Bipolar disorder (BD) is reported to be the mental disorder with the highest rate of comorbidity with substance use disorders (SUD). More than half of patients with BD have been found to have disorders associated with alcohol use.

MethodsA secondary analysis was performed in a population sample of Colombian adults. The aim was to identify bipolar-alcohol comorbidity and factors related to the use of alcohol in people with BD. The diagnosis of BD among participants was made with the “Composite International Diagnostic Interview” (CIDI-CAPI) and the pattern of alcohol consumption in the last year was evaluated with the AUDIT C screening tool.

ResultsIt was found that all patients with BD had some type of problematic alcohol consumption pattern. Women with BD were at greater risk of having a dependence-type pattern, using nicotine and marijuana and, among those living in urban areas, had higher rates of suicidal ideation, although that risk was lower if they were in a stable relationship.

DiscussionSome of the related factors we identified are new with respect to previous publications and others have already been described in similar studies.

ConclusionsGiven the importance of such factors in the management of this population and their prognosis, these findings highlight the need to determine consumption patterns of alcohol and other substances in patients with BD.

El trastorno afectivo bipolar (TAB) es el trastorno mental reportada con mayor comorbilidad con el trastorno de abuso de sustancias (TAUS). Específicamente se han encontrado trastornos asociados con el consumo de alcohol (TACDA) en más de la mitad de los pacientes con TAB.

Material y métodosSe realizó un análisis secundario en una muestra poblacional de adultos en Colombia, con el objetivo de identificar la presencia de comorbilidad y los factores relacionados con el uso de alcohol en personas con TAB. El diagnóstico de TAB de los participantes se realizó a través del Entrevista Diagnóstica Internacional Compuesta (CIDI-CAPI) y el patrón de consumo de alcohol en el último año se determinó con la escala AUDIT C.

ResultadosSe encontró que todos los pacientes con diagnóstico de TAB tenían algún patrón desadaptativo de consumo de alcohol. Entre las mujeres con TAB de esta muestra, se encontró un mayor riesgo de consumo de tipo dependencia, también mayor riesgo de consumo de nicotina y marihuana; entre quienes viven en centros urbanos, una mayor frecuencia de ideas suicidas y entre aquellos en una relación de pareja estable, menos riesgo.

DiscusiónSe identificaron factores asociados novedosos respecto a publicaciones previas y otros ya descritos en estudios similares.

ConclusionesEstos hallazgos indican la necesidad de evaluar, en el abordaje de los pacientes con TAB, el tipo de consumo de alcohol y otras sustancias, dada su relevancia en el manejo y el pronóstico de esta población.

Alcohol addiction is a chronic condition that causes social, personal, work, financial and health deterioration in general in consumers.1 In Latin America, alcohol-related disorders have been reported as the eighth cause of disability-adjusted life years, and it is the leading cause of years lived with disability for men.2 There are multiple reports on the comorbidity of substance-use disorders (SUDs) and bipolar disorder (BD).3,4 This comorbidity has been related to worse prognosis, lower adherence to pharmacological treatments, lower response to treatment with lithium carbonate,5 greater number of episodes, more prolonged episodes,6 higher frequency of episodes with mixed symptoms,5,7 increased impulsiveness and suicide rates8,9 and lower functional recovery even during remission from consumption.10 As a result of all of the above, patients with this comorbidity make greater use of health services.11,12 Among the SUDs are alcohol use disorders (AUDs). These can be found in more than half of patients with BD,13 with a similar impact on development, severity and prognosis.

Several explanatory hypotheses have been suggested for the relationship between bipolar disorders and alcohol consumption. One of these is that patients are seeking to change their moods through the consumption of alcohol, which has been called "self-medication hypothesis".14 Interventions aimed at this population should take into account individual reasons and mood stabilisation should be prioritised. It is important to explore by risk factors associated with alcohol consumption in patients with BD and to detect alcohol use patterns, in order to address and treat this condition simultaneously.15

In Colombia and Latin America, there are few data on this comorbidity, as well as factors which promote or avoid the co-existence of these disorders. There are reports of greater frequency in men and a greater link to BD type I.16 This study is seeking to establish the frequency of the comorbidity and the factors related to the use of alcohol in individuals with BD in a population sample of adults in Colombia.

MethodsA secondary analysis of the Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental (National Mental Health Survey) in Colombia was carried out in 2015 (ENSM 2015). This study was carried out in a non-institutionalised civil population and had a total population sample of 15,351 people, 10,870 of whom were over the age of 18. It was based on an observational, descriptive cross-sectional study, from a probability sample. A secondary analysis was carried out and the population with the diagnosis of BD in the ENSM 2015 (n=131) was taken as the sample and categorised into BD I (n=110) and BD II and not classified (n=21); the alcohol use pattern in the past year was also assessed in these individuals, measured by the AUDIT-C, which is a scale used to identify maladaptive patterns of alcohol use and is interpreted in accordance with the responses into "no problem", "at-risk drinker" and "possible addiction". The scores which are considered positive of maladaptive alcohol use in women have a 73 % sensitivity and a 91 % specificity, and, in men, an 86 % sensitivity and an 89 % specificity.29

The data from the ENSM 2015 was obtained by means of surveys carried out by trained individuals, and the diagnosis of BD was carried out with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI-CAPI). The Ministry of Health supplied the ENSM 2015 database, along with the dictionaries of variables. All respondents were anonymised.

