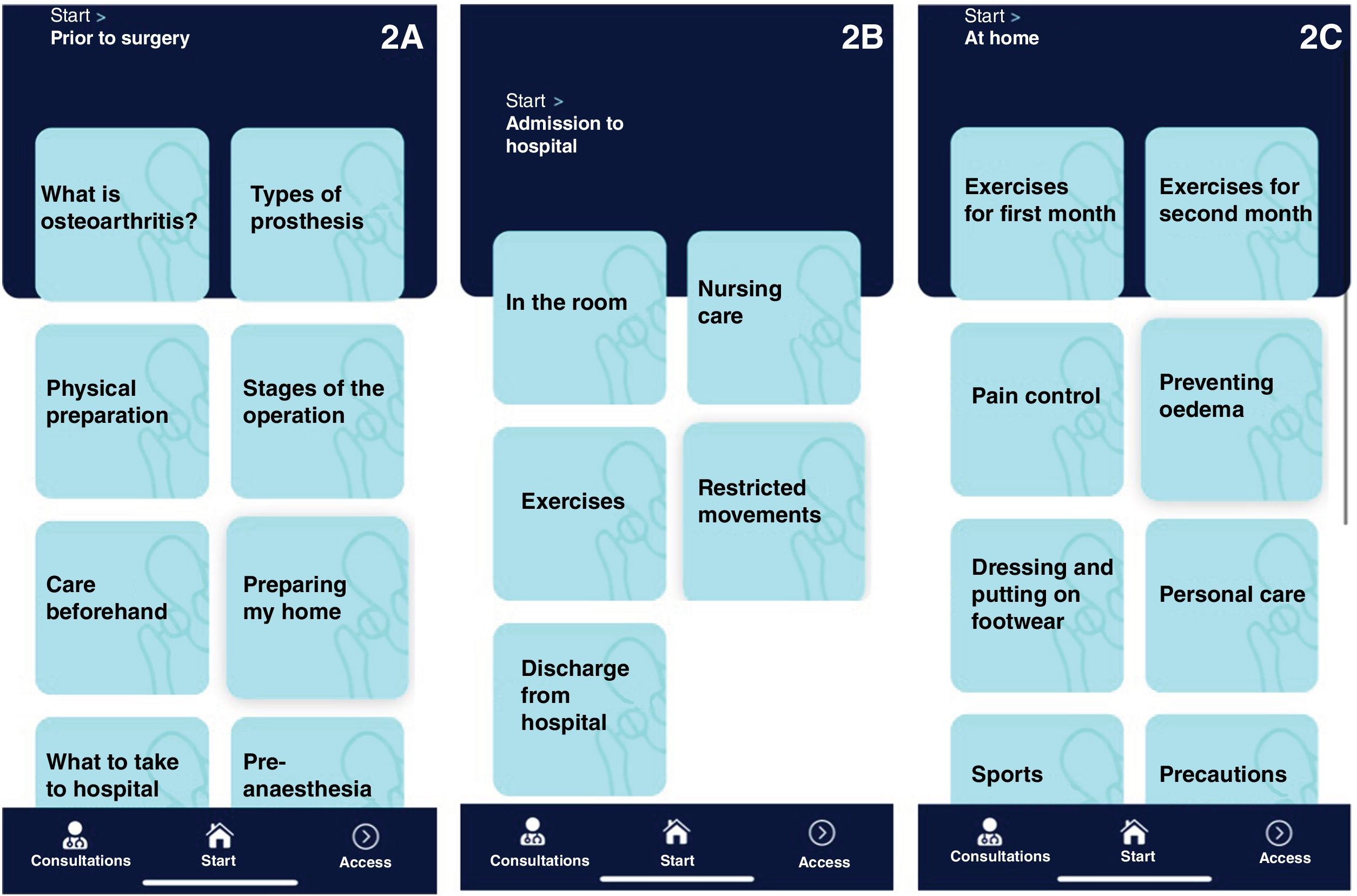

The application consists of 5 main sections (Fig. 1)

- –

Before my surgery: This section aims to reduce anxiety before the operation by providing useful information that increases knowledge about the healthcare process in which the patient is involved. It also provides essential information on how to prepare for surgery and hospital admission, as well as advice on exercise, the surgery timeline, and what to bring to hospital (Fig. 2A).

- –

Hospital admission: Useful information is provided for the immediate postoperative period to help patients adapt to an unfamiliar environment. It includes appropriate exercises for the first few days and precautions for the immediate management of the prosthesis (Fig. 2B).

