Suicidal ideation and attempts are strongly predictive of suicide deaths. Furthermore, suicide attempts exert a financial burden of millions of dollars on society.

ObjectiveTo establish the factors associated with more than one suicide attempt in the Colombian population that was reported in 2016.

MethodsA cross-sectional study of 18,763 reports entered in the database of the National Public Health Surveillance of the National Institute of Health of Colombia during 2016 was performed.

Results11,738 (62.6%) of the total number of reports were female, the mean age was 25.0 (95% CI, 24.9–25.2) years, 46% of all cases were individuals between 10- and 20-years-old; 5734 (30.6%) reported 2 or more suicide attempts and the prevalence of a mental disorder and persistent suicidal ideation were 48.5% and 16.4%, respectively. The factor most strongly associated with more than one suicide attempt, after adjusting for logistic regression, was persistent suicide ideation with crude OR=5.5 (95% CI, 5.0–5.9), and ORa=4.0 (95% CI, 3.6–4.3).

ConclusionsPatients with persistent suicidal ideation were 4 times more likely to have 2 or more suicide attempts. Other factors such as the use of a sharp weapon as a mechanism to perform the attempt and the history of bipolar affective disorder and/or depression were also associated with more than one suicide attempt.

La ideación suicida y los intentos son muy predictivos de muerte por suicidio. Además, los intentos de suicidio causan a la sociedad una carga financiera de millones de dólares.

ObjetivoEstablecer los factores asociados con más de un intento de suicidio registrado en 2016 en la población colombiana.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio trasversal de 18,763 reportes consignados en la base de datos del Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia en Salud Pública del Instituto Nacional de Salud de Colombia durante 2016.

ResultadosDel total de reportes, 11,738 (62.6%) corresponden al sexo femenino; la media de edad fue 25.0 (IC95%, 24.9-25.2) años; el 46% de todos los casos corresponden a personas entre 10 y 20 años. Refirieron 2 o más intentos de suicidio 5,734 (30.6%). Las prevalencias de alguna enfermedad mental y de ideación suicida persistente fueron del 48.5 y el 16.4% respectivamente. Tras realizar el ajuste mediante regresión logística, el factor más asociado con más de 1 intento suicida, fue la ideación suicida persistente: OR bruta=5.5 (IC95%, 5.0-5.9) y ORa=4.0 (IC95%, 3.6-4.3).

ConclusionesLos pacientes con ideación suicida persistente tienen una probabilidad 4 veces mayor de hacer 2 o más intentos suicidas. Otros factores, como el uso de arma cortopunzante como mecanismo para ejecutar el intento y el antecedente de trastorno afectivo bipolar y/o depresión, también se asociaron con más de 1 intento de suicidio.

According to figures from the World Health Organisation (WHO), 800,000 people commit suicide each year and an even greater number attempt suicide; it is presumed that for every suicide death there are 20 attempts.1 In 2015, a total annual age-standardised suicide rate of 10.7/100,000 population was calculated. It was the second leading cause of death in the 15–29 year-olds age group worldwide. Although more than 78% of suicides occurred in low- and middle-income countries, it is a global phenomenon that affects all regions and may occur at any age, thus constituting a serious public health problem.1 In Colombia, in 2013 the suicide rate was 4.4/100,000, and it seems to have remained stable in recent years.2

Attempted suicide is defined as non-fatal, self-directed behaviour, with the intention of dying as a result, which is potentially harmful even if it does not result in injury, in order to distinguish between self-inflicted injury with non-suicidal intent and suicide, defined as death caused by harmful behaviour directed against oneself with the intention of dying.3 Such self-inflicted injuries in Latin America represent 1.3% of all disability-adjusted life years (DALY).4

The prevalence of attempted suicide is difficult to establish, as it is not monitored in the same way in all countries, and reliable information is not available in many of them. A prevalence of 3%–5% in over-15s has been estimated worldwide, while in Colombia the prevalence was 2.57% (1.9% of males and 3.3% of females) of over-18s according to the 2015 National Mental Health Survey.5 In January 2016, the National Institute of Health began surveillance of attempted suicide as an event of public health interest.

