ANCA vasculitis has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality, high disease burden, and organ damage, especially renal.

ObjectivesTo determine factors associated with end-stage kidney disease at hospital discharge in microscopic polyangiitis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis patients, to characterize our population, hospitalization causes, treatment received, and complications during stay.

Materials and methodsAdults with previous or new diagnosis of microscopic polyangiitis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis who required hospitalization between January 01, 2013, and April 30, 2021, were included. Association with end-stage kidney disease development was evaluated by Pearson’s Chi2 (χ2) or Fisher’s test, and Student’s t or Mann–Whitney U test according to the nature of the variables. Exploratory multivariate models were made including factors associated with end-stage kidney disease.

ResultsForty-three patients were included, microscopic polyangiitis 55.8, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis 44.25. Twelve patients (27.9%) developed early end-stage kidney disease. High blood pressure, high urea nitrogen levels on admission, as well as pulmonary oedema, and Five Factor Score >1 entailed a higher risk. In contrast, normal kidney function on admission was a protective factor. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and arterial hypertension on admission were associated with end-stage kidney disease. In adjusted exploratory models according to vasculitis type, Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score, diffuse alveolar haemorrhage, and plasma exchange use were identified as factors to include in multivariate models in multicentre studies.

Conclusion88% of patients had renal involvement and 27.9% developed end-stage kidney disease. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and arterial hypertension on hospital admission were associated with early development of end-stage kidney disease while normal renal function on admission was a protective factor for this outcome.

Las vasculitis ANCA ocasionan aumento de la morbimortalidad, alta carga de enfermedad y daño de órgano, especialmente renal.

ObjetivosDeterminar los factores que se asocian con el desarrollo de insuficiencia renal crónica terminal al egreso hospitalario en los pacientes con granulomatosis con poliangitis y poliangitis microscópica, caracterizar la población y describir las causas de hospitalización, los tratamientos recibidos y las complicaciones presentadas durante la estancia hospitalaria.

Materiales y métodosSe incluyeron los pacientes con 18 o más años con diagnósticos previos o nuevos de poliangitis microscópica o granulomatosis con poliangitis que requirieron hospitalización entre 1-01-2013 y 30-04-2021. La asociación con el desarrollo de insuficiencia renal crónica se evaluó con Chi2 de Pearson o prueba exacta de Fisher y t de Student o U de Mann Whitney, de acuerdo con la naturaleza de las variables. Se hicieron modelos multivariantes exploratorios que incluyeron los factores asociados con insuficiencia renal crónica terminal con p < 0,15 en el análisis bivariante o con plausibilidad biológica.

ResultadosLa cohorte está constituida por 43 pacientes, 55,8% con poliangitis microscópica y 44,2% con granulomatosis con poliangitis. Doce pacientes (27,9%) desarrollaron insuficiencia renal crónica durante la hospitalización. Aquellos con hipertensión arterial y retención de azoados al ingreso, edema pulmonar yFive Factor Score ≥ 1 tuvieron más riesgo de egresar con ese desenlace. La función renal normal al ingreso fue un factor protector. La glomerulonefritis rápidamente progresiva y la hipertensión arterial al ingreso se asociaron con insuficiencia renal crónica terminal en los modelos exploratorios ajustados por el tipo de vasculitis, puntaje del Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score, presencia de hemorragia alveolar difusa y uso de recambios plasmáticos. Estas variables se identificaron como factores para incluir en modelos multivariante en estudios multicéntricos.

ConclusionesEl 88,8% de los pacientes con vasculitis asociada a ANCA tuvieron compromiso renal y el 27,9% de ellos desarrollaron insuficiencia renal crónica terminal durante la hospitalización. La glomerulonefritis rápidamente progresiva y la hipertensión arterial al ingreso al hospital se asociaron con el desarrollo de este desenlace, mientras que la función renal normal al ingreso fue un factor protector.

Systemic vasculitis is characterized by vascular inflammation and endothelial injury, potentially causing damage to any organ.1–5 According to the nomenclature proposed by the Chapel Hill consensus, small vessel vasculitis can be classified as either associated or not associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA).6 The former category includes microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). These conditions are associated with a significant disease burden, impaired quality of life, organ damage—particularly renal damage—disability, and increased mortality.1,2

The behavior of ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) has been well-characterized in European, Asian, and American populations.1,2,7–10 In Hispanic populations with AAV residing in Chicago, more severe manifestations, greater renal involvement, acute renal failure requiring dialysis, and higher scores on the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS)11 and the vasculitis damage index (VDI)12 have been observed, both at diagnosis and during disease progression.13

However, fewer studies assess the behavior of vasculitis in Latin America,14–17 and none have explored the factors associated with the early development of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Ochoa et al.14 described 857 Colombian patients with vasculitis diagnosed between 1945 and 2007, with AAV accounting for 15.7% of cases. Fernández-Ávila et al.15 described 106 Colombian subjects with AAV diagnosed between 2005 and 2017 but did not report factors associated with ESRD.

