According to the literature, hospitalised patients with mental disorders have a higher risk of developing cavities and periodontal disease than the general population, associated with the motor difficulty to perform adequate oral hygiene, to the adverse effects caused by drugs for the control of psychiatric symptoms, as well as the lack of oral care and clinical care.

The aim was to carry out a systematic review of the literature on the oral health status of hospitalised patients with mental disorders (MD).

A systematic search of the literature was carried out in PubMed, according to the PRISMA statement methodology, through the MeSh health descriptors “Dental Caries” and “Mental Disorders” in February 2017.

According to the different filters that were applied, 14 articles describing the oral health status were obtained—through the DMF-T index (teeth with cavities, teeth with restorations, missing teeth and teeth with necessary extraction)—of hospitalised patients with MD.

The recognition of the importance of oral health by health professionals, carers and family members should be promoted; the oral cavity should be explored to determine the state of health in addition to instructing patients and support personnel in oral hygiene; mental health institutions should establish an intervention programme to eliminate oral infectious sites and then implement a multidisciplinary preventive programme to maintain oral health according to the MD diagnosis.

De acuerdo a la literatura, los pacientes hospitalizados con trastornos mentales (TM), tienen mayor riesgo a desarrollar caries y enfermedad periodontal que la población general, asociado a la dificultad motora para hacerse una adecuada higiene oral, a los efectos adversos que ocasionan los medicamentos para el control de los síntomas psiquiátricos y a la falta de cuidado oral y atención clínica.

El objetivo era realizar una revisión sistemática de la literatura sobre el estado de salud oral de pacientes hospitalizados con TM.

Se hizo una búsqueda sistemática de la literatura en PubMed, de acuerdo con la metodología de la declaración PRISMA, a través de los descriptores en salud MeSh “Dental Caries” y “Mental Disorders” a febrero de 2017.

De acuerdo a los diferentes filtros que fueron aplicados, se obtuvieron 14 artículos que describieron el estado de salud oral—mediante el índice COP-D (dientes con caries, dientes con restauraciones, dientes perdidos y dientes con extracción mandatoria)—de pacientes hospitalizados con TM.

Se debe promover el reconocimiento de la importancia de la salud oral por parte de los profesionales de la salud, cuidadores y familiares; se debe explorar la cavidad oral para determinar el estado de salud además de instruir a los pacientes y personal de apoyo en higiene oral; las instituciones de salud mental deben establecer un programa de intervención para eliminar focos infecciosos orales y luego implementar un programa preventivo multidisciplinario para mantener la salud oral de acuerdo al diagnóstico del TM.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health as a state of well-being in which the individual is aware of his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to contribute to society.1 This definition of mental health covers psychological and psychosocial capacities for functioning amidst current daily vicissitudes and suffering—that is, the ability to cope with highly emotionally charged situations and the ability to distinguish problems and mental disorders (MDs) with which they are generally supplanted.2

The WHO World Mental Health Survey conducted between 2001 and 2003 in adults from 14 countries across the Americas (Colombia, Mexico and the United States), Europe (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and Ukraine), Africa (Lebanon and Nigeria) and Asia (Japan and separate surveys in Beijing and Shanghai in the People's Republic of China) confirmed that MDs—specifically anxiety, mood disorders, impulse control disorders and substance abuse disorders—are highly prevalent, cause a great deal of disability and often go untreated.3 Comparison of the prevalence of MDs in the countries included in the WHO survey reveals Colombia to occupy one of the top five spots for some MDs.4 Previously, mental health surveys conducted in Colombia in 1993, 1997 and 2003 started from the premise that mental health is defined as being well from an individual and collective perspective. In the 2015 national mental health survey, predisposing factors to the development of MDs were identified through the lens of social determinants, with a view to supporting the development of public policies and interventions in public health that would enable health promotion, prevention of problems and MDs, treatment for these conditions, and social inclusion.5 Therefore, mental health and MDs correspond to highly complex phenomena involving ecological and biopsychosocial aspects related to political, cultural, social and environmental considerations, in addition to psychological, symbolic and biological circumstances.