- –

At home: This section provides tools for managing the prosthesis in the first few days and later in everyday life. Guided training is provided with exercises, precautions, and recommendations for daily, household, and sports activities. It also addresses frequently asked questions and provides information on potential adverse events in the early postoperative period (Fig. 2C).

- –

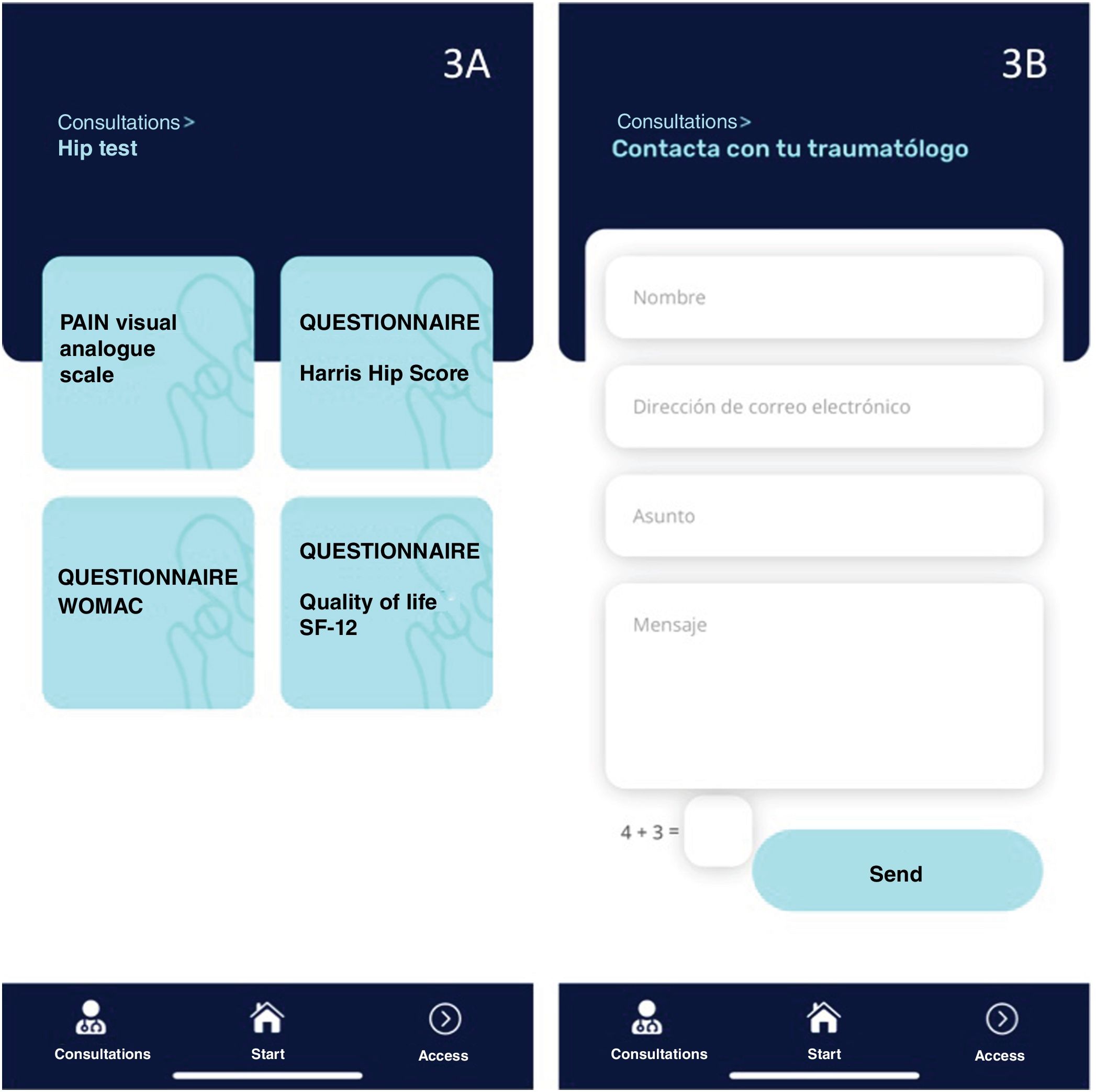

Consultations: In order to monitor patient progress, this section allows patients to self-complete the SF-12 quality of life questionnaire, the Modified Harris Hip Score (mHHS), and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) hip tests, and a visual analogue scale (VAS) to score pain (Fig. 3 A).

