To determine the association between Internet addiction (IA) and academic performance in dental students at the University of Cartagena.

Material and methodsA cross-sectional study was conducted in 402 students included through non-probabilistic sampling who answered an anonymous and self-reporting questionnaire that included socio-demographic variables, academic performance (last semester overall grade), presence of IA (Young's Test) and covariates related to IA based on academic performance. Data were analysed by means of proportions, relationships between variables with the χ2 test and strength of association was estimated with odds ratios (OR) using nominal logistic regression.

ResultsApproximately 24.63% of the students used the Internet much less than the average population, but 75.3% had IA; 73.13% of cases were considered mild and 2.24% moderate. There were no severe cases. Around 5.2% had poor academic performance. In multivariate analysis, the model that best explained IA in relation to academic performance was: studying in lower-level courses (OR=0.54; 95% CI, 0.32–0.91); studying in a different places of the house (OR=3.38; 95% CI, 1.71–6.68); not using laptop for studying (OR=0.41; 95% CI, 0.19–0.89), chatting on mobile phone (OR=2.43; 95% CI, 1.45–3.06); and spending more than 18min on mobile phone while studying (OR=3.20; 95% CI, 1.71–5.99).

ConclusionsAcademic performance was not associated with AI. However, studying in lower-level courses, in a different place of the house, not using laptop to study, and spending more than 18min answering their mobile phone and chatting on mobile phone while studying were covariates statistically associated with IA.

Estimar la asociación entre la adicción a internet (AI) y el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes de Odontología de la Universidad de Cartagena.

Material y métodosEstudio de corte transversal en 402 estudiantes, seleccionados de modo no probabilístico, que respondieron a un cuestionario anónimo autoaplicado que incluía variables sociodemográficas, rendimiento académico (promedio acumulado del último semestre), presencia de AI (test de Young) y variables relacionadas con la AI en función del rendimiento académico. Los datos se analizaron a partir de proporciones, relaciones entre variables con test de la χ2, y la asociación se obtuvo por razones de disparidad (OR) a través de regresión logística nominal.

ResultadosEl 75,3% de los estudiantes mostraban AI; el 24,63% utilizaba internet mucho menos que la población promedio; el 73,13% mostraba una AI leve; el 2,24%, una AI moderada y no hubo casos de AI grave; el 5,2% tenía bajo rendimiento académico. En el análisis multivariable, el modelo que mejor explica la AI en relación con el rendimiento académico fue: estudiar en semestres inferiores (OR=0,54; IC95%, 0,32-0,91), estudiar en lugar distinto de la casa (OR=3,38; IC95%, 1,71-6,68), usar elemento no portátil para estudiar (OR=0,41; IC95%, 0,19-0,89), chatear por celular (OR=2,43; IC95%, 1,45-3,06) y demorar más de 18min (OR=3,20; IC95%, 1,71-5,99) mientras se estudia.

ConclusionesEl rendimiento académico no se asocia con la AI. Sin embargo, estudiar en semestres inferiores, en un lugar distinto de la casa, emplear elementos no portátiles para estudiar e invertir más de 18min en contestar el celular y chatear mientras se estudia son covariables estadísticamente asociadas con la AI.

The Internet is a tool which facilitates communication, given that it is widely accessible (computers, mobile phones and digital tablets) and it has huge potential to pass on information, exchange content and establish contact with other people.1 This can be beneficial for the quality of life of individuals,2 but it may represent a threat when its use is not controlled.3

The number of Internet users has increased significantly in recent years.4 According to Internet World Stats,4 there are currently approximately 3,731,973,423 Internet users in the world, with Asia being the continent with the highest Internet penetration rate and China, India and the United States being the countries which top the list of the largest number of users. In Latin America, Brazil tops the list,4 while in Colombia the Internet penetration rate is 58.6%. 76% of young people have their own mobile phone with minutes and data, and, by gender, it is used almost with the same frequency,5 although the reasons vary.

Its inappropriate use is likely to give rise to Internet addiction (IA),6 also known as “pathological Internet use”, “compulsive Internet use”, “net addiction” or “cyber addiction”.7,8 IA is a new type of non-chemical addiction, characterised by excessive or poorly controlled concerns of impulses or behaviours related to the use of computers and access to the Internet which lead to deterioration or psychological anguish.9 IA is a hobby which generates dependence and takes away freedom from the human being, by stretching their field of awareness and restricting the extent of their interests and intervening negatively in daily activities, as it determines taking the Internet and the virtual world as a priority before their real life.9 The condition has attracted growing attention from researchers, and this attention has been parallel to the increase in access to computers (and the Internet).1 To date, IA has not been included among the diagnosable disorders of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association.9 Nevertheless, it was a long time ago that researchers pointed out the existence of symptoms and effects that justify talking about a psychosocial dysfunction due to Internet use.10 The following effects have been suggested: sleep disturbance11 and altered mood12; the feeling of guilt13; negative interference in social life14; and decline in academic performance,15 in particular in adolescents and young people, which compromises their quality of life.16

The following are reported as being predisposing factors for IA: being under the age of 21 years; having health problems; having family problems; suffering from discrimination and living far away from the family environment.17,18 With regard to Internet use, an association has been found whereby women are the more prevalent users, as well as its use for leisure purposes.17 Studies on IA have focussed their efforts on the adolescent and university population, as they are the groups most susceptible to suffering from loss of self-control.19 An association with IA has been found in students of degrees outside the field of health17; however, medical and dental students are also a vulnerable population, taking into account the need to permanently consult the Internet in order to achieve their academic goals and keep up to date with the changes in health systems.6 Gedam et al.6 reported that 2.3% of dental students suffer from this addiction6; Waqas et al.20 described a total prevalence of 6.1% among medical and dental students20 and Nath et al.21 reported that 46.8% of medical students were at greater risk of IA, associated with more years of exposure to the Internet, always being on line and being male, which resulted in poor academic performance at university and a feeling of moodiness, anxiety and depression.