Thus the natural history of this group of diseases can be modified through general health and public health programmes, in which the contextualisation of MDs includes large numbers of considerations that affect individuals' overall and systemic health status, including their oral health. For that reason, the recommendations given in the latest mental health survey in Colombia included conducting more in-depth studies to determine risk factors and protective factors in people with MDs.6

The WHO defines oral health as the absence of diseases and disorders that affect the mouth (soft-tissue abnormalities, cleft lip and cleft palate, chronic orofacial pain, etc.), the oral cavity (cancer and periodontal disease) and the teeth (caries).7

One of the most prevalent diseases in humans, along with periodontal disease, metabolic syndrome and cancer, is caries (affecting 99% of the global population regardless of sex, age or ethnic group).8 This chronic dental disease of multifactorial origin develops as a result of demineralisation (chemical dissolution) of the hard tissues of the teeth (enamel, dentin and cementum) and, in the absence of therapeutic intervention, progresses towards the destruction of all affected teeth.9,10 In the aetiopathogenesis of caries, bacterial plaque is the most important factor, followed by oral hygiene habits, the susceptibility of the host (human being) and the time that elapses between personal and professional oral hygiene sessions.11 It is important to recognise that carious lesions in an individual's teeth compromise that individual's oral health status. Hence, they could affect one's daily life by causing pain and rendering the main functions of the oral cavity, such as chewing and swallowing, impossible. This leads to decreased appetite, weight loss, difficulty sleeping and psychological and emotional problems (irritability, low self-esteem and a negative outlook on how one is perceived by one's peers).12 Furthermore, lesion progression can cause periapical abscesses, cellulitis and intraoral and extraoral abscesses. In patients with systemic comorbidities, these can in turn cause more serious disease conditions such as cavernous sinus thrombosis, Ludwig's angina or bacterial endocarditis, potentially leading to the individual's death. Therefore, caries is an oral disease that affects overall health, and thus the quality of life of those who suffer from it and those around them.13

Individuals with MDs have quite a high rate of caries, due to changes in behaviour that may limit their awareness of the need for oral care (both personal hygiene and clinical care); motor difficulties in performing suitable oral hygiene; and the adverse effects caused by the medications they take to manage their psychiatric symptoms, including alteration of the normal physiology of the salivary glands (xerostomia), which affects the immune response associated with the mucous membranes, promotes the formation of bacterial plaque, fosters inflammation of the periodontal tissues and increases the likelihood of developing of carious lesions in the teeth.14–16

One method used in epidemiological research to measure the impact of caries on patients with MDs is the decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT) index. This index was developed in 1935 by Klein, Palmer and Knutson during a study of the dental status and need for treatment of children attending elementary schools in Hagerstown (Maryland, United States). The DMFT index corresponds to a numerical value (the number of teeth with caries, the number of teeth with fillings and the number of missing teeth). This describes the relative dental health status of a population using a graduated scale with upper and lower limits, defined and designed to measure risk level, health status severity and needs for restorative or rehabilitative dental treatment. Although the DMFT index has been questioned as it underestimates the actual frequency of caries and treatment needs by not including X-rays as a diagnostic tool, it has proven very useful in indicating past caries (filled teeth and missing teeth) and current caries (teeth with caries and teeth extracted due to crown destruction caused by caries). Hence, it is essential to establish baselines in populations in which epidemiological studies have not been conducted. The DMFT index was subsequently modified to include the number of teeth indicated for extraction, resulting in the decayed, missing, filled and indicated for extraction (DMFX) index.17

The average DMFX index value for an individual (individual index) is obtained from the sum of teeth with caries, filled teeth and missing teeth (Table 1). For a study population (community index), the sum of teeth with caries, filled teeth and missing teeth is divided by the total number of individuals examined. Once the absolute value of the index is obtained, the level of severity (in terms of risk) is determined: 0 = no risk; 0.1–1.9 = very low risk; 2.0–2.8 = low risk; 2.9–5.2 = medium risk; 5.3 = 7.3 = high risk; and >7.3 = very high risk.17,18 An index of zero indicates no past caries and therefore no risk or very low risk. However, it obliges health professionals to reinforce oral hygiene measures and establish and maintain a specific prevention programme to maintain this condition on an ongoing basis throughout the individual's life. An index of more than zero can be interpreted in one of the following ways: 1) If cavitated caries is clearly represented in the "decayed teeth" component, given that the diagnosis is timely, immediate restorative dental treatment as well as reinforced oral hygiene promotion and prevention efforts must be done. 2) If the most strongly represented component is “filled teeth”, the evidence points to prior access to restorative dental treatment but a failure to implement early effective oral health promotion and prevention programmes. 3) If the component with the strongest representation is “missing teeth”, clearly dental care was provided late (or not at all), and therefore the treatment plan has resulted in extraction of teeth with crown destruction and destruction of retained roots (or root debris).18

DMFX index recording support atlasa.

