Conversion disorder is a challenge for clinicians due to the conceptual gaps as regards its pathogenesis, the way in which it converges with other psychiatric disorders, and the lack of approaches to the experiences of both patients and family members with the disease.

ObjectiveTo describe Explanatory Models (EM) offered to caregivers of paediatric patients with conversion disorder who attended the Hospital de la Misericordia.

MethodsA qualitative study was conducted with a convenience sample of 10 patients who attended the Hospital de La Misericordia, ¿Bogota? between May 2014 and April 2015. The tool used was an in-depth interview applied to parents and/or caregivers.

ResultsCaregivers have different beliefs about the origin of the symptoms, especially considering sickness, magical–mystical factors, and psychosocial factors. The symptoms are explained in each case in various ways and there is no direct relationship between these beliefs, the pattern of symptoms, and help-seeking behaviours. Symptomatic presentation is polymorphous and mainly interferes in the patient's school activities. The medical care is perceived as relevant, and psychiatric care as insufficient. Among the therapeutic routes, consultations with various agents are described, including medical care, alternative medicine, and magical–religious approaches.

ConclusionsEMs in conversion disorder are varied, but often include magical–religious elements and psychosocial factors. The underlying beliefs are not directly related to help-seeking behaviours or other variables.

El trastorno conversivo es un reto para los clínicos por los vacíos conceptuales en lo que respecta a la patogenia y cómo confluyen otras entidades psiquiátricas y la falta de aproximaciones a las vivencias tanto de pacientes como de familiares con la enfermedad.

ObjetivoDescribir los modelos explicativos (ME) que utilizan los cuidadores de niños y adolescentes con trastorno conversivo que consultan al Hospital Pediátrico de La Misericordia.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio cualitativo con una muestra por conveniencia de 10 casos atendidos entre mayo de 2014 y abril de 2015. La herramienta usada fue una entrevista en profundidad con padres y/o cuidadores.

ResultadosLos cuidadores tienen diversas creencias en torno al origen de los síntomas, y consideran principalmente enfermedad, factores mágico místicos y factores psicosociales. Se explican los síntomas en cada caso de varias maneras, y no se encontró una relación directa entre estas creencias, el patrón de síntomas y los comportamientos de búsqueda de ayuda. La presentación sintomática es polimorfa y genera interferencia principalmente en la actividad escolar de los pacientes. La atención médica se percibe como pertinente y la atención psiquiátrica, como insuficiente. Entre los itinerarios terapéuticos, se describen consultas con diversos agentes, además de la atención médica, incluidas medicinas alternativas y enfoques mágico-religiosos.

ConclusionesLos ME en trastorno conversivo son variados, pero incluyen con frecuencia elementos mágico-religiosos y factores psicosociales. Las creencias subyacentes no se relacionan directamente con la búsqueda de ayuda u otras variables.

Somatic symptom disorders are characterised by physical signs or symptoms which suggest a “medical” disease, but when investigated, no condition can be found to fully explain them.1 When the symptoms are suggestive of a neurological condition, they are referred to as conversion disorders.2 Even though this type of disorder has a long trajectory in the history of humanity, it can be extremely challenging in medical practice, partly due to conceptual gaps, particularly in the pathogenesis or psychopathology, and also because of the lack of concrete answers doctors are able to provide and the suffering it causes to patients and their families.

There have been a number of different explanations for this group of disorders over the course of history, depending on the theory with the highest degree of consensus at the time.3 However, in these endeavours there has been little consideration of how the sufferer and those around them experience the disease, and this creates barriers for healthcare workers, limiting their understanding of and response to the particular problems of those affected.4 The experience of illness and suffering transcends the mere individual experience of one symptom or another and becomes an experience that shakes up different aspects of the subject's life, beyond their body and even their individuality, and affects all those around them. Suffering then moves to an interpersonal, relational level, heavily mediated by cultural representations of health and disease. Within the initiatives emerging to better understand this subject area, we find ourselves in the social sciences, and specifically in the concept known as explanatory models (EM) developed by Kleinman,5 which refers to: “... the notions about an episode of sickness and its treatment that are employed by all those engaged in the clinical process”.