ESRD is a major component of organ damage in patients with AAV.18 In six clinical trials19–24 conducted by the European Vasculitis Study Group (EUVAS),18 approximately 8% of individuals developed early ESRD, with a higher frequency observed in those with MPA. During follow-up, patients with myeloperoxidase (MPO)-ANCA developed ESRD more frequently than those with proteinase 3 (PR3)-ANCA (42.5% vs. 27.9%).18

Several authors have identified important differences in the behavior of patients with AAV in clinical trials compared to those in observational studies.25,26 While factors associated with long-term ESRD have been studied in various populations, those associated with its early development remain less explored,4,8,27 and to date, such factors have not been evaluated in the Colombian population.

The purpose of this study was to identify the factors associated with the development of ESRD during hospitalization and to characterize the clinical course of inpatients with GPA and MPA in a high-complexity Colombian institution.

Patients and methodsMain objectiveTo identify the factors associated with ESRD and hospital discharge in patients with GPA and MPA. ESRD was defined by histological or ultrasound evidence of chronicity and the need for indefinite dialysis at the time of hospital discharge.

Secondary objectivesTo characterize the patient population and describe the treatments administered and complications experienced during hospitalization. A convenience sample was used, including all patients aged 18 years or older with a diagnosis of new or relapsed GPA or MPA,6 hospitalized between January 1, 2013, and April 30, 2021. Incomplete records and patients admitted with ESRD, neoplasms, or active pulmonary tuberculosis were excluded. Subjects were identified in the hospital database using ICD-10 codes M31.30, M31.31, and M31.7. Data were collected through a review of medical records and entered into a structured form using Google Forms (version 2021).

The variables studied included age, sex, disease duration, clinical manifestations at diagnosis and during disease progression (hypertension [HT], hematuria, proteinuria, nitrogen retention, sinusitis, rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis [RPGN], nasal septum perforation, epistaxis, bronchitis, otitis, pneumonia, pulmonary nodules, pleural effusion, tracheobronchial stenosis, alveolar hemorrhage, scleritis, orbital pseudotumor, peripheral neuropathy, cerebral infarction, pachymeningitis, purpura, digital necrosis, ulcers, livedo reticularis, venous and arterial thrombosis, ICU admission, ESRD, and death), treatment with methylprednisolone pulses, prednisolone, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab, serum levels of C3 and C4, Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS),11 and the Five Factor Score (FFS).26

The diagnosis of MPA and GPA was made based on the clinical judgment of the medical team and antibody seropositivity. RPGN was defined as a rapid decline in glomerular filtration rate (at least 50%) over a few days to three months, and when renal biopsies were available, by the presence of extensive extracapillary proliferation. Alveolar hemorrhage was defined by new pulmonary infiltrates, a decrease of 2 g or more of hemoglobin within the previous 48 h, with or without hemoptysis, evidence of bleeding unexplained by other causes, or the presence of more than 20% hemosiderophages in bronchoalveolar lavage. Methylprednisolone pulses were defined as doses of 125 mg/day or higher.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables are presented as absolute frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables are shown as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges. The association between categorical variables and ESRD was assessed using Pearson’s chi-square (χ2) or Fisher’s exact test. The association between continuous variables and the primary outcome was evaluated using Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U tests, depending on the distribution of the data.

In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, variables associated with the primary outcome that had significant odds ratios (ORs) or p-values <0.15 (according to the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for logistic regressions) were included, along with variables considered biologically plausible. Several exploratory models were created to identify potential factors associated with ESRD, which could apply to multivariate models in larger populations. In these exploratory models, variables independently associated with the outcome (HT and RPGN at admission) were adjusted for those meeting the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit criterion (type of vasculitis [MPA vs. GPA], diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, BVAS score ≤15 vs. > 15, and plasma exchange usage). Collinearity was determined using clinical criteria; variables identified as collinear were excluded from the models. Analyses were performed using SPSS software version 22, licensed to Hospital Pablo Tobon Uribe.

