Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) establish symbiosis between most vascular plant roots, and play a key role in facilitating nutrient uptake1; they have been applied as microbial inoculants in low-input farming sustainable systems. In this context, other microbial inoculants are used as biocontrol agents of plant-pathogenic fungi, the most common in commercial inoculants being Trichoderma harzianum, Gliocladium virens and Bacillus subtilis.2,3 Those applications have shown beneficial effects on plant health and productivity. However, the understanding of the interactions between biological control agents and AMF requires special attention because of the possibility that these fungal antagonists could also interfere with AMF activity.

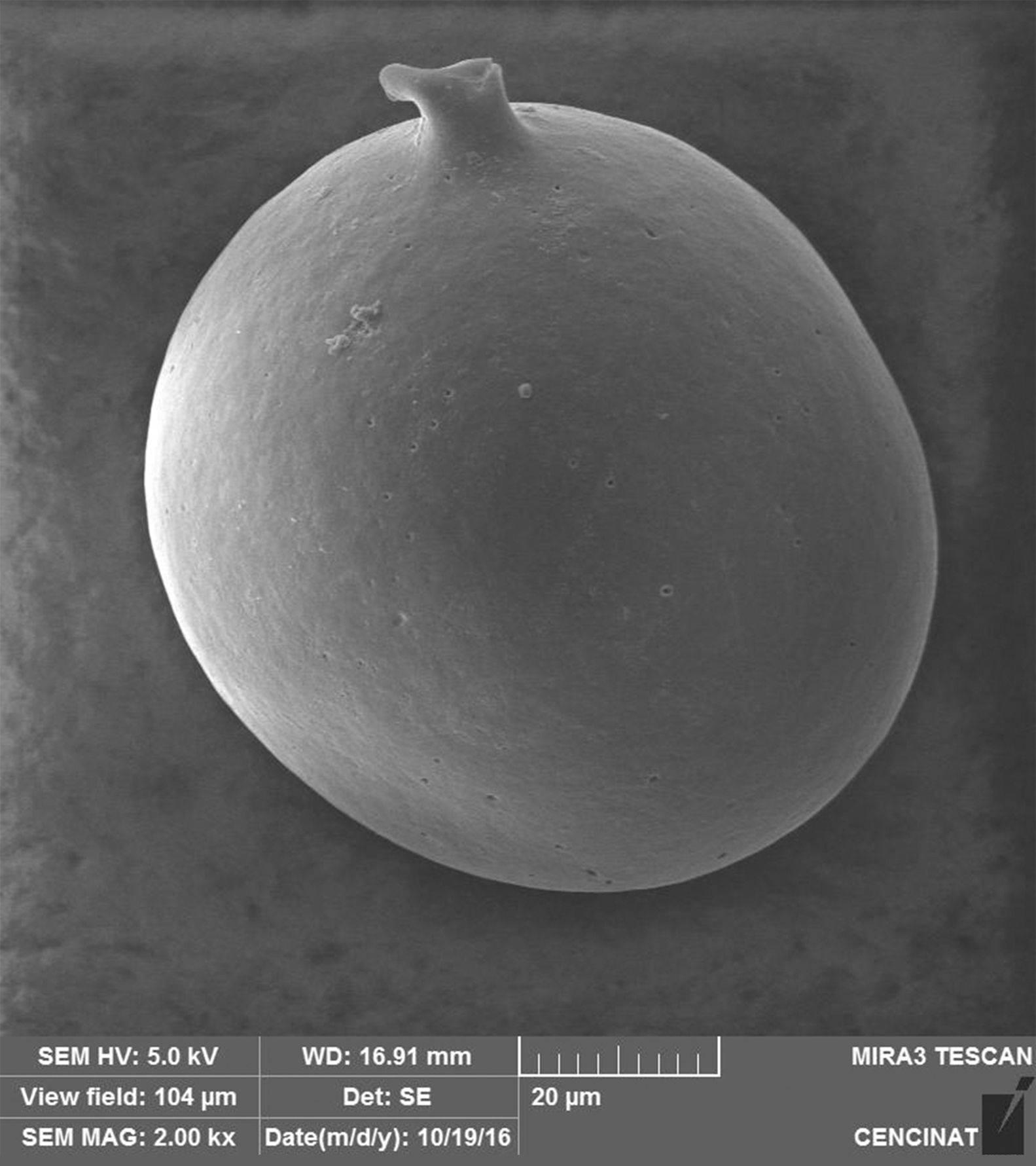

Here we performed scanning electron microscopic (SEM) observations of Acaulospora colombiana spores exposed to T. harzianum, G. virens and B. subtilis, after 30 days of interaction under in vitro conditions.