| Healthy tooth | |

| Clinically healthy tooth with no evidence of treated or untreated caries: | |

| • Tooth with no change in enamel translucency after drying for more than five seconds (with cotton, gauze, or air). | |

| Tooth with non-cavitated caries | |

| White spot visible on: | |

| • Occlusal surface (pits and fissures). | |

| • Vestibular surface (cervical third). | |

| • Interproximal surfaces (point of contact with the gums). | |

| They are characterised by retention of bacterial plaque. Loss of enamel integrity without dentin exposure as well as teeth with pit and fissure sealants with evidence of non-cavitated caries should also be considered according to the above criteria. | |

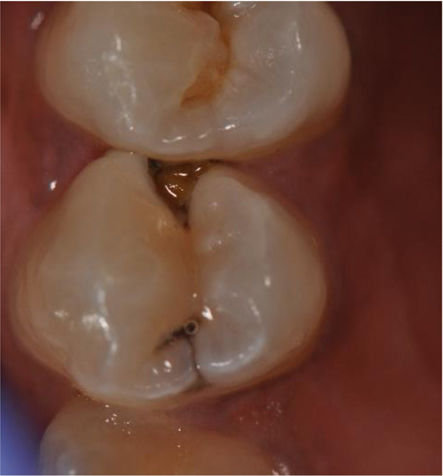

| Tooth with cavitated caries | |

| Loss of tooth structure including: | |

| • Detectable cavity (lesion in a pit, fissure or smooth surface with visible signs of cavitation and eroded, softened enamel) with a base bordering on the dentin. | |

| • Extensive cavity (loss of tooth structure with a cavity involving at least half the tooth surface) that may include dentin and pulp. | |

| • Tooth with a cavity filled with temporary cements (phosphate, eugenolate and coltosol). | |

| • Tooth with frank cavitation and retained caries. | |

| Teeth that have partially or completely lost their permanent fillings and do not present active caries. | |

| Tooth with a filling due to caries | |

| Tooth with one or more fillings (restorations) with permanent materials without primary or secondary (recurrent) caries: | |

| • Amalgam. | |

| • Resin. | |

| • Glass ionomer. | |

| • Metal, metal–ceramic or ceramic crown. | |

| • Provisional acrylic crowns. | |

| Missing tooth due to caries | |

| Tooth not present at the time of examination, having been extracted due to caries. Teeth missing for a reason other than caries are not included. | |

| • Missing tooth due to extraction. | |

| • Retained roots due to crown destruction. | |

| Tooth indicated for extraction | |

| This does not figure in the DMFX index, but it is used to estimate individuals' unmet treatment needs. It includes: | |

| • Retained roots. | |

| • Crown destruction. | |

In general terms, individuals with MDs experience greater deterioration of their physical condition in comparison to the general population. In addition, their risk of developing oral diseases such as caries and periodontal disease increases considerably, due to the physical difficulties they face in performing suitable oral hygiene, poor diet and the evident depersonalisation of the individual (separation of identity and physical existence). In the context of the oral cavity, this leads to tooth loss (hence their greater need for restorative and rehabilitative dental treatments than the general population). In a systemic context, this increases the risk of developing or exacerbating certain diseases, associated with chronic inflammation and increased loss of immune system tolerance.19,20 These diseases include metabolic syndrome (cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus and obesity), joint diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and spondyloarthritis), urogenital diseases (kidney failure and prostate cancer) and conditions during pregnancy (pre-eclampsia), which in turn are comorbidities associated with MDs.19–25 However, oral health has never been considered a priority in patients with MDs, even though there is sufficient scientific evidence to identify oral diseases as risk indicators for systemic diseases, and even though poor oral health has a strong impact on quality of life, daily functioning, social inclusion and self-esteem.19 With this in mind, a group of researchers conducted a search for evidence in the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register of Trials, based on regular searches of MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL and PsycINFO. They concluded that, as of 2011, no clinical trials focusing on oral health care counselling in patients with MDs could be identified.25

Although a 2013 study suggested a protocol for conducting clinical trials of oral health interventions in hospitalised patients with chronic MDs, to date, no controlled clinical trial has been reported.26 As late as 2015, a meta-analysis using the MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Embase electronic literature databases identified 25 studies since 1990 having correlated oral health with mental health. The report concluded that patients hospitalised for MDs have higher rates of decayed teeth, filled teeth and missing teeth than the general population.27,28

Therefore, the objective of this article was to conduct a systematic review of the literature on the oral health status of hospitalised patients with MDs.

Materials and methodsThe question “What is the relationship between mental illness and tooth decay” was entered in MeSH on Demand, yielding the following MeSH terms: “Dental Caries” and “Mental Disorders”. These terms were then used to conduct a systematic search in MEDLINE via PubMed using the “AND” Boolean operator. Original research articles that used the DMFX index to report the oral health status of hospitalised patients with MDs up to February 2017 were included.