Previous studies on Internet use in university students have been published in Colombia; they report a prevalence of IA or problematic use of 12%, consistent with the literature,1 but there are few local studies which give an account of epidemiological indicators on IA in dental students and their relationship with academic performance, taking into account that some studies report poor academic performance in dental students and that this corresponds to a multicausal process.22,23 Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of IA and its association with academic performance in dental students at the Universidad de Cartagena [University of Cartagena].

Material and methodsAn analytical cross-sectional study was performed in a target population of 440 dental students at the Universidad de Cartagena (Colombia) during the second academic period of 2015; it had the approval of the Institution's Independent Ethics Committee. A census was performed, which obtained a response rate of 91.3%, and those who met the inclusion criteria participated. The criteria were: being enrolled and academically active between the 2nd and 10th semesters and taking part voluntarily in the study through the signing of a written informed consent form. The exclusion criteria were: being a minor and a student with diagnosed or treated mental disorders identified by the institution (Welfare Committee). A final population of 402 students was obtained.

In order to guarantee the confidentiality of the information without violating the subjects’ privacy, a blinded ballot box was used to store the information collection records. It was also explained that their participation in the study would not represent any risk to them staying on at the university. These aspects are supported in international provisions (Declaration of Helsinki – Edinburgh Amendment 2000 – and Colombian regulations – resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health).

Information was gathered using an anonymous self-assessment questionnaire that contained 20 multiple-choice questions with only one response, theoretically designed and with their face validity having been evaluated by three expert judges, taking into account their relevance, the adequacy of the categories, plausibility, semantics, syntax and the ordering of the items. The form contained the following information with their respective categories: sociodemographic characteristics: age (adolescent [18–19 years]; young adult [20–44 years]); gender (male; female); academic semester or cycle (higher-level: sixth to tenth; lower-level: first to fifth); origin (rural; urban); and socioeconomic stratum (low [strata 1, 2, 3], high [strata 4, 5, 6]). Aspects related to academic performance such as cumulative average according to student academic regulations of the institution at the time of the data collection (low, qualification ≤2.99; high ≥3.0), studying alone or accompanied (alone; accompanied); study time per day (≤2h; >2h); self-perception of general distraction when studying (yes; no); place of study (at home; another location) and study devices (non-electronic; electronic; portable; not portable) were evaluated. With regard to the Internet-related variables, addiction was evaluated using Young's Internet Addiction Test (IAT).8 Proposed by Young in 1998, it is one of the most-used tests in clinical practice and in research in IA settings and consists of a 20-item questionnaire with response options on a Likert scale (0=never; 1=rarely; 2=occasionally; 3=often; 4=very often; and 5=always).8 The Spanish version24 was used for this study. The minimum score is 20 and the maximum score is 100. Participants with 20–49 points are classified as users who exceed Internet use but control it (mild addiction); participants with 50–79 points are classified as users with occasional problems due to excessive Internet use (moderate addiction), and participants with 80–100 points as users with frequent and significant problems due to Internet use (severe addiction).24 This test has been translated and validated in Spanish and its construct validity has been studied with an internal consistency of 0.8924 and 0.9125 and its factor validity with RMSEA=0.063 (90% confidence interval [90% CI], 0.055–0.071); CFI=0.921; TLI=0.957; SRMR=0.049.25 For the bivariate analysis the IA variable was dichotomised as follows: 1, mild, moderate or severe addiction (≥20 points), and 0, no addiction (≤19 points), according to IA risk taking into account the categories generated by the test. Other variables related to Internet use and equipment use were also investigated, such as Internet use time (≤2h; >2h)26; Internet use purpose (academic; non-academic); feeling that the Internet has impaired academic performance (yes; no); chatting on a mobile phone while at university (yes; no); chatting while studying (yes; no); time spent answering a mobile phone while studying (≤18min.; >18min., according to the mean obtained); use of a mobile phone while in class (yes; no); purpose of using a mobile phone in classes (academic; non-academic); mobile phone service plan (only minutes; data and minutes); conflicts with people due to Internet use (family members; non-family members).

ProcedureThe application of the instrument was subject to a pilot test with a group of students with similar characteristics. Two research assistants trained by the principal investigator participated as interviewers. They requested the voluntary collaboration of the students and guaranteed the anonymity and confidentiality of the information. Furthermore, the questionnaires passed through auditing and monitoring phases, which included review by the investigators during the data collection to evaluate the adherence of the interviewers to the protocols.