Suicidal ideation and attempted suicide are highly predictive of death by suicide. Furthermore, attempted suicide may have negative consequences such as injury, hospitalisation and loss of liberty, and it imposes a financial burden of millions of dollars on society.6 A reported 90% of people who die by suicide have an underlying mental disorder. However, there is evidence that over 98% of people with mental disorders do not die by suicide.3

Some mental disorders involve a greater risk of suicide than others; for example, in developed countries, the disorders that most predict a suicide attempt are bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and major depression, while in developing countries it is post-traumatic stress disorder, conduct disorder and drug abuse/dependence.3

Millions of Colombians currently suffer from mental health problems such as depression, anxiety and psychosis, symptoms which are common to multiple mental illnesses, including major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Adolescents and women of all ages are most affected by this type of disorder.5 The association between suicidal ideation, attempted suicide and mental illness has been extensively studied worldwide. However, in the Colombian population there is still a lack of adequate documentation of the factors associated with more than one suicide attempt in a lifetime. Having this information would help us to predict the likelihood of a further attempt, thereby improving prevention and timely treatment. The aim of this study was to establish the factors associated with more than one suicide attempt registered in 2016 in the Colombian population.

MethodsIn 2016, a total of 18,903 attempted suicides were recorded in the database of the Instituto Nacional de Salud [National Health Institute] Sistema de Vigilancia de Salud Pública (SIVIGILA) [Public Health Surveillance System] in Colombia. 140 cases were excluded due to lack of relevant information such as age, gender and number of suicide attempts. 18,763 cases were analysed, corresponding to 99.3% of the total reports.

The information was compiled in an Excel® database designed for the purpose and exported to the SPSS programme version 20. A descriptive analysis of the study variables was performed. The mean (95% confidence interval [95% CI]) was used for continuous variables. For qualitative variables, frequencies were reported and proportions were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Strength of association was calculated with the odds ratio (OR) with its 95% CI. For the multivariate analysis, factors that presented significance (p≤0.05) and/or which were already identified in the literature as possible predictors of attempted suicide were taken into account for the comparison of proportions. These factors were included in the logistic regression by the single-step entry method.

Ethical implicationsThis research was carried out following the ethical regulations in force in Colombia (Resolution 008430 of 1993) and in the world (Declaration of Helsinki, modified in Edinburgh, 2000). Informed consent was not required. It was considered low risk in that the main concern was to maintain the confidentiality of the participants’ personal data. To guarantee confidentiality, the database was delivered to the authors encrypted with a password and with no data pertaining to the name and/or identification of the patients. The authors also signed a letter undertaking to guarantee information confidentiality and anonymity.

