Post-chikungunya virus (CHIKV) chronic arthritis is a common complication of the acute infection caused by this virus, with high risk of progression to functional and quality of life sequelae.

ObjectiveTo identify the clinical and immunological characteristics, functional disabilities, and quality of life decline in a sample of Colombian patients with chronic arthropathy associated with chikungunya virus (CHIKV).

MethodsA group of 94 patients was evaluated in a City in Colombia during the CHIKV epidemics from 2014 to 2015

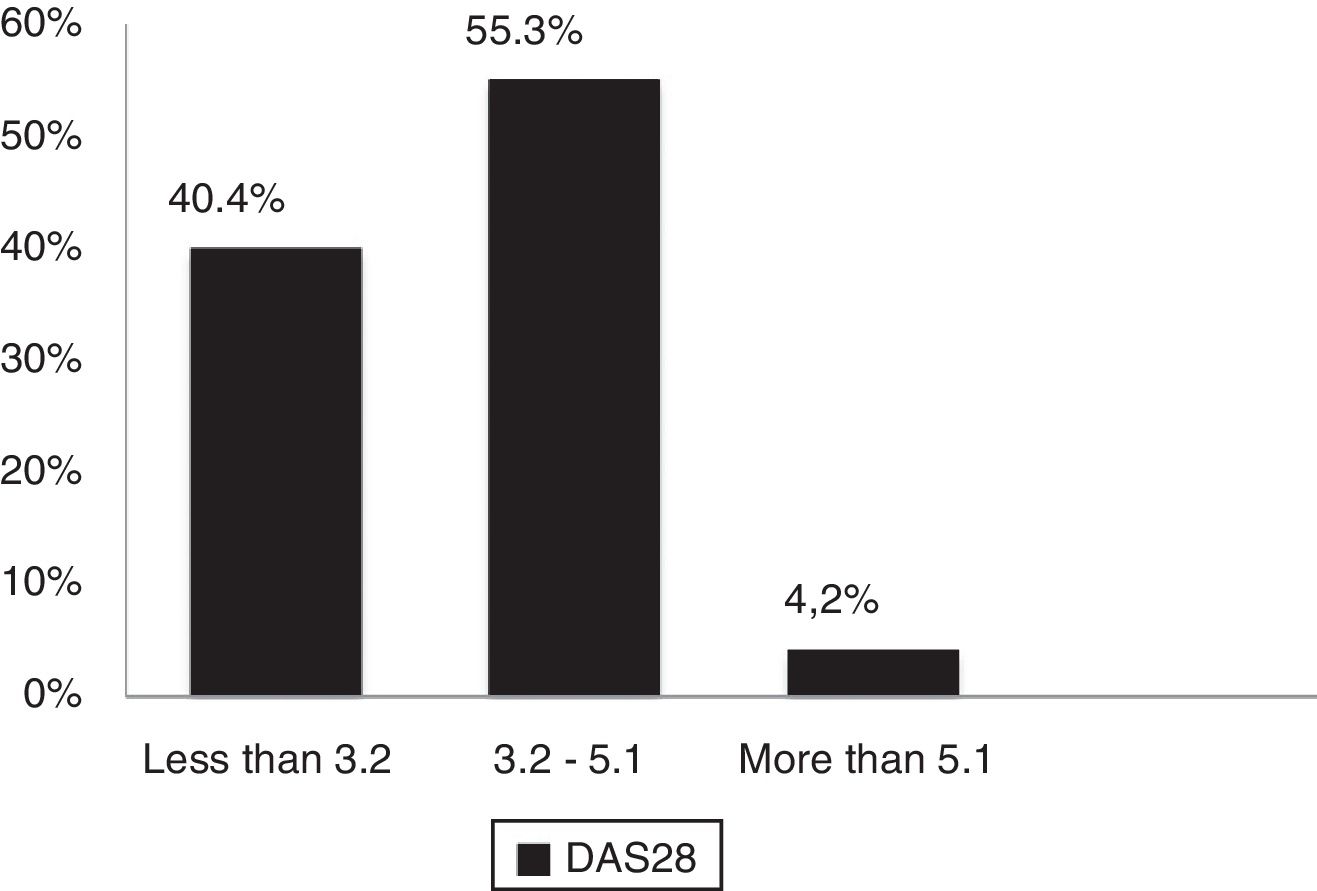

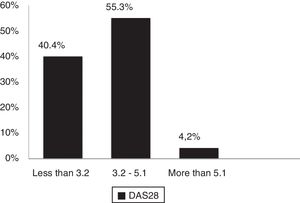

ResultsThe mean age of the 94 patients was 57 years; 76% were women, and 100% came from low socioeconomic groups. Typically, the joint disease was symmetrical, with joint swelling present in 30% of the cases, mostly involving the small and large joints of the upper limbs. Rheumatoid factor was positive in 1.06% and anti-citrulline antibodies in 0%. There were detectable levels of IL6 in 64.9%, and IL 17 in 7.45% of the patients. The severity of disease activity was determined using the DAS28 score, identifying 55.3% with moderate activity, 40.4% with mild activity, and 4.2% with high activity. The HAQ-DI identified a moderate functional limitation in 45.7% of the cases, with a mean score of 1.02. The quality of life measured with the SF-36 scale showed that all of the domains evaluated were affected but pain and the physical and emotional domains were significantly more affected.