The instruments used in the ENSM are described in the "Methods" section of the document.17 The validity of the AUDIT-C test has been validated in Spanish, in several clinical and population samples, with reports of sensitivity for problematic consumption above 0.90 and specificity in values >0.80.18

Statistical analysisThe variables of interest were extracted and defined and subsequently a sub-database was created to compare each one of the variables with the categories of BD. The program Stata version 13.0 was used for the analysis. Measures of frequency, central tendency and dispersion were used for the univariate analysis in accordance with the classification and distribution. The distributions of characteristics of interest between those who had a risk consumption and a possible addiction according to the AUDIT-C questionnaire were then compared using the χ2 and Fisher’s exact statistical tests, as appropriate. The strength of association (odds ratio [OR]) with its 95 % confidence interval [95 % CI] between the dependent variables and the independent variables was determined, generating contingency tables of the possible explanatory variables, with two cut-off points according to the scale used to evaluate alcohol consumption (at-risk drinker and possible addiction). Stepwise logistic regression was then carried out, with a threshold of p=0.2. The statistically significant variables were selected which were included in the final model and exposure of interest in terms of interaction was evaluated.

Ethical considerationsThis study adheres to national regulations which regulate clinical research in Colombia according to resolutions 8430, of 1993 and resolution 2378 of 2008, and to international agreements on ethical research involving human subjects (Declaration of Helsinki). This is a descriptive study carried out on historical records where no intervention was carried out; therefore, the results of this research did not modify any diagnostic behaviour or follow-up or treatment and did not have any prognostic value for participants. For these reasons, it is considered a risk-free study. The Ministry of Health, in order to ensure the confidentiality and privacy of participants, granted a database of the ENSM 2015 without the identification of participants; in addition, no individual outside the investigation had access to the study data. In any case, the study was subjected to evaluation, and the ethics committee of the Clínica Valle de Lili endorsed it.

ResultsFrom the total sample of the ENSM 2015, 1.2 % (n=131) had a diagnosis of BD, 83.9 % (n=110) in the category BD I and 16.0 % (n=21) in the category BD II and not classified. The mean age of the respondents with BD I was 36.62±14.87 years and in the category BD II and not classified 35.5±17.27 years. No statistically significant differences were found between these.

None of the respondents with a diagnosis of BD had an AUDIT-C which complied with the category "no problem"; 64.9 % of the respondents with BD had a positive AUDIT-C for possible addiction and 35.1 % for risky consumption.

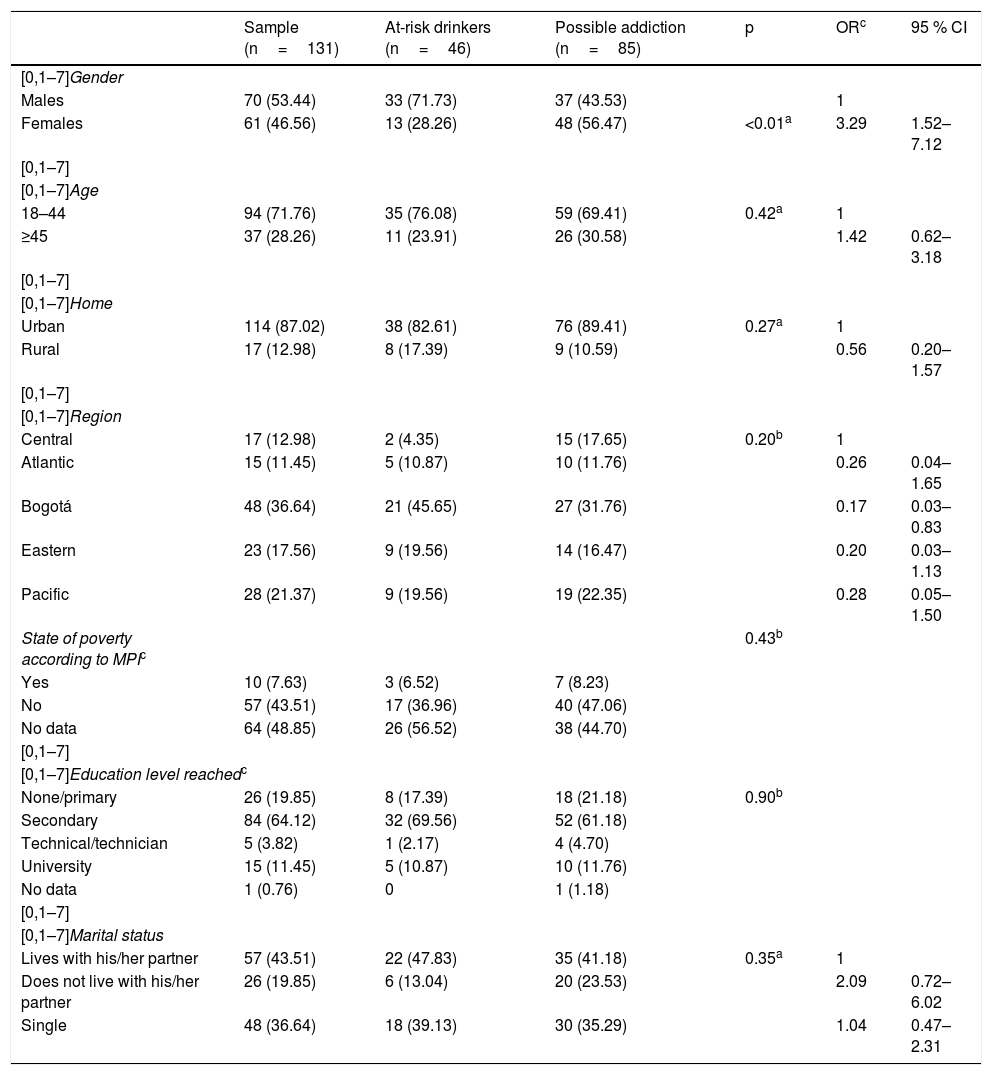

Of the ENSM 2015 respondents with a diagnosis of BD, 46.6 % were women. The average age of men with BD surveyed was 35.87±16.08 years, and that of women was 37.11±14.25 years. No statistically significant differences were found; 87 % lived in urban homes, 36.64 % were in the city of Bogotá, 7.63 % were in a situation of poverty according to the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), 19.8 % did not have an education or had completed primary education, 64.1 % had completed secondary education; 43.5 % lived with their partner (married or cohabiting) and 49.62 % were working at the time of responding to the survey. Table 1 describes the socio-demographic variables of the sample.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the population with BD in the ENSM 2015.