Statistical analysisSTATA 12.0® for Windows (StataCorp.; Texas, United States of America) was used to analyse the information. The data were analysed based on the descriptive statistics, with means±standard deviation for the quantitative variables. For the qualitative variables, IA proportions were calculated, as well as demographic and academic factors. For the relationships between IA categories and sociodemographic variables, variables related to academic performance and Internet use, χ2 tests with a 95% confidence interval were performed. To estimate the strength of associations between the dependent variable (IA) and other independent variables, the reasons for disparity (odds ratio [OR]) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated, with regression-adjusted estimators. For the multivariate analysis, nominal logistic regression was used with inclusion in the models of factors which showed p<0.10 in the bivariate analysis. Models were put together based on the exclusion of each one of the variables in a stepwise regression process according to the recommendations of Greenland.27 In addition, the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was reported,28 with the purpose of demonstrating the significance of the best model from p>0.10.

Psychometric properties of the Internet addiction testThrough the exploratory factor analysis, the structure of factors for the IAT was estimated in the context of this study by means of an estimation method of the main factors with oblique rotation (promax). Furthermore, through a scree plot, the number of factors to be retained was determined and the proportion of variance explained. Inspection of the sedimentation graph shows better performance than other criteria (Kaiser: eigenvalues>1).29,30

To determine the construct validity (CV), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used, evaluating the model adjustment obtained in the exploratory phase. Subsequently, adjustment indices for this model, χ2 and degrees of freedom (df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its 90% CI, comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were obtained. Using the criteria proposed by Hu and Bentler, it was determined as acceptable if the adjustment of the model was: χ2p>0.05; RMSEA≤0.06; CFI≥0.95 and TLI≥0.95.31 Finally, the internal consistency was estimated with Cronbach's coefficient alpha and it was evaluated with the criteria proposed by Kline: acceptable (0.60–0.70), good (0.70–0.90) and excellent (≥0.90).32

The descriptive and inferential analysis and exploratory factor analysis were performed with Stata v.13.2 for Windows (StataCorp.; College Station, Texas, United States of America) and the confirmatory factor analysis was performed with MPlus v.7.11 (Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, California, United States of America).

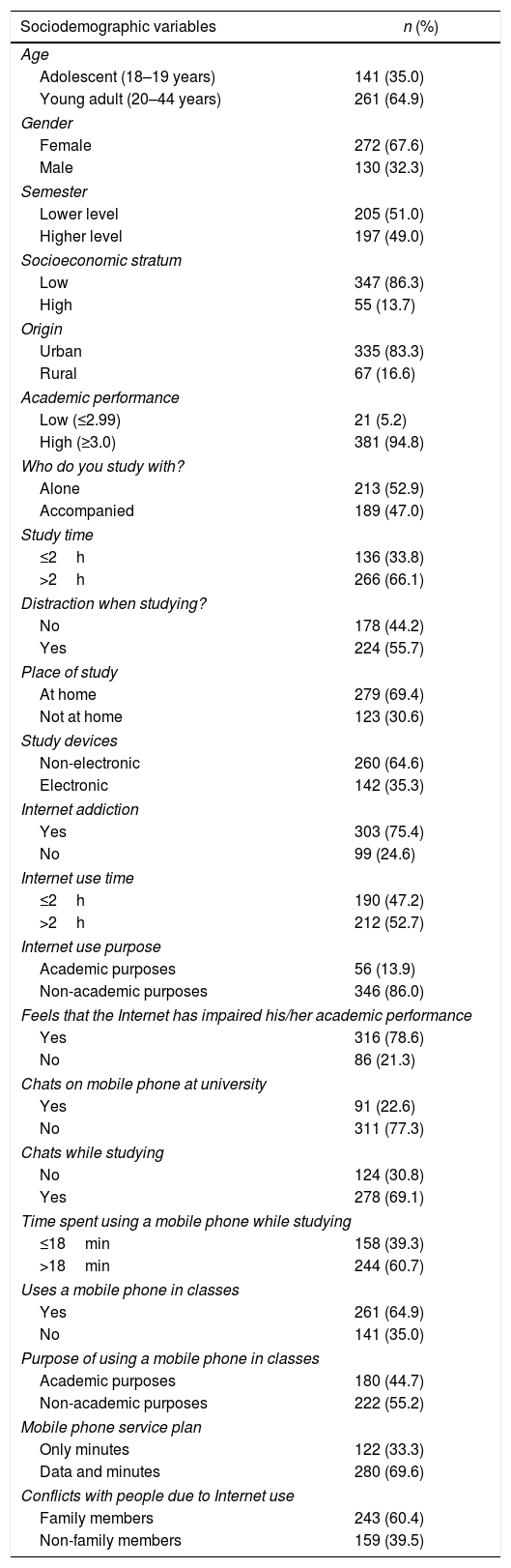

ResultsA total of 402 students participated with a mean age of 20.5±1.1 (interval 16–31) years; 64.9% were young adults; 67.6% were males and 51% were studying lower-level courses (non-clinical cycle) (Table 1). In relation to academic performance and related variables, 21 students (5.22%) underachieved; 66.1% spent more than 2h per day studying and 64.6% did not use electronic devices to study (Table 1).