ConclusionsPatients with post-chikungunya chronic arthritis, presented in most cases arthralgia, arthritis, functional impairment, and poor quality of life. It is then necessary to adopt comprehensive therapeutic measures for a sound intervention of this pathology.

La artropatía por virus de chikungunya (CHIKV) es una complicación frecuente secundaria a la infección inicial por este virus con un alto riesgo de progresión a secuelas funcionales y de calidad de vida.

ObjetivoIdentificar las características clínicas, inmunológicas, de discapacidad funcional y de deterioro de la calidad de vida en una muestra de pacientes colombianos con artropatía crónica por CHIKV.

MétodosSe evaluó un grupo de 94 pacientes en una ciudad colombiana durante la epidemia por CHIKV en el periodo 2014–2015.

ResultadosEn los 94 pacientes la edad media fue de 57 años, siendo el 76% mujeres y el 100% de la población afectada perteneció a estratos socioeconómicos bajos. El cuadro articular característicamente fue simétrico con inflamación articular en el 30%, mayor compromiso de articulaciones grandes y pequeñas de miembros superiores. Se identificó positividad para factor reumatoide en el 1,06%, anticuerpos anticitrulina en el 0%, niveles detectables de IL6 en el 64.9% y de IL 17 en el 7,45% de los pacientes. La severidad de la actividad articular se exploró con la escala DAS28 identificando un 55.3% con actividad moderada, 40.4% actividad leve y 4.2% con actividad alta. El HAQ-DI identificó un compromiso funcional moderado en el 45.7%, con puntaje medio de 1,02. La calidad de vida medida con la escala SF-36 mostró que todos los dominios evaluados fueron afectados con mayor compromiso de los dominios dolor, rol físico y rol emocional.

ConclusionesEn los pacientes afectados por artropatía crónica por virus chikungunya se observó artralgias, artritis, deterioro funcional y de la calidad de vida en la mayoría de la población estudiada, por lo que es necesario adoptar medidas terapéuticas en todos estos niveles para una intervención adecuada en esta patología.

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection causes a short period of acute fever with widespread rash, with limited impact on mortality but with significant short and medium term sequelae in most of the individuals affected with joint involvement.1

According to PAHO, there were 351.334 suspicious cases reported in 2016 and 152.769 confirmed cases, with a global incidence rate of 50.51 case per every 1.000 inhabitants and 172 deaths throughout the Americas.2 Some of the complications of the infection include chronic CHIKV arthropathy defined as the persistence of arthritis or arthralgia for more than 3 months, in a patient with clinical or laboratory confirmed infection.3,4 Chronic CHIKV arthropathy is frequently reported in the various series worldwide, with reports of up to 78% after 2 years of the acute infection episode.5–7 This joint involvement affects people of any age; however, the prognosis tends to be worse in the elderly, leading to a negative impact on quality of life, on functionality, and at the psychological level as measured with generic scales such as the 36-item Short -Form Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36) and the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12).7

Another aspect of the disease which is still being studied is the immune profile, since certain molecules that are predictors of chronicity have been identified, such as high TNF-α titers, interleukin (IL)-8, IL-6, and IL-12,8–10 in the acute phase, and in the chronic phase the persistence of elevated IL-6, IL-17, IL-1B, IL-8 levels, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1,10–12 suggesting interaction pathways between the initial innate immune response and the subsequent adaptative Th17 pathway as mediators of chronicity. All of these processes associated with the risk of causing erosion suggest the possibility of measuring the rheumatoid factor and the anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies as potential severity biomarkers.

In Colombia, the epidemics peak was identified between 2014 and 2015, reporting 19,566 accumulated cases by the end of13 and 1,110 cases on epidemiological week 50 in 2017,14 indicating a large volume of the population at risk of developing CHIKV arthropathy and its functional sequelae. It is important to describe the clinical characteristics of the disease in our population and to identify prognostic predictors in order to be able to design therapeutic guidelines not only in terms of pharmacology, but also in terms of rehabilitation and social support. The objective of our study was to describe the clinical characteristics, the presence of rheumatoid factor seropositivity, anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies, and the levels of IL-6 and IL-17 as potential markers for chronicity. The functional disability and the impact on quality of life were also measured using generic scales in a sample of Colombian patients with CHIKV-related chronic arthropathy.