Ethical considerationsThis study posed no risk to the patients, and therefore, informed consent was not required. However, all participants signed habeas data forms. The protocol was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of Hospital Pablo Tobon Uribe.

In compliance with Resolution 008430, Article 11, of October 4, 1993, this research meets the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Colombia’s criteria for risk-free research, as it did not involve intentional modification of participants' biological, physiological, psychological, or social variables.

The ethical principles guiding the research adhere to the Nuremberg Code (1947), the Declaration of Helsinki (1964, amended in Tokyo in 1975), the International Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences and World Health Organization, 1982), and Colombia’s Law 23 of 1981. These guidelines emphasize the principles of respect for autonomy, beneficence/non-maleficence, and justice.

The researchers affirm that confidentiality was maintained, and the data was used exclusively for the purposes outlined in the study, with prior approval from the Hospital Pablo Tobon Uribe Ethics Committee. All data will be stored in a secure database with restricted access for the study’s researchers.

ResultsThe population consisted of 43 subjects, primarily women, with 63% having a new diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis. MPA was more prevalent than GPA. ANCA were positive in 98% of subjects (50% MPO and 48% PR3). Only 5 subjects (12%) showed complement consumption: three with hypocomplementemia C4 (7.3%) and two with hypocomplementemia C3 (4.9%). A total of 48.8% of individuals exhibited nitrogen retention during hospitalization. Among them, 34.1% were admitted with a clinical diagnosis of RPGN, 53.4% had HT on admission, 34.1% microscopic hematuria, and 88.4% proteinuria (mean: 742 mg/day, SD: 570, range: 153–2230). Twelve patients (27.9%) progressed to ESRD, and one subject (2.3%) died (Table 1).

Population of patients with MPA and GPA hospitalized between 2013 and 2021.

| Full population (n = 43) | ESRD (n = 12) | No ESRD (n = 31) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female/male) | 26 (60.5%)/17 (39.5%) | 66/33% | 42/58% | 0.556 |

| Age at hospital admission (years) | 59 (IQR: 18), 16−84) | 57 (18−84) | 62.5 (31−78) | 0.87 |

| Time between diagnosis and hospitalization (months)a | 22.37 (SD: 48.4), 0−216 | 13.6 (1−48) | 76.7 (3−216) | 0.61 |

| Hospitalization time (days) | 36 (SD: 29.8), 10−82 | 21.5 (4–82) | 6.5 (2−49) | 0.49 |

| Type of vasculitis | 0.11 | |||

| MPA, n (%) | 24 (55.8%) | 75% | 48% | |

| GPA, n (%) | 19 (44.2%) | 25% | 52% | |

| Type of diagnosis | 0.28 | |||

| New, n (%) | 27 (63%) | 50% | 68% | 0.71 |

| Relapse, n (%) | 16 (37%) | 50% | 32% | |

| ANCA (n = 42) | MPO 21 (50%), PR3 20 (47.6%) | MPO 75%, PR3 25% | MPO 58%, PR3 42% | 0.432 |

| BVAS | 14.78 (SD: 6.76), 0−26 | 20.3 (16−25) | 733 (2−14) | 0.125 |

| FFS on admission | 1 (RIC 1), 0−2 | 0.002 | ||

| FFS greater than 1 | 0.002 | |||

| High blood pressure on admission | 53.5% | 92% | 38.7% | 0.002 |

| Normal renal function on admission | n = 22 (51.2%) | 0 | 21 (68%) | <0.001 |

| Nitrogen retention during hospitalization | n = 21 (48.8%) | 100% | 32% | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl), highest value | 1.27; IQR: 1.07 (0.56−7.7) | 1.39; IQR: 6.5 (0.7−7.2) | 1.35; IQR: 4.2 (0.8−5) | <0.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dl), highest value | 43; RIC: 55 (10−162) | 58; RIC: 48 (24−72) | 35; RIC: 54 (19−73) | <0.001 |

| Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis on admission | 15 (34.1%) | 82% | 16% | <0.001 |

| ESRD | 12 (27.9%) | |||

| Admission to ICU | 15 (34%) | 33% | 35.4% | 0.89 |

| Requirement for mechanical ventilation | 10 (23.2%) | 16.6% | 25.8% | 0.52 |

| DAH | 13 (30%) | 50% | 25% | 0.087 |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 10 (23%) | 0 | 32% | 0.025 |

| Pre-admission medications | ||||

| Methotrexate | 3 (6.9%) | 0 | 9% | 0.26 |

| Azathioprine | 6 (13.8%) | 18% | 12.9% | 0.66 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 5 (34.8%) | 41.6% | 32.2% | 0.56 |

