To implement clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the timely detection and diagnosis of eating disorders in adolescents and adults in the priority outpatient department of a public psychiatric hospital in Barranquilla, Colombia. Barriers to access to the implemented guidelines were identified.

MethodsFor the identification of evidence-based CPGs to be implemented, systematic searches were carried out in international databases of development agencies or compilers of clinical practice guidelines, and in databases that contained scientific literature on issues related to eating disorders.

ConclusionsThe two guidelines shortlisted for the final selection by consensus of a multidisciplinary team at the hospital were the “Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders” and the “Guía de práctica clínica sobre trastornos de la conducta alimentaria de Catalunya”, the latter being finally chosen by consensus. There are not yet CPGs implemented for health professionals in the priority outpatient department of Colombian hospitals for eating disorders.

Implementar una guía de práctica clínica para la detección oportuna y el diagnóstico de los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en adolescentes y adultos en los servicios de consulta prioritaria y consulta externa de un hospital mental público de Barranquilla, Colombia. Se identificaron barreras para el acceso a la guía implementada.

MétodosPara identificar guías de práctica clínica basadas en la evidencia que implementar, se hicieron búsquedas sistemáticas en bases de datos internacionales de organismos desarrolladores o compiladores de guías de práctica clínica y en bases de datos que recogieran literatura científica sobre temas relacionados con trastornos de la conducta alimentaria.

ConclusionesLas dos guías para realizar la selección final por consenso de un equipo multidisciplinario del hospital fueron: «Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders» y «Guía de práctica clínica sobre trastornos de la conducta alimentaria de Catalunya», que finalmente fue la elegida por consenso. No existe aún para los profesionales de la salud una guía de práctica clínica implementada en el servicio de consulta externa y prioritaria de los hospitales colombianos para los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria.

Eating disorders (ED) are a group of conditions related to an individual's altered body image and their abnormal eating behaviour.

Eating disorders have taken on great relevance in public health over the last few decades on account of their severity, complexity and the difficulty in establishing a diagnosis, due to their multi-dimensional nature, as well as a specific treatment. They are diseases of multifactorial aetiology, mainly affecting children, adolescents and young adults and involving genetic, biological, personality, family and sociocultural factors. Despite the methodological difficulties in the diagnosis, there has been a notable increase in the prevalence of eating disorders, particularly in developed or developing countries, whereas ED are practically non-existent in less developed countries. The increased prevalence is attributable to the increased incidence and duration and chronic nature of these clinical conditions.

According to the British National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical practice guidelines (CPG),1 the prevalences of unspecified feeding or eating disorders (UFED), bulimia nervosa (BN) and anorexia nervosa (AN) in females are 1%–3.3%, 0.5%–1.0% and 0.7%, respectively. The Systematic Review of Scientific Evidence (SRSE) (2006) reported prevalences in Eastern Europe and the United States of 0.7%–3% for UFED in the community, 1% for BN in females and 0.3% for AN in young females.1

Various studies published in the United States, Canada and Europe on the incidence of eating disorders show a five- to six-fold increase in the 1960–1970 period.2