| Sample (n=131) | At-risk drinkers (n=46) | Possible addiction (n=85) | p | ORc | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–7]Gender | ||||||

| Males | 70 (53.44) | 33 (71.73) | 37 (43.53) | 1 | ||

| Females | 61 (46.56) | 13 (28.26) | 48 (56.47) | <0.01a | 3.29 | 1.52–7.12 |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Age | ||||||

| 18–44 | 94 (71.76) | 35 (76.08) | 59 (69.41) | 0.42a | 1 | |

| ≥45 | 37 (28.26) | 11 (23.91) | 26 (30.58) | 1.42 | 0.62–3.18 | |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Home | ||||||

| Urban | 114 (87.02) | 38 (82.61) | 76 (89.41) | 0.27a | 1 | |

| Rural | 17 (12.98) | 8 (17.39) | 9 (10.59) | 0.56 | 0.20–1.57 | |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Region | ||||||

| Central | 17 (12.98) | 2 (4.35) | 15 (17.65) | 0.20b | 1 | |

| Atlantic | 15 (11.45) | 5 (10.87) | 10 (11.76) | 0.26 | 0.04–1.65 | |

| Bogotá | 48 (36.64) | 21 (45.65) | 27 (31.76) | 0.17 | 0.03–0.83 | |

| Eastern | 23 (17.56) | 9 (19.56) | 14 (16.47) | 0.20 | 0.03–1.13 | |

| Pacific | 28 (21.37) | 9 (19.56) | 19 (22.35) | 0.28 | 0.05–1.50 | |

| State of poverty according to MPIc | 0.43b | |||||

| Yes | 10 (7.63) | 3 (6.52) | 7 (8.23) | |||

| No | 57 (43.51) | 17 (36.96) | 40 (47.06) | |||

| No data | 64 (48.85) | 26 (56.52) | 38 (44.70) | |||

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Education level reachedc | ||||||

| None/primary | 26 (19.85) | 8 (17.39) | 18 (21.18) | 0.90b | ||

| Secondary | 84 (64.12) | 32 (69.56) | 52 (61.18) | |||

| Technical/technician | 5 (3.82) | 1 (2.17) | 4 (4.70) | |||

| University | 15 (11.45) | 5 (10.87) | 10 (11.76) | |||

| No data | 1 (0.76) | 0 | 1 (1.18) | |||

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Marital status | ||||||

| Lives with his/her partner | 57 (43.51) | 22 (47.83) | 35 (41.18) | 0.35a | 1 | |

| Does not live with his/her partner | 26 (19.85) | 6 (13.04) | 20 (23.53) | 2.09 | 0.72–6.02 | |

| Single | 48 (36.64) | 18 (39.13) | 30 (35.29) | 1.04 | 0.47–2.31 | |

95 % CI: 95 % confidence interval; OR: crude odds ratio.