Sociodemographic variables, academic performance, Internet addiction and variables related to Internet use in dental students at the Universidad de Cartagena, 2015.

| Sociodemographic variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Adolescent (18–19 years) | 141 (35.0) |

| Young adult (20–44 years) | 261 (64.9) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 272 (67.6) |

| Male | 130 (32.3) |

| Semester | |

| Lower level | 205 (51.0) |

| Higher level | 197 (49.0) |

| Socioeconomic stratum | |

| Low | 347 (86.3) |

| High | 55 (13.7) |

| Origin | |

| Urban | 335 (83.3) |

| Rural | 67 (16.6) |

| Academic performance | |

| Low (≤2.99) | 21 (5.2) |

| High (≥3.0) | 381 (94.8) |

| Who do you study with? | |

| Alone | 213 (52.9) |

| Accompanied | 189 (47.0) |

| Study time | |

| ≤2h | 136 (33.8) |

| >2h | 266 (66.1) |

| Distraction when studying? | |

| No | 178 (44.2) |

| Yes | 224 (55.7) |

| Place of study | |

| At home | 279 (69.4) |

| Not at home | 123 (30.6) |

| Study devices | |

| Non-electronic | 260 (64.6) |

| Electronic | 142 (35.3) |

| Internet addiction | |

| Yes | 303 (75.4) |

| No | 99 (24.6) |

| Internet use time | |

| ≤2h | 190 (47.2) |

| >2h | 212 (52.7) |

| Internet use purpose | |

| Academic purposes | 56 (13.9) |

| Non-academic purposes | 346 (86.0) |

| Feels that the Internet has impaired his/her academic performance | |

| Yes | 316 (78.6) |

| No | 86 (21.3) |

| Chats on mobile phone at university | |

| Yes | 91 (22.6) |

| No | 311 (77.3) |

| Chats while studying | |

| No | 124 (30.8) |

| Yes | 278 (69.1) |

| Time spent using a mobile phone while studying | |

| ≤18min | 158 (39.3) |

| >18min | 244 (60.7) |

| Uses a mobile phone in classes | |

| Yes | 261 (64.9) |

| No | 141 (35.0) |

| Purpose of using a mobile phone in classes | |

| Academic purposes | 180 (44.7) |

| Non-academic purposes | 222 (55.2) |

| Mobile phone service plan | |

| Only minutes | 122 (33.3) |

| Data and minutes | 280 (69.6) |

| Conflicts with people due to Internet use | |

| Family members | 243 (60.4) |

| Non-family members | 159 (39.5) |

The total prevalence of IA was 75.3% (95% CI, 71.0–79.0%) (303 students); 24.63% (95% CI, 20.0–28.0%) (99 students) use the Internet a lot less than the average population; 73.13% (95% CI, 68.0–77.0%) (294 students) were considered as cases of mild addiction and 2.24% (95% CI, 0.7–3.6%) (9 students) as cases of moderate addiction. No cases of severe addiction were identified. Moreover, 52.7% browse the Internet for more than 2h, but 86.0% do so for non-academic purposes; 78.6% feel that Internet use has impaired their academic performance and 69.1% chat on a mobile phone while studying (Table 1).

