Brachial plexus block as an anesthetic technique for upper limb surgery has some advantages over general anesthesia. The technique is widely used in our practice, with high effectiveness and adequate safety profile. However, the relationship between block failure and failure-determining factors has not been measured.

ObjectivesTo identify and quantify brachial plexus block failure-associated factors for upper limb surgery as an initial observation aimed at developing prevention-oriented risk profiles and strategies.

Materials and methodsAn analytical observational study was conducted by collecting data from electronic medical records of upper limb surgery using brachial plexus block from the San Ignacio University Hospital between 2011 and 2012. Block failures were identified using standardized clinical criteria, measuring potentially associated factors. Dichotomous comparisons were made and uni-and multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify potential statistically significant variables, based on failed cases and successful controls.

ResultsNone of the proposed factors was independently associated with failure of brachial plexus block. A qualitative description of failed cases presented confounding factors associated with local practices and the failure characteristics did not show a clinically plausible trend.

ConclusionsThere were no factors determined by patient, anesthetic procedure, surgical procedure and operator that could be independently associated with brachial plexus block failure. The suggestion is to fine-tune the definition of failures, not just in the research environment, but in the current clinical practice; to improve the anesthesia records to rise the numbers and the quality of data bases for a quantitative determination of the risk of peripheral regional anesthesia failure and design prevention strategies focused on risk groups.

El bloqueo de plexo braquial como técnica anestésica para cirugía de extremidad superior presenta ventajas sobre la anestesia general. Es ampliamente usada en nuestro medio con alta efectividad y adecuado perfil de seguridad. Sin embargo, no existe la cuantificación de las asociaciones entre fallo del bloqueo y factores determinantes del fallo.

ObjetivosIdentificar y cuantificar los factores asociados al fallo del bloqueo de plexo braquial como observación inicial para crear perfiles de riesgo y estrategias para prevenirlo.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un estudio observacional analítico, recolectando los datos de historias clínicas de bloqueos de plexo braquial para cirugía de miembro superior del Hospital Universitario San Ignacio de los años 2011-2012, identificando los bloqueos fallidos con criterios clínicos estandarizados, midiendo los factores potencialmente asociados a estos. Partiendo del grupo de fallos (casos) y grupo exitoso (controles) se establecieron comparaciones dicotómicas y análisis de regresión logística con análisis uni- y multivariado para identificar variables con significancia estadística.

ResultadosNinguno de los factores propuestos se asoció de forma independiente al fallo de bloqueo de plexo braquial. La descripción cualitativa de los casos fallidos presenta factores de confusión asociados a prácticas clínicas locales y ninguna tendencia clínicamente plausible en la característica de los fallos.

ConclusionesNingún factor determinado por el paciente, procedimiento anestésico, procedimiento quirúrgico, operador se asocia de forma independiente a fallo del bloqueo de plexo braquial. Se propone afinar la definición de fallo, no solo en el contexto investigativo, si no en la práctica clínica actual, mejorar los sistemas de registro en anestesia para ampliar en número y calidad las bases de datos que permitan aproximarse cuantitativamente al riesgo de fallo de anestesia regional periférica y plantear estrategias de prevención enfocadas en grupos de riesgo.

Regional anesthesia in the brachial plexus has several clinical applications and multiple advantages over general anesthesia in upper limb surgery, including better postoperative analgesia,1,2 lower opioid use,3–5 less postoperative nausea and vomiting6–8 and, consequently, decreased use of antiemetics, shorter time to ambulation and hospital discharge6,9,10 and shorter PACU stay.8–10 These advantages explain the growing interest and use by anesthesiologists around the world.