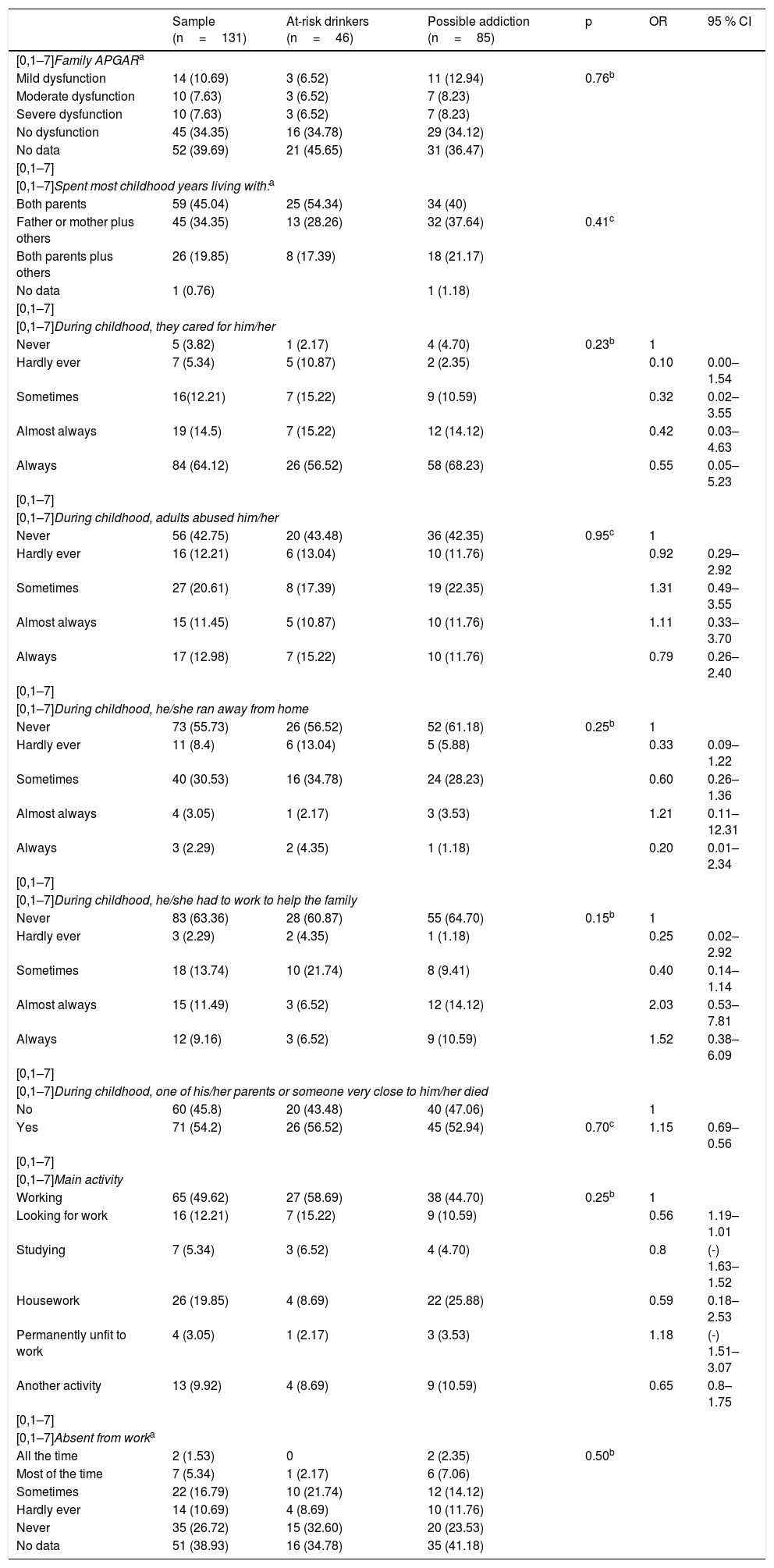

A total of 25.9 % of the population declared some degree of family dysfunction and 45 % lived their childhood years (up to the age of 12) with both parents; 24.3 % reported that they were always or almost always abused in their childhood, and 54.2 % experienced the death of one of their parents or a person close to them during childhood. Table 2 summarises the social characteristics of the population with BD.

Social characteristics of the sample.

| Sample (n=131) | At-risk drinkers (n=46) | Possible addiction (n=85) | p | OR | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–7]Family APGARa | ||||||

| Mild dysfunction | 14 (10.69) | 3 (6.52) | 11 (12.94) | 0.76b | ||

| Moderate dysfunction | 10 (7.63) | 3 (6.52) | 7 (8.23) | |||

| Severe dysfunction | 10 (7.63) | 3 (6.52) | 7 (8.23) | |||

| No dysfunction | 45 (34.35) | 16 (34.78) | 29 (34.12) | |||

| No data | 52 (39.69) | 21 (45.65) | 31 (36.47) | |||

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Spent most childhood years living with:a | ||||||

| Both parents | 59 (45.04) | 25 (54.34) | 34 (40) | |||

| Father or mother plus others | 45 (34.35) | 13 (28.26) | 32 (37.64) | 0.41c | ||

| Both parents plus others | 26 (19.85) | 8 (17.39) | 18 (21.17) | |||

| No data | 1 (0.76) | 1 (1.18) | ||||

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]During childhood, they cared for him/her | ||||||

| Never | 5 (3.82) | 1 (2.17) | 4 (4.70) | 0.23b | 1 | |

| Hardly ever | 7 (5.34) | 5 (10.87) | 2 (2.35) | 0.10 | 0.00–1.54 | |

| Sometimes | 16(12.21) | 7 (15.22) | 9 (10.59) | 0.32 | 0.02–3.55 | |

| Almost always | 19 (14.5) | 7 (15.22) | 12 (14.12) | 0.42 | 0.03–4.63 | |

| Always | 84 (64.12) | 26 (56.52) | 58 (68.23) | 0.55 | 0.05–5.23 | |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]During childhood, adults abused him/her | ||||||

| Never | 56 (42.75) | 20 (43.48) | 36 (42.35) | 0.95c | 1 | |

| Hardly ever | 16 (12.21) | 6 (13.04) | 10 (11.76) | 0.92 | 0.29–2.92 | |

| Sometimes | 27 (20.61) | 8 (17.39) | 19 (22.35) | 1.31 | 0.49–3.55 | |

| Almost always | 15 (11.45) | 5 (10.87) | 10 (11.76) | 1.11 | 0.33–3.70 | |

| Always | 17 (12.98) | 7 (15.22) | 10 (11.76) | 0.79 | 0.26–2.40 | |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]During childhood, he/she ran away from home | ||||||

| Never | 73 (55.73) | 26 (56.52) | 52 (61.18) | 0.25b | 1 | |

| Hardly ever | 11 (8.4) | 6 (13.04) | 5 (5.88) | 0.33 | 0.09–1.22 | |

| Sometimes | 40 (30.53) | 16 (34.78) | 24 (28.23) | 0.60 | 0.26–1.36 | |

| Almost always | 4 (3.05) | 1 (2.17) | 3 (3.53) | 1.21 | 0.11–12.31 | |

| Always | 3 (2.29) | 2 (4.35) | 1 (1.18) | 0.20 | 0.01–2.34 | |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]During childhood, he/she had to work to help the family | ||||||

| Never | 83 (63.36) | 28 (60.87) | 55 (64.70) | 0.15b | 1 | |

| Hardly ever | 3 (2.29) | 2 (4.35) | 1 (1.18) | 0.25 | 0.02–2.92 | |

| Sometimes | 18 (13.74) | 10 (21.74) | 8 (9.41) | 0.40 | 0.14–1.14 | |

| Almost always | 15 (11.49) | 3 (6.52) | 12 (14.12) | 2.03 | 0.53–7.81 | |

| Always | 12 (9.16) | 3 (6.52) | 9 (10.59) | 1.52 | 0.38–6.09 | |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]During childhood, one of his/her parents or someone very close to him/her died | ||||||

| No | 60 (45.8) | 20 (43.48) | 40 (47.06) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 71 (54.2) | 26 (56.52) | 45 (52.94) | 0.70c | 1.15 | 0.69–0.56 |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Main activity | ||||||

| Working | 65 (49.62) | 27 (58.69) | 38 (44.70) | 0.25b | 1 | |

| Looking for work | 16 (12.21) | 7 (15.22) | 9 (10.59) | 0.56 | 1.19–1.01 | |

| Studying | 7 (5.34) | 3 (6.52) | 4 (4.70) | 0.8 | (-) 1.63–1.52 | |

| Housework | 26 (19.85) | 4 (8.69) | 22 (25.88) | 0.59 | 0.18–2.53 | |

| Permanently unfit to work | 4 (3.05) | 1 (2.17) | 3 (3.53) | 1.18 | (-) 1.51–3.07 | |