| Rituximab | 8 (18.6%) | 16.6% | 19.3% | 0.84 |

| Treatment during hospitalization | ||||

| Methylprednisolone | 27 (62.7%) | 75% | 58% | 0.3 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 25 (58%) | 66% | 54.8% | 0.48 |

| Rituximab | 10 (23.2%) | 25% | 22.5% | 0.86 |

| Plasma exchanges | 5 (11.6%) | 25% | 6.45% | 0.089 |

ESRD: end-stage renal disease; MPA: Microscopic Polyangiitis; GPA: Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis; ANCA: Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies; MPO: Myeloperoxidase; PR3: Proteinase 3; BVAS: Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score; FFS: Five-Factor Score; ICU: intensive care unit; DAH: diffuse alveolar hemorrhage.

Seventeen subjects (39.5%) underwent renal biopsy. Ten biopsies showed extracapillary proliferation (58.8%), observed in 50% of glomeruli (IQR: 64.75; range: 0–86%). Seven individuals had fibrinoid necrosis (41.1%), seen in 19.9% of glomeruli (SD: 27.38). A total of 64.7% of biopsies showed tubular involvement, affecting 25% of nephrons (IQR: 40; range: 20–70), with no significant difference between patients with MPA and GPA (p = 0.21). Five biopsies (29.4%) showed vasculitis, observed in 13.22% of glomeruli (SD: 26.7%), and direct immunofluorescence was negative in 76.4% of these samples.

Nineteen individuals (44%) had upper respiratory tract (URT) involvement: 15 had sinusitis (35%), 12 epistaxis (28%), 7 nasal septum perforation (16%), and 6 otitis media (14%). Thirteen subjects (30%) presented with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), 12 pulmonary nodules (27.9%), 10 pneumonia (23%), 8 bronchitis (19.5%), 4 tracheobronchial stenosis (9.3%), and 3 pulmonary fibrosis (7.51%). Twelve patients (27%) had peripheral neuropathy: 8 sensory-motor neuropathy (18%), and 4 pure motor (9%). Ten subjects (23.2%) had purpura, 2 livedo reticularis (4.4%), and one digital necrosis (2.2%). Nine subjects (20.9%) had scleritis, and one (2.8%) orbital pseudotumor. Six patients (14%) developed thrombosis during hospitalization: 4 arterial (8.8%) and 2 venous (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fifteen patients (34%) required treatment in the ICU, 10 of whom (66%) needed mechanical ventilation (23.2% of the overall population): 8 were treated with invasive ventilation (18.6%), and 2 with non-invasive ventilation (4.65%). One patient developed pneumothorax (10%), but none of the patients on mechanical ventilation died. The average ICU stay was 13.5 days (IQR: 16.8 [3–54]), and the average duration of mechanical ventilation was 9.4 days (SD: 6.58 [2–21]). The main reasons for ICU admission were DAH (6 cases, 40% of ICU admissions, 13.9% of the overall population), infection (5 cases, 33% of ICU admissions, 11.6% of the population), pulmonary edema (2 cases, 13.3% of ICU admissions, 4.65% of the population), and surveillance following reconstructive surgery for tracheal stenosis (2 cases, 13.3% of ICU admissions, 4.65% of the population) (Fig. 3).

Thirteen individuals (30%) had confirmed infections during hospitalization, with 12 of them (92%) showing positive cultures. In an additional 19 patients (44%), infections were suspected based on paraclinical studies. The most common infection was URT (n = 9, 21% of the population, 69.2% of infections), followed by bacteremia (n = 3, 6.9% of the population, 23% of infections), sepsis (n = 3, 6.9% of the population, 23% of infections), urinary tract infections (n = 3, 6.9% of the population, 23% of infections), and skin and soft tissue infections (n = 1, 2.3% of the population, 7.6% of infections). The identified pathogens included Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecium (pyelonephritis), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (bacteremia, soft tissue infection, tracheobronchitis), Staphylococcus aureus (sinusitis, endocarditis, pyomyositis), and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (two cases).

