The ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), although uncommon, is an important complication of assisted reproduction because of its morbidity and possible lethal outcome.

ObjectiveTo verify the incidence of OHSS in public service of assisted reproduction and review the literature.

MethodA descriptive retrospective study of patients enrolled in the Assisted Reproduction Laboratory of Hospital Pérola Byington who had 15 or more oocytes retrieved during controlled ovarian stimulation cycle, period 2010-2012. A literature search was conducted in the databases Medline, Scopus and SciELO including articles indexed between 2010 and 2013.

ResultsOHSS was observed in 17 cycles (1.9%) of 857 performed. The mean age was 33.2 years, with a mean of 21.6 oocytes retrieved and 11.5 mature oocytes. Hospitalization and ascites puncture was required in five cases. There was no fatal outcome. The literature suggests that methods used to predict the ovarian response help to prevent OHSS, as antral follicle count, serum estradiol and anti-mullerian hormone. Evidence indicates that stimulation with GnRH antagonist and triggering with GnRH agonist, with or without vitrification of embryos are safe strategies for patients with high risk for OHSS.

ConclusionThe incidence of OHSS was found to be within the range of literature. Although none of the approaches for the prevention of OHSS is fully effective, the majority demonstrates a decreasing incidence in high-risk patients.

A Síndrome de Hiperestímulo Ovariano (SHO), apesar de pouco frequente, é complicação importante na reprodução assistida devido sua morbidade e possibilidade de desfecho letal.

ObjetivoVerificar a incidência da SHO em serviço público de reprodução assistida e revisar a literatura.

MétodoEstudo descritivo retrospectivo com prontuários de pacientes matriculadas no Laboratório de Reprodução Assistida do Hospital Pérola Byington de 2010 a 2012, que apresentaram 15 ou mais oócitos aspirados durante ciclo de estimulação ovariana controlada. Consulta nas bases de dados do Medline, Scopus e Scielo incluindo artigos indexados entre 2010 e 2013.

ResultadosSHO foi verificada em 17 ciclos (1,9%) dos 857 realizados. A média etária foi de 33,2 anos, com média de 21,6 oócitos aspirados e 11,5 oócitos maduros. Internação foi necessária em cinco casos. Não houve desfecho fatal. A literatura aponta que métodos empregados para prever a resposta ovariana auxiliam na prevenção da SHO, como contagem de folículos antrais, dosagem de estradiol e hormônio anti-mulleriano. Evidências indicam que a estimulação com antagonista do GnRH e desencadeamento da ovulação com agonista do GnRH, com ou sem vitrificação de embriões, como estratégias seguras para pacientes com alto risco para SHO.

ConclusãoA incidência da SHO mostrou-se dentro da variação da literatura. Embora nenhuma das abordagens de prevenção da SHO seja totalmente eficaz, a maioria demonstra diminuição da incidência em pacientes de alto risco.

The ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) remains a feared complication, both the patient and the physician using Assisted Reproduction Techniques (ART). The OHSS presents symptoms from mild to severe forms of abdominal discomfort leading to hospitalization, and, in some cases, including fatal outcome.1

The incidence of clinically significant OHSS is 2 to 3%. However, milder forms may develop up to 30% of patients undergoing ART.2 The syndrome affects approximately 6,020 patients per year in the United States and Europe, with risk of death estimated between 1:450,000 and 1:500,000.3,4

The pathophysiology of OHSS is complex and not yet fully determined. However, it involves increased capillary permeability mesothelial surface of the ovaries and extravasation of protein-rich fluid in the third space.5 Clinical manifestations reflect the extent of leakage and hemoconcentration resulting from intravascular volume depletion.

Signs and symptoms vary according to the severity of the syndrome. It might occur only mild discomfort and abdominal distension due to the increase in the volume of one or both ovaries. In more severe forms it can be observed the formation of ascites in varying degrees, pleural effusion and oliguria, renal failure and death may occur as a result of hemoconcentration and reduced perfusion of other organs such as kidneys, heart and brain.6,7

Two types of OHSS are identified. The early onset one, which is associated with the response after ovarian stimulation, is usually self-limited if no pregnancy occurs. The delayed form develops in ten days or more after conception, and in many cases require hospitalization.8,9

Several studies indicate that the development of OHSS is mediated by the presence of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), exogenous or endogenous.5 The administration of hCG would lead to an increased vascular permeability, mediated by the receptors of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) present in the theca-cells and granulosa.5,10,11 Prostaglandins, inhibin, mediators of the inflammatory system and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system are also factors involved in the etiology of OHSS.5,12

Considering its importance, the objective is to determine the incidence of OHSS in a public service of assisted reproduction and review relevant publications on the topic with an emphasis on prevention.

MethodA retrospective descriptive study in which they were consulted the medical records of all patients regularly enrolled in the Assisted Reproduction Laboratory of Hospital Pérola Byington who had 15 or more oocytes aspirated during controlled ovarian stimulation cycle in the period 2010-2012. Data of the patients were recorded: age, infertility factor, type and number of units of FSH, type of agonist/antagonist employed, type of medication to trigger ovulation, number of oocytes aspirated, number of mature oocytes, fertilization rate; technique of fertilization, embryo transfer, days of hospitalization, ascites puncture; occurrence of pregnancy and mode of treatment.