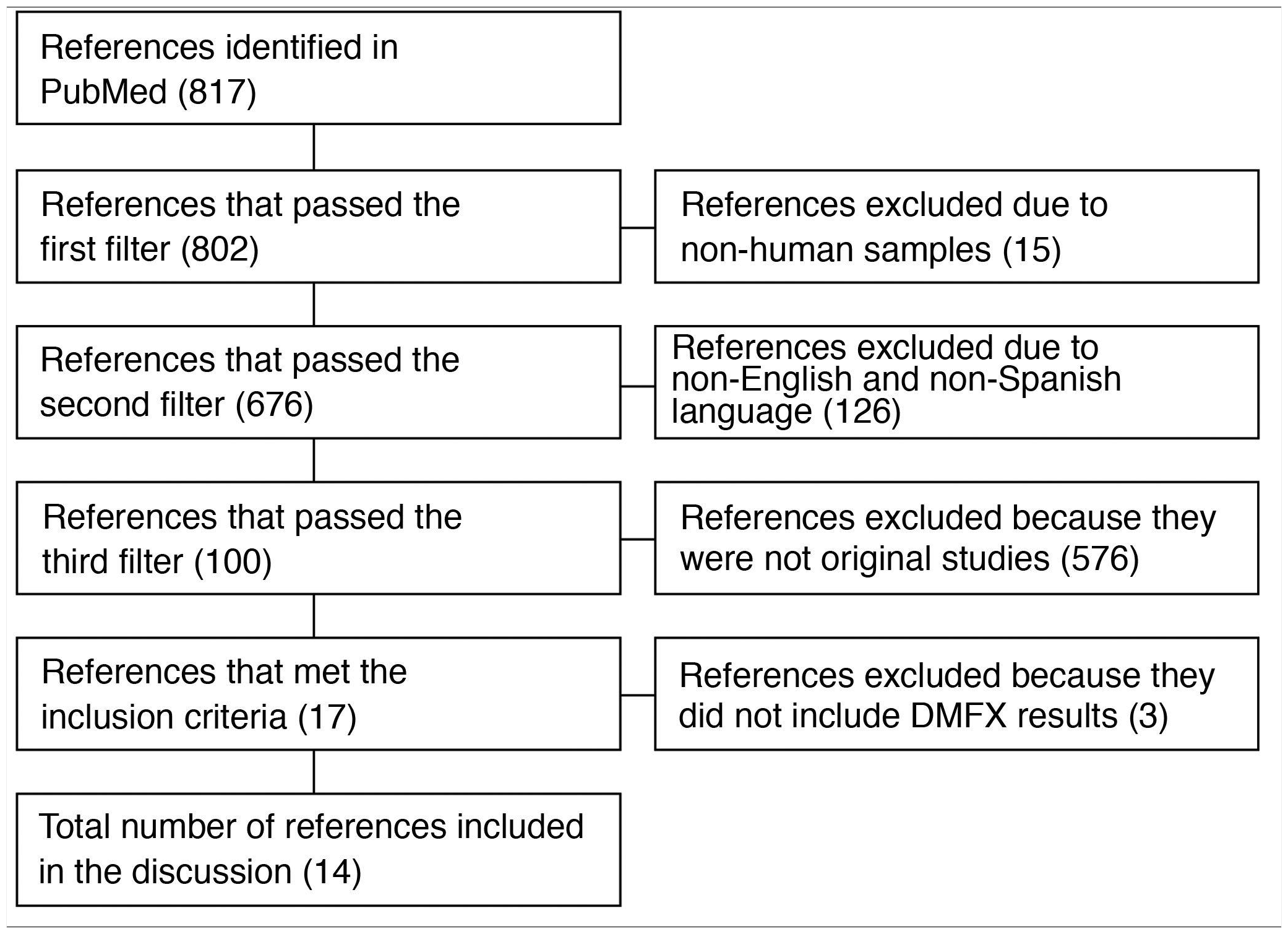

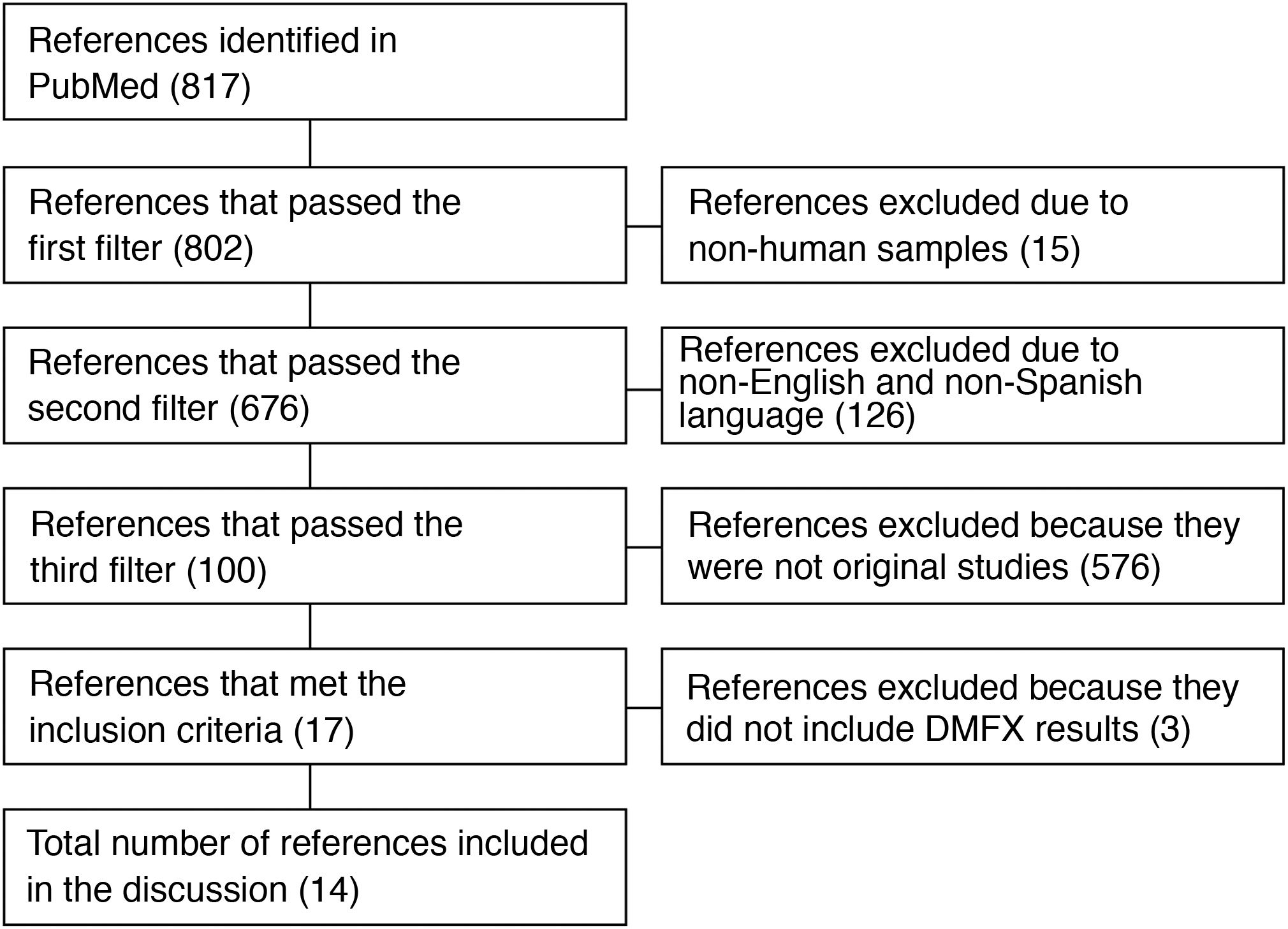

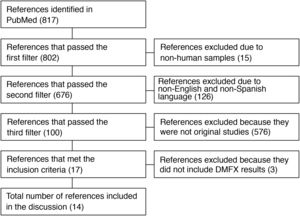

ResultsAccording to the methodology in the PRISMA declaration29 (Table 2), 817 articles were initially retrieved in PubMed. These were then filtered by “Humans”, resulting in 802 articles. Next, “Language” filters (English and Spanish) were applied, leaving 676 articles, and “Article Type” was limited to Clinical Trial, Controlled Clinical Trial, Comparative Study or Observational Study), narrowing the results to 100 articles. Finally, the titles and abstracts were read, 14 articles were found to meet the inclusion criteria (description of oral health status using the DMFX index) and the discussion was prepared using these articles (Table 3).