Patients, relatives and/or caregivers explain health problems in different ways: this includes explanations about the origin of symptoms, their causes and how they progress. It is also closely related to help-seeking behaviours and expectations of treatments. These models are influenced by sociocultural factors such as the country or region of origin, the religious belief system and life experience. Having a good knowledge of these models in psychiatric practice gives us a better understanding of the subjective experience of the disease, attitudes towards care, expectations of care and practical aspects related to the treatment plans. EMs also provide valuable information to guide psychoeducational programmes for both family members and patients. They help us form closer relationships with patients, leading to greater satisfaction with care, better adherence to treatment6 and lower re-admission rates, which should ultimately improve the clinical prognosis.7

This article describes the EMs reported by the caregivers of children with conversion disorder treated by the Department of Psychiatry of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia [National University of Colombia] in a paediatric hospital in the city of Bogotá. Research of this type has been carried out in adult psychiatry on disorders such as schizophrenia,8,9 bipolar disorder10–12 and depression,13,14 and in child psychiatry, on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD),15–17 depression,13,14 autismo,18 obsessive-compulsive disorder19 and, more generally, on groups of indiscriminate disorders, seeking to determine the relationship with other variables such as race and ethnicity.20 There are also studies in other areas of medicine such as clinical oncology21 and orthopaedics.22 However, to the extent that we reviewed the literature, we found no studies of this type in the paediatric population with conversion disorder.

MethodsThis was a qualitative study, with a grounded theory and phenomenology design, in which a semi-structured interview was applied to parents and/or caregivers. All the interviews were conducted by the principal investigator. Patients were not included as, depending on their age and stage of cognitive development, their responses would not necessarily vary due to individuality, it would be difficult to evaluate all the topics in all cases (at least in the same way) and, consequently, there would be difficulties in comparing all the narratives. All this would affect credibility, a key aspect for the methodological rigour of qualitative studies. Moreover, we preferred interviews with parents over other caregivers, as it is usually the parents who are in charge of the upbringing, care and custody of the children. The approach using a semi-structured interview allowed for a more open and flexible investigation than with structured interviews, and avoided the logistical difficulties inherent in focus group interviews.23

We took 10 cases diagnosed with conversion disorder by a child psychiatrist, by non-random, intentional and non-probabilistic sampling of patients and their respective families in the outpatient clinic and/or admissions unit of the Fundación Hospital Pediátrico de La Misericordia. In all cases there was also a thorough assessment by paediatric neurology and by other specialist areas, according to the particular features of each case and as part of the study to rule out somatic diseases.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe inclusion criteria were to be a parent and/or caregiver of a child or adolescent aged from six to 17 years diagnosed with conversion disorder by a child psychiatrist according to DSM-5 criteria. The exclusion criteria were being a parent and/or caregiver of a child or adolescent with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures diagnosed by a paediatric neurologist, refusing to participate in the study or not to agreeing to audio recording of the interview.

Data collection procedureWe first reviewed the medical records to verify diagnoses, ages and eligibility for the study, and to verify the concepts issued by child psychiatry certifying the diagnosis of conversion disorder and paediatric neurology, ruling out psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Next, we explained the nature of the research, the methodology, the expected benefits and risks, and the measures taken to minimise those risks, to the parents/caregivers. Lastly, we resolved any queries they had. They were given sufficient time to read the whole study information document. Then, if they agreed, the informed consent form was signed and they were given a copy of it. Subsequently, we entered the identification data (medical record number) into a master table, to which only the principal investigator, in charge of carrying out the interviews, had access. Certain demographic data were also collected and recorded in the case report form. A serial number from 1 to 10 was assigned to each case, according to the order in which the interviews were conducted, which was used to identify that case on the consent forms, in the master table, on the case report form and at the beginning of each audio recording. The interview, lasting approximately 60min, was carried out with the caregivers responsible for the patient in the outpatient department offices or rooms in the different hospital admission areas at Hospital de la Misericordia. This interview was recorded in digital format for later transcription and analysis.

The following subjects were discussed in the interviews:

- 1.

Beliefs about the aetiology of the disorder and how they related to help-seeking behaviours, and the information provided by the medical staff looking after them.

- 2.

The chronological order in which the symptoms appeared, and a phenomenological description of them.

- 3.

The impact of the symptoms on both the patient and family life.

- 4.

Treatments sought, their opinion of them and their specific opinion of the medical and psychiatric treatments.

- 5.

The way the family group reacts to a hypothetical situation of illness of one of its members.

In the interviews, we tried not to identify patients by name and tried not to go into detail about emotionally sensitive aspects not relevant to this research.

Information analysisA number of variables were taken into account (age, gender, origin, socioeconomic stratum and household members), for which a descriptive analysis was carried out together with their measures of dispersion in continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. The analyses were carried out with the statistical program R, version 3.2.0 for Mac, using the graphical user interface R commander.