| Another activity | 13 (9.92) | 4 (8.69) | 9 (10.59) | 0.65 | 0.8–1.75 | |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Absent from worka | ||||||

| All the time | 2 (1.53) | 0 | 2 (2.35) | 0.50b | ||

| Most of the time | 7 (5.34) | 1 (2.17) | 6 (7.06) | |||

| Sometimes | 22 (16.79) | 10 (21.74) | 12 (14.12) | |||

| Hardly ever | 14 (10.69) | 4 (8.69) | 10 (11.76) | |||

| Never | 35 (26.72) | 15 (32.60) | 20 (23.53) | |||

| No data | 51 (38.93) | 16 (34.78) | 35 (41.18) | |||

95 % CI: 95 % confidence interval; OR: crude odds ratio.

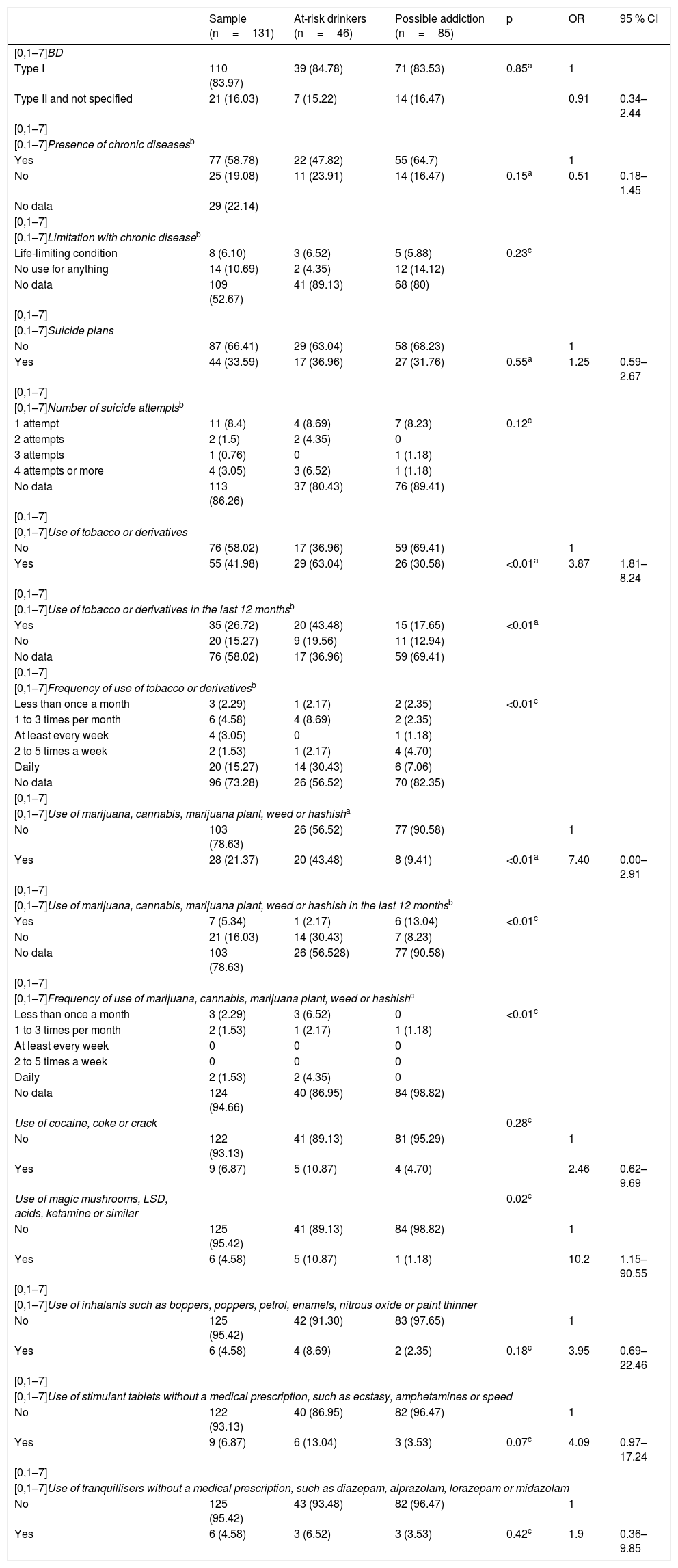

A total of 58.78 % of respondents reported chronic diseases; 33.58 % indicated having had suicide plans and 12.7 % having made one or more suicide attempts.

Of the total sample, 41.98 % of the sample used tobacco and its derivatives; 21.37 % had used marijuana; 6.87 % had used cocaine at some point in their life, and use of opioids was not reported in the sample.

It was found that the risk of alcohol addiction in the women surveyed is greater than that of the men surveyed (OR=3.29; 95 % CI, 1.52–7.12; p<0.01). People with BD and alcohol use with a possible addiction have a higher risk of using tobacco or its derivatives than those who do not consume alcohol (OR=3.87; 95 % CI, 1.81–8.24; p<0.01) and a higher risk of using magic mushrooms, LSD or acids (OR=10.24; 95 % CI, 1.15–90.55; p=0.02). The clinical characteristics of the sample are mentioned in Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Sample (n=131) | At-risk drinkers (n=46) | Possible addiction (n=85) | p | OR | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–7]BD | ||||||

| Type I | 110 (83.97) | 39 (84.78) | 71 (83.53) | 0.85a | 1 | |

| Type II and not specified | 21 (16.03) | 7 (15.22) | 14 (16.47) | 0.91 | 0.34–2.44 | |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Presence of chronic diseasesb | ||||||