Materials and methodsThis is and observational, cross-sectional trial with a population sample from San Juan de Nepomuceno City and municipal capital in Bolívar (Colombia), during the months of June and July, 2015. The inclusion criteria were 18 years or older, consistent with the definition of clinically suspicious or confirmed cases for CHIKV infection and the presence of joint symptoms for more than 3 months; the exclusion criteria were a prior diagnosis or clinical suspicion of inflammatory or non-inflammatory underlaying osteoarticular disease and a suspicion or a clinical or laboratory diagnosis of infection from other arthritis-associated viruses. The sample comprised patients captured from hospital and community cases meeting the inclusion criteria and accepting to participate in the study and signing the informed consent. A venous blood sample was collected from the participants which was stored at –70°C for transportation and further biochemical analysis. After collecting the blood sample, each patient was administered the HAQ-DI, SF-36, and DAS28 scales (osteoarticular examination conducted by a rheumatology resident), based on their standardization and validation as tools for assessing the severity of functional impairment, quality of life impact, and joint activity, respectively. A survey was conducted to collect clinical and sociodemographic information. The samples were processed at a reference laboratory in Bogotá (Colombia) for the determination of C-reactive protein levels (PCR: turbidity, Spin react turbilatex, SPINREACT), rheumatoid factor (RF: turbidity, Spin react turbilatex, SPINREACT), anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (QUANTA LITE CCP3 IgG EIA, INOVA), IgG Chikungunya Virus (Human Anti-Chikungunya Virus IgG ELISA Kit, Abcam), IL-6 (Thermo Scientific™ Pierce™ Human IL-6 ELISA Kits, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and IL-17 (Thermo Scientific™ Pierce™ Human IL-17 ELISA Kits, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The protocol was submitted for approval of the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine of Universidad Nacional de Colombia. All patients signed their informed consent for admission to the trial. The trial meets the requirements for research in humans, pursuant to Resolution 8430 of 1993, of the Colombian Ministry of Health, which is consistent with the rules and standards on human research ethics of the Declaration of Helsinki in 1964.

The following definitions were considered4- •

The clinic is suspicious: patient with fever, arthralgia or acute onset arthritis and rash; symptoms that cannot be explained by other medical conditions and original from a municipality which has not been declared outbreak zone.

- •

Case confirmed based on the clinic: patient with fever, arthralgias or acute onset arthritis and rash; symptoms that cannot be explained by other medical conditions and original from a municipality which has been declared outbreak zone.

- •

Case confirmed by the laboratory: suspicious case with any of the following laboratory tests positive for CHIKV: viral isolate, PCR-TR, IgM anti-chikungunya antibodies or 4-fold increase in the titer of IgG specific antibodies for CHIKV in matched samples collected 15 days apart.

All of the information from each variable collected via the data collection forms was coded and transcribed to a database in Excel 2010 (Microsoft office for Windows 10) for subsequent export and analysis using STATA 13 (Statacorp. 1985). The information obtained was reviewed in order to correct any information errors, avoid duplications, entry errors, or outliers. Statistical tools were used to describe the quantitative variables summarizing the central tendency measurements in accordance with the statistical distribution. In the case of qualitative variables, absolute sequences and percentages were used. The data shall be presented using tables and charts.

ResultsInitially, 1850 patients were identified with a clinical presentation of acute onset fever and arthralgias, of which 102 cases were clinically confirmed as CHIKV and were associated with arthropathy of more than 3 months. The clinical information, informed consent, and blood samples were collected for analysis in 94 patients. 72 patients (76%) were females. The mean group age was 57±14.9 years, with a mean duration of symptoms of 278±87.8 days. By definition, 100% presented with symptoms extending beyond 90 days, with a minimum duration of symptoms of 91 days and a maximum of 365 days. 75.5% of the affected population came from a low socioeconomic group and 45% of the total population had no schooling whatsoever (Tables 1 and 2).

Demographic characteristics of the population with CHIKV-associated arthropathies, San Juan Nepomuceno, Bolívar, Colombia, 2015.

| Characteristics of patients | n=94 |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (±SD) | 57 (±14.99) |

| Weight (kg), mean (±SD) | 70.5 (±12.87) |

| Body mass index, mean (±SD) | 26.8 (±4.17) |

| Sex (%) | |

| Females | 76 |

| Males | 24 |

| Level of education (%) | |

| None | 45.7 |

| Elementary | 34 |

| Secondary | 14.9 |

| Undergraduate | 4.3 |

| Post-Graduate: | 1 |

| Smoking (%) | |

| Yes, active | 7.5 |

| Ex-smoker | 27.7 |

| No | 64.9 |

SD: Standard deviation.

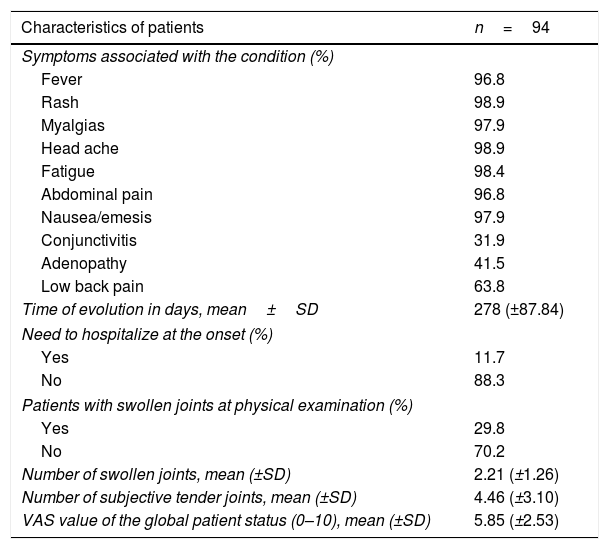

Clinical characteristics of the population with CHIKV arthropathy, San Juan Nepomuceno, Bolívar, Colombia, 2015.