Ultrasonography applied to regional anesthesia has proven to lower the dose and volume of the local anesthetic agent required.11,12 In other words, there is a lower probability of systemic toxicity from local anesthetic agents, enables real time visualization of the needle with respect to the tissues identified, hence reducing the probability of both mechanical and systemic injury (puncture and vascular injection, pleural puncture, peripheral nerve injury, puncture and visceral injury, etc.),13,14 decreases the number of punctures and thus improves patient satisfaction and comfort,13 in addition to increasing the success rate for some approaches.12

Observational studies suggest patient and operator-dependent factors and the technique used may impact the success of the brachial plexus bocks. Patients with preoperative anxiety15 and elevated body mass index (BMI)5,16,17 present more frequent failures. Success may depend on the approach,18,19 the needle size in the transarterial technique,20 the guide,21,22 the peripheral nerve stimulation threshold, the volume and total dose of the local anesthetic12 and the number of injections administered.16,23,24 The operator's training and experience are crucial for the success or failure of the procedure.25

ObjectiveTo identify factors associated with brachial plexus block failure with supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary approach in surgery of the distal humerus, the elbow, the forearm, and hand at the HUSI between 2011 and 2012.

Materials and methodsPrevious approval by the Research and Institutional Ethics Committee of the San Ignacio University Hospital (HUSI) (record 2013-57), data of electronic medical records were collected and analyzed of all patients that underwent brachial plexus block using the approaches described for surgeries of the distal humerus, the elbow, the forearm, the hand at the HUSI between 2011 and 2012. This time period was chosen because it represents a stable practice of regional anesthesia based on the guidelines used (neurostimulation, ultrasound or dual) and operators (anesthesiologists with and without additional training in regional anesthesia) at the HUSI.

Interscalene blocks and pediatric (<14 years old) patient blocks were excluded because these are usually accompanied by general anesthesia prior to the surgical incision.

The definition of failed brachial plexus block is accepted when complying with anyone of the following: (1) Onset of general anesthesia (GA) after the surgical incision; (2) Use of opioid intravenous analgesics greater or equal to 100μg of fentanyl or its equivalent following the surgical incision; (3) Rescue peripheral nerve block (second block after completion of the initial block); or (4) Surgeon infiltration of local anesthetic agents into the surgical site.26 The use of intravenous sedatives or hypnotics was not included since these agents are usually administered during Monitored Anesthesia Care (MAC) and present variable pharmacodynamics responses among patients, hindering the determination of the cut points between GA and MAC. The four criteria comprising our definition of failures were chosen because they are routinely recorded in the electronic medical records at the HUSI and have been accepted in previous research papers.26

Additionally, the patient's demographic data were collected (gender, age, weight, height, and BMI). Medical and anesthetic history (diabetes mellitus, obesity, depression and failed peripheral anesthesia), guided block (ultrasound, neurostimulation and dual stimulation); local anesthetic used (volume, concentration and dose), complementary perineural medications (epinephrine, dexamethasone and others), operator (general anesthesiologist, – GA; Regional anesthesiologist – RA; resident supervised by GA; and resident supervised by RA). RA were the anesthesiologist with a second specialty in Regional Anesthesia endorsed by a university and completed at least 12 months-training (three anesthesiologists for the study period). Residents were classified as with/without regional anesthesia internship (before and after the mandatory two-month training as part of their education as anesthesiologists). These variables were chosen based on their potential association to failure.

The criteria for our definition of failure and potentially-associated variables were pooled in the Microsoft Excel 2010 program (license HUSI). The sample size calculation was made based on a pilot recruitment of patients intervened on April 2011 (HUSI, unpublished). 22 brachial plexus block procedures were recorded during this time period, as the single anesthetic technique for the surgical procedures, including 5 failures as per our definition (all as a result of the initial administration of general anesthesia after the surgical incision {first criterion}). Based on this frequency of procedures and failures, it was estimated that data had to be collected for at least 14 months to identify differences of 20% beginning with outcomes (failed block) between the most experienced and trained group (RA and resident supervised by RA) and the less experienced and trained group (GA and resident with no internship supervised by GA or RA); alpha error 0.05 and 80% power. This calculation was done using Epidat 3.1 software (downloaded free of charge – PAHO). However, it may be possible that this month was not necessarily representative of the number of upper limb surgical procedures at the HUSI so the timeframe was extended to 24 months. The associations were measured with Epidat 3.1 (differences in frequency of failures for dichotomous comparisons) and multivariate analysis-based logistical regression was planned for all variables and univariate for statistically significant risk factors, SSPS (version 19) software; percentage differences were calculated, Chi square tests, confidence intervals and p-value analyses to stablish statistically significant differences.