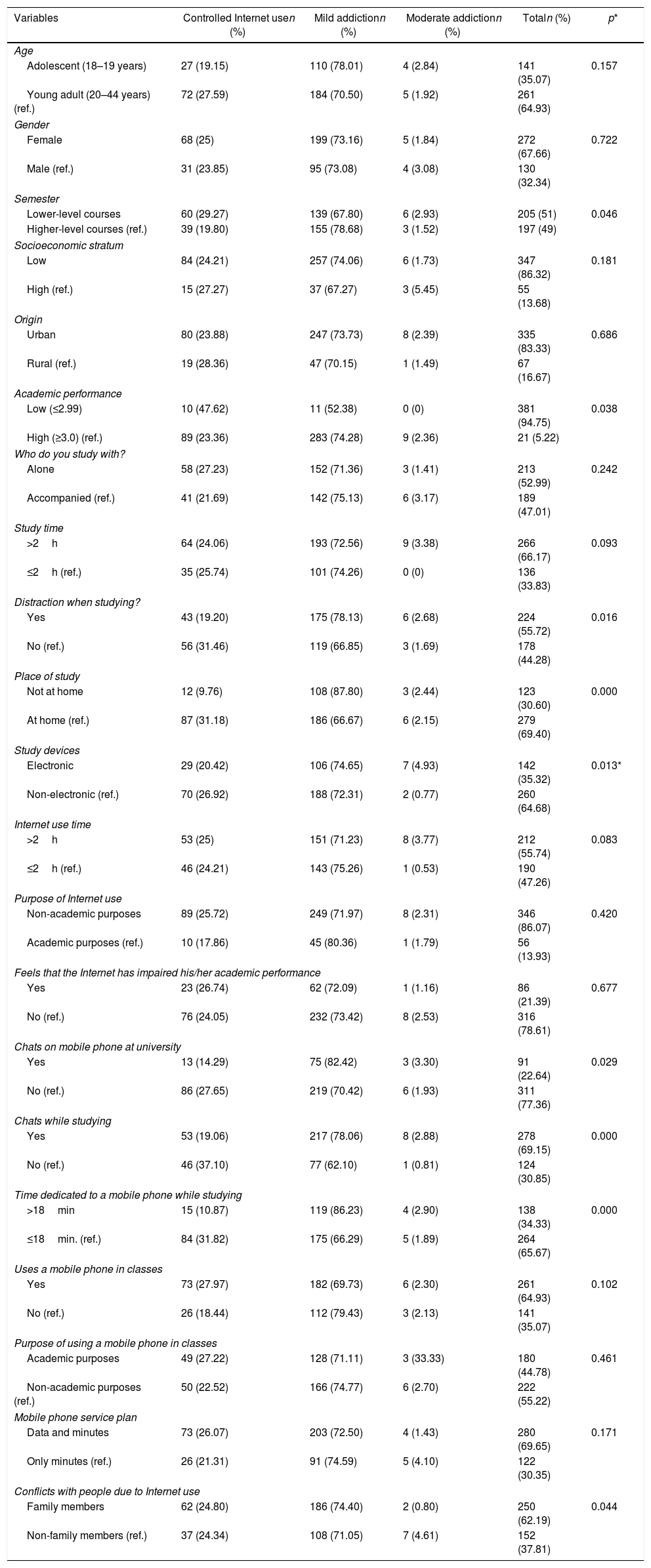

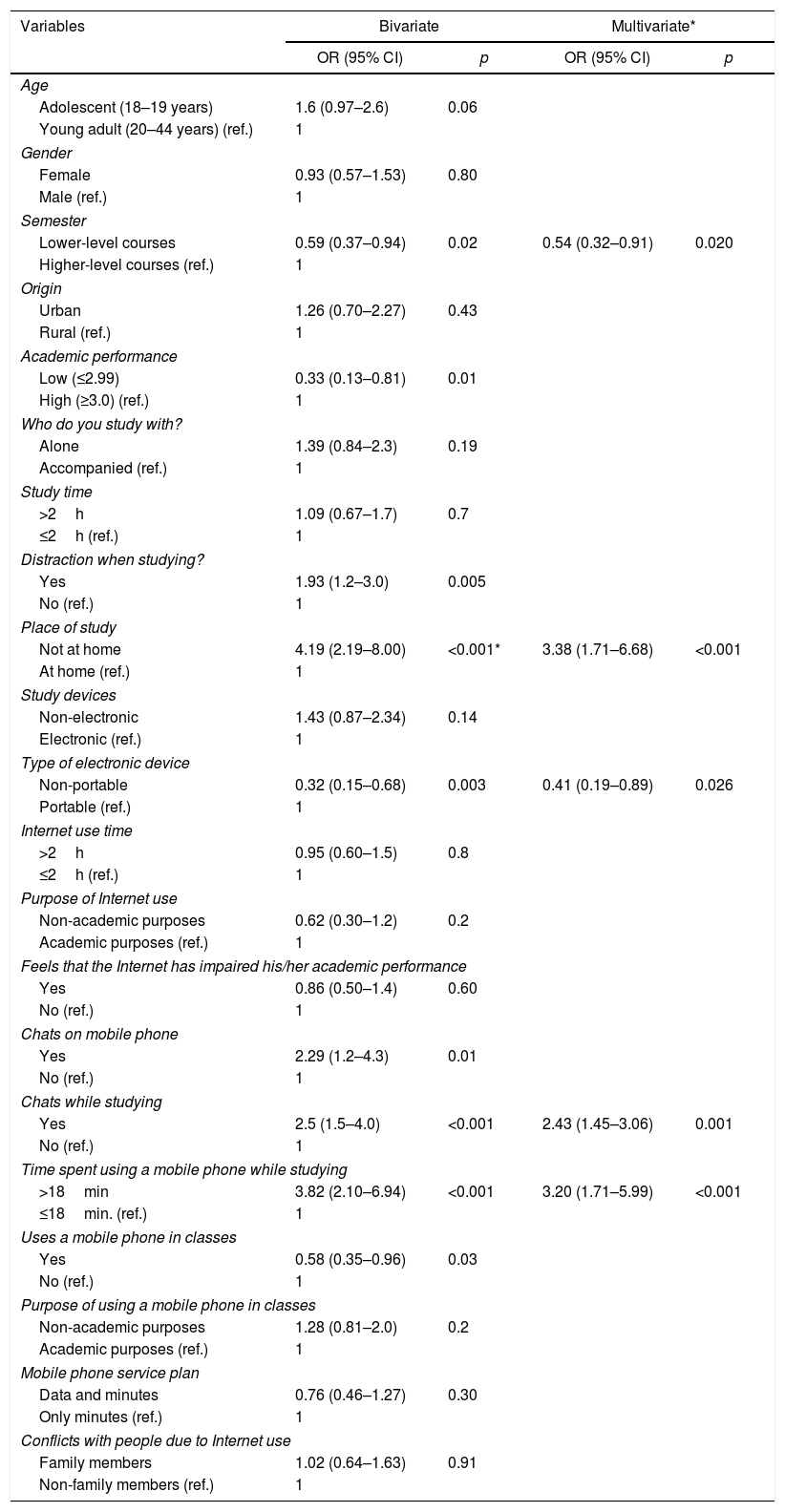

When relating IA categories to sociodemographic variables, academic performance and Internet use, statistically significant relationships were found with the semester variables, academic performance, distraction when studying, place of study, study device, chatting at university, chatting while studying and conflicts with people due to Internet use (p<0.05) (Table 2). Likewise, in the bivariate analysis a statistically significant relationship was found between IA and studying lower-level courses, poor academic performance, distraction when studying, studying in a place other than home, using a non-portable device to study, chatting on a mobile phone while studying, spending more than 18min answering a mobile phone while studying and using a mobile phone in classes (Table 3).