For the qualitative analysis, the interviews were transcribed by an anthropologist with experience in qualitative research methods. For the purposes of protecting confidentiality, words that might have identified the patient and/or their relatives were omitted and each case was identified with the label “Conversion disorder n”, where n was the assigned serial number.

Initially, an inductive thematic analysis was carried out by the principal investigator, with the collaboration of a psychiatrist not involved in the study who was training to be a child and adolescent psychiatrist. Both read the transcripts, in order to fully understand the content and outline a plan of analysis that included the topics discussed. Separately, the principal investigator and the psychiatrist pre-coded the transcripts, then discussed the precoding together to arrive at a definitive coding scheme. They then re-read the transcripts applying the new scheme and using the agreed categories to identify all the possible explanations given to the origin of the symptoms, the different lines of treatment, the consequences perceived by both relatives and patient in the context of the chronological order the symptoms developed, and perceptions of the medical/psychiatric care. Last of all, they looked for any emerging themes. Categorisations were not proposed in advance in order to avoid bias in the conducting of interviews and/or in the analysis as such. However, it was sometimes necessary to propose certain themes in the interviews in order to obtain more extensive information.

To facilitate the processing of the working material, the manipulation of the codes within the transcriptions and to assess aspects such as the frequency of appointments and the relationship between the different categories, we used the qualitative data analysis software Atlas.ti version 1.0.24 (94) for Mac.

After that, the narratives were analysed based on the previous coding. The narratives implicitly contain codes for different cultural representations. For the purposes of this study and based solely on the ethnographic evidence, the representations were addressed in terms of the concept of health and sickness and the perceived causes of symptoms, and described, analysed and used as a point of correlation with help-seeking behaviour, perceptions about medical and psychiatric care and the impact on daily life. This was done from the perspective of the caregivers.

Ethical considerationsWe followed the “Scientific, Technical and Administrative Standards for Health Research” set out in Colombian Ministry of Health Resolution No. 8430 of 1993.24 For the preparation of the informed consent form, we followed the parameters of Article 15 of the same Resolution. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Universidad El Bosque, the university where one of the investigators was completing his specialisation studies in child and adolescent psychiatry.

ResultsGeneral information about the sampleTen interviews were carried out, nine mothers and one father. Nine families were from Bogotá and one patient came from the town of Simijaca (Cundinamarca). According to Colombia's social stratification system, socioeconomic stratum 2 was predominant (n=7), one family lived in stratum 1, one family in 3 and another was unaware of this categorisation. The patients were aged from 9 to 17 years, with a median of 13.5 years.

Distribution by gender was equal: five females and five males. The study had an equal gender distribution, which should be understood in the context of a sample chosen for convenience and not at random, although without making it any less representative. With regard to household members, six lived with both parents and four lived with their mother only. Nine lived with their siblings. In one case, apart from the primary family group, the patient lived with additional family members and in one other case, the patient lived with people who were not relatives.