| Characteristics of patients | n=94 |

|---|---|

| Symptoms associated with the condition (%) | |

| Fever | 96.8 |

| Rash | 98.9 |

| Myalgias | 97.9 |

| Head ache | 98.9 |

| Fatigue | 98.4 |

| Abdominal pain | 96.8 |

| Nausea/emesis | 97.9 |

| Conjunctivitis | 31.9 |

| Adenopathy | 41.5 |

| Low back pain | 63.8 |

| Time of evolution in days, mean±SD | 278 (±87.84) |

| Need to hospitalize at the onset (%) | |

| Yes | 11.7 |

| No | 88.3 |

| Patients with swollen joints at physical examination (%) | |

| Yes | 29.8 |

| No | 70.2 |

| Number of swollen joints, mean (±SD) | 2.21 (±1.26) |

| Number of subjective tender joints, mean (±SD) | 4.46 (±3.10) |

| VAS value of the global patient status (0–10), mean (±SD) | 5.85 (±2.53) |

SD: standard deviation.

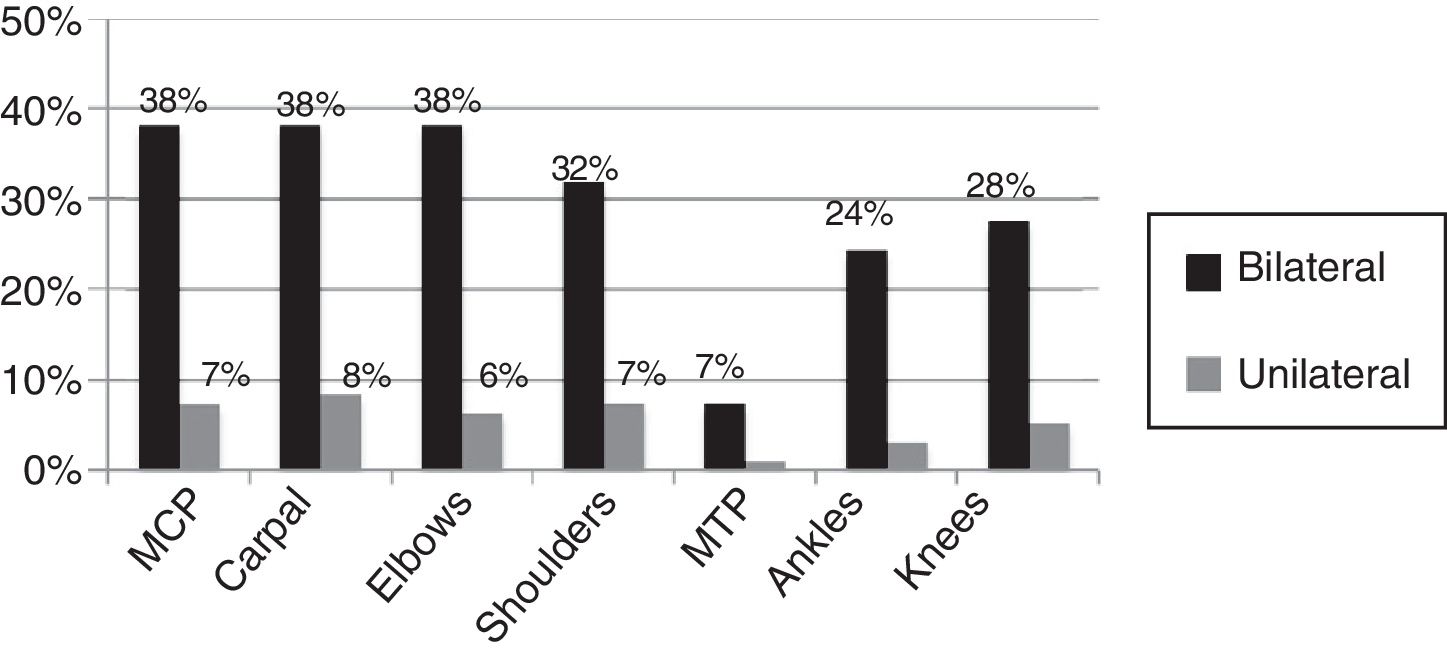

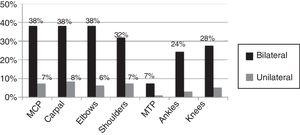

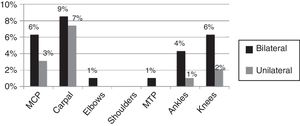

95% of the cases presented with fever, skin rash, myalgia, head ache, fatigue, abdominal pain and nausea/emesis, low back pain in 63.4% and conjunctivitis and adenopathy were identified in less than 50%. Synovitis was identified in 29.8% of the cases at the time of the assessment, with a mean of 2.21±1.26 swollen joints. The joints distribution is illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2, showing a predominantly symmetrical presentation, involving large and small joints of the upper extremities, knees and ankles.