For the literature review were consulted the databases Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (Medline) and Pubmed, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) and SCOPUS. The survey covered the period from 2010 to 2012 and used DeCS/MeSH with the syntax “[Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome] AND [Fertilization In Vitro].” The search result considered original articles, systematic reviews, explanatory reviews that address OHSS in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization techniques.

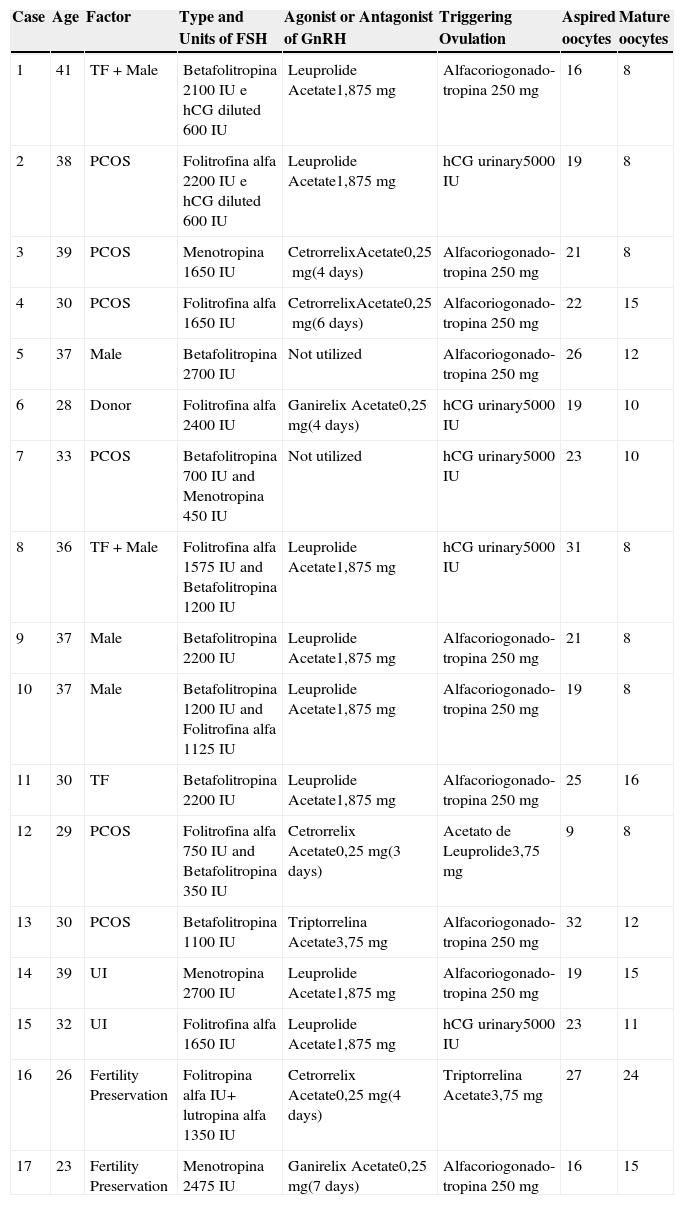

ResultsThe incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) was 1.9%. It was diagnosed in 15 patients, two of which showed the condition in more than one cycle, with a total of 17 cycles with OHSS from 857 cycles performed. The age ranged 23-41 years, mean 33.2 years. Between 9 and 32 oocytes were aspirated in 17 cases, averaging 21.6 oocytes aspirated and 11.5 mature oocytes (Table 1).

Assisted reproduction technique employed and oocyte production in cases of Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS), Hospital Pérola Byington, 2010-2012.

| Case | Age | Factor | Type and Units of FSH | Agonist or Antagonist of GnRH | Triggering Ovulation | Aspired oocytes | Mature oocytes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41 | TF+Male | Betafolitropina 2100 IU e hCG diluted 600 IU | Leuprolide Acetate1,875mg | Alfacoriogonado-tropina 250mg | 16 | 8 |

| 2 | 38 | PCOS | Folitrofina alfa 2200 IU e hCG diluted 600 IU | Leuprolide Acetate1,875mg | hCG urinary5000 IU | 19 | 8 |

| 3 | 39 | PCOS | Menotropina 1650 IU | CetrorrelixAcetate0,25mg(4 days) | Alfacoriogonado-tropina 250mg | 21 | 8 |

| 4 | 30 | PCOS | Folitrofina alfa 1650 IU | CetrorrelixAcetate0,25mg(6 days) | Alfacoriogonado-tropina 250mg | 22 | 15 |

| 5 | 37 | Male | Betafolitropina 2700 IU | Not utilized | Alfacoriogonado-tropina 250mg | 26 | 12 |

| 6 | 28 | Donor | Folitrofina alfa 2400 IU | Ganirelix Acetate0,25mg(4 days) | hCG urinary5000 IU | 19 | 10 |

| 7 | 33 | PCOS | Betafolitropina 700 IU and Menotropina 450 IU | Not utilized | hCG urinary5000 IU | 23 | 10 |