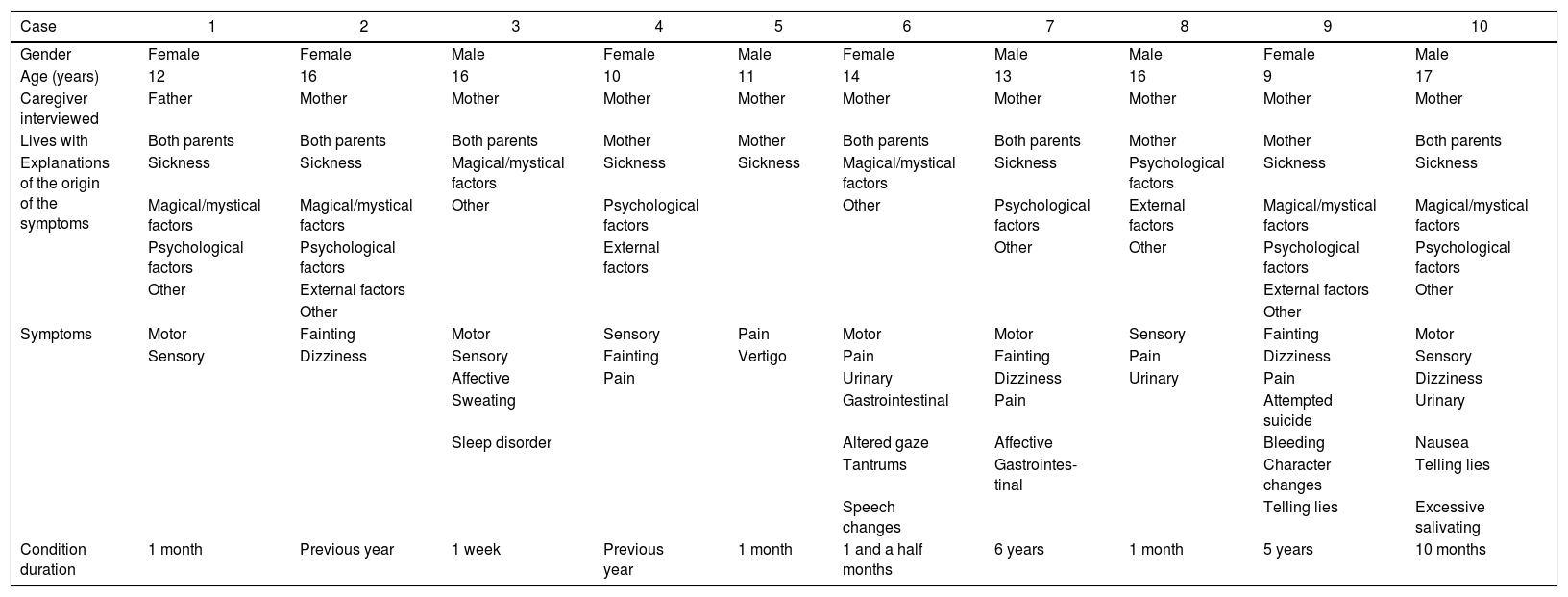

Beliefs about the origin of the symptomsThe caregivers had different beliefs about the origin of the symptoms. Table 1Table 1 shows a summary of the explanations given in each of the interviews related to the demographic data, the reported symptoms and the duration of the condition.

Explanations of the origin of the disease.

| Case | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Male | Female | Male |

| Age (years) | 12 | 16 | 16 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 16 | 9 | 17 |

| Caregiver interviewed | Father | Mother | Mother | Mother | Mother | Mother | Mother | Mother | Mother | Mother |

| Lives with | Both parents | Both parents | Both parents | Mother | Mother | Both parents | Both parents | Mother | Mother | Both parents |

| Explanations of the origin of the symptoms | Sickness | Sickness | Magical/mystical factors | Sickness | Sickness | Magical/mystical factors | Sickness | Psychological factors | Sickness | Sickness |

| Magical/mystical factors | Magical/mystical factors | Other | Psychological factors | Other | Psychological factors | External factors | Magical/mystical factors | Magical/mystical factors | ||

| Psychological factors | Psychological factors | External factors | Other | Other | Psychological factors | Psychological factors | ||||

| Other | External factors | External factors | Other | |||||||

| Other | Other | |||||||||

| Symptoms | Motor | Fainting | Motor | Sensory | Pain | Motor | Motor | Sensory | Fainting | Motor |

| Sensory | Dizziness | Sensory | Fainting | Vertigo | Pain | Fainting | Pain | Dizziness | Sensory | |

| Affective | Pain | Urinary | Dizziness | Urinary | Pain | Dizziness | ||||

| Sweating | Gastrointestinal | Pain | Attempted suicide | Urinary | ||||||

| Sleep disorder | Altered gaze | Affective | Bleeding | Nausea | ||||||

| Tantrums | Gastrointes- tinal | Character changes | Telling lies | |||||||

| Speech changes | Telling lies | Excessive salivating | ||||||||

| Condition duration | 1 month | Previous year | 1 week | Previous year | 1 month | 1 and a half months | 6 years | 1 month | 5 years | 10 months |

Of the 10 cases, in seven, the respondents explained the condition through various factors that we generically refer to as “psychological” (including themes such as “manipulation”, “nerves”, “mental illness”, “attention-seeking”); also in seven cases, they explained it as something which could be called “sickness” (in some cases with details such as “effects of anaesthesia”, effect of “falling”, “lowering of defences”); six respondents included magical/mystical factors among the explanations for the symptoms, such as “witchcraft”, spells by third parties, possession by spirits or “test of God”; four explained them as a consequence of external factors such as sexual abuse, separation of parents, “a lot of work” or moving house. Other ways of explaining the symptoms included that it was not an illness (n=3), unknown origin (n=3), effects of drugs (n=1), hereditary (n=1) and due to “not eating” (n=1). There was no specific pattern of explanations according to the gender or age of the patient (Table 2).