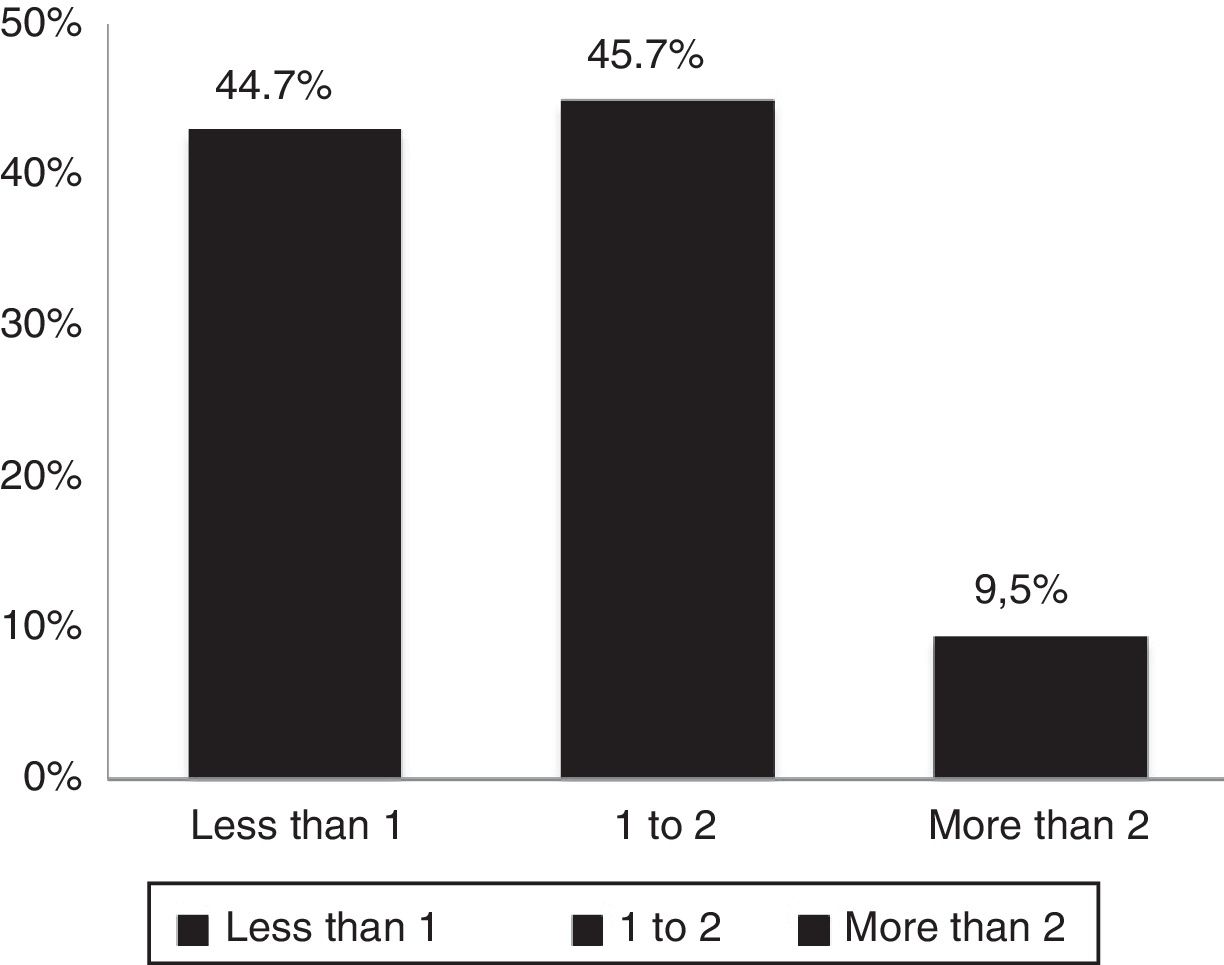

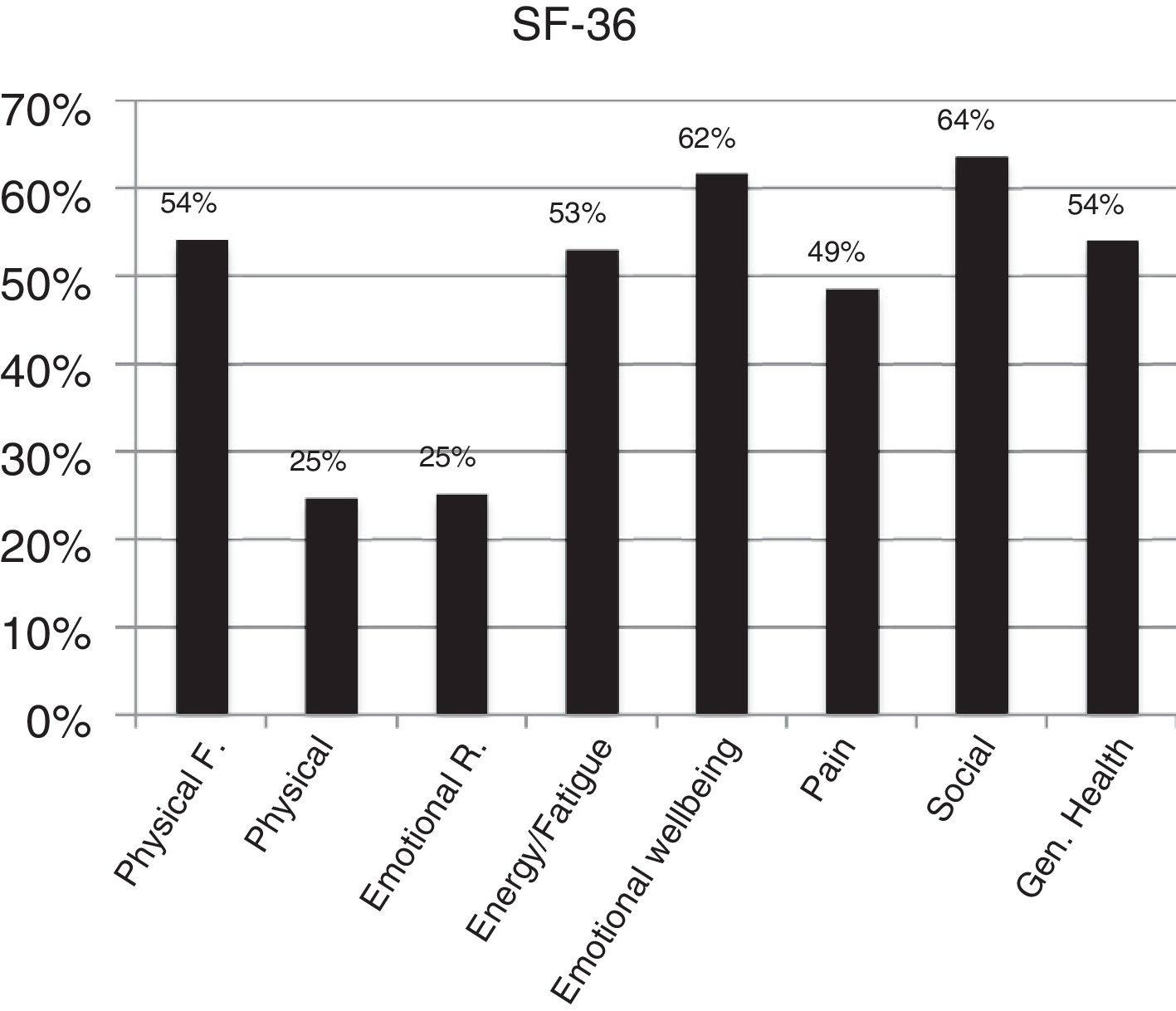

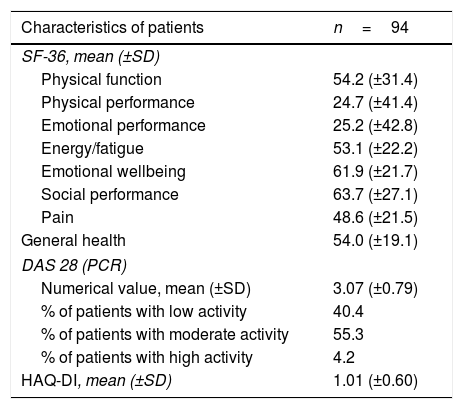

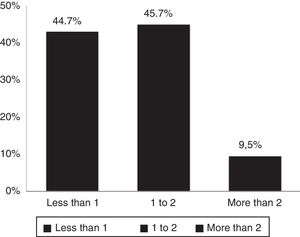

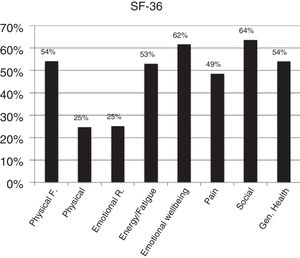

According to DAS28 activity scale, 40.4% presented with low activity (DAS28<3.2), 55.3% had moderate activity (DAS28 3.2-≥ 5.1), and only 4.2% (4 patients) had a high activity (DAS28>5.1). According to the HAQ-DI functional scale, 44.7% had mild involvement (score less than 1), 45.7% moderate (score between 1 and <2), and 9.5% severe (score of 2 or more). The generic SF-36 quality of life scale showed more involvement of the physical, emotional and pain components (percentages below 50%); however, all the domains of this test were affected and none scored above 65% (Table 3 and Figs. 3–5).