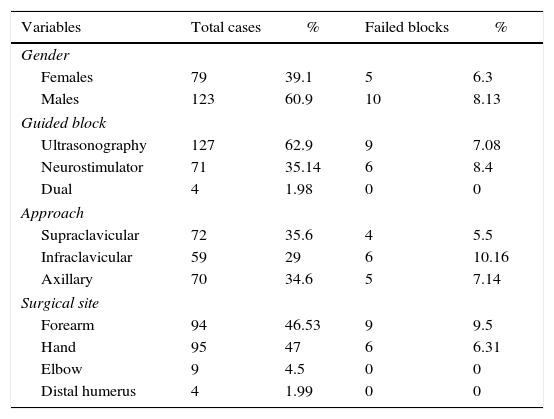

ResultsInformation was collected from 202 patients. The mean age was 46 years old; most patients were males (60.9%). There were no records reporting history of anxiety, depression, or previous failed block. 5% of the patients presented with arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus or obesity. The diagnosis of obesity was based on the medical history and could not be inferred from anthropometric measurements because these were not systematically recorded in the medical records.

All blockades were administered for orthopedic surgery, mostly of the forearm (47%), and hand (45%), followed by elbow (4%) and distal humerus (2%). (Table 1)

General description of population and failed block cases.

| Variables | Total cases | % | Failed blocks | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Females | 79 | 39.1 | 5 | 6.3 |

| Males | 123 | 60.9 | 10 | 8.13 |

| Guided block | ||||

| Ultrasonography | 127 | 62.9 | 9 | 7.08 |

| Neurostimulator | 71 | 35.14 | 6 | 8.4 |

| Dual | 4 | 1.98 | 0 | 0 |

| Approach | ||||

| Supraclavicular | 72 | 35.6 | 4 | 5.5 |

| Infraclavicular | 59 | 29 | 6 | 10.16 |

| Axillary | 70 | 34.6 | 5 | 7.14 |

| Surgical site | ||||

| Forearm | 94 | 46.53 | 9 | 9.5 |

| Hand | 95 | 47 | 6 | 6.31 |

| Elbow | 9 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Distal humerus | 4 | 1.99 | 0 | 0 |

Source: Authors.

The most frequent approaches were axillary and supreaclavicular. 62.9% were ultrasound guided; 35.14% were neurostimulator guided and 1.98% used a dual technique. 1% or 2% lidocaine and 0.5 bupivacaíne % (combined) were used in 95% of blocks. Most blocks were administered or supervised by GA (119 cases {60%}). Despite being a training institution, in 70% of the cases the operator was not a resident; 20% and 50% were RA and GA, respectively.