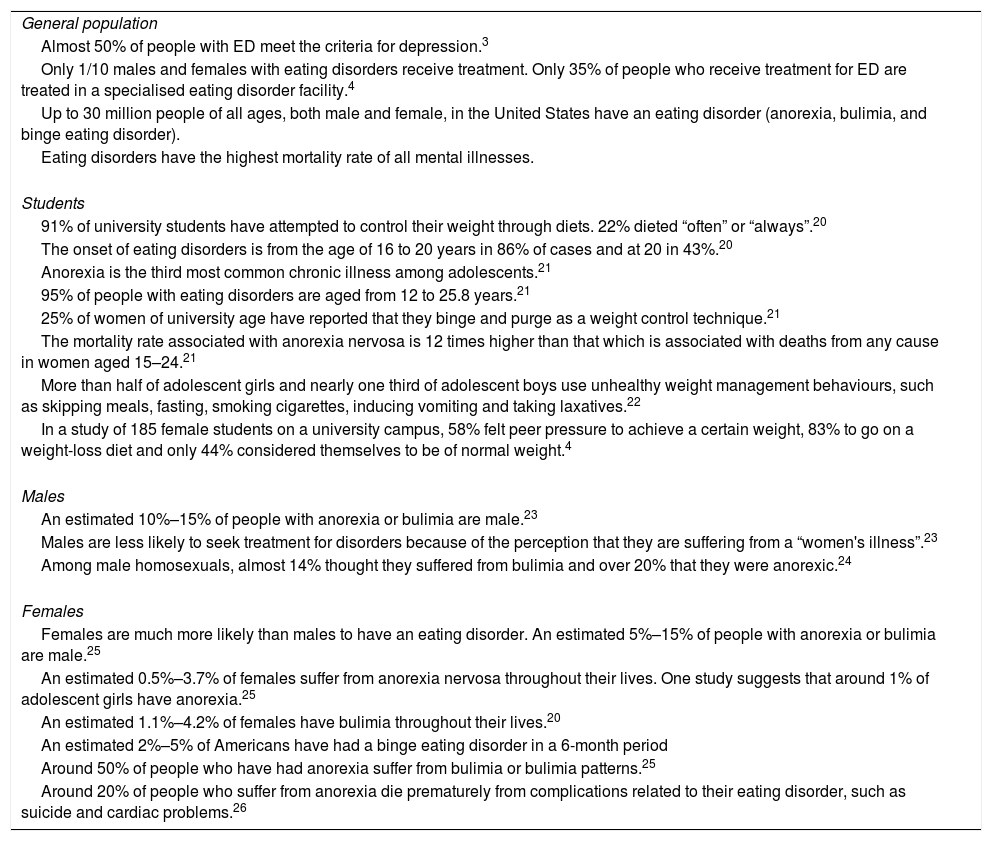

According to information published on the website of the United States National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders (ANAD), the following are the main figures for ED (Table 1):

- •

Almost 50% of people with ED meet the criteria for depression.3

- •

Only one in ten males and females with ED receive treatment. Only 35% of the people who receive treatment for ED are treated at a specialised eating disorder centre.4

- •

Anorexia is the third most common chronic illness among adolescents.18

- •

95% of people with ED are aged from 12 to 25.8 years.18

- •

25% of women of university age have reported bingeing and purging as a weight control technique.18

Eating disorder statistics in the United States according to ANAD.

| General population |

| Almost 50% of people with ED meet the criteria for depression.3 |

| Only 1/10 males and females with eating disorders receive treatment. Only 35% of people who receive treatment for ED are treated in a specialised eating disorder facility.4 |

| Up to 30 million people of all ages, both male and female, in the United States have an eating disorder (anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating disorder). |

| Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of all mental illnesses. |

| Students |

| 91% of university students have attempted to control their weight through diets. 22% dieted “often” or “always”.20 |

| The onset of eating disorders is from the age of 16 to 20 years in 86% of cases and at 20 in 43%.20 |

| Anorexia is the third most common chronic illness among adolescents.21 |

| 95% of people with eating disorders are aged from 12 to 25.8 years.21 |

| 25% of women of university age have reported that they binge and purge as a weight control technique.21 |

| The mortality rate associated with anorexia nervosa is 12 times higher than that which is associated with deaths from any cause in women aged 15–24.21 |

| More than half of adolescent girls and nearly one third of adolescent boys use unhealthy weight management behaviours, such as skipping meals, fasting, smoking cigarettes, inducing vomiting and taking laxatives.22 |

| In a study of 185 female students on a university campus, 58% felt peer pressure to achieve a certain weight, 83% to go on a weight-loss diet and only 44% considered themselves to be of normal weight.4 |

| Males |

| An estimated 10%–15% of people with anorexia or bulimia are male.23 |

| Males are less likely to seek treatment for disorders because of the perception that they are suffering from a “women's illness”.23 |