Before hospitalization, 15 subjects (34.8%) had received cyclophosphamide (cumulative dose: 2000 mg, IQR: 525, range: 500–4000), 8 (18.6%) rituximab (cumulative dose: 2000 mg, IQR: 375, range: 1000–2000), 6 azathioprine (13.8%), and 3 methotrexate (6.9%). During hospitalization, 27 patients received methylprednisolone (62.7%), with a cumulative dose of 1500 mg (IQR: 0), ranging from 250 to 5000 mg. Twenty-five individuals were treated with cyclophosphamide (58%), with a cumulative dose of 500 mg (IQR: 525), ranging from 300 to 1000 mg, and 10 received rituximab (23.2%), with a cumulative dose of 1500 mg (SD: 550), ranging from 1000 to 2000 mg. Five subjects (11.6% of the overall population and 33% of those requiring ICU management) underwent plasma exchange, with an average of 8 sessions (SD: 3.4), ranging from 5 to 13.

Univariate analysisThe variables that were significantly associated with the ESRD outcome at hospital discharge were hypertension (p = 0.002), RPGN (p < 0.001), basal elevation of creatinine (p < 0.001) or urea nitrogen (p < 0.001), lung edema (p = 0.02) and FFS higher than 1 (p = 0.002). The normal renal function for age at admission acted as a protective factor for this outcome (p < 0.001). The patients with MAP (OR: 3.2; 95% CI: 0.72; 14, p = 0.13), BVAS score ≥ 15 (OR: 3.2; 95% CI: 0.72; 14; p = 0.125), who presented DAH (OR: 3.42, 0.83; 14, p = 0.087), required plasma exchanges (OR: 4.83; 95% CI: 0.69; 33; p = 0.11) or mechanical ventilation (OR: 7.7; 95% CI: 0.21; 22.6; p = 0.27) had a higher risk of developing ESRD, although the differences were not statistically significant. Complement consumption was not associated with the development of ESRD (p = 0.125), as well as hypocomplementemia C3 (p = 0.35) or C4 (p = 0.247) (Table 2).

Factors associated with early development of ESRD.

| Crude OR (95% CI), p | Adjusted OR (95% CI), p | |

|---|---|---|

| High blood pressure | 17.41 (1.98; 152), 0.01 | 17.4 (1.4−213), 0.025 |

| RPGN on admission | 2.25 (3.6; 1.37), 0.001 | 22 (2.84−180), 0.003 |

| Type of vasculitis (MPA/GPA) | 3.2 (0.72; 14), 0.13 | |

| Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage | 3.42 (0.83; 14), 0.087 | |

| Plasma exchanges | 4.83 (0.69; 33), 0.11 | |

| BVAS ≥ 15/<15 | 3.2 (0.72; 14), 0.125 | |

| Bronchitis | 3.5 (0.38; 32), 0.27 | |

| Pulmonary nodules | 2.44 (0.59; 10), 0.22 | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 4.5 (0.49; 41), 0.18 | |

| Cutaneous vasculitis | 1.39 (0.28; 6.75), 0.68 | |

| Indication for treatment in ICU | 0.9 (0.22–3.7), 0.89 | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 7 (0.21; 22.6), 0.27 | |

| Admission to ICU due to alveolar hemorrhage | 3.11 (0.53; 18), 0.2 | |

| Time in ICU (≥7 days/ <7 days) | 3.11 (0.53; 18.22), 0.2 | |

| 24-hour proteinuria ≥ 500 mg/<500 mg | 3.11 (0.53; 18.22), 0.2 |

ESRD: end-stage renal disease; OR: odds ratio; RPGN: Rapidly Progressive Glomerulonephritis; MPA: Microscopic Polyangiitis; GPA: Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis; BVAS: Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score; ICU: intensive care unit.

The presence of AHT (OR: 17.4; 95% CI: 1.4-213; p = 0.025) and RPGN (OR: 22; 95% CI: 2.84-180,; p = 0.003) was independently associated with the outcome ESRD at hospital discharge (Table 2).