- –

Contact your orthopaedic surgeon: In this section, patients can easily contact the surgical team to address concerns or request consultation appointments. The main objective is to facilitate doctor-patient feedback (Fig. 3B).

A randomised, controlled, parallel group clinical trial was conducted. This study was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Research and Medicines Ethics Committee of our centre, reference number 134/2020. The results of this study are presented according to the CONSORT statement (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Clinical Trials).14

The sample size was calculated assuming a 1:1 ratio between groups, a power of 80%, and a significance level of 5%. Based on the work of Wasko et al.15 and Leiss et al.,16 we accepted a minimum clinically important difference (MCID) of 7.4 points and a standard deviation of 9.4 points for the mHHS. This resulted in an initial sample size of 26 in each treatment group. To address potential bias and increase the robustness of the study, we recruited 68 patients. All were selected between November 2021 and April 2022, and gave written consent to participate in the study (including the possibility of being assigned to one or the other research group), to undergo the operation, and have their data processed.

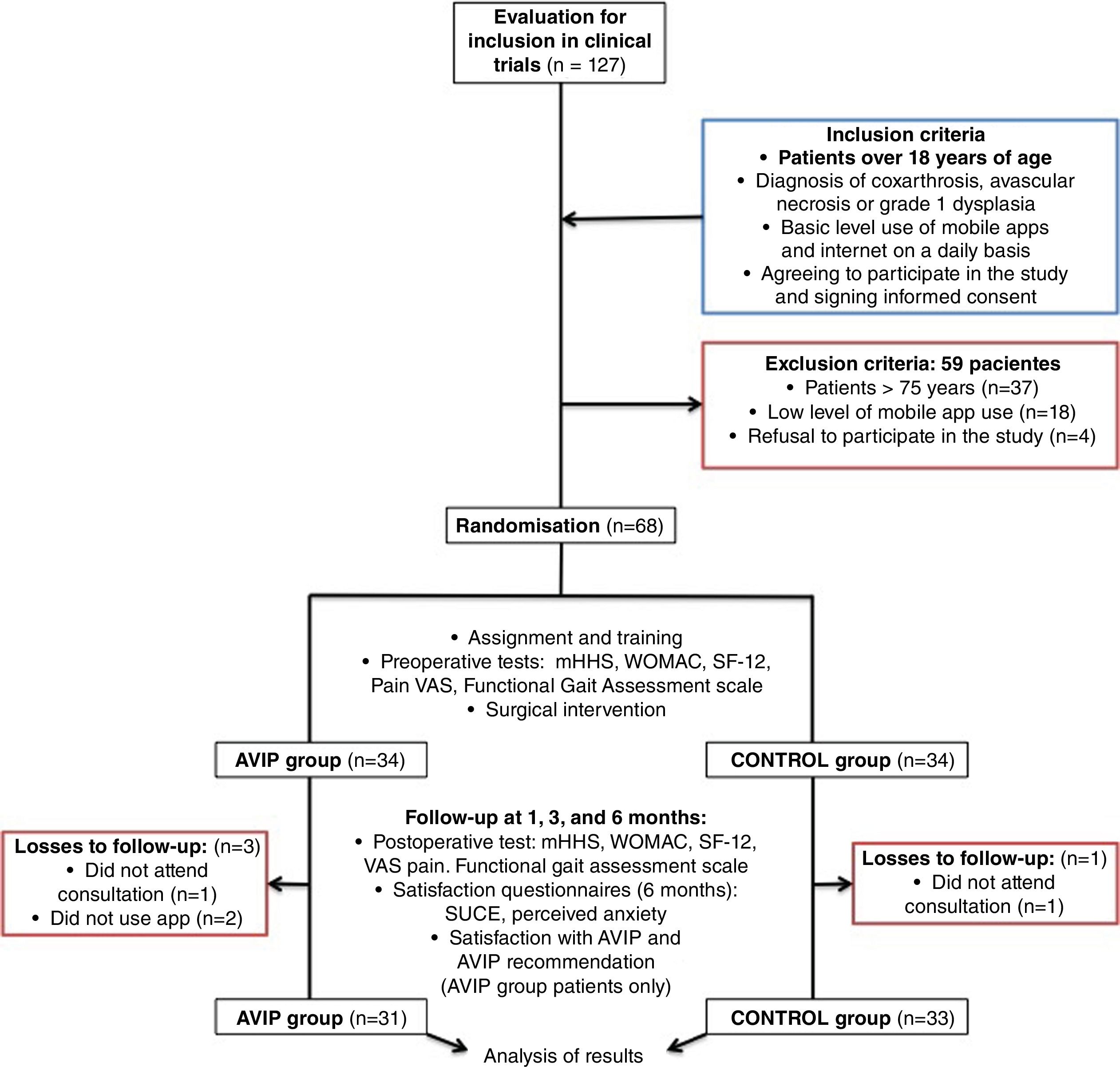

Inclusion criteria were patients over 18 years of age on the surgical waiting list for THA with a diagnosis of coxarthrosis, avascular necrosis, or Crowe's dysplasia type I, and with a basic level of daily use of the internet and mobile applications. This was decided after a telephone interview with the patients. Exclusion criteria were age over 75 years and insufficient level of mobile application use. From a surgical waiting list of 127 patients for THA surgery from May 2022 onwards, 68 patients were selected who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Microsoft Excel software was used to randomly select and assign 34 patients to the AVIP group and 34 to the control group. Once the study population was obtained and the randomisation phase was completed, the process of downloading the mobile application by the patients selected in the AVIP group began. In addition, 2 training sessions were held to teach these patients how to use the application and to encourage them to use it independently.

The mean age of the sample was 63.3 years (49–74 years SD 10.04); 36 patients (53%) were female and 32 were male (47%). The mean body mass index was 29kg/m2 (19–40kg/m2 SD 5.1). The aetiology for which primary hip arthroplasty was indicated was coxarthrosis in 51 cases (75%), avascular necrosis of the hip in 14 cases (20.6%), and mild hip dysplasia in 3 cases (4.4%).

All patients were operated on by the same surgical team between May 2022 and February 2023. Fifty-nine patients (87%) underwent implantation of an impacted wedge-shaped stem with hydroxyapatite coating in the metaphyseal area. In 9 patients (13%) a cemented double wedge polished stem was chosen. In all cases the acetabular component was a hemispherical cup with full hydroxyapatite coating. The choice of bearing torque was based on the specific characteristics of each patient.