| Among male homosexuals, almost 14% thought they suffered from bulimia and over 20% that they were anorexic.24 |

| Females |

| Females are much more likely than males to have an eating disorder. An estimated 5%–15% of people with anorexia or bulimia are male.25 |

| An estimated 0.5%–3.7% of females suffer from anorexia nervosa throughout their lives. One study suggests that around 1% of adolescent girls have anorexia.25 |

| An estimated 1.1%–4.2% of females have bulimia throughout their lives.20 |

| An estimated 2%–5% of Americans have had a binge eating disorder in a 6-month period |

| Around 50% of people who have had anorexia suffer from bulimia or bulimia patterns.25 |

| Around 20% of people who suffer from anorexia die prematurely from complications related to their eating disorder, such as suicide and cardiac problems.26 |

Source: adapted from the American National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA).

In Colombia, “ED present frequently. Not many studies were found, but two carried out in students from Bucaramanga (2005)5 and medical students at Universidad Nacional (2012)6 estimated that 30% had symptoms. Of these, 1.7% corresponded to anorexia, 6% to bulimia and 28% to unspecified eating disorders”, according to the psychiatrist Pilar Arroyave in an interview with the ElEspectador7 newspaper, citing a study carried out by Ángel et al.8 in 2008 in a 2770-strong student population.

According to the 2015 National Mental Health Survey, very few community studies have been conducted in Colombia, and most of them were carried out on samples of school and university students in cities in different parts of the country to explore the prevalence, factors and risk behaviours. Among medical students, for example, there were associated factors such as the desire to lose more than 10% of their weight,9 high perceived stress and problematic alcohol consumption.6 Among the school-age population, there was a family history of eating disorders, obesity, personal and family dissatisfaction with their shape and body weight, and criticism and negative comments on weight and shape.10 In addition, 77% of the respondents said they were “terrified at the thought of gaining weight”, 33% felt guilty after eating, 16% said that food controlled their life and 8% induced vomiting after eating.11

With technical-scientific criteria, in 2013 the Ministry of Health and Social Protection (Minsalud) and the Administrative Department of Science and Technology and Innovation (Colciencias) jointly published 25 evidence-based CPG for the following reasons12,13:

- •

Variability in healthcare professionals’ clinical practice.

- •

CPG provide a solid base for updating healthcare professionals’ knowledge.

- •

They help healthcare professionals to provide patients with the best possible care.

- •

CPG improve the effectiveness of clinical care and the quality of healthcare (processes).

- •

They are an important input for improving the quality of patient care.

The implementation of the CPG for Colombia is considered a novel experience that poses new challenges to the Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud (SGSSS) [General System of Social Security in Health] and its different stakeholders. Putting CPG recommendations into practice in institutions providing health services involves designing, planning and executing strategies for promotion, adoption, dissemination and follow-up in the different service providers in Colombia's different cultural and social contexts.12,14

For the implementation of the CPG, the healthcare providers, and therefore the Hospital ESE Cari Neurociencias, must take responsibility for the following15:

- •

Designing and executing the local CPG implementation plan.

- •

Implementing the CPG according to the established plan.

- •

Linking the implementation of the CPG to institutional authorisation and accreditation processes.

- •

Reviewing and adapting the healthcare providers’ information systems according to the standards and implementation indicators proposed in the CPG.

However, despite the existence of a Mental Health Law enacted in accordance with the World Health Organisation's principles for primary healthcare, the significant public health problem posed by ED and the availability of 25 evidence-based CPG, our healthcare professionals still lack a guideline developed for the Colombian population and far less a CPG implemented in the Hospital Mental ESE Cari Neurociencias outpatient and priority consultation department in Barranquilla.

Our objective is therefore to implement a set of CPG for the early detection and diagnosis of eating disorders in adolescents and adults in the priority consultation and outpatient departments at the Hospital Mental ESE Cari Neurociencias in the city of Barranquilla.