Relationship between sociodemographic variables related to academic performance and Internet use and Internet addiction in dental students at the Universidad de Cartagena, 2015.

| Variables | Controlled Internet usen (%) | Mild addictionn (%) | Moderate addictionn (%) | Totaln (%) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| Adolescent (18–19 years) | 27 (19.15) | 110 (78.01) | 4 (2.84) | 141 (35.07) | 0.157 |

| Young adult (20–44 years) (ref.) | 72 (27.59) | 184 (70.50) | 5 (1.92) | 261 (64.93) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 68 (25) | 199 (73.16) | 5 (1.84) | 272 (67.66) | 0.722 |

| Male (ref.) | 31 (23.85) | 95 (73.08) | 4 (3.08) | 130 (32.34) | |

| Semester | |||||

| Lower-level courses | 60 (29.27) | 139 (67.80) | 6 (2.93) | 205 (51) | 0.046 |

| Higher-level courses (ref.) | 39 (19.80) | 155 (78.68) | 3 (1.52) | 197 (49) | |

| Socioeconomic stratum | |||||

| Low | 84 (24.21) | 257 (74.06) | 6 (1.73) | 347 (86.32) | 0.181 |

| High (ref.) | 15 (27.27) | 37 (67.27) | 3 (5.45) | 55 (13.68) | |

| Origin | |||||

| Urban | 80 (23.88) | 247 (73.73) | 8 (2.39) | 335 (83.33) | 0.686 |

| Rural (ref.) | 19 (28.36) | 47 (70.15) | 1 (1.49) | 67 (16.67) | |

| Academic performance | |||||

| Low (≤2.99) | 10 (47.62) | 11 (52.38) | 0 (0) | 381 (94.75) | 0.038 |

| High (≥3.0) (ref.) | 89 (23.36) | 283 (74.28) | 9 (2.36) | 21 (5.22) | |

| Who do you study with? | |||||

| Alone | 58 (27.23) | 152 (71.36) | 3 (1.41) | 213 (52.99) | 0.242 |

| Accompanied (ref.) | 41 (21.69) | 142 (75.13) | 6 (3.17) | 189 (47.01) | |

| Study time | |||||

| >2h | 64 (24.06) | 193 (72.56) | 9 (3.38) | 266 (66.17) | 0.093 |

| ≤2h (ref.) | 35 (25.74) | 101 (74.26) | 0 (0) | 136 (33.83) | |

| Distraction when studying? | |||||

| Yes | 43 (19.20) | 175 (78.13) | 6 (2.68) | 224 (55.72) | 0.016 |

| No (ref.) | 56 (31.46) | 119 (66.85) | 3 (1.69) | 178 (44.28) | |

| Place of study | |||||

| Not at home | 12 (9.76) | 108 (87.80) | 3 (2.44) | 123 (30.60) | 0.000 |

| At home (ref.) | 87 (31.18) | 186 (66.67) | 6 (2.15) | 279 (69.40) | |

| Study devices | |||||

| Electronic | 29 (20.42) | 106 (74.65) | 7 (4.93) | 142 (35.32) | 0.013* |

| Non-electronic (ref.) | 70 (26.92) | 188 (72.31) | 2 (0.77) | 260 (64.68) | |

| Internet use time | |||||

| >2h | 53 (25) | 151 (71.23) | 8 (3.77) | 212 (55.74) | 0.083 |

| ≤2h (ref.) | 46 (24.21) | 143 (75.26) | 1 (0.53) | 190 (47.26) | |

| Purpose of Internet use | |||||

| Non-academic purposes | 89 (25.72) | 249 (71.97) | 8 (2.31) | 346 (86.07) | 0.420 |

| Academic purposes (ref.) | 10 (17.86) | 45 (80.36) | 1 (1.79) | 56 (13.93) | |

| Feels that the Internet has impaired his/her academic performance | |||||

| Yes | 23 (26.74) | 62 (72.09) | 1 (1.16) | 86 (21.39) | 0.677 |

| No (ref.) | 76 (24.05) | 232 (73.42) | 8 (2.53) | 316 (78.61) | |

| Chats on mobile phone at university | |||||

| Yes | 13 (14.29) | 75 (82.42) | 3 (3.30) | 91 (22.64) | 0.029 |

| No (ref.) | 86 (27.65) | 219 (70.42) | 6 (1.93) | 311 (77.36) | |

| Chats while studying | |||||

| Yes | 53 (19.06) | 217 (78.06) | 8 (2.88) | 278 (69.15) | 0.000 |

| No (ref.) | 46 (37.10) | 77 (62.10) | 1 (0.81) | 124 (30.85) | |

| Time dedicated to a mobile phone while studying | |||||

| >18min | 15 (10.87) | 119 (86.23) | 4 (2.90) | 138 (34.33) | 0.000 |

| ≤18min. (ref.) | 84 (31.82) | 175 (66.29) | 5 (1.89) | 264 (65.67) | |

| Uses a mobile phone in classes | |||||

| Yes | 73 (27.97) | 182 (69.73) | 6 (2.30) | 261 (64.93) | 0.102 |

| No (ref.) | 26 (18.44) | 112 (79.43) | 3 (2.13) | 141 (35.07) | |

| Purpose of using a mobile phone in classes | |||||

| Academic purposes | 49 (27.22) | 128 (71.11) | 3 (33.33) | 180 (44.78) | 0.461 |

| Non-academic purposes (ref.) | 50 (22.52) | 166 (74.77) | 6 (2.70) | 222 (55.22) | |

| Mobile phone service plan | |||||

| Data and minutes | 73 (26.07) | 203 (72.50) | 4 (1.43) | 280 (69.65) | 0.171 |

| Only minutes (ref.) | 26 (21.31) | 91 (74.59) | 5 (4.10) | 122 (30.35) | |

| Conflicts with people due to Internet use | |||||

| Family members | 62 (24.80) | 186 (74.40) | 2 (0.80) | 250 (62.19) | 0.044 |

| Non-family members (ref.) | 37 (24.34) | 108 (71.05) | 7 (4.61) | 152 (37.81) | |