| Yes | 77 (58.78) | 22 (47.82) | 55 (64.7) | 1 | ||

| No | 25 (19.08) | 11 (23.91) | 14 (16.47) | 0.15a | 0.51 | 0.18–1.45 |

| No data | 29 (22.14) | |||||

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Limitation with chronic diseaseb | ||||||

| Life-limiting condition | 8 (6.10) | 3 (6.52) | 5 (5.88) | 0.23c | ||

| No use for anything | 14 (10.69) | 2 (4.35) | 12 (14.12) | |||

| No data | 109 (52.67) | 41 (89.13) | 68 (80) | |||

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Suicide plans | ||||||

| No | 87 (66.41) | 29 (63.04) | 58 (68.23) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 44 (33.59) | 17 (36.96) | 27 (31.76) | 0.55a | 1.25 | 0.59–2.67 |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Number of suicide attemptsb | ||||||

| 1 attempt | 11 (8.4) | 4 (8.69) | 7 (8.23) | 0.12c | ||

| 2 attempts | 2 (1.5) | 2 (4.35) | 0 | |||

| 3 attempts | 1 (0.76) | 0 | 1 (1.18) | |||

| 4 attempts or more | 4 (3.05) | 3 (6.52) | 1 (1.18) | |||

| No data | 113 (86.26) | 37 (80.43) | 76 (89.41) | |||

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Use of tobacco or derivatives | ||||||

| No | 76 (58.02) | 17 (36.96) | 59 (69.41) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 55 (41.98) | 29 (63.04) | 26 (30.58) | <0.01a | 3.87 | 1.81–8.24 |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Use of tobacco or derivatives in the last 12 monthsb | ||||||

| Yes | 35 (26.72) | 20 (43.48) | 15 (17.65) | <0.01a | ||

| No | 20 (15.27) | 9 (19.56) | 11 (12.94) | |||

| No data | 76 (58.02) | 17 (36.96) | 59 (69.41) | |||

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Frequency of use of tobacco or derivativesb | ||||||

| Less than once a month | 3 (2.29) | 1 (2.17) | 2 (2.35) | <0.01c | ||

| 1 to 3 times per month | 6 (4.58) | 4 (8.69) | 2 (2.35) | |||

| At least every week | 4 (3.05) | 0 | 1 (1.18) | |||

| 2 to 5 times a week | 2 (1.53) | 1 (2.17) | 4 (4.70) | |||

| Daily | 20 (15.27) | 14 (30.43) | 6 (7.06) | |||

| No data | 96 (73.28) | 26 (56.52) | 70 (82.35) | |||

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Use of marijuana, cannabis, marijuana plant, weed or hashisha | ||||||

| No | 103 (78.63) | 26 (56.52) | 77 (90.58) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 28 (21.37) | 20 (43.48) | 8 (9.41) | <0.01a | 7.40 | 0.00–2.91 |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Use of marijuana, cannabis, marijuana plant, weed or hashish in the last 12 monthsb | ||||||

| Yes | 7 (5.34) | 1 (2.17) | 6 (13.04) | <0.01c | ||

| No | 21 (16.03) | 14 (30.43) | 7 (8.23) | |||

| No data | 103 (78.63) | 26 (56.528) | 77 (90.58) | |||

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Frequency of use of marijuana, cannabis, marijuana plant, weed or hashishc | ||||||

| Less than once a month | 3 (2.29) | 3 (6.52) | 0 | <0.01c | ||

| 1 to 3 times per month | 2 (1.53) | 1 (2.17) | 1 (1.18) | |||

| At least every week | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 2 to 5 times a week | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Daily | 2 (1.53) | 2 (4.35) | 0 | |||

| No data | 124 (94.66) | 40 (86.95) | 84 (98.82) | |||

| Use of cocaine, coke or crack | 0.28c | |||||

| No | 122 (93.13) | 41 (89.13) | 81 (95.29) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 9 (6.87) | 5 (10.87) | 4 (4.70) | 2.46 | 0.62–9.69 | |

| Use of magic mushrooms, LSD, acids, ketamine or similar | 0.02c | |||||

| No | 125 (95.42) | 41 (89.13) | 84 (98.82) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 6 (4.58) | 5 (10.87) | 1 (1.18) | 10.2 | 1.15–90.55 | |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Use of inhalants such as boppers, poppers, petrol, enamels, nitrous oxide or paint thinner | ||||||

| No | 125 (95.42) | 42 (91.30) | 83 (97.65) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 6 (4.58) | 4 (8.69) | 2 (2.35) | 0.18c | 3.95 | 0.69–22.46 |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Use of stimulant tablets without a medical prescription, such as ecstasy, amphetamines or speed | ||||||

| No | 122 (93.13) | 40 (86.95) | 82 (96.47) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 9 (6.87) | 6 (13.04) | 3 (3.53) | 0.07c | 4.09 | 0.97–17.24 |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Use of tranquillisers without a medical prescription, such as diazepam, alprazolam, lorazepam or midazolam | ||||||

| No | 125 (95.42) | 43 (93.48) | 82 (96.47) | 1 | ||

| Yes | 6 (4.58) | 3 (6.52) | 3 (3.53) | 0.42c | 1.9 | 0.36–9.85 |

95 % CI: 95 % confidence interval; OR: crude odds ratio.