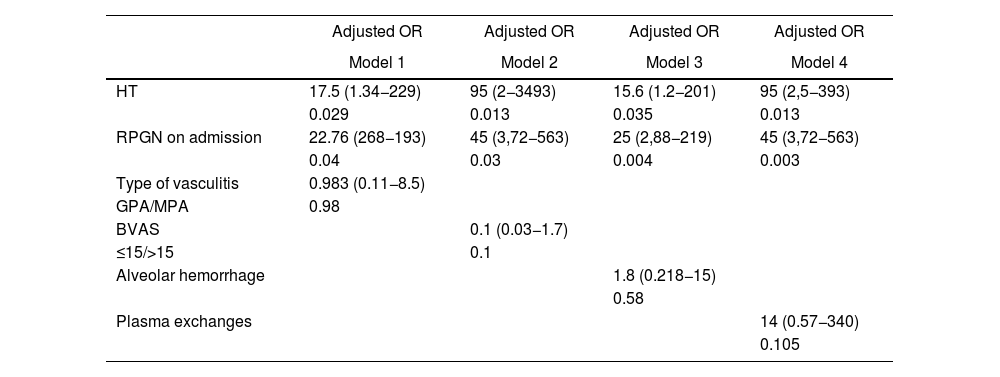

Exploratory models were made adjusting the two variables independently associated with ESRD with each of the variables that met three conditions: the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit criterion, biological plausibility and support in the literature. They were then adjusted for type of vasculitis, BVAS score, HAD, and use of plasma exchanges. In the four exploratory adjusted models, GMNRP and HTA at hospital admission behaved as factors independently associated with ESRD during hospitalization (Table 3).

Factors associated with early development of ESRD: exploratory models.

| Adjusted OR | Adjusted OR | Adjusted OR | Adjusted OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| HT | 17.5 (1.34−229) | 95 (2−3493) | 15.6 (1.2−201) | 95 (2,5−393) |

| 0.029 | 0.013 | 0.035 | 0.013 | |

| RPGN on admission | 22.76 (268−193) | 45 (3,72−563) | 25 (2,88−219) | 45 (3,72−563) |

| 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.004 | 0.003 | |

| Type of vasculitis | 0.983 (0.11−8.5) | |||

| GPA/MPA | 0.98 | |||

| BVAS | 0.1 (0.03−1.7) | |||

| ≤15/>15 | 0.1 | |||

| Alveolar hemorrhage | 1.8 (0.218−15) | |||

| 0.58 | ||||

| Plasma exchanges | 14 (0.57−340) | |||

| 0.105 |

ESRD: end-stage renal disease; OR: odds ratio; HT: hypertension; RPGN: rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis; MPA: microscopic polyangiitis; GPA: granulomatosis with polyangiitis; BVAS: Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score.

Patients with a clinical diagnosis of RPGN, HT, and nitrogen retention upon admission who developed pulmonary edema and had a FFS ≥ 1 were at a higher risk of being discharged with ESRD, whereas normal renal function at admission served as a protective factor against this outcome. A clinical diagnosis of RPGN and HT at admission were independently associated with the early development of ESRD in exploratory models adjusted for vasculitis type, BVAS score, presence of ADH, and use of plasma exchange.

To date, the factors associated with the early development of ESRD in patients with AAV have not been assessed in the Colombian population. In European, Asian, and American populations, the progression of ANCA-associated vasculitis has been more thoroughly characterized.1,2,7–10 In Northern Europe and America, the disease typically presents with an earlier onset (between 50 and 70 years), severe and abrupt renal involvement, a higher frequency of pulmonary nodules or cavitations, and a higher incidence of PR3-ANCA. In contrast, in Asia and Southern Europe, renal involvement is often more insidious, with less pulmonary involvement, and rarely upper respiratory tract manifestations.1,2,7–10

Sreih et al.13 compared the clinical characteristics of 23 Hispanic and 35 Caucasian patients with AAV living in Chicago. The Hispanic group exhibited more severe manifestations, including a higher frequency of renal involvement (85% vs. 48%, p = 0.01), acute renal failure requiring dialysis, and higher BVAS and damage index (VDI) scores both at diagnosis and during follow-up.

Few studies have examined the behavior of vasculitis in Latin America,14–17 and none have explored the factors associated with the early development of ESRD. Cisternas et al.16 described the clinical manifestations of 123 Chilean subjects with AAV. In individuals with MPA, the most frequent manifestations were renal (68%), peripheral nervous system (57%), cutaneous (32%), and DAH (28%). In patients with GPA, renal affection was the most common (78%), followed by DAH (62%). In a series of 47 Argentine patients with AAV, 53% had renal involvement, with 35.3% having MPA and 30% having GPA. DAH occurred in 29.8% of cases, with 53% of MPA patients and 25% of GPA patients affected. Mortality was higher in subjects with MPA (p = 0.011) and in those older than 55 years (p = 0.029).17

Ochoa et al.14 described 857 Colombian patients with vasculitis diagnosed between 1945 and 2007; of these, 42% had small vessel involvement, most commonly Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children, while AAV accounted for 15.7% of cases. The most frequent conditions were Takayasu arteritis, Buerger's disease, cutaneous vasculitis, polyarteritis nodosa, and GPA. Fernández-Ávila et al.15 reported on 106 Colombian subjects with AAV diagnosed between 2005 and 2017. The most common conditions were GPA and MPA, with the most frequent presentation being renal (83.9%), of which 71.7% had proteinuria and 65% had creatinine levels greater than 1.5 mg/dL. Among 54 renal biopsies, pauci-immune necrotizing glomerulonephritis was found in 94.4%, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in two cases, and tubulointerstitial nephritis in one case. Pulmonary manifestations were observed in 43% of individuals, with DAH being the most common, followed by skin involvement (purpura and ulcers), upper respiratory tract (sinusitis and nasal septum perforation), and ocular affection (scleritis/episcleritis and uveitis).