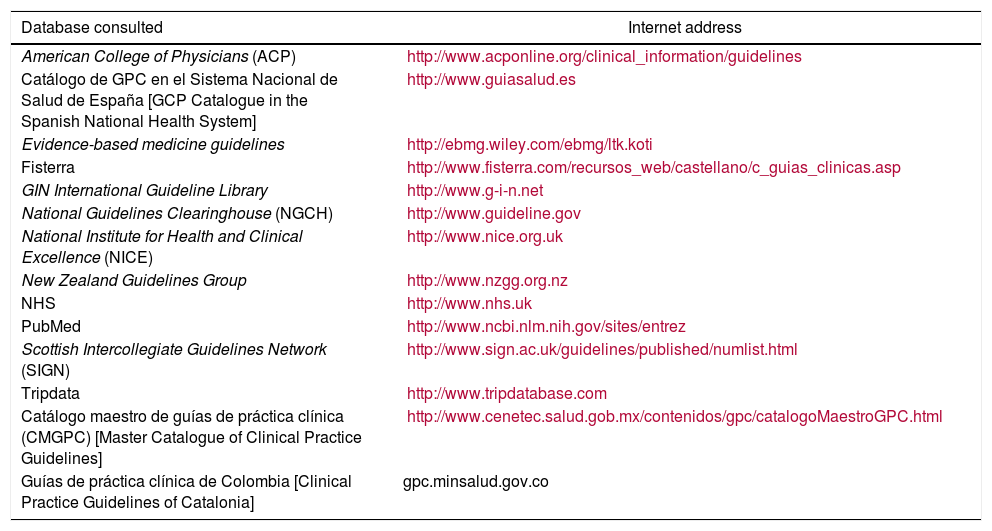

MethodsThe aim of this research is to draw up an implementation plan for a CPG for the management of ED at the Hospital ESE Cari Neurociencias in Barranquilla according to the methodology of the Ministry of Health's evidence-based CPG implementation manual. The data collection instrument used in this research was a questionnaire with open and closed questions. Information was recorded about academic training, time worked at the ESE Cari Neurociencias and specific professional experience, as well as management experience in their professional life and preferences regarding CPG in ED. This research was classified as free of risk and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as retrospective documentary research techniques and methods were used and it did not involve any intervention or intentional modification, being based on the conduct of interviews and empowerment activities of the interviewees. The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Universidad del Norte and the Hospital Mental ESE Cari in Barranquilla. Colombia has no CPG for ED developed by the Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social [Ministry of Health and Social Protection]. Therefore, the first step in the implementation of guidelines was to choose one. In order to identify potential evidence-based CPG, systematic searches were run in international databases of organisations which developed or compiled CPG and in databases that collected scientific literature on topics related to eating disorders (Table 2). To search for local guidelines, psychiatrists from the city of Barranquilla (who had a working relationship with the Hospital ESE Cari Neurociencias and the academy) were asked to report on the existence of evidence-based CPG according to their use and knowledge.

Databases consulted.

| Database consulted | Internet address |

|---|---|

| American College of Physicians (ACP) | http://www.acponline.org/clinical_information/guidelines |

| Catálogo de GPC en el Sistema Nacional de Salud de España [GCP Catalogue in the Spanish National Health System] | http://www.guiasalud.es |

| Evidence-based medicine guidelines | http://ebmg.wiley.com/ebmg/ltk.koti |

| Fisterra | http://www.fisterra.com/recursos_web/castellano/c_guias_clinicas.asp |

| GIN International Guideline Library | http://www.g-i-n.net |

| National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGCH) | http://www.guideline.gov |

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) | http://www.nice.org.uk |

| New Zealand Guidelines Group | http://www.nzgg.org.nz |

| NHS | http://www.nhs.uk |

| PubMed | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez |

| Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) | http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/published/numlist.html |

| Tripdata | http://www.tripdatabase.com |

| Catálogo maestro de guías de práctica clínica (CMGPC) [Master Catalogue of Clinical Practice Guidelines] | http://www.cenetec.salud.gob.mx/contenidos/gpc/catalogoMaestroGPC.html |

| Guías de práctica clínica de Colombia [Clinical Practice Guidelines of Catalonia] | gpc.minsalud.gov.co |

Source: own data.