Bivariate and multivariate analysis of the association between Internet addiction and academic performance and the variables associated with Internet use among dental students at the Universidad de Cartagena, 2015.

| Variables | Bivariate | Multivariate* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age | ||||

| Adolescent (18–19 years) | 1.6 (0.97–2.6) | 0.06 | ||

| Young adult (20–44 years) (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 0.93 (0.57–1.53) | 0.80 | ||

| Male (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Semester | ||||

| Lower-level courses | 0.59 (0.37–0.94) | 0.02 | 0.54 (0.32–0.91) | 0.020 |

| Higher-level courses (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Origin | ||||

| Urban | 1.26 (0.70–2.27) | 0.43 | ||

| Rural (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Academic performance | ||||

| Low (≤2.99) | 0.33 (0.13–0.81) | 0.01 | ||

| High (≥3.0) (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Who do you study with? | ||||

| Alone | 1.39 (0.84–2.3) | 0.19 | ||

| Accompanied (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Study time | ||||

| >2h | 1.09 (0.67–1.7) | 0.7 | ||

| ≤2h (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Distraction when studying? | ||||

| Yes | 1.93 (1.2–3.0) | 0.005 | ||

| No (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Place of study | ||||

| Not at home | 4.19 (2.19–8.00) | <0.001* | 3.38 (1.71–6.68) | <0.001 |

| At home (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Study devices | ||||

| Non-electronic | 1.43 (0.87–2.34) | 0.14 | ||

| Electronic (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Type of electronic device | ||||

| Non-portable | 0.32 (0.15–0.68) | 0.003 | 0.41 (0.19–0.89) | 0.026 |

| Portable (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Internet use time | ||||

| >2h | 0.95 (0.60–1.5) | 0.8 | ||

| ≤2h (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Purpose of Internet use | ||||

| Non-academic purposes | 0.62 (0.30–1.2) | 0.2 | ||

| Academic purposes (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Feels that the Internet has impaired his/her academic performance | ||||

| Yes | 0.86 (0.50–1.4) | 0.60 | ||

| No (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Chats on mobile phone | ||||

| Yes | 2.29 (1.2–4.3) | 0.01 | ||

| No (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Chats while studying | ||||

| Yes | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) | <0.001 | 2.43 (1.45–3.06) | 0.001 |

| No (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Time spent using a mobile phone while studying | ||||

| >18min | 3.82 (2.10–6.94) | <0.001 | 3.20 (1.71–5.99) | <0.001 |

| ≤18min. (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Uses a mobile phone in classes | ||||

| Yes | 0.58 (0.35–0.96) | 0.03 | ||

| No (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Purpose of using a mobile phone in classes | ||||

| Non-academic purposes | 1.28 (0.81–2.0) | 0.2 | ||

| Academic purposes (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Mobile phone service plan | ||||

| Data and minutes | 0.76 (0.46–1.27) | 0.30 | ||

| Only minutes (ref.) | 1 | |||

| Conflicts with people due to Internet use | ||||

| Family members | 1.02 (0.64–1.63) | 0.91 | ||

| Non-family members (ref.) | 1 | |||

In the multivariate analysis, the model which best explains the presence of IA in dental students in relation to their academic performance was obtained with the following factors: studying lower-level courses (non-clinical cycles, OR=0.54; 95% CI, 0.32–0.91); studying away from home (OR=3.38; 95% CI, 1.71–6.68); using a non-portable device to study (OR=0.41; 95% CI, 0.19–0.89); chatting on a mobile phone (OR=2.43; 95% CI, 1.45–3.06); and spending 18min or more answering a mobile phone while studying (OR=3.20; 95% CI, 1.71–5.99) (Table 3).

Psychometric properties of the Internet addiction testThe exploratory factor analysis (EFA) proposed two domains composed of items 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 14, 16, 17 and 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 18, 19, 20, respectively. These factors explained 30.3% of the total variance. The adjustment indicators obtained in the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for this structure were: χ2p<0.01; RMSEA=0.08; CFI=0.78 and TLI=0.75.

General internal consistency was 0.83. For domain 1, internal consistency was 0.73, while for domain 2 it was 0.81.

DiscussionTaking into account the rapid changes that take place in our society regarding Internet use, which is reflected not only in positive aspects, such as greater availability of study and reference material, employment opportunities, education and training, its uncontrolled use can have a negative impact on adolescents and young adults, such as dependency and risky exposure to social problems such as child pornography,33 grooming34 and eating disorders.35 This study is relevant as it sheds light on Internet use among dental students, a population which is also vulnerable as it is made up of young people. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study carried out in dental students relating IA to academic performance in Colombia, and contributes to both variables with scientific inputs for improved study and analysis. Studies were found regarding medical students,21 40.4% of whom reported impaired academic performance due to IA, while in this study no association was found following the multivariate analysis.