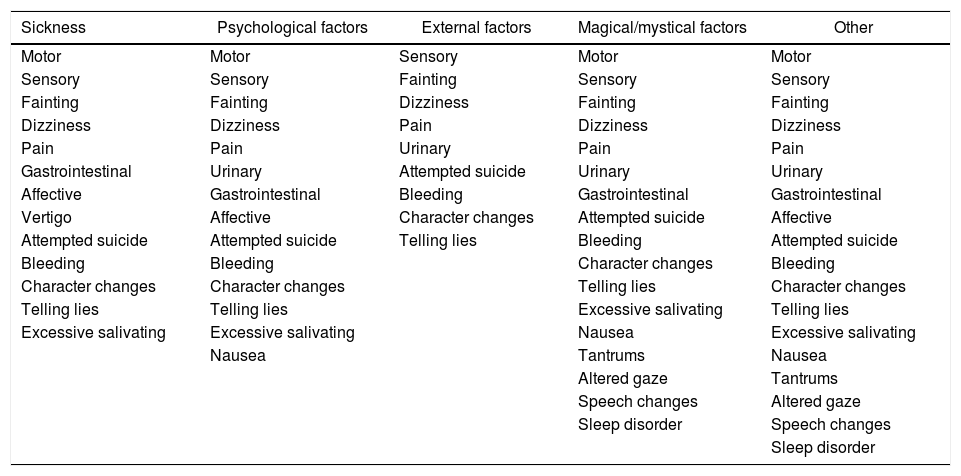

Symptoms according to the origin of the disorder.

| Sickness | Psychological factors | External factors | Magical/mystical factors | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor | Motor | Sensory | Motor | Motor |

| Sensory | Sensory | Fainting | Sensory | Sensory |

| Fainting | Fainting | Dizziness | Fainting | Fainting |

| Dizziness | Dizziness | Pain | Dizziness | Dizziness |

| Pain | Pain | Urinary | Pain | Pain |

| Gastrointestinal | Urinary | Attempted suicide | Urinary | Urinary |

| Affective | Gastrointestinal | Bleeding | Gastrointestinal | Gastrointestinal |

| Vertigo | Affective | Character changes | Attempted suicide | Affective |

| Attempted suicide | Attempted suicide | Telling lies | Bleeding | Attempted suicide |

| Bleeding | Bleeding | Character changes | Bleeding | |

| Character changes | Character changes | Telling lies | Character changes | |

| Telling lies | Telling lies | Excessive salivating | Telling lies | |

| Excessive salivating | Excessive salivating | Nausea | Excessive salivating | |

| Nausea | Tantrums | Nausea | ||

| Altered gaze | Tantrums | |||

| Speech changes | Altered gaze | |||

| Sleep disorder | Speech changes | |||

| Sleep disorder |

In most cases there was a combination of several EMs for the conversion disorder. However, in one case there was one single EM and in two cases there were two. In the other cases (n=7), the respondents had three, four or five EMs for the symptoms. This was also not affected by the age or gender of the patient, but it was influenced by the time since onset; the longer the patient had been having the symptoms, the greater the number of explanations, as exemplified in patients 1, 5 and 3. We found that attributing external factors was always accompanied by behavioural problems.

In most cases, it was perceived that the central nervous system was affected (n=4), although other organs or systems were also mentioned as affected, such as “the spine” (n=1), the heart (n=1), the extremities (n=2) and the kidneys (n=1).

Experience of symptomsThe duration of the condition varied greatly, from five years to one week. There was also a variety of symptoms; the most common being pain (n=6), followed by motor (n=5) and sensory symptoms (n=5), fainting (n=4) and dizziness (n=4). In five cases, symptoms were found that could clearly be classified as psychiatric, such as attempted suicide (n=1), tantrums (n=1), affective changes (n=2), changes in character (n=1) and lying (n=2). In five cases, in addition to the neurological and psychiatric symptoms, they also reported symptoms affecting other systems, such as urinary (n=3), gastrointestinal (n=2) and even bleeding (n=1). We have to remember that motor and/or sensory symptoms are essential for the diagnosis of conversion disorder,2 although that does not exclude the presence of other symptoms in different systems.

The number of symptoms in each case varied from two to seven. One patient had seven symptoms, three patients had six, two had four, one had three and three had only two. In four cases the pattern of symptoms was described as constant and in five, episodic.