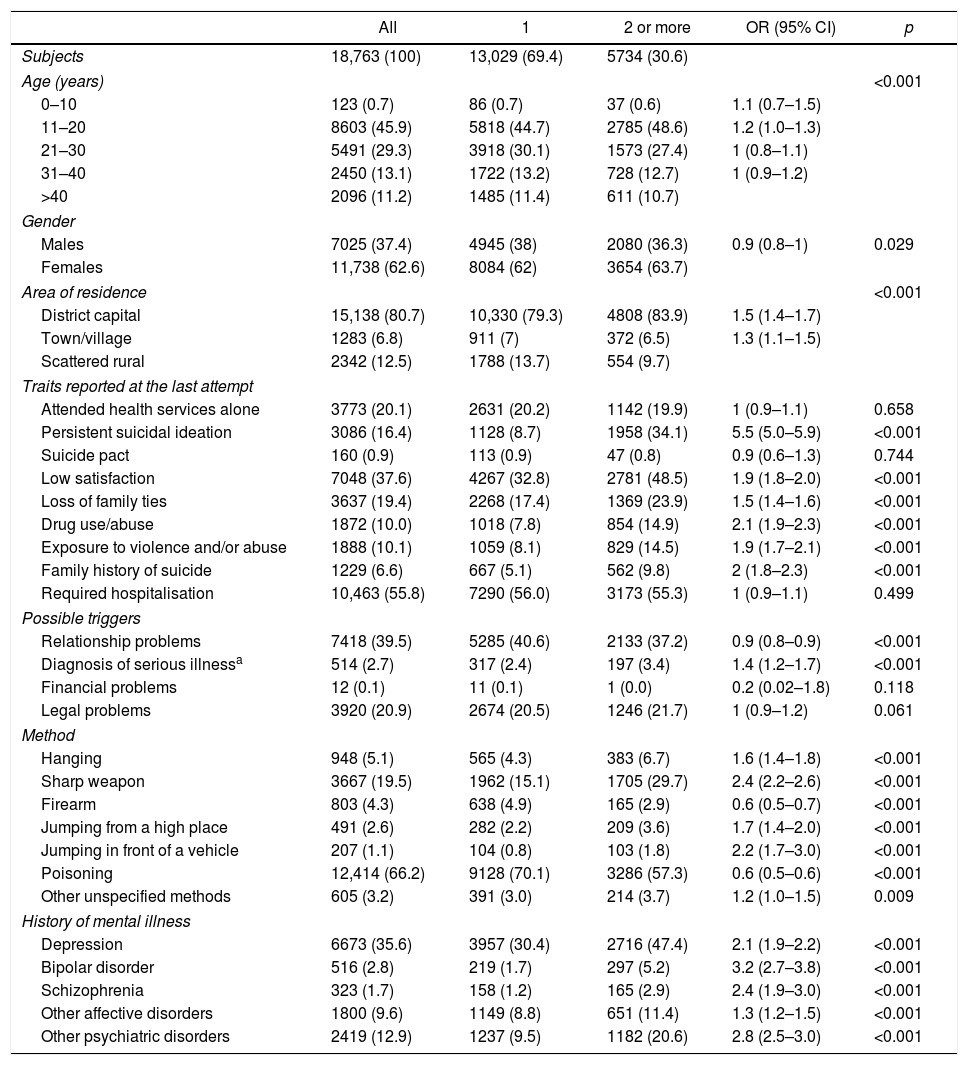

Results18,763 reports of attempted suicide reported to SIVIGILA in 2016 were analysed. In 11,738 (62.6%) cases the person was female. Mean age was 25.0 (95% CI, 24.9–25.2), with 46% aged 10–20, and 75% of all cases were aged 30 or under. The characteristics of the population grouped according to the number of suicide attempts are summarised in Table 1.

Characteristics of the people in Colombia who attempted suicide in 2016, classified by number of attempts.

| All | 1 | 2 or more | OR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects | 18,763 (100) | 13,029 (69.4) | 5734 (30.6) | ||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | ||||

| 0–10 | 123 (0.7) | 86 (0.7) | 37 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.7–1.5) | |

| 11–20 | 8603 (45.9) | 5818 (44.7) | 2785 (48.6) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | |

| 21–30 | 5491 (29.3) | 3918 (30.1) | 1573 (27.4) | 1 (0.8–1.1) | |

| 31–40 | 2450 (13.1) | 1722 (13.2) | 728 (12.7) | 1 (0.9–1.2) | |

| >40 | 2096 (11.2) | 1485 (11.4) | 611 (10.7) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Males | 7025 (37.4) | 4945 (38) | 2080 (36.3) | 0.9 (0.8–1) | 0.029 |

| Females | 11,738 (62.6) | 8084 (62) | 3654 (63.7) | ||

| Area of residence | <0.001 | ||||

| District capital | 15,138 (80.7) | 10,330 (79.3) | 4808 (83.9) | 1.5 (1.4–1.7) | |