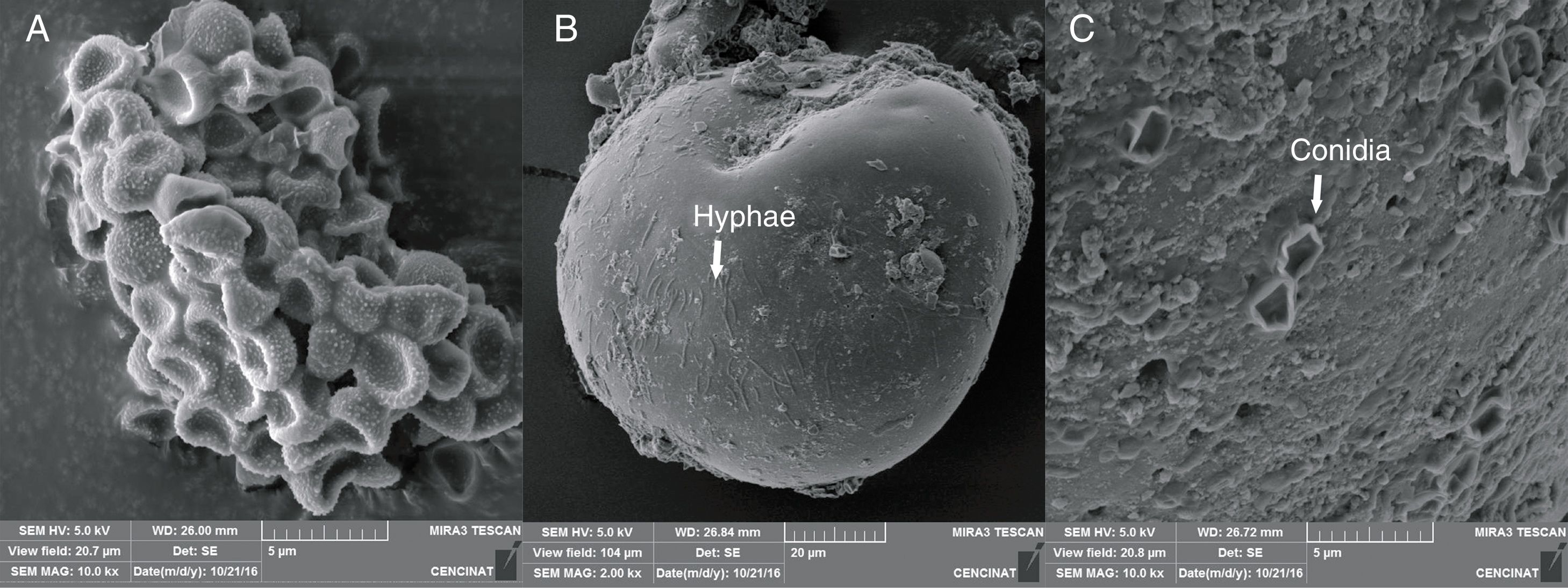

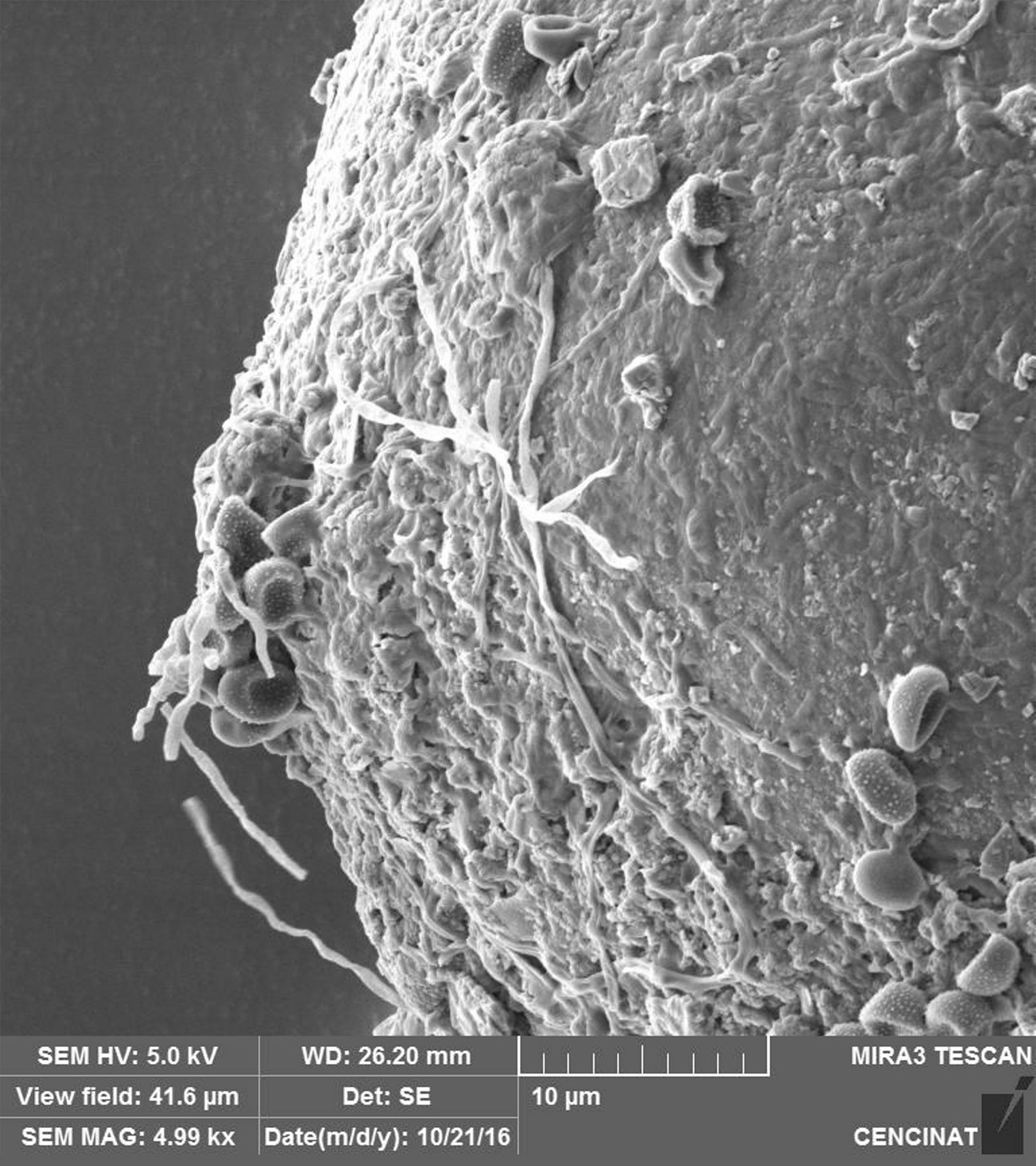

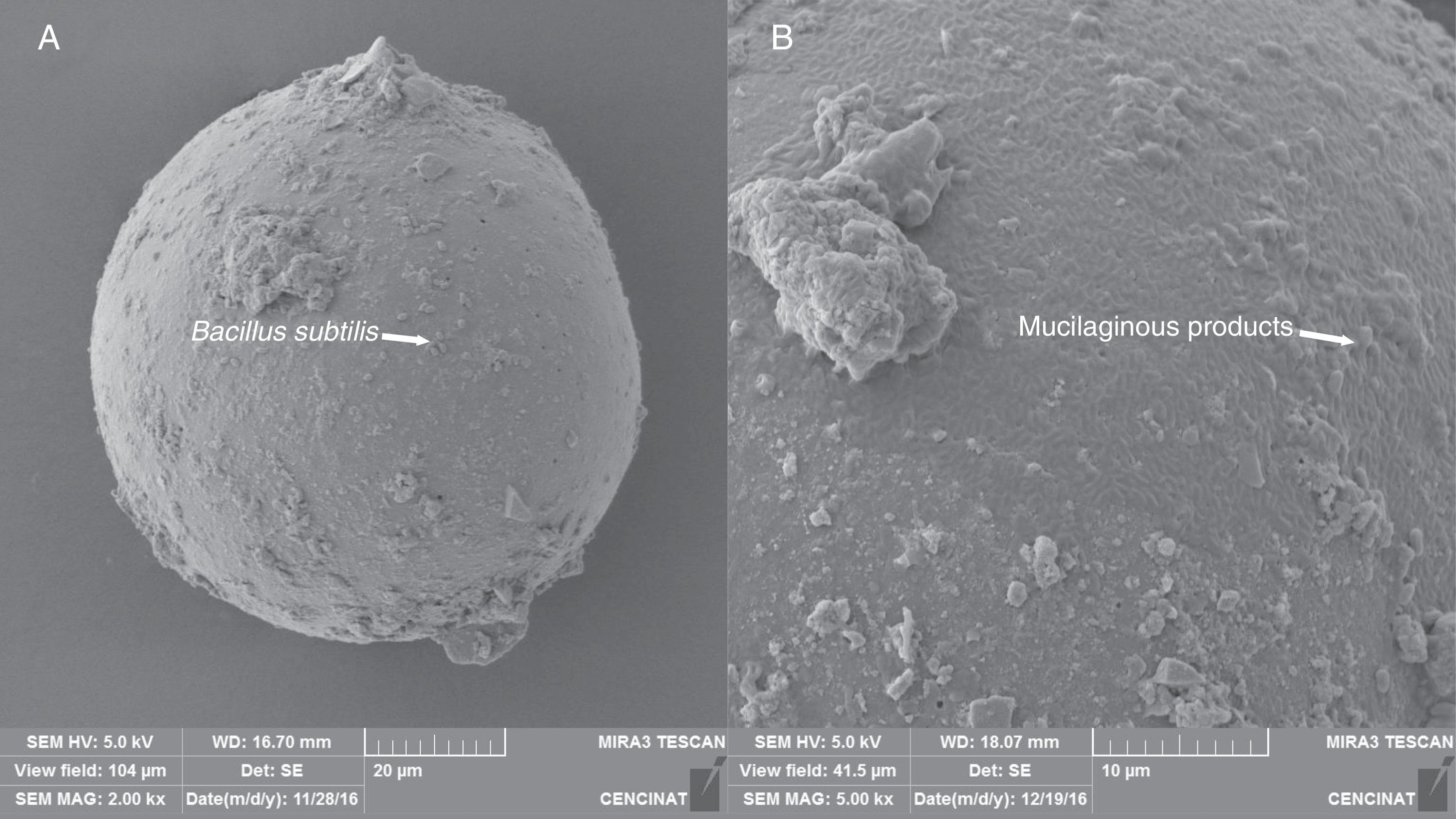

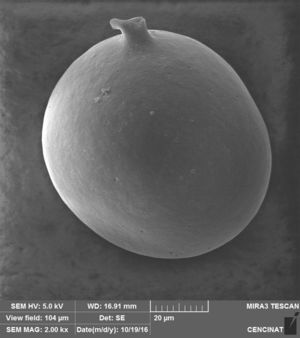

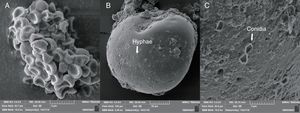

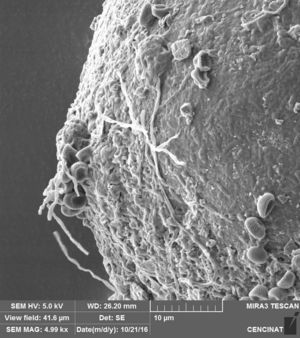

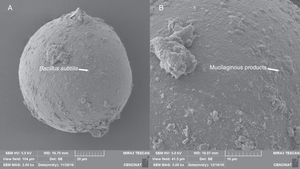

The micrographs revealed that the outer hyaline spore layer was strongly eroded and that the spore surface was covered with mucilaginous products. Moreover, the outer hyaline layer showed an early stage of degradation in all the interactions of biocontrol agents and AMF in contrast with the control (Fig. 1). T. harzianum and G. virens hyphae grew alongside the spore adhered to the laminated layer or embedded in the sloughing hyaline layer (Figs. 2 and 3). A. colombiana spore wall was covered with bacterial bacillus-shaped cells of different sizes (Fig. 4A). Moreover, rough and mucilaginous material covered 50% of the spore surface (Fig. 4B). Decaying material complicated the observation of bacterial cells because they appeared to be covered with their own mucilage.

Scanning electron micrographs of surface of A. colombiana spores. (A) B. subtilis adhering to the surface of the laminated layer of the spore surface after 15 days of inoculation. (B) Mucilaginous outer hyaline layer starting to “peel off” and being replaced by mucilaginous products (arrow).

In our study, evidence of fungal and bacterial AMF spore saprophytic activity was suggested by SEM observations. An understanding of these effects is essential for obtaining the maximum benefit for plant growth and health in the context of agroecosystem sustainability.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

We are grateful to Ing. Andrea Vaca (Nanomaterials Characterization Laboratory, Center of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology – CENCINAT) for providing technical support to take the SEM microgrhaps.