Flow chart for selecting the references included in the discussion according to the methodology in the PRISMA Declaration.29

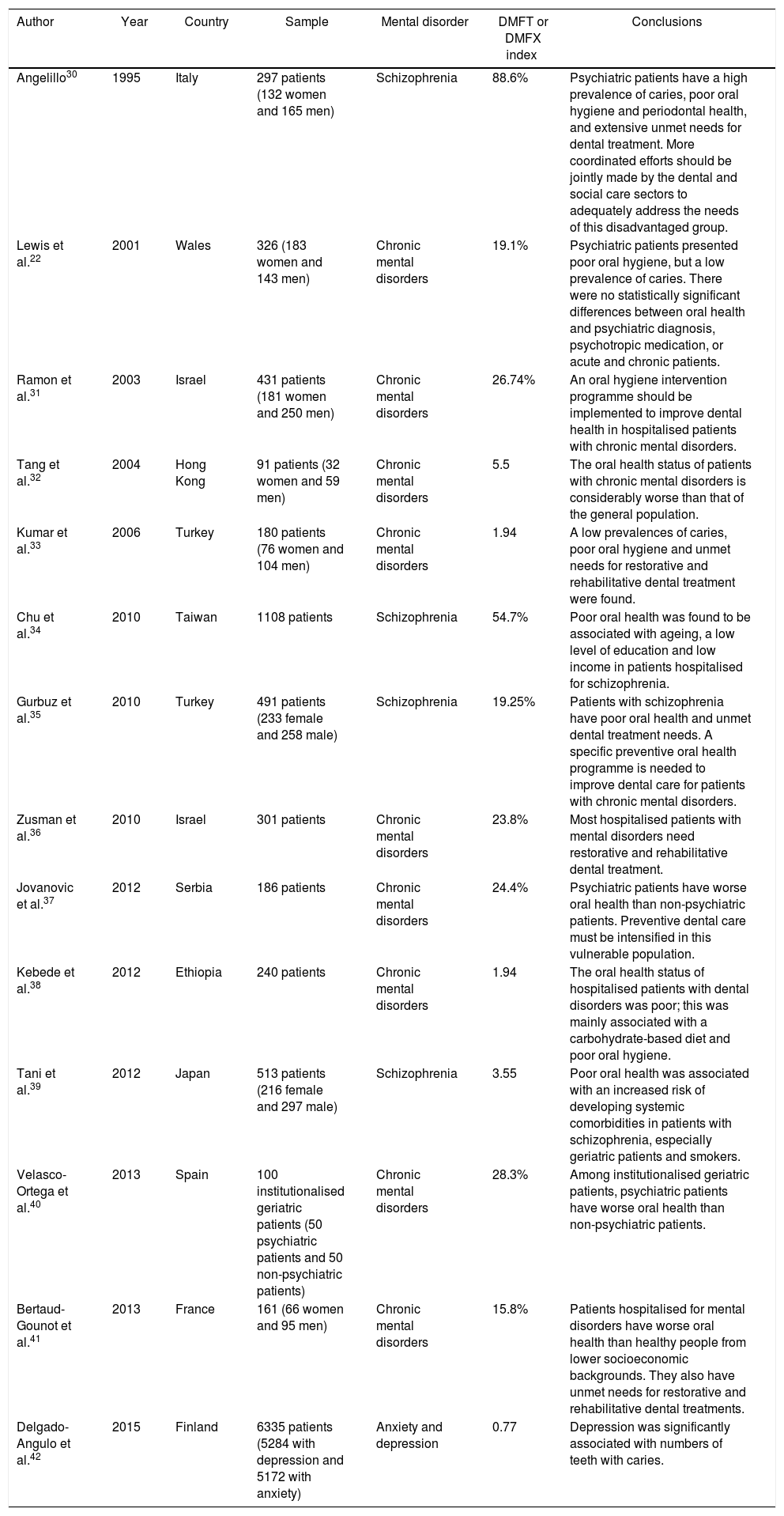

DMFT index or DMFX index studies in hospitalised patients with mental disorders identified in PubMed.

| Author | Year | Country | Sample | Mental disorder | DMFT or DMFX index | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angelillo30 | 1995 | Italy | 297 patients (132 women and 165 men) | Schizophrenia | 88.6% | Psychiatric patients have a high prevalence of caries, poor oral hygiene and periodontal health, and extensive unmet needs for dental treatment. More coordinated efforts should be jointly made by the dental and social care sectors to adequately address the needs of this disadvantaged group. |

| Lewis et al.22 | 2001 | Wales | 326 (183 women and 143 men) | Chronic mental disorders | 19.1% | Psychiatric patients presented poor oral hygiene, but a low prevalence of caries. There were no statistically significant differences between oral health and psychiatric diagnosis, psychotropic medication, or acute and chronic patients. |

| Ramon et al.31 | 2003 | Israel | 431 patients (181 women and 250 men) | Chronic mental disorders | 26.74% | An oral hygiene intervention programme should be implemented to improve dental health in hospitalised patients with chronic mental disorders. |

| Tang et al.32 | 2004 | Hong Kong | 91 patients (32 women and 59 men) | Chronic mental disorders | 5.5 | The oral health status of patients with chronic mental disorders is considerably worse than that of the general population. |