After surgery and hospital discharge, patients in both treatment groups were assessed in outpatient clinics at 4 weeks. Patients in the AVIP group were then telemonitored at 3 and 6 months: they underwent a telephone assessment and completed the various questionnaires using the AVIP application. It is important to note that the non-face-to-face follow-up did not exclude follow-up radiographs performed at the primary care centre closest to the patient's home. The option of a face-to-face visit was offered if the patient so wished. They were also offered the opportunity to contact the surgical team to raise any concerns or request unscheduled consultations via the AVIP application in the ‘Contact the orthopaedic surgeon’ section. These contacts were logged and resolved by the researchers JDG, VED, and JFGF.

Patients in the control group continued to receive standard face-to-face follow-up visits at 3 and 6 months. At these visits, radiographs were taken in hospital and questionnaires were completed in the usual way.

The primary variable, used to calculate sample size to achieve adequate statistical power and significance was the self-report mHHS test. Secondary variables analysed included the SF-12 health-related quality of life test, the WOMAC hip function test, assessment of walking ability using the functional gait assessment scale,17 and measurement of patient-perceived pain using a VAS. All these variables were recorded at the preoperative visit, at 4 weeks after surgery, at 3 months, and at 6 months.

At the final control, other secondary variables were recorded and analysed, including patient satisfaction with outpatient consultations using the SUCE questionnaire18 and the level of anxiety experienced during the surgical process (on a visual analogue scale from 1 to 10 points). Patients in the AVIP group also expressed their level of satisfaction with the application (dissatisfied – satisfied – very satisfied) and whether they would recommend the AVIP application to other patients undergoing THA (yes/no). Fig. 4 shows the flowchart of the selection and follow-up method of the clinical trial.

SPSS 22 statistical software (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data processing. Descriptive analysis of categorical variables is expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. Both quantitative and qualitative variables were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Student's t-test was used for quantitative and qualitative variables and the χ2 test for qualitative variables. For all statistical analyses, the significance level was set at 5%.

ResultsInitially, 68 patients (34 in each treatment group) were enrolled in the study; 33 patients (97.1%) in the control group completed the 6 months of the study, as one patient did not attend his follow-up appointment at six months. In the AVIP group, 31 patients (91.2%) completed the study: 2 patients refused the telematic control and monitoring of results via the application from the first visit and one of them did not respond and did not attend consultation from the third month. The flowchart of the participants is shown in a Fig. 4.