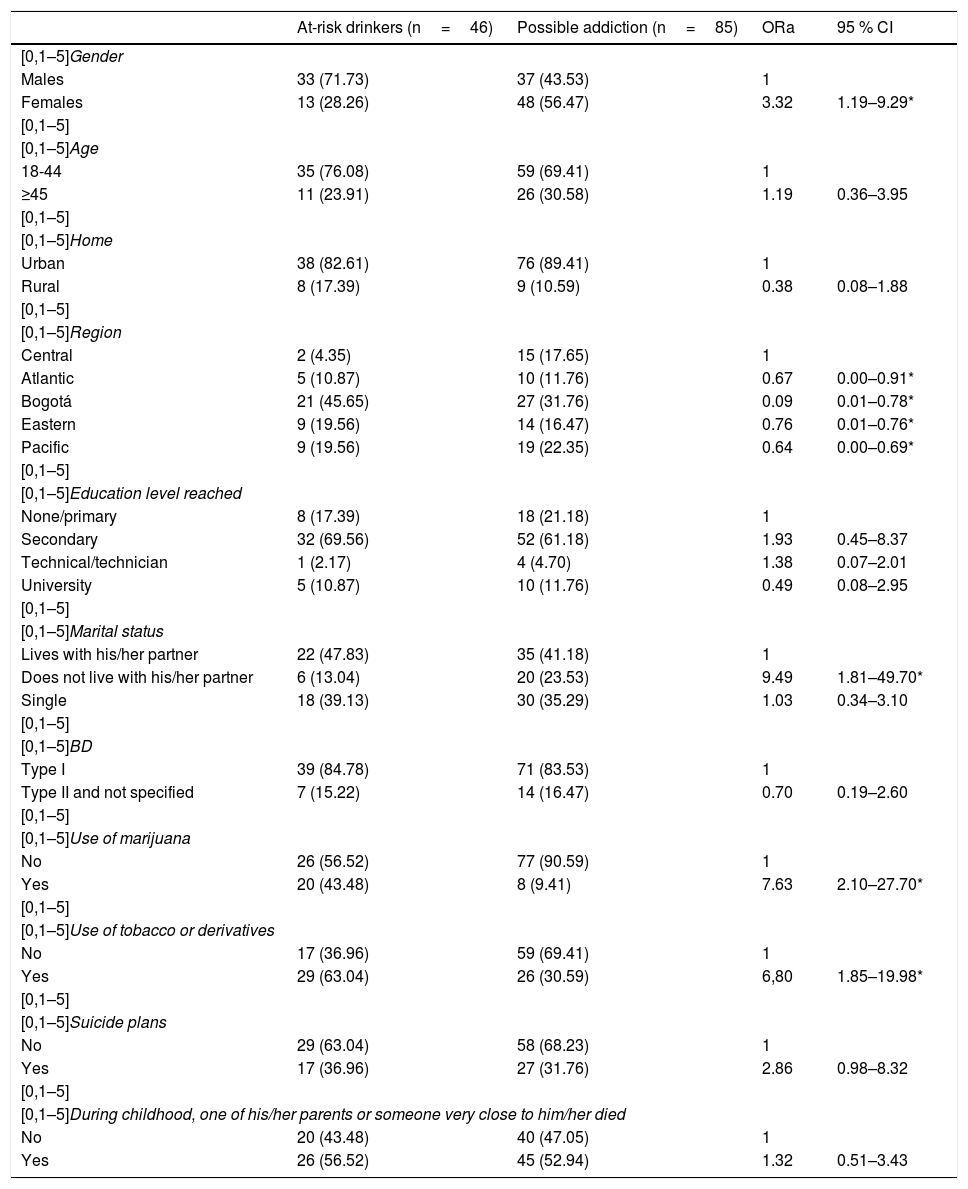

A multiple regression model was performed to obtain the adjusted OR for age, type of BD and place of residency. The result of this model was that the risk of women with BD remains higher than that of men (OR=3.32), as well as for people who do not live with their partners (OR=9.49), people older than 45 (OR=1.19) and those who experienced the death of a loved one in their childhood (OR=1.32).

People with this comorbidity have a 6.8 times higher risk of using tobacco than those who do not use it and also a seven times higher risk of using marijuana. This also occurs with the risk of having suicide plans (OR=2.86). Finally, those who have a university education (OR=0.49) or live in the city of Bogotá (OR=0.09) have less probability of suffering from the comorbidity. Table 4 summarises the multivariate analysis.

Multivariate analysis.

| At-risk drinkers (n=46) | Possible addiction (n=85) | ORa | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–5]Gender | ||||

| Males | 33 (71.73) | 37 (43.53) | 1 | |

| Females | 13 (28.26) | 48 (56.47) | 3.32 | 1.19–9.29* |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Age | ||||

| 18-44 | 35 (76.08) | 59 (69.41) | 1 | |

| ≥45 | 11 (23.91) | 26 (30.58) | 1.19 | 0.36–3.95 |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Home | ||||

| Urban | 38 (82.61) | 76 (89.41) | 1 | |

| Rural | 8 (17.39) | 9 (10.59) | 0.38 | 0.08–1.88 |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Region | ||||

| Central | 2 (4.35) | 15 (17.65) | 1 | |

| Atlantic | 5 (10.87) | 10 (11.76) | 0.67 | 0.00–0.91* |

| Bogotá | 21 (45.65) | 27 (31.76) | 0.09 | 0.01–0.78* |

| Eastern | 9 (19.56) | 14 (16.47) | 0.76 | 0.01–0.76* |

| Pacific | 9 (19.56) | 19 (22.35) | 0.64 | 0.00–0.69* |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Education level reached | ||||

| None/primary | 8 (17.39) | 18 (21.18) | 1 | |

| Secondary | 32 (69.56) | 52 (61.18) | 1.93 | 0.45–8.37 |

| Technical/technician | 1 (2.17) | 4 (4.70) | 1.38 | 0.07–2.01 |

| University | 5 (10.87) | 10 (11.76) | 0.49 | 0.08–2.95 |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Marital status | ||||

| Lives with his/her partner | 22 (47.83) | 35 (41.18) | 1 | |

| Does not live with his/her partner | 6 (13.04) | 20 (23.53) | 9.49 | 1.81–49.70* |

| Single | 18 (39.13) | 30 (35.29) | 1.03 | 0.34–3.10 |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]BD | ||||

| Type I | 39 (84.78) | 71 (83.53) | 1 | |

| Type II and not specified | 7 (15.22) | 14 (16.47) | 0.70 | 0.19–2.60 |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Use of marijuana | ||||

| No | 26 (56.52) | 77 (90.59) | 1 | |

| Yes | 20 (43.48) | 8 (9.41) | 7.63 | 2.10–27.70* |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Use of tobacco or derivatives | ||||

| No | 17 (36.96) | 59 (69.41) | 1 | |

| Yes | 29 (63.04) | 26 (30.59) | 6,80 | 1.85–19.98* |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]Suicide plans | ||||

| No | 29 (63.04) | 58 (68.23) | 1 | |

| Yes | 17 (36.96) | 27 (31.76) | 2.86 | 0.98–8.32 |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5]During childhood, one of his/her parents or someone very close to him/her died | ||||

| No | 20 (43.48) | 40 (47.05) | 1 | |

| Yes | 26 (56.52) | 45 (52.94) | 1.32 | 0.51–3.43 |

95 % CI: 95 % confidence interval; ORa: adjusted odds ratio.