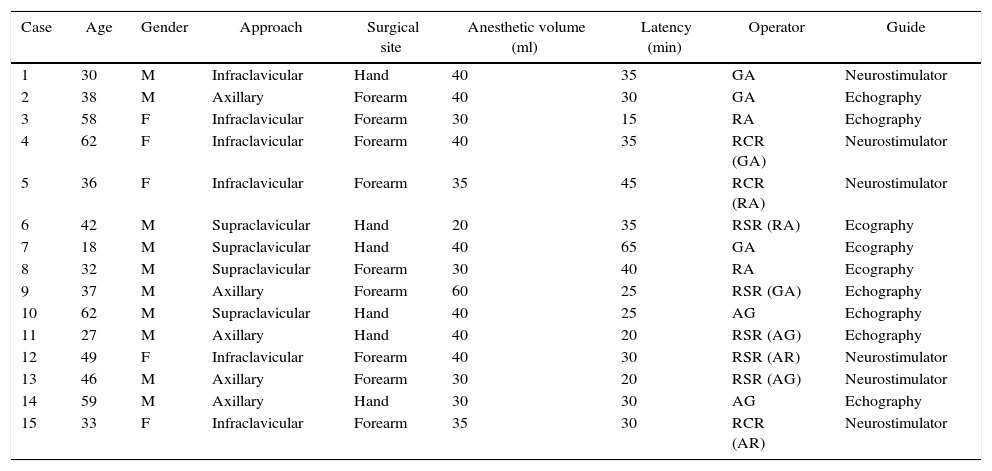

7.4% of failed blocks (Table 2) were all due to the start of general anesthesia following the surgical incision (first criterion). Of these, 6% of failures were among females and 8% among males. The average age of patients with failed blocks was 41 years (age range 18–62 years) and there were not comorbidities present. 60% of failures occurred in blocks with ultrasound guidance, 40% in blocks guided by nerve stimulator and none used a dual technique (among the neurostimulation and ultrasound-guided blocks, 8.5% and 7% were failed, respectively) (Table 1).

Failed brachial plexus blocks.

| Case | Age | Gender | Approach | Surgical site | Anesthetic volume (ml) | Latency (min) | Operator | Guide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | M | Infraclavicular | Hand | 40 | 35 | GA | Neurostimulator |

| 2 | 38 | M | Axillary | Forearm | 40 | 30 | GA | Echography |

| 3 | 58 | F | Infraclavicular | Forearm | 30 | 15 | RA | Echography |

| 4 | 62 | F | Infraclavicular | Forearm | 40 | 35 | RCR (GA) | Neurostimulator |

| 5 | 36 | F | Infraclavicular | Forearm | 35 | 45 | RCR (RA) | Neurostimulator |

| 6 | 42 | M | Supraclavicular | Hand | 20 | 35 | RSR (RA) | Ecography |

| 7 | 18 | M | Supraclavicular | Hand | 40 | 65 | GA | Ecography |

| 8 | 32 | M | Supraclavicular | Forearm | 30 | 40 | RA | Ecography |

| 9 | 37 | M | Axillary | Forearm | 60 | 25 | RSR (GA) | Echography |

| 10 | 62 | M | Supraclavicular | Hand | 40 | 25 | AG | Echography |

| 11 | 27 | M | Axillary | Hand | 40 | 20 | RSR (AG) | Echography |

| 12 | 49 | F | Infraclavicular | Forearm | 40 | 30 | RSR (AR) | Neurostimulator |

| 13 | 46 | M | Axillary | Forearm | 30 | 20 | RSR (AG) | Neurostimulator |

| 14 | 59 | M | Axillary | Hand | 30 | 30 | AG | Echography |

| 15 | 33 | F | Infraclavicular | Forearm | 35 | 30 | RCR (AR) | Neurostimulator |

M, male; F, female; GA, general anesthesiologist; RA, regional anesthesiologist; RSR, resident no regional anesthesia training; RCR, resident with training.

Source: Authors.

Failed blocks had the following approach distribution: 40% infraclavicular, 33% axillary and 27% supraclavicular. Out of the infraclavicular blocks, 10% failed of which 83% were neurostimulation-guided; no operator differences were identified. 6% of axillary blocks failed, of which 80% were ultrasound guided and 20% were neurostimulation guided. All failed axillary blocks were administered by GA or resident with no regional anesthesia training. 5% of the supraclavicular blocks failed, all were ultrasound-guided and with no operator differences identified.

None of the factors potentially associated with failure had a statistically significant relationship with the outcome measured for dichotomous comparisons. The logistic regression was not statically significant either for any of the variables.

DiscussionThe clinical definition of brachial plexus regional anesthesia failure for upper extremity surgery may exhibit some variability. Finlayson et al. propose increasingly objective score-based systems to determine the latency of successful sensitive and motor blockade of each peripheral nerve, defining as a failure the inability to reach a minimum score in the sensorial domains and in the sensitive and motor combination within 30min,26 or whenever similar criteria to those of our definition of failure during surgery are presented. The use of this extended, more sensitive failure definition, not systematically registered in the HUSI medical records, may play an important role, not just in research, but in our daily clinical practice, with early identification of failures prior to the start of surgery, avoiding any injuries to the patient and interventions that may be perceived as improvised and stressing for the patient.

Our failure frequency is similar to other series simultaneously collected and reported in the literature;27,28 this may translate into an under-registration of failures in our environment, that may lead to increased registry biases.