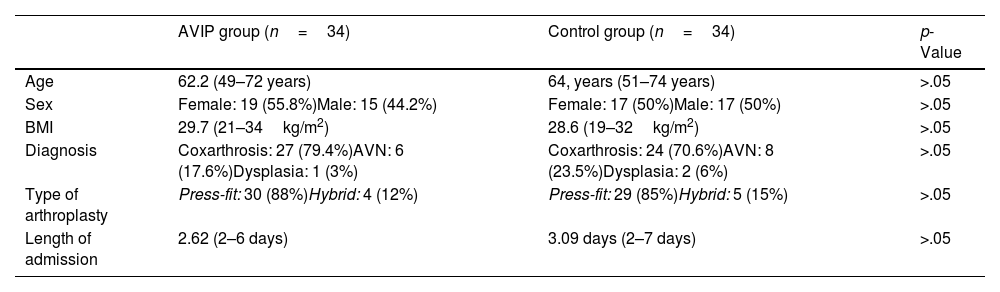

The demographic results are shown in Table 1, with no differences between the two treatment groups. The mean postoperative hospital stay was 2.62 days (2–6 days) in the AVIP group and 3.09 days (2–7 days) in the control group (p>.05).

Demographic data in both study groups.

| AVIP group (n=34) | Control group (n=34) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 62.2 (49–72 years) | 64, years (51–74 years) | >.05 |

| Sex | Female: 19 (55.8%)Male: 15 (44.2%) | Female: 17 (50%)Male: 17 (50%) | >.05 |

| BMI | 29.7 (21–34kg/m2) | 28.6 (19–32kg/m2) | >.05 |

| Diagnosis | Coxarthrosis: 27 (79.4%)AVN: 6 (17.6%)Dysplasia: 1 (3%) | Coxarthrosis: 24 (70.6%)AVN: 8 (23.5%)Dysplasia: 2 (6%) | >.05 |

| Type of arthroplasty | Press-fit: 30 (88%)Hybrid: 4 (12%) | Press-fit: 29 (85%)Hybrid: 5 (15%) | >.05 |

| Length of admission | 2.62 (2–6 days) | 3.09 days (2–7 days) | >.05 |

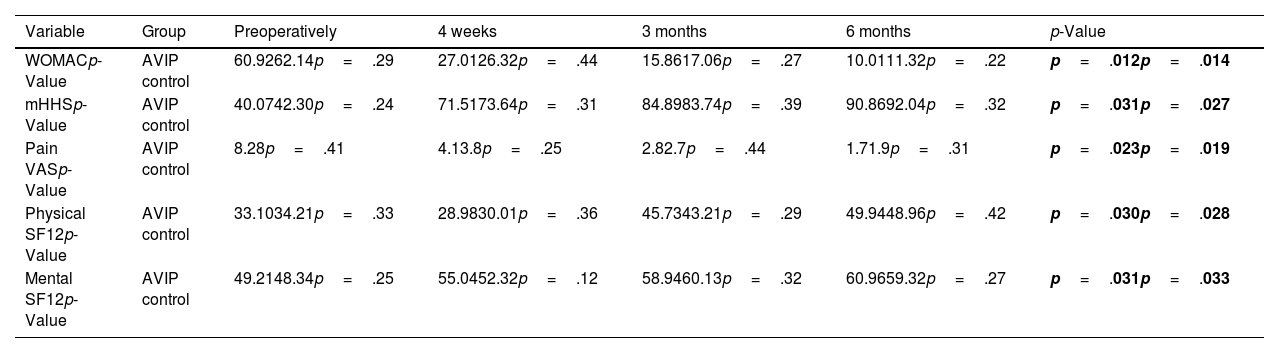

After analysing functional outcomes using the mHHS and WOMAC tests, we found a significant improvement in both treatment groups compared to their condition prior to the operation, with a gradual improvement in scores at all visits. There were no significant differences in these functional variables in favour of either treatment group at the end of follow-up (Table 2).

Functional, quality of life, and perceived pain results before surgery and during follow-up in both treatment groups studied.

| Variable | Group | Preoperatively | 4 weeks | 3 months | 6 months | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOMACp-Value | AVIP control | 60.9262.14p=.29 | 27.0126.32p=.44 | 15.8617.06p=.27 | 10.0111.32p=.22 | p=.012p=.014 |

| mHHSp-Value | AVIP control | 40.0742.30p=.24 | 71.5173.64p=.31 | 84.8983.74p=.39 | 90.8692.04p=.32 | p=.031p=.027 |

| Pain VASp-Value | AVIP control | 8.28p=.41 | 4.13.8p=.25 | 2.82.7p=.44 | 1.71.9p=.31 | p=.023p=.019 |

| Physical SF12p-Value | AVIP control | 33.1034.21p=.33 | 28.9830.01p=.36 | 45.7343.21p=.29 | 49.9448.96p=.42 | p=.030p=.028 |

| Mental SF12p-Value | AVIP control | 49.2148.34p=.25 | 55.0452.32p=.12 | 58.9460.13p=.32 | 60.9659.32p=.27 | p=.031p=.033 |

In bold, statistically significant results.