When trying to correlate the symptoms and explanations for the origin of the illness, our only significant finding was that those who attributed it to external factors had fewer symptoms, did not report motor symptoms and more often reported “fainting” (Table 2).

Impact on daily lifeIn most of the cases, the patient's difficulties were apparent in the school environment: absenteeism (n=7), poor academic performance (n=2) and dropping out (n=1); other consequences were mood changes, separation from friends, not leaving the house, not being able to do physical activity, “feeling watched” and “knowing who their real friends are”.

For the families, the changes in their daily life were vague and non-specific: upheaval was mentioned (n=1), that the patients’ “siblings take care of them in the hope of them getting better” (n=1), absence from work (n=2), more together (n=2), emotional trauma (n=2), none (n=2) or not specified (n=2). It was striking that the perception of consequences for the family had positive connotations in a significant number of the cases: in two cases, they spoke of the symptoms as a reason for bringing the family together; and in another case, the siblings had the chance to be closer to the patient. No particular relationship was found between the explanations of the origin of the symptoms and the effects on daily life.

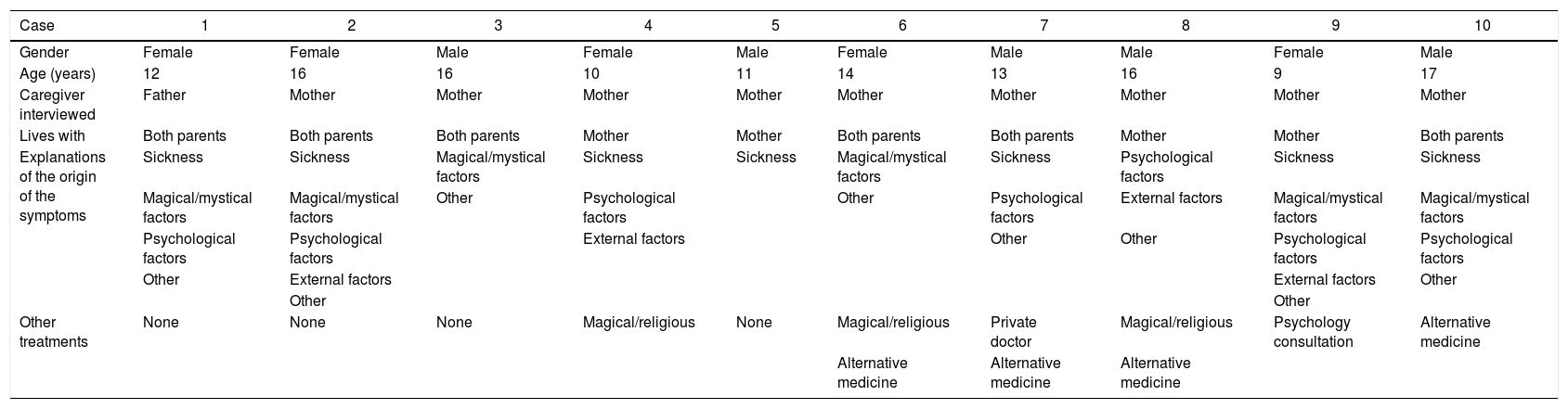

Treatment-related aspectsMost of those interviewed (seven) said they had looked for different options from medical/psychiatric care. The use of treatments with a magical/religious component was reported in three cases (included prayers, supplication, healing masses, exorcisms or consulting centres that identify with “Saint Gregory”) and alternative medicines in four cases (“natural medicine”, homoeopathy); other steps taken were consulting a private doctor (one case) and psychology consultation (one case). On comparing the above treatments with the explanations of the origin of the illness, it was striking that resorting to magical/mystical treatments was not necessarily related to explaining the symptoms as having a magical/mystical origin; as seen in patients 4 and 8 (Table 3).