Despite the fact that such an association was not identified, it was found that more than half of dental students (75.4%) have IA, and the vast majority claim that the Internet is not used for academic purposes. These prevalences are higher than those reported in dental students in Asia by Gedam et al.6 (2.3%) and Younes et al.36 among medical, dental and chemistry students at Saint Joseph's University (16.8%), even when these figures are compared with the presence of mild addiction for this study. However, a study by Tsimtsiou et al.37 of medical students in Greece reported prevalences of the different levels of severity of addiction (mild, 24.5%; moderate, 5.4%; severe, 0.2%), with behaviour similar to the figures reported in this study (63.2% of mild addiction, 12.2% of moderate addiction and no severe addiction), also with a higher prevalence of mild addiction. It is likely that the prevalences of IA found in this study are due to the vast majority of students being far from their place of origin, which exposes them to making decisions about their own behaviours in the absence of parental figures supervising their behaviour, such as appropriate use of the Internet. Therefore, studying away from home is one of the variables associated with the risk of IA in dental students. This is consistent with another study, but in medical students, which found that visiting Internet cafés is an addiction risk factor.38 Away from their parents’ home, there is no-one to monitor their reason for using the Internet or length of time using the Internet, which predisposes to IA. Use of the Internet for non-academic purposes is increasing among students, which is why there is an immediate need for strict familial and institutional supervision, and away from their place of residence they are more predisposed to Internet use for this purpose.21 It should be taken into account that improved access to the Internet and the greater availability of high-tech equipment, such as high-end mobile phones, have facilitated connection to the Internet and, therefore, its greater use, which could explain the figures reported in this study on mild addiction, that it is not really a mild addiction as the Young test describes, but rather frequent use. These data should be interpreted very carefully and require a clinical check to assess other variables which could influence the emergence of addictive behaviour, including family problems and the student's personality.10–16 In any case, the Young test may be very useful in the clinical evaluation and screening, as it is the instrument with the greatest number of adaptations to different languages.24

Another of the variables associated with the presence of IA in dental students, but a protective variable, is studying lower-level courses (non-clinical cycles) and studying with non-portable devices. The ease of having devices wherever you are and the use of Wi-Fi networks which are increasingly more accessible in different areas and establishments, as well as in higher education institutions, enable greater Internet use. Furthermore, smartphones and tablets, computers “at your fingertips”, are portable devices which predispose to greater Internet use which in turn increases the likelihood of IA.39 In addition, during the lower-level courses, these students have a larger theoretical academic load and acquisition of manual skills, which means they need to dedicate more time to acquiring these skills and a more significant source of stress is created than for students studying higher-level courses. This could limit the time spent using electronic devices, making this population less susceptible to IA.40

Another of the variables that in the multivariate model explains the presence of IA in dental students, but this time a risk variable, is spending more than 18min answering or using a mobile phone while studying, doing activities such as chatting, which is consistent with the findings of Nath et al.21: excessive Internet use impaired the academic performance of medical students.21 Staying connected to the Internet or on line for a long time does not allow routine activities that are important to the individual to be performed, such as sleeping the necessary number of hours of sleep.38 It affects social and family relationships and is detrimental to academic performance,11 which promotes the onset of these types of addictions. Furthermore, mobile devices contribute to the acquisition of these types of unhealthy habits due to their ease of use and availability.

Dental students have risk factors which promote the onset of IA and may compromise their academic performance. Despite the fact that in this study no relationship was found between academic performance and IA, it is vitally important to bear in mind that the majority of the population who participated in the study was classified as mildly addicted, and that if action is not taken in a timely manner, they may be predisposed to suffering from moderate or severe addiction problems, with the possibility of outcomes with a greater impact. This demonstrates the usefulness of the Young test for screening, as happened in this study, as it makes it possible to detect a possible risk of IA in these populations at an early stage, taking into account the psychometric performance that is reported when performing the CFA and the EFA of the test both in Spanish24,25 and in other languages,41–44 coinciding with the psychometric performance of the scale obtained in this study.

It should be stressed to students and their parents through awareness campaigns that there is the possibility of them becoming addicted to the Internet, so that interventions and restrictions can be implemented in individuals and families, but the University, responsible for academic and humanistic training, should look out for the well-being of its students during their academic stay through awareness-raising sessions on the proper use of this tool.

It is important to make the caveat, with regard to the limitations found when conducting this study, that not many studies on IA and their consequences in dental students are available. Self-application of the scale to measure IA requires precise self-perception and the intention of being truthful. Furthermore, when this addiction is analysed in the few studies found with regard to the related factors, depression is one of the variables most associated with IA in medical and dental students. Although in this study the presence of depression or any other psychological disorder was not investigated, which could represent a weakness of the study, it is important to investigate this in future research and to incorporate clinical evaluations which enable the results of the Young test to be checked, taking into account the absence of a reference standard with regard to other instruments. Although the results obtained by the test are not an official clinical diagnosis, there are different perspectives in the literature with regard to the most extensive terms and criteria of excessive Internet use behaviours.45 Therefore, our findings are approximations that must be assessed in future studies.

ConclusionsAlthough an association between IA and poor academic performance was not found, variables which influence IA were found, such as studying lower-level courses, studying away from home, using a non-portable device to study, chatting and spending more than 18min answering a mobile phone while studying. Identifying these factors facilitates the clear design of interventions by higher education institutions that promote good use of the Internet in the interest of academic performance.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this research.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

FundingInternal resources.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank Yheila Figueroa Angulo, Iveth Orellano Badillo and Ana María Zapata for their collaboration in the study.

Please cite this article as: Díaz Cárdenas S, Arrieta Vergara K, Simancas-Pallares M. Adicción a internet y rendimiento académico de estudiantes de Odontología. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2019;48:198–207.