Similarly, both groups experienced a progressive improvement in their quality of life over the entire follow-up period, in both the physical and mental components as measured by the SF-12 quality of life questionnaire. There were also no significant differences when comparing the two groups (Table 2). A gradual decrease was recorded in pain perceived on a visual analogue scale by patients in both treatment groups compared with their previous condition, with no significant differences when comparing the groups (Table 2).

In terms of physical ability to walk, as measured by the functional gait assessment scale proposed by Holden et al.,17 in which each patient is given a score from 0 to 5 points according to his or her ability, both groups showed a progressive improvement at each successive appointment. At the 4-week visit, the AVIP group showed functional superiority in gait with a mean score of 3.9 points versus 3.2 points for the control group (p=.03). We found no significant differences in gait scores at 3 and 6 months (p>.05).

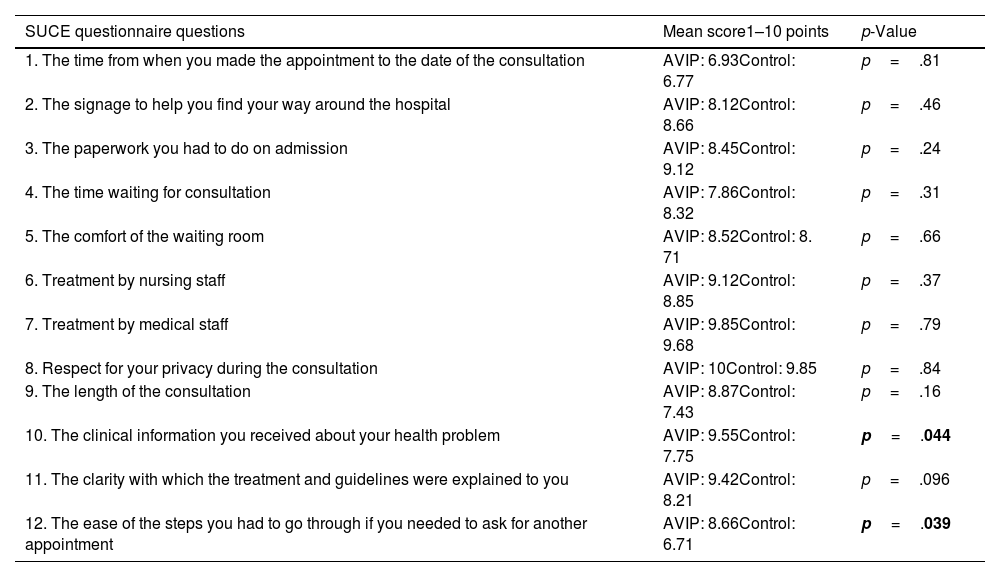

At the final control, all participants completed the SUCE questionnaire18 (Table 3). There was no evidence of superiority in either of the 2 cohorts studied, with a score of 8.58 points out of 10 in the AVIP group and 7.95 points in the control group (p>.05). When we analysed each question of the questionnaire individually, we recorded a better score in favour of the AVIP group in questions 10 (p=.044) and 12 (p=.039) (Table 3).

SUCE (outpatient user satisfaction questionnaire) and mean score obtained per question in each treatment group studied.

| SUCE questionnaire questions | Mean score1–10 points | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1. The time from when you made the appointment to the date of the consultation | AVIP: 6.93Control: 6.77 | p=.81 |

| 2. The signage to help you find your way around the hospital | AVIP: 8.12Control: 8.66 | p=.46 |

| 3. The paperwork you had to do on admission | AVIP: 8.45Control: 9.12 | p=.24 |

| 4. The time waiting for consultation | AVIP: 7.86Control: 8.32 | p=.31 |

| 5. The comfort of the waiting room | AVIP: 8.52Control: 8. 71 | p=.66 |

| 6. Treatment by nursing staff | AVIP: 9.12Control: 8.85 | p=.37 |

| 7. Treatment by medical staff | AVIP: 9.85Control: 9.68 | p=.79 |

| 8. Respect for your privacy during the consultation | AVIP: 10Control: 9.85 | p=.84 |

| 9. The length of the consultation | AVIP: 8.87Control: 7.43 | p=.16 |

| 10. The clinical information you received about your health problem | AVIP: 9.55Control: 7.75 | p=.044 |

| 11. The clarity with which the treatment and guidelines were explained to you | AVIP: 9.42Control: 8.21 | p=.096 |

| 12. The ease of the steps you had to go through if you needed to ask for another appointment | AVIP: 8.66Control: 6.71 | p=.039 |

In bold, statistically significant results.