| Kumar et al.33 | 2006 | Turkey | 180 patients (76 women and 104 men) | Chronic mental disorders | 1.94 | A low prevalences of caries, poor oral hygiene and unmet needs for restorative and rehabilitative dental treatment were found. |

| Chu et al.34 | 2010 | Taiwan | 1108 patients | Schizophrenia | 54.7% | Poor oral health was found to be associated with ageing, a low level of education and low income in patients hospitalised for schizophrenia. |

| Gurbuz et al.35 | 2010 | Turkey | 491 patients (233 female and 258 male) | Schizophrenia | 19.25% | Patients with schizophrenia have poor oral health and unmet dental treatment needs. A specific preventive oral health programme is needed to improve dental care for patients with chronic mental disorders. |

| Zusman et al.36 | 2010 | Israel | 301 patients | Chronic mental disorders | 23.8% | Most hospitalised patients with mental disorders need restorative and rehabilitative dental treatment. |

| Jovanovic et al.37 | 2012 | Serbia | 186 patients | Chronic mental disorders | 24.4% | Psychiatric patients have worse oral health than non-psychiatric patients. Preventive dental care must be intensified in this vulnerable population. |

| Kebede et al.38 | 2012 | Ethiopia | 240 patients | Chronic mental disorders | 1.94 | The oral health status of hospitalised patients with dental disorders was poor; this was mainly associated with a carbohydrate-based diet and poor oral hygiene. |

| Tani et al.39 | 2012 | Japan | 513 patients (216 female and 297 male) | Schizophrenia | 3.55 | Poor oral health was associated with an increased risk of developing systemic comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia, especially geriatric patients and smokers. |

| Velasco-Ortega et al.40 | 2013 | Spain | 100 institutionalised geriatric patients (50 psychiatric patients and 50 non-psychiatric patients) | Chronic mental disorders | 28.3% | Among institutionalised geriatric patients, psychiatric patients have worse oral health than non-psychiatric patients. |

| Bertaud-Gounot et al.41 | 2013 | France | 161 (66 women and 95 men) | Chronic mental disorders | 15.8% | Patients hospitalised for mental disorders have worse oral health than healthy people from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. They also have unmet needs for restorative and rehabilitative dental treatments. |

| Delgado-Angulo et al.42 | 2015 | Finland | 6335 patients (5284 with depression and 5172 with anxiety) | Anxiety and depression | 0.77 | Depression was significantly associated with numbers of teeth with caries. |

Out of all the studies included, one took place in the 1990s and nine were conducted in the past 10 years; the most prevalent MDs in them were dementia, schizophrenia and depression. No reports in Colombia were found. All the articles concluded that the oral health of hospitalised psychiatric patients is worse than that of non-psychiatric patients in terms of rates of caries, filled teeth and missing teeth, pointing to deficits in both preventive and therapeutic dental care. Similarly, all the authors agreed upon the importance of implementing an oral health prevention programme in mental health hospitals in order to reduce the impact of the relationship between oral diseases, MDs and systemic comorbidities and to meet restorative and rehabilitative dental treatment needs in a satisfactory matter.

Regarding the results for the DMFT and DMFX indices, in three studies, the relationship between mental health status and the development of caries was not statistically significant; this was associated with the fact that the sample was not at risk of developing caries based on their prior experiences43 or was at low risk thereof.33,38 Finally, one study had a sample at medium risk39 and another had a sample at high risk.36 In the remaining nine studies, numbers of filled, decayed and missing teeth were expressed in terms of percentages and varied widely, being low in one study,40 relatively low in five studies,23,31,35–37,40 relatively high in one study34 and very high in one study.30

DiscussionOral health is essential to human quality of life, not only from an oral and systemic health perspective, but also from a socio-affective point of view, since it affects verbal communication, oral sexuality and social acceptance. Hence, it is an integral part of the general health of hospitalised psychiatric patients.30–33 However, this specific population is at higher risk of developing caries and periodontal diseases; this higher risk is associated with their limited awareness of the importance of regular oral hygiene and the lack of continuity and timeliness of their professional care.19,20 In addition, the studies included in this review identified apathy (because the perception of the dental treatment needs of hospitalised psychiatric patients is low) and a lack of concern and interest (due to a failure to consider the potential for inflammation of periodontal tissues caused by drug treatment) on the part of health professionals (psychiatrists, internal medicine physicians and nurses) and caregivers (nursing assistants and administrative staff) at hospitals, which have no established oral hygiene programme and do not promote access to dental services.31,32,42