All patients identified with a diagnosis of BD from this Colombian population sample had some maladaptive pattern of alcohol use, measured with AUDIT-C. In accordance with this finding, there are meta-analyses that report that people with alcohol use disorders have a 4.1 times greater risk of suffering from BD than those who do not have the comorbidity.19

In the ENSM 2015, it was estimated that the lifetime prevalence of BD I in adults of the Colombian population was significantly higher than that of BD II or not classified. A higher prevalence of AUDs in patients with BD I than with BD II was reported20; in our study, it was also found that respondents with BD I were at a higher risk of having an alcohol addiction drinking pattern, although this relationship was not statistically significant.21

It has been reported that men with BD have a two to three times total higher risk of AUD than women22; in Colombia, there are few data on this association, as well as factors which facilitate this comorbidity. However, it has been observed that it presents mostly in men and is greater in patients with BD I.16 In the ENSM 2015, it was found that approximately one tenth of the general population who participated in the survey had a problem with alcohol consumption, which was more common in men, and the highest consumption was found in men aged 18–24. These data are consistent, given that in the population with BD the highest consumption occurred in the young adult population; however, women with BD have a higher risk of dependency-type use, but in general terms the entire population with BD in this sample had some degree of harmful or dependency-type use, according to the instruments used.

With regard to the adult population over the age of 45, excess alcohol use in the population with BD was double that of the general population in this age group.23 Furthermore, it has been published that, despite the fact that men in the general population have a higher prevalence of problems related to alcohol use throughout life, women with BD are more vulnerable to suffering from alcoholism than men with BD.24

Despite the findings related to a history of abuse, adverse childhood experiences or experiencing grief in childhood of patients with BD, none of these variables was statistically significant in the multivariate analysis. This finding may be due to the size of the sub-sample of patients with BD found in this population sample and may be more common in clinical samples.

Individuals with BD associated with SUDs presented high rates of nicotine use,25 which is compatible with the results of this study, despite the fact that cigarette smoking does not predict a worsening of the course of BD, it is associated with an increase in the development of disorders related to alcohol and cannabis, in particular in adolescents with BD.26

It has been reported repeatedly that the population with this comorbidity has a greater risk of suicide attempts27; they also have a higher risk of comorbidity with disorders related to the use of other drugs,13 findings that are consistent with the results of this study, as a third of the population with BD had made a suicide plan and, of this third, more than half had an addiction pattern with other substances. The literature also reports that patients who are mentally ill and have an AUD have a greater risk of completing suicide.28,29

In up to 57 % of patients with alcohol use, it is associated with a dependency on marijuana and, in up to 73 %, with the use of cocaine and other stimulant drugs30,31; these findings are consistent with ours, as the individuals with BD and an alcohol addiction pattern used marijuana and cocaine more frequently than those who only had a risk use pattern; it is noteworthy that no respondent with BD used opioids.

The relationship between the comorbidities of patients with BD seems to occur partly due to a repeatable factor in the analyses of epidemiological samples, which is characterised by two validated dimensions and reported in the literature, the internalising dimension (comorbidity with unipolar depression and anxiety disorders) and the externalising dimension (comorbidity with substance use and impulsive behaviour or antisocial disorders). There is probably a third variable in this association which is still not clearly defined.32

Among the limitations of this study, the first is the size of the sample, which probably made it impossible to analyse variables such as adverse childhood experiences or family dysfunction. As with any type of secondary analysis, it is important to mention that this study was not designed to respond to the question that this study poses. Furthermore, it was not possible to evaluate the presence of other types of comorbidities with anxiety disorders. Nor was it possible to evaluate the probability of suffering from mixed symptoms and rapid cycles in comparison with patients with BD without alcohol-related disorders,14 the age of onset of the affective disorder,30 the cognitive effects, increased impulsiveness8,9 and the expenditure generated in the health services.11,12 It should be remembered that this is a secondary analysis of a database collected by third parties; the authors of this article did not participate in the selecting of the analysis variables or the way of doing it.

With regard to strengths, various can be described; this study is one of the first in Colombia16 in the general population which analyses the use of substances in people with a diagnosis of BD. The scales and interviews are validated and have been widely used in multiple studies in the clinical and general population. Furthermore, the sampling made it possible to extrapolate the results to regional and national levels in Colombia.

In conclusion, related factors which had already been previously reported in studies in other countries and regions were identified, such as the risk of using other psychoactive substances in patients with BD consuming alcohol and the higher risk of suicide thoughts and attempts; in addition, and in a striking way, a higher risk of alcohol addiction was found in this study in women with BD; this may be explained by unmeasured cultural or characterological reasons which should continue to be explored.

These findings indicate the need to re-evaluate the approach and treatment of patients with BD in relation to the comorbidity with SUDs.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank the Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection for the information necessary to carry out this study. We would also like to thank the Clinical Research Centre and Andrés Castro for their collaboration.

Please cite this article as: M. Castillo A, et al. Consumo de alcohol y diagnóstico de trastorno afectivo bipolar en población adulta colombiana. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:44–52.