In terms of perceived level of anxiety during the surgical process, measured on a visual analogue scale from 0 to 10 points, the AVIP group showed better results with 4.6 points compared to 6.1 points in the control group (p=.037).

Of the patients in the AVIP group, 16.1% were satisfied with the application, while 83.9% were very satisfied. All patients would recommend the use of the AVIP application to other patients undergoing THA.

Major complications were one periprosthetic fracture in the control group and one deep vein thrombosis in the AVIP group. During follow-up, 4 unscheduled hospital visits were recorded in the AVIP group (3 generated via the application and one from the emergency department) and 6 in the control group (all generated from the emergency department) (p>.05). Of the 62 possible telematic visits scheduled in the AVIP group (those corresponding to the third and sixth month), 51 consultations were carried out in this way (82.25%), as different patients at some point opted for a face-to-face visit in the hospital consultation requested after telephone contact or via the AVIP application. We recorded a total of 24 contacts via the application in the ‘Contact your orthopaedic surgeon’ section. In 19 cases, the reason for these contacts was a question or query about the medical procedure: 16 of these were resolved remotely, and on 3 occasions we made an unscheduled appointment because the reason for the consultation required assessment of the patient face-to-face. We recorded 5 consultations for administrative reasons.

DiscussionIn recent years, the concept of digital health has become increasingly relevant in healthcare. It aims to increase patients’ participation in the healthcare process and improve their self-management skills.11,12 The aim of mHealth applications is to facilitate patients access to multimedia content that provides 24/7 care and information.19 In theory, this should lead to improved health outcomes by increasing the amount of information provided, while facilitating both communication and the doctor-patient relationship. All this should result in socio-economic cost savings.20 However, there is a lack of evidence on the effectiveness of the use of digital health applications in patients undergoing THA, more specifically, hip arthroplasty.21 Therefore, the aim of our study was to develop and evaluate the efficacy of the AVIP app, based on evidence-supported content, in clinical terms, on quality of life and quality of care in the follow-up of patients after primary hip replacement surgery.

As shown above, functional status and quality of life improved significantly in both groups compared to their status prior to the surgery.

However, there was no evidence of superiority for either group (Table 2). Several clinical trials available in the literature support the results presented in our series. In a randomised clinical trial of 59 patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty, Colomina et al.22 found no evidence of superior clinical and quality of life outcomes in favour of the conventional follow-up group (n=30) compared to a group of patients who were telemonitored (n=29). Similarly, Zhang et al.,23 in their randomised clinical trial compared 17 patients followed up using a mobile application with 14 patients followed up conventionally. Both groups experienced improved clinical and quality of life outcomes, with no evidence of superior outcomes in favour of either of the 2 groups studied. In a randomised clinical trial on 70 hip replacement patients (35 in each treatment group), Nelson et al.24 reported non-inferiority in clinical and quality of life outcomes in the group included in a telerehabilitation programme compared to the usual follow-up programme, with significant improvements at the end of follow-up in both treatment groups. Similarly, in knee replacement surgery, there are many studies available in the literature confirming non-inferiority of outcomes in patients monitored via multimedia applications.25–27

A systematic review by Gunter et al.,28 focusing on telemedicine, showed that complication rates after surgery did not differ between mHealth intervention and control groups in different patient populations. In our series, and in line with that review, we did not find a higher complication rate in any treatment group. The communication and virtual support provided by the AVIP application leads to a better doctor–patient relationship and feedback, which facilitates early detection of any complications or adverse events in the recovery process.

In the present study, the number of unplanned visits was similar in both treatment groups (p>.05), with 4 in the AVIP group and 6 in the control group. Colomina et al.22 report a reduction in the number of unplanned contacts after surgery in telemonitored patients, which can lead to significant savings for the healthcare system. At the end of follow-up, they estimated savings of between €109 and €126 per patient. This saving is also a consequence of the reduction in the number of face-to-face consultations for telemonitored patients: in our AVIP group, 82.25% of the visits were carried out remotely, which also means a reduction in hospital pressure, both in orthopaedic consultations and in the radiodiagnostics department of a tertiary hospital. In addition to the benefits for the healthcare system, telemonitored patients also benefit from reduced waiting times, unnecessary transport, and absenteeism.