| Town/village | 1283 (6.8) | 911 (7) | 372 (6.5) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | |

| Scattered rural | 2342 (12.5) | 1788 (13.7) | 554 (9.7) | ||

| Traits reported at the last attempt | |||||

| Attended health services alone | 3773 (20.1) | 2631 (20.2) | 1142 (19.9) | 1 (0.9–1.1) | 0.658 |

| Persistent suicidal ideation | 3086 (16.4) | 1128 (8.7) | 1958 (34.1) | 5.5 (5.0–5.9) | <0.001 |

| Suicide pact | 160 (0.9) | 113 (0.9) | 47 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.744 |

| Low satisfaction | 7048 (37.6) | 4267 (32.8) | 2781 (48.5) | 1.9 (1.8–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Loss of family ties | 3637 (19.4) | 2268 (17.4) | 1369 (23.9) | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | <0.001 |

| Drug use/abuse | 1872 (10.0) | 1018 (7.8) | 854 (14.9) | 2.1 (1.9–2.3) | <0.001 |

| Exposure to violence and/or abuse | 1888 (10.1) | 1059 (8.1) | 829 (14.5) | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) | <0.001 |

| Family history of suicide | 1229 (6.6) | 667 (5.1) | 562 (9.8) | 2 (1.8–2.3) | <0.001 |

| Required hospitalisation | 10,463 (55.8) | 7290 (56.0) | 3173 (55.3) | 1 (0.9–1.1) | 0.499 |

| Possible triggers | |||||

| Relationship problems | 7418 (39.5) | 5285 (40.6) | 2133 (37.2) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | <0.001 |

| Diagnosis of serious illnessa | 514 (2.7) | 317 (2.4) | 197 (3.4) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | <0.001 |

| Financial problems | 12 (0.1) | 11 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.02–1.8) | 0.118 |

| Legal problems | 3920 (20.9) | 2674 (20.5) | 1246 (21.7) | 1 (0.9–1.2) | 0.061 |

| Method | |||||

| Hanging | 948 (5.1) | 565 (4.3) | 383 (6.7) | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | <0.001 |

| Sharp weapon | 3667 (19.5) | 1962 (15.1) | 1705 (29.7) | 2.4 (2.2–2.6) | <0.001 |

| Firearm | 803 (4.3) | 638 (4.9) | 165 (2.9) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | <0.001 |

| Jumping from a high place | 491 (2.6) | 282 (2.2) | 209 (3.6) | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Jumping in front of a vehicle | 207 (1.1) | 104 (0.8) | 103 (1.8) | 2.2 (1.7–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Poisoning | 12,414 (66.2) | 9128 (70.1) | 3286 (57.3) | 0.6 (0.5–0.6) | <0.001 |

| Other unspecified methods | 605 (3.2) | 391 (3.0) | 214 (3.7) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 0.009 |

| History of mental illness | |||||

| Depression | 6673 (35.6) | 3957 (30.4) | 2716 (47.4) | 2.1 (1.9–2.2) | <0.001 |

| Bipolar disorder | 516 (2.8) | 219 (1.7) | 297 (5.2) | 3.2 (2.7–3.8) | <0.001 |

| Schizophrenia | 323 (1.7) | 158 (1.2) | 165 (2.9) | 2.4 (1.9–3.0) | <0.001 |

| Other affective disorders | 1800 (9.6) | 1149 (8.8) | 651 (11.4) | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | <0.001 |

| Other psychiatric disorders | 2419 (12.9) | 1237 (9.5) | 1182 (20.6) | 2.8 (2.5–3.0) | <0.001 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: crude odds ratio.

