Knowing that COVID-19 is transmitted from person to person, is associated with high morbidity, and is potentially life-threatening can arouse intense and even overwhelming emotions in surgical teams directly involved in patient care. These include feelings of sadness for patients who succumb to the disease, helplessness in the absence of specific treatment, fear of contagion, guilt for possibly transmitting the infection to family members and other patients, challenge at having to understand new clinical protocols and apply them in a particular setting, anxiety due to information overload and constant changes, uncertainty in the face of an unknown situation, insecurity at having to work in unfamiliar services or units, and vulnerability due to the shortage of some personal protective equipment. Despite the common belief that healthcare workers have resources to deal with this situation and that working harder is sufficient, evidence has shown that up to 71% of professionals exhibit stress, 50% depression, 44% anxiety, and 34% insomnia, while consumption of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs has increased and chronic processes have been aggravated in this collective1. Stress and anxiety have a negative effect on clinical performance2.

Among professionals on the front line of care, conversations are a good method for improving teamwork and communication in the surgical suite during COVID-19. Sharing accurate information, showing an interest in their peers, offering mutual support and planning procedures can help clinicians reduce stress and strengthen the professional community. These strategies, when implemented effectively, can also improve patient outcomes3. However, although frameworks for analysing performance after real or simulated events have been developed, they are often more educational than practical in both their duration and focus, and are unsuitable for the clinical setting. Very few recommendations on how to guide conversations during daily practice and especially during a pandemic have been published.

We propose a tool in the form of structured conversations than can provide hospital staff with psychological help, support surgical teams involved with COVID-19 patients, and facilitate care excellence, and we discuss our experience with its use.

These conversations are based on the key elements of the briefings held after simulated or real cases, such as establishing and maintaining a participatory environment, structuring the conversation in an organized manner, and achieving or sustaining good performance in the future. Performance analysis is based on key elements used in organizational change, such as recognizing the strengths that can be relied on in times of uncertainty and challenge, and reflecting on changes that can be incorporated in the future4.

Briefings and the daily flow of information, albeit with some variations, usually take place at the start and end of the day, the shift, or a major activity (such as donning and doffing PPE or performing endotracheal intubation), and are also held throughout the day to reflect on the day’s events (such as the management of an intestinal obstruction in a COVID positive patient) or to enquire about a personal situation (such as the illness of a loved one). Debriefings are held at the end of the day, shift or activity. These conversations are designed to explore aspects of teamwork, what should be maintained, what needs to be improved, and to get an idea of what needs to be done.

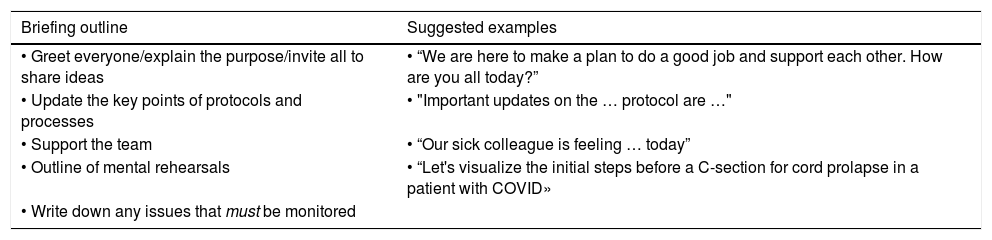

The elements of the briefing are shown in Table 1. We would emphasize the importance of creating a conversational framework, updating processes and protocols, discussing the availability and reuse of equipment, and reorganising the work according to the changes detected. Another key element is taking the people involved in this work into consideration, listening to innovations, doubts and solutions, and asking the team how to support them. It is essential to offer the possibility of mentally rehearsing the new procedure to be performed. This is not a simulation, but involves going through what needs to be done with the team both mentally and out loud, and increases well-being and boosts self-confidence. Finally, it is very useful for all professionals involved to agree on a plan.

Outline of learning conversations at the start and end of the day, shift or care activity.

| Briefing outline | Suggested examples |

|---|---|

| • Greet everyone/explain the purpose/invite all to share ideas | • “We are here to make a plan to do a good job and support each other. How are you all today?” |

| • Update the key points of protocols and processes | • "Important updates on the … protocol are …" |

| • Support the team | • “Our sick colleague is feeling … today” |

| • Outline of mental rehearsals | • “Let's visualize the initial steps before a C-section for cord prolapse in a patient with COVID» |

| • Write down any issues that must be monitored |

| Outline for conversations between colleagues | Suggested examples |

|---|---|

| • Establish the context | • “This is a difficult situation. Do you have a moment to chat? No problem if now is not a good time”. |

| • Share challenges | • "What challenges have you faced today?" |

| • Identify what worked | • "What has helped?" |

| • Offer support | • "How can I help you?" |

| Debriefing outline | Suggested examples |

|---|---|

| • Greet everyone/explain the purpose/invite all to share ideas | • "Thanks for coming. We are here to talk about our successes and challenges today” |

| • Note down successes and generate ideas for improvement | • «Was there something that went well today and that we want to repeat and share with other shifts” |

| • Support the team | • "What was the most difficult situation today?" |

| • Identify elements of action | • "What critical information do we need to communicate to the management/other shifts now?" |

| • Write down any issues that must be monitored |

Adapted with permission from: Center for Medical Simulation. Circle Up for COVID-19, 2020 [consulted 6 May 2020]. Available on: https://harvardmedsim.org.

The debriefing is a time to share success stories, explore the root cause of challenges, discuss what is needed and draft a plan to meet such challenges, following the outline provided in Table 1.

Formal or informal face-to-face, telephone or internet meetings often take place during or after the working day and are a source of support for professionals. The key elements proposed in Table 1 can guide these conversations. The main aim is to build resilience and help the team face challenges together. It is important to state the purpose of the conversation and ask permission to start it. Recognizing and validating emotions is often more effective than proposing solutions and trying to fix them.

Ideally, the conversation should be guided by a coordinator supported, if possible, by another professional who notes down the information obtained. The conversation will usually last from 5 to 10 min, and can be held in any clinical or surgical setting.

The difficulties most frequently encountered were starting the conversation, being present in the moment, being kind, and listening.

Taking a systematic approach to these conversation cycles has led to improvements in protocols and clinical practices, and facilitated the spread of these innovations around the hospital. Many professionals stated that they allowed them to evolve from an emotional state dominated by fear and anger (in which they often repeated many of the negative messages received, were infected with other people’s negative emotions, and felt that they had reached an impasse) to a state of learning (with greater situational awareness, awareness of their own emotions, and being able to focus on how to act and contribute). This coincided with other findings in which the briefings and debriefings promoted well-being and resilience in the surgical suite, and made clinicians feel more competent and in control of the situation5.

FundingThe authors declare that they have no financial relationship with any commercial company marketing products or services related to the simulation. Hospital Virtual Valdecilla is affiliated with the Center for Medical Simulation, Boston, USA. Both are non-profit educational institutions that offer tuition-based training programs.

No funding was received

Please cite this article as: Maestre JM, Rábago JL, del Moral I. Una herramienta para apoyar el trabajo de los equipos quirúrgicos y afrontar la COVID-19. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2020;67:355–356.