Activity Scales (DAS28), Functional (HAQ-DI) and quality of life (SF-36), San Juan Nepomuceno, Bolívar, Colombia, 2015.

| Characteristics of patients | n=94 |

|---|---|

| SF-36, mean (±SD) | |

| Physical function | 54.2 (±31.4) |

| Physical performance | 24.7 (±41.4) |

| Emotional performance | 25.2 (±42.8) |

| Energy/fatigue | 53.1 (±22.2) |

| Emotional wellbeing | 61.9 (±21.7) |

| Social performance | 63.7 (±27.1) |

| Pain | 48.6 (±21.5) |

| General health | 54.0 (±19.1) |

| DAS 28 (PCR) | |

| Numerical value, mean (±SD) | 3.07 (±0.79) |

| % of patients with low activity | 40.4 |

| % of patients with moderate activity | 55.3 |

| % of patients with high activity | 4.2 |

| HAQ-DI, mean (±SD) | 1.01 (±0.60) |

SD: Standard deviation.

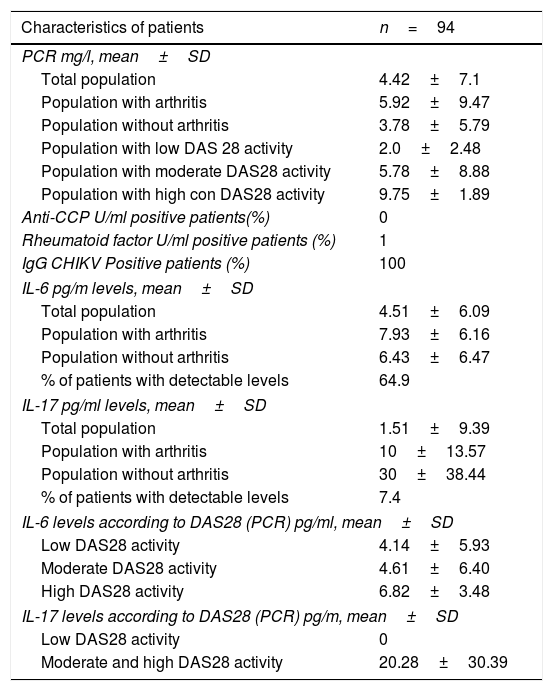

Immunologically, 100% of the participants had detectable IgG levels for CHIKV. RF positivity was identified in one patient (1.06%) and none of them were anti-CCP positive. The mean PCR levels were 4.42±7.10mg/l. Of the total number of patients, 64.9% presented detectable IL-6 levels, with a mean value of 4.51±6.09pg/ml in the total population and 7.45% of the total population had detectable IL-17 levels, with a mean value of 1.51±9.39pg/ml. In the group of patients with arthritis, the IL-6 levels were 7.93±6.16pg/ml and in the group with no evidence of arthritis, the IL-6 levels were 6.43±6.47pg/ml. The mean IL-17 levels in the arthritis group were 10±13.57pg/ml and in the non-arthritis group was 30±38.44pg/ml. In the discrimination of IL-6 values according to the degree of activity of the disease staged using DAS28, in the mild range of activity (<3.2) a mean IL-6 value of 4.14±5.93pg/ml was identified; in the moderate range value (3.2–5.1) the mean IL-6 was 4.61±6.40pg/ml, and in the high activity (>5.1) was 6.82±3.48pg/ml. In the case of IL-17, since 7 patients showed detectable levels (6 of them in the moderate activity group, one in the high activity group and none in the mild activity group), the moderate and high activity groups were analyzed together, resulting in mean IL-17 values of 20.28±30.39pg/ml (Tables 3 and 4).

Immune characteristics of the population with CHIKV arthropathy, San Juan Nepomuceno, Bolívar, Colombia 2015.

| Characteristics of patients | n=94 |

|---|---|

| PCR mg/l, mean±SD | |

| Total population | 4.42±7.1 |

| Population with arthritis | 5.92±9.47 |

| Population without arthritis | 3.78±5.79 |

| Population with low DAS 28 activity | 2.0±2.48 |

| Population with moderate DAS28 activity | 5.78±8.88 |

| Population with high con DAS28 activity | 9.75±1.89 |

| Anti-CCP U/ml positive patients(%) | 0 |

| Rheumatoid factor U/ml positive patients (%) | 1 |

| IgG CHIKV Positive patients (%) | 100 |

| IL-6 pg/m levels, mean±SD | |

| Total population | 4.51±6.09 |

| Population with arthritis | 7.93±6.16 |

| Population without arthritis | 6.43±6.47 |

| % of patients with detectable levels | 64.9 |

| IL-17 pg/ml levels, mean±SD | |

| Total population | 1.51±9.39 |

| Population with arthritis | 10±13.57 |

| Population without arthritis | 30±38.44 |

| % of patients with detectable levels | 7.4 |

| IL-6 levels according to DAS28 (PCR) pg/ml, mean±SD | |

| Low DAS28 activity | 4.14±5.93 |

| Moderate DAS28 activity | 4.61±6.40 |

| High DAS28 activity | 6.82±3.48 |

| IL-17 levels according to DAS28 (PCR) pg/m, mean±SD | |

| Low DAS28 activity | 0 |

| Moderate and high DAS28 activity | 20.28±30.39 |

SD: Standard deviation.