Seeking help and explanations.

| Case | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Male | Female | Male |

| Age (years) | 12 | 16 | 16 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 16 | 9 | 17 |

| Caregiver interviewed | Father | Mother | Mother | Mother | Mother | Mother | Mother | Mother | Mother | Mother |

| Lives with | Both parents | Both parents | Both parents | Mother | Mother | Both parents | Both parents | Mother | Mother | Both parents |

| Explanations of the origin of the symptoms | Sickness | Sickness | Magical/mystical factors | Sickness | Sickness | Magical/mystical factors | Sickness | Psychological factors | Sickness | Sickness |

| Magical/mystical factors | Magical/mystical factors | Other | Psychological factors | Other | Psychological factors | External factors | Magical/mystical factors | Magical/mystical factors | ||

| Psychological factors | Psychological factors | External factors | Other | Other | Psychological factors | Psychological factors | ||||

| Other | External factors | External factors | Other | |||||||

| Other | Other | |||||||||

| Other treatments | None | None | None | Magical/religious | None | Magical/religious | Private doctor | Magical/religious | Psychology consultation | Alternative medicine |

| Alternative medicine | Alternative medicine | Alternative medicine |

When asked about the ideal treatment, there were different responses: continuing their studies was mentioned (n=1); “that it should be in one single place” (n=1); exorcism (n=1); psychology-based therapies (n=1); therapies (n=1); or simply didn’t know (n=2).

Eight of the interviewees were satisfied with the medical care received; only two mentioned uncertainty about or disagreement with the care or deficient care. However, there was a negative perception in general of the psychological and/or psychiatric care received, expressed in terms of disagreement (n=2), insufficient-“they need to talk” (n=2), inappropriate (n=1), poor relationship with the staff (n=1) or temporary improvement (n=1). Only three cases were satisfied with the care.

We thought it would be useful to know what the families tended to do for ailments. In three cases contacting medical staff was the first option, the others “consulted the pharmacist” (n=3), made “homemade” remedies (n=3) or simply “put up with it” (n=2). It should be pointed out that all the population included in the study had access to the health service, otherwise they would not have been receiving care in the hospital centre where the study was conducted.

DiscussionThe main findings of the study can be summarised as follows:

- •

Caregivers of children with conversion disorder give multiple explanations for the origin of the symptoms, and the notion of a “type of illness” with nervous system involvement predominates as the cause.

- •

Psychosocial factors and magical/mystical factors are also very frequently cited and several models coexist in a single case, with the patient being perceived as a passive entity, a victim of these factors.

- •

There is no direct relationship between the different explanations for the origin of the condition and variables such as patient gender and age, symptom profile or time since onset.

- •

Nor is there a correlation between these explanations and the interference generated in everyday life.

- •

Children with conversion disorder have a large number of symptoms in addition to those that seem to be neurological.

- •

The main impact of the symptoms on the patients’ daily life as perceived by the caregivers is the effect on schooling, expressed as absenteeism, dropping out of school or poor academic performance.

- •

The effects on the daily life of the family are less clear and may have positive connotations in some cases.

- •

Caregivers very often seek other treatment options, namely alternative medicines and magical/religious approaches, but this is not necessarily related to any particular way of explaining the origin of the symptoms.

- •

In general, there is adherence to medical care, but not psychiatric care, which is perceived as insufficient.

In the clinical approach with these patients, we have to remain aware that there is no single EM and that within treatment plans, the medical or psychiatric concept is just another step in the search for answers and solutions. The EMs involve factors which are clearly cultural, such as religion and magical beliefs, although there are also intrapsychic and psychosocial factors, which should be directly and actively addressed. We have to recognise the limitations in reconstructing an experience of illness solely from the perspective of the patient (or their family, in the case of children) in the context of medical/psychiatric care, but this article aims to open up a new perspective for understanding the condition.

In the literature search by the author, no other studies were found that investigated EM in conversion disorder, either in children and adolescents or in adults, so it was not possible to compare our findings with similar studies. We also have to bear in mind that this is a subject area highly sensitive to the cultural environment and that there are very few studies which evaluate EM and include Spanish-speaking and Latin American psychiatric populations; we found only five, two in ADHD,15,16 one in depression13 and two in bipolar disorder.12,25 Only the first two included the paediatric population, while the others were conducted in adults.

All the studies report a multiplicity of ways to explain illness. In a detailed analysis of the two representative studies in the Latin American paediatric population, one of them, published in 2008,15 was found to have been carried out at this same hospital in parents of children with other conditions (ADHD) by the Universidad Nacional de Colombia Department of Psychiatry. They examined the EMs of ADHD and the treatment plans, focusing on the narratives. That study found more explanations relating to antenatal and perinatal stages, which we did not find in our study. In addition, more family interfering factors were found and, due to the characteristics of the disorder, the treatment plans were different and included consultations with psychology, occupational and language therapy, as well as school support. Magical/mystical elements were nevertheless also present, as well as an important role being given to external stressors and the concept of trauma. The other study, published in 2004 and conducted in the United States, also explored the beliefs of parents of children with ADHD, according to race and ethnicity.16 They reported that the Latin population tended to more often use the explanation of trauma and behavioural problems (grouped in that study under the category “personality”). Unlike in our study, “spiritual” causes were only mentioned by a very small proportion. It would appear then that explanations mediated by external factors and/or traumas and those attributed to behavioural problems are the same as those frequently offered by parents of children with other psychiatric disorders. However, this is not the case with explanations mediated by magic-mystical factors.