Despite the difference in follow-up between the two groups, both the patients in the AVIP group and the control group patients reported high levels of satisfaction in the SUCE questionnaire (Table 3), and 100% of the patients who used the AVIP application were satisfied or very satisfied, and all recommended its use to other patients undergoing hip arthroplasty. Nelson et al.24 reported satisfaction of over 85% in both groups according to the Health Care Satisfaction Questionnaire. In our study, we found a superiority in the AVIP group in questions 10 and 12 of the SUCE questionnaire (p<.05) (Table 3), which asked about the level of “clinical information you received about your health problem” and “ease of the steps you had to go through if you needed to ask for another appointment”. We believe that these results are a consequence of the extensive evidence-based and easy-to-understand information available in the AVIP application that patients can easily access and the direct feed-back provided via the application to the surgical team, where doctors can arrange a face-to-face appointment at an early stage if necessary.

In addition, we believe that the pre- and postoperative recommendations available in the AVIP application offered the patients in this group better training in the use of arthroplasty, and thus were able to walk independently sooner. This is demonstrated in our study, where patients included in the AVIP group show superior walking ability at the end of the first month of follow-up according to the results obtained from the Functional Gait Assessment Scale17 (p=.03).

Preoperative preparation or prehabilitation has a positive effect on patients’ ability to cope with the postoperative process. Well-structured preoperative information about the surgery and the whole care pathway around the procedure supports patients’ understanding of their physical situation, reduces anxiety and creates appropriate expectations of the final outcome.10,29 As a result of the extensive information about the surgical process and physical preparation for surgery, available in the “Before my surgery” section of the AVIP application, we observed a lower level of anxiety perceived by patients in the AVIP group compared to the control group, with 4.6 points and 6.1 points (out of 10) respectively (p=.037), as well as better walking ability at the end of the first month, as reported earlier. In the literature consulted, only Doiron-Cadrin et al.30 studied the benefits of a tele-prehabilitation programme in hip and knee arthroplasty, and their results were consistent with those of the present study, both in terms of anxiety, functional recovery, and satisfaction.

Limitations of the study include the limited number of patients included, which may affect the statistical power of the reported results. In addition, the limited duration of the intervention and follow-up may underestimate long-term adverse effects. Finally, the lack of knowledge and access to the necessary technological resources by some patients may have limited the conduct of the study. Therefore, selection bias is a potential source of bias in this study, as patients who are unable to download or use the application are excluded from the preoperative phase, and the sample may not be representative of the general population, thus reducing the external validity of the study.

In contrast, the present project has several strengths: firstly, we highlight the prospective randomised design of the study including a control group, which allows a more rigorous evaluation of the results. Secondly, the sample studied covers a broad and heterogeneous age group, which is representative of the general population who are candidates for THA, and therefore we believe that the AVIP system could be applied to most of our patients. Finally, an effort was made to involve all professionals involved in the surgical and postoperative hip arthroplasty process, including orthopaedic nurses, rehabilitation specialists, and physiotherapists. This aspect is of great importance, as the lack of collaboration between professionals and teams has been identified as a recurrent obstacle.31

In conclusion, this study shows that the patients included in the AVIP project who were telemonitored using an mHealth application obtained clinical and quality of life outcomes that were not inferior to those obtained through conventional follow-up. All this with a high level of satisfaction with the care process and a low rate of complications.

For healthcare staff, the AVIP system simplifies and enables effective monitoring of the patients’ rehabilitation process, providing continuous information and training that is difficult to achieve in pre- and postoperative consultations, with time constraints.

Finally, the reduction of face-to-face appointments and unnecessary trips to the health centre could result in less overcrowded outpatient care with a hypothetical benefit in terms of both direct and indirect costs. Therefore, new lines of research are needed to analyse the potential cost benefits of using mHealth in the follow-up of prosthetic joint implants.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence i.

Ethical considerationsProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no human or animal experiments were performed in this study.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they followed their centre's protocols for the publication of patient data and that all patients included in the study were adequately informed and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients or subjects referred to in the article. This document is on file with the corresponding author.

FundingThis study was funded by the SECOT Foundation's “Proyectos de Iniciación a la Investigación” grant, which was awarded in 2021.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare. This study was carried out with the support of the SECOT Foundation “Iniciación a la Investigación 2021”.

The authors would like to thank the SECOT Foundation for the grant “Iniciación a la Investigación 2021”, without which this project would not have been possible.