Thus, the link between MDs and caries has been attributed to patients' inability to care for themselves, resulting in inadequate oral hygiene that interferes with the management of bacterial plaque, in addition to sialorrhoea, xerostomia, ulceration of the oral mucosa and gingival hyperplasia, caused by psychotropic drugs (such as tricyclic antidepressants, mood stabilisers, anticonvulsants and psychostimulants), increased pH and alteration of the first barrier of immunological defence—all of which are recognised aetiopathogenic factors in caries.15,40,43–47 In addition, motor abnormalities such as orofacial dystonia and mandibular dyskinesia, caused both by patients' mental status and the use of these drugs, likewise interfere with adequate oral care.44 That is why the DMFT index values from the studies included in this report show that hospitalised patients with MDs may be at higher risk of developing caries than the general population.24,27. The high prevalence of caries can lead to the loss of affected teeth, such that people with MDs are 2.7 times more likely to lose all their teeth compared to the general population.27 In this regard, the most strongly represented component of the DMFT and DMFX indices—even when these have a low value—is missing teeth, because, in most cases, once caries has been diagnosed, treatment results in tooth extraction; this is associated with a lack of timely dental care.24 In these cases, according to the Colombian Ministry of Social Protection, the intervention should focus on improving oral hygiene habits, managing persistent caries and providing timely care to prevent further tooth loss.17

Since 1982, the WHO has published recommendations to improve socio-psychological aspects of oral health in psychiatric patients, including meeting prosthetic and aesthetic needs; relieving pain; removing bacterial plaque and managing the formation thereof; monitoring and managing dental occlusion so that facial harmony is unaffected; and managing defects caused by dental, buccal and maxillofacial abnormalities. Nevertheless, comprehensive dental care plans have not been generally established.45 This is despite the literature showing that MDs and caries are two diseases that affect health and quality of life, and that when individuals have both diseases, they face more obstacles to achieving optimal levels of mental, physical and social functioning—including relationships as well as perceived health, satisfaction, well-being and quality of life—with substantial effects on rates of use of healthcare services and on healthcare costs. Hence, they constitute a public health problem, given their high prevalence and incidence in the population.46,47

Thus, the studies of oral health in hospitalised patients with MDs included in this review have recommended that: 1) Recognition of the importance of oral health should be promoted among health professionals (other than dentists, oral hygienists and dental assistants) and supportive family members. 2) It is important for health professionals (physicians and nurses) and support staff (nursing assistants, paramedics and caregivers) to know how to examine the oral cavity in order to determine the health of the teeth and periodontal tissues, as well as instruct patients in proper oral hygiene. 3) Mental health institutions must establish an intervention programme to eliminate foci of oral infection and then implement a multidisciplinary prevention programme to maintain oral health throughout the duration of hospitalisation, depending on MD diagnoses. 4) Patients with MDs who have had caries and who also have systemic comorbidities such as obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart disease, atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, prostate cancer or kidney dysfunction, including women who are pregnant and may develop pre-eclampsia, should be followed up. 5) Healthcare settings such as individual care, group care, care in workshops and home visits can be leveraged to promote suitable oral hygiene habits.29,30,33–39,41,42

In conclusion, having a goal of preserving quality of life by preventing and treating diseases is a precept of the health sciences. The following are coherent with this precept and must be prioritised: the formation of multidisciplinary teams who conduct studies to identify the risk of developing caries in hospitalised patients with MDs, taking into account the probability (risk indicators) that systemic involvement is directly linked to the aetiopathogenesis of the two diseases based on: 1) socioeconomic factors (social exclusion, unemployment, limited resources, lack of health knowledge and inability to access dental care on a regular basis); 2) factors related to general health (physical handicaps, systemic diseases and MDs themselves); and 3) epidemiological factors (belonging to a population with a high incidence of caries, being a member of a family with a high incidence of caries and having a personal history of caries).

FundingThis original article is a result of the research project "Estado de salud dental de un grupo de pacientes hospitalizados de una institución de salud mental de Cali (Colombia)" [Dental health status of a group of hospitalised patients from a mental health institution in Cali (Colombia)], which was funded by the 2018-2019 Internal Call of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Cali [Cali Pontifical Javierian University].

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data availabilityData will be made available on request.

This review article was prepared as part of the research project “Estado de salud dental de un grupo de pacientes hospitalizados de una institución de salud mental de Cali (Colombia)” [Dental health status of a group of hospitalised patients from a mental health institution in Cali (Colombia)], funded by the 2018-2019 Internal Call of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Cali [Cali Pontifical Javierian University].

Please cite this article as: Castrillón E, Castro C, Ojeda A, Caicedo N, Moreno S, Moreno F. Estado de salud oral de pacientes hospitalizados con trastornos mentales: Revisión sistemática de la literatura. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2022;51:51–60.