The following English search structure was used: (“Guidelines as Topic” [Mesh]) OR (“Practice Guidelines as Topic” [Mesh]) OR (“Guideline” [Publication Type]) OR (“Practice Guideline” [Publication Type]) OR (guideline [Title/Abstract]) AND (adapt*[tw] OR tailor*[tw]). Se adaptaron los términos de uso más frecuente a la búsqueda en español. La búsqueda se filtró para incluir únicamente guías de práctica clínica.

The following inclusion criteria were used for the CPG:

- •

Evidence-based guidelines.

- •

Guidelines developed through an expert group process.

- •

Guidelines that establish recommendations.

- •

Guidelines whose scope and objectives are related to anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder.

The CPG to be implemented was chosen by the consensus of an interdisciplinary team of researchers based on the responses provided in the survey (Annex 1): a medical psychiatrist, an MSc in Clinical Epidemiology, an undergraduate and post-graduate lecturer in the Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health at the Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá, where he works and participates in research activities, an active member of the International Academy for Eating Disorders, the Eating Disorders Research Society, the Asociación Colombiana de Psiquiatría [Colombian Association of Psychiatry] and the Asociación Colombiana de Terapia del Comportamiento [Colombian Association of Behavioural Therapy], and a multidisciplinary team working at the Hospital Mental ESE Cari (psychiatrists, epidemiologists, nurses and clinical psychologists).

ResultsThe two sets of guidelines ultimately found for the final consensus-based selection were the “Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders” and the “Guía de práctica clínica sobre trastornos de la conducta alimentaria” [Clinical Practice Guidelines for Eating Disorders].

The most relevant clinical features of these CPG are as follows:

- a)

“Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders” by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. The latest edition dates from 2014; it uses the diagnostic manual based on the DSM-5 and the ICD-10; it was developed in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia's best clinical practices; the scientific evidence for the treatments of AN, BN, binge eating disorder (BED), other specified and unspecified eating disorders, and avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) was obtained from reviews of the CPG prior to the current one (2009) and updated with a systematic review (2008–2013); a multidisciplinary working group produced the draft CPG, which then underwent expert, community and stakeholder consultation, during which process additional evidence was obtained; the guide addresses the most common ED but not grazing, unspecified feeding or eating disorders (UFED), ARFID or rumination disorder.

- b)

“Guía de práctica clínica sobre trastornos de la conducta alimentaria” [Clinical Practice Guideline for Eating Disorders]. It is written in Spanish; it was funded through the agreement signed by Instituto de Salud Carlos III [Carlos III Health Institute], an autonomous body of the Spanish Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs, and the Agència d’Avaluació de Tecnologia i Recerca Mèdiques de Cataluña [Health Evaluation and Quality Agency of Catalonia], within the collaboration framework provided for in the Quality Plan for the National Health System; diagnosis is based on DSM-4 and ICD-10; this edition was published in January 2009. Therefore, and as is pointed out in the actual CPG, “This CPG was published over five years ago and is due for an update. The recommendations contained in it must be taken with caution, considering that its continued validity is pending evaluation”; this CPG recommends the use of questionnaires adapted for and validated in the Spanish population for the identification of cases (screening) of ED.

Once the aforementioned methodology question had been addressed, the “Clinical Practice Guidelines for Eating Disorders” of Catalonia was chosen by consensus, as over 85% of the respondents considered it inappropriate to adopt a CPG for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with eating disorders in English (Annex 1, question 5).

Identification of barriersThe process of identifying barriers to accessing the guide was addressed after the CPG had been institutionally implemented. The Delphi technique was used, and a questionnaire was sent out in the first phase with tested and validated questions for the participants to rate their degree of agreement with each statement in the questionnaire.