More than one suicide attempt was reported by 5734 participants (30.6%). Sociodemographic characteristics such as age group and gender presented no significant association with more than one suicide attempt, although there was a significant association with residing in the district capital or a town or village. The prevalence of persistent suicidal ideation was 16.4% and it was associated with more than one suicide attempt (OR=5.5; 95% CI, 5.0–5.9). Variables such as attending the health service alone, suicide pact, the need for hospitalisation and financial and legal problems were distributed similarly across both groups. Among the possible triggers, only the prior diagnosis of serious illness presented an association in the univariate analysis. With regard to the method used, a sharp weapon, hanging and jumping from a high building or into the path of a moving vehicle were associated with more than one suicide attempt, while firearms and self-poisoning were more associated with the first suicide attempt and were found to be protective factors against two or more suicide attempts (Table 1).

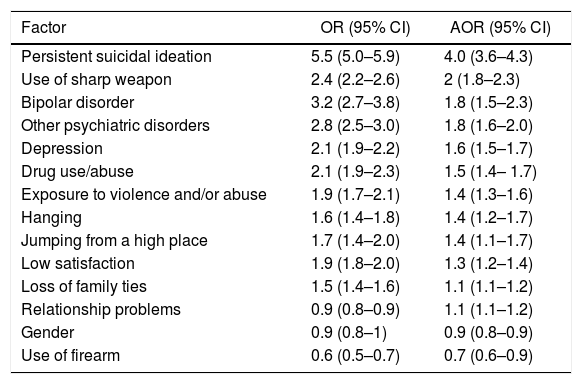

A history of mental illness was reported by 48.5% of the study population (9093) and was associated with more than one suicide attempt (OR=2.3; 95% CI, 2.1–2.4). The prevalence of depression and bipolar disorder were 35.6% and 2.8%, respectively, both of them independently associated with more than one suicide attempt. Following adjustment by logistic regression, the factor most associated with more than one suicide attempt was persistent suicidal ideation (OR=5.5; [95% CI, 5.0–5.9] and adjusted OR [AOR]=4.0 [95% CI, 3.6–4.3]), although other factors also presented an association (Table 2).

Factors associated with 2 or more suicide attempts in the Colombian population in 2016.

| Factor | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent suicidal ideation | 5.5 (5.0–5.9) | 4.0 (3.6–4.3) |

| Use of sharp weapon | 2.4 (2.2–2.6) | 2 (1.8–2.3) |

| Bipolar disorder | 3.2 (2.7–3.8) | 1.8 (1.5–2.3) |

| Other psychiatric disorders | 2.8 (2.5–3.0) | 1.8 (1.6–2.0) |

| Depression | 2.1 (1.9–2.2) | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) |

| Drug use/abuse | 2.1 (1.9–2.3) | 1.5 (1.4– 1.7) |

| Exposure to violence and/or abuse | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) |

| Hanging | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) |

| Jumping from a high place | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) |

| Low satisfaction | 1.9 (1.8–2.0) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) |

| Loss of family ties | 1.5 (1.4–1.6) | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) |

| Relationship problems | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) |

| Gender | 0.9 (0.8–1) | 0.9 (0.8–0.9) |

| Use of firearm | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: crude odds ratio; AOR: adjusted odds ratio.

Variables introduced to construct the model: persistent suicidal ideation, sharp weapon, bipolar disorder, depression, other psychiatric disorders (other than bipolar disorder, depression and schizophrenia), age, gender, area of residence, low personal satisfaction, loss of family ties, use and/or abuse of drugs, exposure to violence and/or abuse, history of suicide in the family, relationship problems, diagnosis of serious illness, hanging, firearm, jumping off a high place, intoxication and schizophrenia. Source: SIVIGILA (Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia en Salud Pública [National Public Health Surveillance System], Instituto Nacional de Salud [National Health Institute], Colombia, 2016.