The variability in clinical behavior of patients that develop chronic joint manifestations due to CHIKV is remarkable; some studies such as Chopra et al.15 in India in 2012, reported just 4% of persistence of symptoms after one year; however, others report up to 60–75%, in accordance with French cohorts in Reunion island in 2013.16,17 Hence there is a significant heterogeneity in joint involvement based on geography and probably the phenotype of the disease. The design of this study did not allow for any conclusions with regards to the rate of persistence of joint symptoms; however, it does identify some clinical characteristics of CHIKV-associated arthropathy in the Latin population. In our setting, the clinical symptoms persisted for around 9 months following the acute presentation; approximately 2/3 of the population are females, consistent with the reports from other authors,5,16,18,19 suggesting some type of susceptibility in women. The population identified was mostly from low socioeconomic sectors, the majority with little or no schooling, which possibly reflects some selection bias. However, we should not rule out the fact that this population may have a higher risk of developing the disease because of poor knowledge about management of drinking water storage, due to the association between this variable and the vector replication.14

It should be highlighted that the predominant joint involvement was symmetrical with synovitis – around 30% of the cases – similar to the findings reported in other case series that also report between 20 and 65% of synovitis,5,20,21 and the presence of inflammatory type of pain, regardless of the presence of joint inflammation in up to 70% of the patients affected.6 The international literature reports variable frequencies of RF and anti-CCP positivity, reporting between 12 and 43% of RF positivity in India,22 and between 30 and 50% for RF/anti-CCP according to French series,19,23 probably indicating a more severe clinical profile in some of these groups, and with a higher risk of erosion. Prior studies in the Colombian population report 4.2%24 seropositivity for these antibodies, which is similar to the findings by Manimunda et al.20 also in India and Schilte et al.17 in France; this may be a reflection of different selection criteria in the various trials. Some may have selected a population with more severe inflammatory involvement or patients with pre-existing undiagnosed inflammatory arthropathy.

The consistency of the seropositivity data in our population may reflect a less aggressive phenotype with less risk of progression to erosive disease in the long term. Further longitudinal and follow-up studies are needed to clarify this hypothesis. Similarly, the identification of a low prevalence of IL-17 elevation supports the idea of a less severe clinical profile and possibly an improved prognosis in the long term, or the likely selection of patients in a relatively early stage (the first year of the disease) in which the Th17 line differentiation is not yet identifiable, as is the case in other types of inflammatory arthritis.

In terms of the cytokines profile, the percentage of patients with detectable IL-6 was significant in our population - 65%-, similar to the data reported by Jaller et al.24 also in the Colombian population, with 95% positivity for this marker. Moreover, the IL-17 levels in our studies were only detectable in 7.4%. This highlights the significant role of IL-6 in the pathophysiological mechanism for the joint inflammatory process, without ruling out other systemic effects. One of the limitations in our study was the cross-sectional assessment of patients, which limited the possibility to do a long term evaluation of the cytokines profile and their evolution over time.

CHIKV-associated arthropathy has shown a significant impact on the functional, emotional and quality of life aspects of the different populations affected,7,19,20 with an estimated economic impact in the Reunion island of 34 million Euros per year, between 2005 and 2006.17 Our population evidenced the same pattern reported with significant compromise of health-related quality of life, mainly in terms of pain, physical and emotional performance, but in general of all the aspects assessed with the SF-36 scale. In terms of the functional capacity assessment, the generic HAQ-DI25 identified in our population a moderate functional involvement, in around fifty percent of the population and a severe compromise defined as an HAQ-DI score between 2 and 3 in almost 10% of the patients. This indicates that the level of functional limitation in this population, most of them in working age, generated a significant impact from the labor and social point of view. Since there are no long term studies that clearly typify the evolution over time, one may suspect that the functional and quality of life compromise in these patients could be affected, and so it is necessary to conduct long term prospective trials assessing the impact of the disease the labor, social and psychological realms.

The limitations of our study were its cross-sectional nature that prevented follow-up over time to conduct prospective assessments of erosion risk markers (RF and anti-CCP) and the fact that our population exhibited a relatively early clinical evolution as compared to other studies involving patients with 1 and 3 years of evolution of symptoms.

In conclusion, our study evidenced the significant functional and quality of life involvement of the affected patients, with almost one third presenting with arthritis in the first 9 months following the acute infection and more than 60% with detectable IL-6 levels as a potential immune marker for chronicity, but with a low seropositivity for rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP. Further prospective studies are required to follow-up these populations in order to monitor their clinical and functional behavior, as well as the serum markers for severity. Due to the significant quality of life impact, it is important to adopt therapeutic measures with medications and social and functional interventions.

FinancingThis paper was funded by:

- 1

The Colombian Association of Rheumatology through Public Announcement in 2016.

- 2

National Announcement of Projects for strengthening of Research, Development and Innovation of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia 2016–2018, code Hermes 35925, Code Quipu: 202010026761.

No conflicts of interest to disclose

Dr. Carlos Saavedra, internist, infectious disease specialist, clinical epidemiology MSc. Department of Internal Medicine. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Please cite this article as: Abella J, et al. Caracterización clínica e inmunológica de la artropatía crónica por virus chikungunya y su relación con discapacidad funcional y afectación de la calidad de vida en una cohorte de pacientes colombianos. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2019;26:255–261.