The group of experts then identified the following barriers to the implementation of the Catalan ED CPG:

- •

Difficulties in accessing the ESE Cari Mental. The ESE Cari Mental is the only public hospital in the region. It is located in Barranquilla, hence it could be difficult for the user population to travel there for specialised care.

- •

Poor understanding of clinical texts written in English, which ultimately determined the choice of the Catalan guideline.

- •

Scant experience in the use of CPG among the scientific community. According to the Colombian Ministry of Health, the main barriers for doctors to use and adhere to the guidelines are lack of knowledge of the existence of guidelines, lack of familiarity or agreement with them, a mistrust of guidelines, a lack of expectations about outcomes, the inertia of traditional practice and other external barriers.16 This was made evident in the survey, as over 80% of the employees surveyed stated that they did not know of any ED CPG.

- •

Lack of healthcare professionals specialised in eating disorders. In the Atlántico Department, and even more so in Barranquilla, there is a shortage of professionals with appropriate training in the diagnosis, psychotherapy and psychopharmacotherapy proposed in the ED CPG, and those who are available are not distributed equally among the user population. Even for this research, the expert collaborator is from the city of Bogotá. This lack of expertise among medical psychiatrists, psychiatry residents, nurses and others would be a barrier to following the recommendations of this CPG.

- •

Social stigma and discrimination against people with eating disorders and ignorance of their mental health rights.17 As a consequence, the patient and anyone close to them may indefinitely delay or postpone specialised clinical care, which aggravates the situation.

The demand for health services always seems to surpass the available resources. The same is true in all countries worldwide, even those classified as high-income. For the Colombian social security system to be viable, it is essential to ensure the collection and proper administration of financial resources that support investment in and operation of healthcare structures and processes. However, while this is necessary, it will not suffice. Finding the point of equilibrium in the system requires not only a sufficient, timely and appropriate contribution and flow of resources, but also that such expenditure and investment be reasonable, efficient and proportionate to the available resources.13,18

That said, the available resources are never sufficient to meet all the healthcare demands and expectations of the entire population in any country, even using all the viable management alternatives available. CPG thus become very useful instruments in guaranteeing quality of care and the professional self-regulation of healthcare personnel. To the extent that they reduce undesirable variability in the treatment of specific clinical conditions and promote the use of healthcare strategies and interventions of scientific evidence-based effectiveness and safety, not only do they improve the quality of care and eventual health outcomes, they must also make a significant contribution to reducing healthcare spending and considerably improving the system's productive efficiency.13,18

CPG are also important in reducing heterogeneity in clinical practice and as support to decision-makers, insurers and providers. CPG provide support when patient preferences and values are integrated with professional criteria and available resources in an effort to obtain the best overall patient outcomes.19

Therefore, the implementation of CPG in the clinical-administrative context of the ESE Cari Mental (including the other territorial organisations) is a decision that will streamline human and administrative resources, which will not always be sufficient.13,18

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors greatly appreciate the scientific support received from the Universidad del Norte Faculty of Medicine and its psychiatry programme. They would also like to thank the administrative and clinical staff of the Hospital ESE Cari Neurociencias in the city of Barranquilla.

Edgar Navarro Lechuga, Master in Epidemiology, coordinator of the Masters Degree Course in Epidemiology at Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla, Colombia, and Maritza Rodríguez Guarín, Master in Epidemiology, lecturer in the Psychiatry programme at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá.

Please cite this article as: Pertuz-Cortes C, Navarro-Jiménez E, Laborde-Cárdenas C, Gómez-Méndez P, Lasprilla-Fawcett S. Implementación de una guía de práctica clínica para la detección oportuna y el diagnóstico de trastornos de la conducta alimentaria en adolescentes y adultos en el servicio de consulta externa y prioritaria de un hospital mental público de Colombia. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2020;49:101–107.