Distinctive among the findings was the multiplicity of explanations in each case about the origin of the symptoms, something that also seems to be related to time and the tendency for the condition to become chronic: there was a positive correlation between the time course of the disorder and the number of explanations. Also striking was the lack of correlation between these explanations and most of the elements analysed, including variables such as gender or age of the patient, socioeconomic stratum, the characterisation of symptoms, treatments sought and the consequences of the condition. This trend did not include cases explained by external factors which, as mentioned previously, were associated with behavioural problems, fewer symptoms, absence of motor symptoms and greater frequency of “fainting”. The differences in this group of patients are eminently clinical. We were unable to find explanations for the above trend with the information obtained, but, in view of the concurrence of psychological factors and external factors, we would not rule out that it was an artefact from dividing these two factors into two different categories. Whatever the case, it would be an aspect to take into account in future studies.

The fact that no common path was found connecting the conceptions about the origin of the disease, the symptoms and, above all, help-seeking behaviours, suggests that a good part of the process is mediated more by uncertainty and impotence than by clear convictions.

It is striking, however, that the magical/mystical theme is there, whether for the origin of the symptoms, the treatments or both, in eight out of the 10 cases analysed. There is cultural and even neurobiological influence at play here,26 but it could also be related to the high levels of uncertainty and a tendency to conceive the illness or symptom as a product of various factors which have taken possession of the patient, with the patient becoming a silent, passive victim; this is more evident in the analysis of the narratives. We were unable to come to any particular conclusions on this with the information obtained in this study but believe it is an area that merits specific analysis in future research.

ConclusionsThe EMs tended to conform to different theories regarding the origin of the symptoms, but in an unstructured and fragmented way. However, the concept prevails that it is an illness related to a lesion in the central nervous system. Psychosocial factors and magical/mystical explanations are also frequently cited.

The magical–mystical theme is common in the EMs, not only in the explanations for the illness, but also for treatments, and within this model the patient is seen as a victim of magical forces which are acting as a driver of the symptoms.

The concept of emotional “trauma” is a common cause of symptoms in the EMs, where a negative life event causes a break in the normal course of life and generates an emotional impact, and this then acts as a trigger for the symptoms.

Symptom presentation was polymorphic and chronic and included symptoms that go beyond the neurological sphere.

According to the families, the main way the symptoms affected the patients was in their performance at school. However, there were some cases of patients with symptoms which caused no interference, which does seem remarkable.

The consequences in the family environment tended to be less obvious and, in a not insignificant number of cases, without any negative connotations; actually strengthening the bonds within the family.

Treatment plans included several nodal points, with medical care being just one of them. However, these nodal points did not necessarily bear any relationship to how they explained the origin of the symptoms.

This study is merely a first approach to the subject. It would be useful to complement this knowledge with other studies that approach the daily life of both relatives and patients from an ethnographic perspective. It is also important that future studies address the relationship between the symptom, the illness, magical thinking and the belief systems, as well as taking a closer look at the population that attributes the symptoms to traumatic events.

Healthcare has to go beyond the diagnostic process and the treatment of the symptom. It should also include first-hand knowledge about the experiences and suffering of patients and their families. Exploring how they explain their health problems is a first step in achieving care with a more human face.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of people and animalsThe authors state that the procedures followed conformed to the ethical standards of the responsible human experimentation committee and to the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols implemented in their place of work regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingThis work was funded by the Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Innovation (COLCIENCIAS), code 110165745043.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

To Dr José Daniel Toledo Arenas, psychiatrist and epidemiologist, for his help analysing the information, and Dr Carlos Uribe, anthropologist, for his suggestions and contributions.

Please cite this article as: Garcia Mantilla JS, Vasquez Rojas RA. Lo visible y lo menos visible en el padecimiento de un trastorno conversivo en niños y adolescentes. Un estudio cualitativo sobre los modelos explicativos de la enfermedad que ofrecen los cuidadores de niños y adolescentes con trastorno conversivo. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2018;47:155–164.