ESRD is a major component of organ damage in patients with AAV.18 In the populations of six clinical trials,19–24 the EUVAS group18 found that approximately 8% of subjects developed early ESRD, with a higher frequency in those with MPA. During follow-up, individuals with MPO-ANCA developed ESRD more frequently than those with PR3-ANCA (42.5% vs. 27.9%).18 However, several authors note significant differences in the outcomes of patients with AAV in clinical trials versus observational studies, which should be considered when analyzing the prognosis and prognostic factors of these conditions.25,26

While several studies have investigated factors associated with long-term ESRD, few have focused on those linked to its early development. In a cohort of Chinese patients, age, infections, pulmonary involvement, and baseline renal function were identified as independent predictors of mortality, though factors related to early ESRD were not assessed.4 In Turkish and Italian cohorts,8,27 advanced age, dialysis urgency at admission, an FFS > 2, and the presence of extracapillary proliferation on renal biopsy were associated with ESRD.

Although AAVs can cause organ damage in the early stages of the disease,18,28 most studies focus on prognosis, organ damage, and long-term risk factors,8–10,13,27,29–31 with fewer examining early damage and its associated factors.32,33 Robson et al.18 assessed organ damage occurring within the first six months in 215 cases of MPA and 316 of GPA, finding that three of the six most frequent items of the VDI12 were renal: proteinuria, GFR less than 50 mL/min, and HT, with the first two being more common in MPA. In a cohort of 85 patients from the Netherlands, early dialysis requirement was associated with higher mortality.34 Toraman and Soysal Gündüz8 identified risk factors for ESRD like those in the current study, but with a higher frequency of this outcome (35% vs. 27.9%).

Patients with decreased glomerular filtration rate on admission required early dialysis, and those with an FFS ≥ 2 were at higher risk for ESRD. Solans-Laqué et al.9 observed a higher frequency of renal involvement, alveolar hemorrhage, and mortality in patients with MPO-ANCA, while those with PR3-ANCA had more relapses, ocular affection, and URT involvement. Renal affection was independently associated with mortality. In a cohort of 85 Korean subjects, early renal affection was more common in those with MPO-ANCA.10 Similarly, in the current cohort, individuals with MPA were at higher risk for developing ESRD than those with GPA, although this difference was not statistically significant.

Salmela et al.29 found that female sex was a predictor of renal survival, while individuals with a GFR less than 30 mL/min had a higher risk of long-term ESRD in a cohort of 53 children with MPA and GPA, where RPGM was the most frequent presentation (39 %). In the unadjusted analysis, a GFR below 30 mL/min, hypoalbuminemia, HT, neurological complications, and glomerular sclerosis were associated with ESRD. However, in the multivariate analysis, no prognostic factor emerged.29 Similarly, in the present study, HT and deterioration of renal function at hospital admission were associated with ESRD, but this was not the case for neurological complications or any histological parameters, likely due to the small number of renal biopsies.

Slot et al.34 observed that renal relapses were predictors of ESRD, while mortality was associated with age ≥65 years and dialysis dependence in a cohort of 85 patients with PR3-ANCA-associated vasculitis. Crnogorac et al.30 showed that the BVAS score, baseline creatinine, and hemoglobin were associated with the development of ESRD, while Tang et al.3 found that age over 65 years and creatinine greater than 5.65 mg/dL were linked to higher mortality. In the current study, neither sex nor age at presentation were identified as factors associated with ESRD during hospitalization.

In several AAV cohorts, the FFS was associated with the development of ESRD.8,10,35 Toraman and Soysal Gündüz8 found that baseline renal function and an FFS ≥ 2 at diagnosis were prognostic factors for this outcome. In a cohort of 103 Chilean patients, an FFS ≥ 1 was associated with early mortality but was not evaluated as a factor related to ESRD.35 In our study population, an FFS greater than one point was associated with ESRD during hospitalization in the univariate analysis, but not in the adjusted analyses, likely due to the small sample size and limited number of outcomes. The BVAS score has been linked to poor prognosis in Chinese and European AAV patients.4,36–38 In a cohort from the Netherlands, patients with MPO-ANCA had a higher BVAS score and a greater incidence of ESRD than those with PR3-ANCA,36 which is like observations in a Swedish population with AAV.39 However, this association has not been consistently found in other studies. In an Argentine cohort,17 the BVAS score was not a poor prognostic factor, while in the present study, neither the type of AAV nor the ANCA subclass differed between those who developed ESRD during hospitalization and those who did not (p = 0.1).