Our sample size was based on the association of a successful or failed block and operator expertise, based on the frequency of regional procedures and failure in a pilot trial described under materials and methods (not published). The only variable showing a potentially causal relationship with outcome was gender; however, a logistic regression analysis, showed no statistically significant association with this or a different variable analyzed – probably related to the low frequency of failures in our sample. The trends described in the results section are supported by trends in the local anesthetic practices and may represent confounding factors not necessarily associated with true failure associated factors. For instance, the fact that all failed supraclavicular blocks were ultrasound-guided represents a constant in the guidelines for supraclavicular blocks at the HUSI, where none of these blocks is administered via anatomical landmarks or neurostimulation and very few with the dual technique. Likewise, the fact that failed axillary blocks were administered by a GA or a resident who has not done a rotation in regional anesthesia may be explained because less experienced practitioners prefer this approach due to the lower risk of involving structures associated with severe complications (pleural injury, phrenic nerve block, and primary neuronal injury due to the presence of less myelinated fibers). In conclusion, the low frequency of failures in the sample analyzed makes it impossible to develop any solid conclusions or associations from the clinical and statistical point of view.

The determining factors of a successful block are controversial.29 It is thought that in order to improve the probability of success of a peripheral nerve block, it is necessary to do a proper identification of the nerve or plexus, to place the needle close to the nerve, and be able to fully encircle the nerve with local anesthetic.12,30 Direct vision of the nerve and other adjacent structures ensures improved distribution of the local anesthetic, shortens the time to perform the block, reduces the volume of anesthetic agent, reduces the risk of any vascular or neural lesion and the probability of toxicity resulting from local anesthetic agents and the detection of anatomic variants that may impair the effectiveness of the block.29,31,32 Ultrasound guidance has shown to improve clinical outcomes22,33 but this trial failed to show any improved outcomes in terms of effectiveness (reductions of failures); this may be explained by the low frequency of failures, in addition to the fact that neurostimulation effectiveness is quite high in experienced hands.34 Neurosmulation-assisted blocks are associated with decreased patient satisfaction. This is important for trauma patients since the electrical stimulus leads to muscle contraction and movement may cause discomfort and paint to the patient.35 Due to the observational, historical, and record-based nature of the trial, patient satisfaction or pain during the administration of the block were not evaluated; however, these are important outcomes from the patient's perspective and may potentially rise the frequency of failures.

Though there were very few cases using the dual technique, there were no failures with this technique. The literature recommends its use exceptionally in regional anesthesia resident and training programs, since it reduces the time of administration of the block, the number of punctures needs and the number of complications.30

Our study identified volumes of local anesthetic above the minimum effective volumes reported in other series36,37 and guide methods. However, when comparing the volumes by subgroups, based on the guides used, these were smaller in the ultrasound-guided blocks versus neurostimulation, (mean volume 33.3ml (95% CI 31.5–35ml) versus 35.1ml (95% CI 33.7–36.4ml), respectively), consistent with the reports from other authors.38

ConclusionsBrachial plexus block failure-associated factors are multifactorial and multidimensional. These may depend on the patient, the operator, the guide, the approach selected, medications, dose, concentration or volume selected. Failure frequency depends on the definition used and the way it is measured. Our study evidences the difficulties to determine these factors associated with failures of a highly effective procedure in the current clinical practice.

It is recommended to improve the quality of anesthesiology records and data bases to determine associations measured with less probability of biases, quantifiable and objective of the interventions in patients undergoing procedures under anesthesia and specifically under regional anesthesia in order to estimate the pre-surgical risk of failure with these techniques and establish strategies focused on risk groups that improve the effectiveness of peripheral regional anesthesia.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors must have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence must be in possession of this document.

FinancingThe authors did not receive sponsorship to carry out this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Moreno-Martínez DA, Perea-Bello AH, Díaz-Bohada JL, García-Rodriguez DM, Echeverri-Mallarino V, Valencia-Peña MJ, et al. Factores asociados con anestesia regional fallida de plexo braquial para cirugía de extremidad superior. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2016;44:292–298.