Our results show that over 30% of people who attempted suicide in Colombia in 2016 had already done so, which does not differ greatly from the figure reported in the attempted suicide surveillance protocol (40%).7 The factor most associated with two or more suicide attempts was persistent suicidal ideation, which increased the likelihood of more than one suicide attempt four-fold in the Colombian population in 2016. However, this could be related to the fact that our study only included people who had already made at least one suicide attempt and had already overcome the instinctive fear of death which prevents many people from actually progressing to the suicide attempt, as described by Joiner's theory; they acquired the ability to commit suicide and that ability can increase with each attempt.3 Thus, as long as suicidal ideation persists, there is a greater likelihood of the person making another suicide attempt. This association had never been studied in the Colombian population. There are studies on risk factors for both suicidal ideation and suicide attempt, but the relationship between them had not been studied, as both are strong predictors of death by suicide.8,9

The prevalence of a history of mental illness was also high in this study, close to 50%; depression accounted for 35% of cases and was also more likely to be associated with two or more suicide attempts. This association had been described previously and had been explained, although not entirely, by the presence of hopelessness, anhedonia, high emotional reactivity and impulsiveness. The assumption was that each one of these characteristics can increase psychological distress to an unbearable extent and lead a person to suicide; particularly impulsiveness, which has been hypothesised as an important factor in the progression from planned to attempted suicide.6,10 Another earlier study conducted in Colombia also demonstrated an association between mental disorders and attempted suicide, without distinguishing between one and more attempts.9

In one year, 18,763 cases of attempted suicide were reported in Colombia. This number is large, considering that it was the first year that suicide attempts were monitored in Colombia as an event of public health interest. However, compared to the WHO figures, which infer that for every death by suicide there are 20 attempts, the notifications do not correspond to the magnitude of the event.

The mean age of 25 and the predominance of females among the participants are similar to other studies carried out in the Colombian population.8 It is striking that age did not present a significant association with more than one suicide attempt, when it has historically been associated with suicide and attempted suicide.3,6 However, perhaps these studies did not distinguish between one and two or more suicide attempts, or other types of studies are required to assess these variables better.

Among the possible triggers of attempted suicide, a prior diagnosis of serious illness presented an association; others, such as relationship problems, use or abuse of psychoactive substances and loss of family ties, were not associated, although they had previously been associated when no distinction was made between one or more attempts.8

In line with previous reports in the literature about Colombia,8,9,11 in most cases the method used for the attempted suicide was self-poisoning, followed by a sharp weapon. However, the use of a sharp weapon, hanging and jumping off a high structure or in front of a moving vehicle was also associated with two or more suicide attempts, which had not previously been described in the Colombian population.

The main limitation of our study is the secondary source of information (attempted suicide reports). It is important to note that while SIVIGILA is becoming increasingly more efficient, and the number of reports of events of public health interest is increasing, a great deal of work remains to be done to improve the reporting culture, particularly the quality of reports made by the different health institutions, as some are incomplete. It should also be borne in mind that only cases of attempted suicide dealt with by a health service are reported; cases in which no medical care was required for the suicide attempt are not recorded or reported, meaning that there will be a certain degree of under-reporting.

The main contribution of this work is to alert the scientific community to the need to identify factors associated with two or more attempts, such as persistent suicidal ideation and a history of mental illness (bipolar disorder and depression) in patients coming to the health service after attempted a suicide. The early detection of people with factors associated with more than one episode of attempted suicide, which makes them vulnerable to further attempts or to a consummated suicide, would help us design individual treatment and rehabilitation plans aimed at preventing suicide attempts.

ConclusionsPatients with persistent suicidal ideation were four times more likely to make two or more suicide attempts; those who used a sharp weapon as a method to attempt suicide and those with a history of bipolar disorder and depression were also more likely to make more than one attempt.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

To the Instituto Nacional de Salud for providing the data on attempted suicide reports for 2016 and to the territorial organisations for their diligent case reporting work.

Please cite this article as: Aparicio Castillo Y, Blandón Rodríguez AM, Chaves Torres NM. Alta prevalencia de dos o más intentos de suicidio asociados con ideación suicida y enfermedad mental en Colombia en 2016. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2020;49:95–100.