Alveolar hemorrhage has been associated with increased mortality in several studies3,35 but does not appear to be linked to the development of ESRD. In this study, patients with DAH had a higher risk of developing ESRD during hospitalization, though the association was not statistically significant. The role of renal histological findings as prognostic factors for AAV is limited by the small number of biopsies included in studies. In several European cohorts,27,29,31,40,41 a higher risk of ESRD was observed in subjects with crescentic and sclerotic forms compared to those with focal and mixed forms. The percentage of sclerotic31 and crescentic glomeruli41 has been identified as a predictor of poor prognosis. In the current cohort, the percentage of crescentic glomeruli, necrosis, or tubular involvement was not statistically associated with the development of ESRD during hospitalization, likely due to the small number of renal biopsies.

Sreih et al.13 found that Hispanics with AAV had greater severity, BVAS, organ damage, renal involvement, and dialysis requirements compared to Caucasians, but they did not explore the factors associated with these outcomes. Similarly, renal affection is common among subjects with AAV in several Latin American populations,14–17,35,42–47 but these studies did not examine the factors associated with ESRD in the early stages of the disease. In a cohort of 62 Mexican patients, dialysis requirement at admission and proteinuria were associated with long-term ESRD, while age and infections were linked to higher mortality.31 Like other Latin American cohorts, renal involvement in this group was frequent and severe: 48.8% of patients had nitrogen retention at some point during hospitalization, 34% suffered from RPGN, and 27 % developed early ESRD.

Several authors have studied the role of complement consumption as a prognostic factor in AAV. Toraman and Soysal Gündüz8 found that patients with low C3 levels had lower remission rates, while Fukui et al.48 observed that low C3 levels were associated with dialysis requirement and worse survival rates. Other studies have also linked low C3 levels to a higher risk of renal involvement, ESRD, mortality, and relapse.4,5,20 In the present study, however, C3 and C4 levels were not associated with the development of ESRD. This may be explained by the fact that these levels were not routinely assessed or by the possibility that such an association does not exist in the studied population.

Neumann et al.49 assessed clinical and histological factors that predict early and late outcomes in an Austrian cohort of AAV patients requiring dialysis. They found that patients younger than 65 years and those with less glomerular sclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, and vascular damage were more likely to recover renal function. These findings were not observed in our population; however, like the current cohort, neither the type of AAV nor the ANCA subtype was associated with renal prognosis. The main difference with our cohort is that not all individuals with renal involvement required dialysis.

This study has several limitations: first, the small population size and the number of outcomes mean that the observed associations are imprecise,50 so the models adjusted for vasculitis type, BVAS score, DAH, and plasma exchange use are exploratory. Second, there is a reference bias, as our hospital specializes in highly complex care. Third, the patients studied represent the most severe cases of AAV. Fourth, the analysis is limited to the outcome of subjects at hospital discharge, so the associated factors are only applicable to the development of ESRD during this period. Fifth, due to the nature of the health system, follow-up after hospital discharge was not possible, so ESRD could not be defined according to the KDIGO guidelines.51 Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that some patients may have recovered renal function after discharge, although this is unlikely in patients with chronic findings in ultrasounds and renal biopsies.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the factors associated with the development of ESRD from hospitalization in a Latin American population with AAV. The exploratory analyses identify potential prognostic factors for the early development of this outcome.

In conclusion, 88.8% of patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis had some degree of renal involvement, and 27.9% developed end-stage renal disease during hospitalization. Those admitted with hypertension or rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis were at higher risk of being discharged with end-stage renal disease, while normal renal function at admission served as a protective factor against this outcome. Multicenter, prospective studies that include patients with a new diagnosis are needed to more accurately determine the factors associated with end-stage renal disease in our population.

FundingNone.

We would like to thank the patients for placing their trust in our rheumatology group. We also thank the institution for its commitment to high-quality care, research, and teaching. We are grateful to Neil Smith Pertuz Charris, MSc in epidemiology and rheumatologist, for his critical analysis of the study.