| 8 | 36 | TF+Male | Folitrofina alfa 1575 IU and Betafolitropina 1200 IU | Leuprolide Acetate1,875mg | hCG urinary5000 IU | 31 | 8 |

| 9 | 37 | Male | Betafolitropina 2200 IU | Leuprolide Acetate1,875mg | Alfacoriogonado-tropina 250mg | 21 | 8 |

| 10 | 37 | Male | Betafolitropina 1200 IU and Folitrofina alfa 1125 IU | Leuprolide Acetate1,875mg | Alfacoriogonado-tropina 250mg | 19 | 8 |

| 11 | 30 | TF | Betafolitropina 2200 IU | Leuprolide Acetate1,875mg | Alfacoriogonado-tropina 250mg | 25 | 16 |

| 12 | 29 | PCOS | Folitrofina alfa 750 IU and Betafolitropina 350 IU | Cetrorrelix Acetate0,25mg(3 days) | Acetato de Leuprolide3,75mg | 9 | 8 |

| 13 | 30 | PCOS | Betafolitropina 1100 IU | Triptorrelina Acetate3,75mg | Alfacoriogonado-tropina 250mg | 32 | 12 |

| 14 | 39 | UI | Menotropina 2700 IU | Leuprolide Acetate1,875mg | Alfacoriogonado-tropina 250mg | 19 | 15 |

| 15 | 32 | UI | Folitrofina alfa 1650 IU | Leuprolide Acetate1,875mg | hCG urinary5000 IU | 23 | 11 |

| 16 | 26 | Fertility Preservation | Folitropina alfa IU+ lutropina alfa 1350 IU | Cetrorrelix Acetate0,25mg(4 days) | Triptorrelina Acetate3,75mg | 27 | 24 |

| 17 | 23 | Fertility Preservation | Menotropina 2475 IU | Ganirelix Acetate0,25mg(7 days) | Alfacoriogonado-tropina 250mg | 16 | 15 |

PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; UI, unexplained infertility; TF, tubal factor; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; IU, internacional unit; mg, milligram.

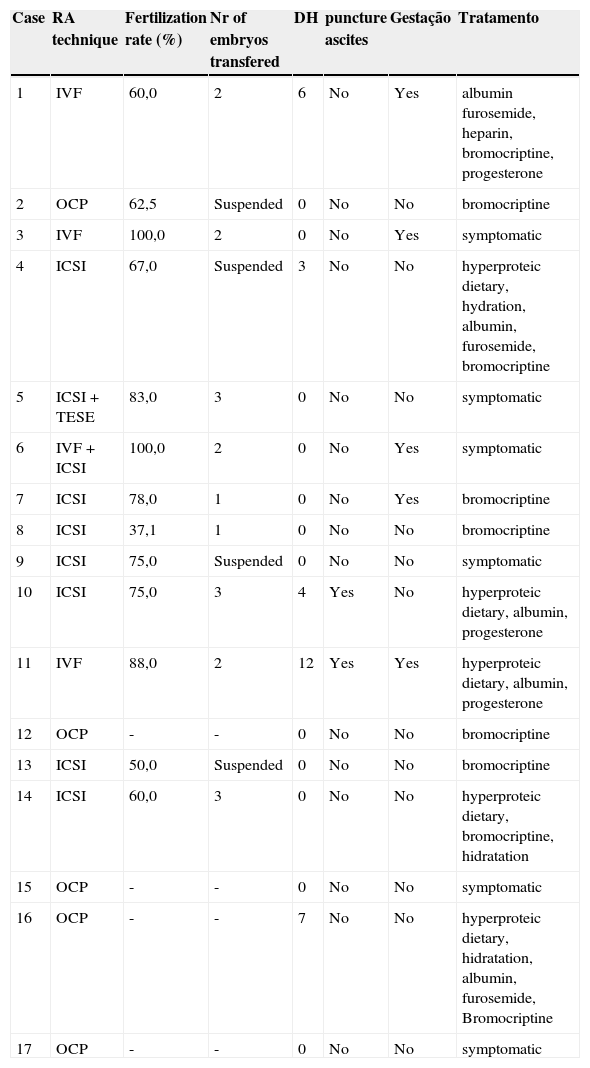

The hospitalization for treatment of OHSS was required in five cases, with an average of 6.4 days. Ascite puncture was performed in five cases (Table 2). There was no fatal outcome in the studied cases of OHSS.

Results of assisted reproduction technique employed, days of hospitalization and treatment of cases of Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS), Hospital Pérola Byington, 2010 - 2012.

| Case | RA technique | Fertilization rate (%) | Nr of embryos transfered | DH | puncture ascites | Gestação | Tratamento |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IVF | 60,0 | 2 | 6 | No | Yes | albumin furosemide, heparin, bromocriptine, progesterone |

| 2 | OCP | 62,5 | Suspended | 0 | No | No | bromocriptine |

| 3 | IVF | 100,0 | 2 | 0 | No | Yes | symptomatic |

| 4 | ICSI | 67,0 | Suspended | 3 | No | No | hyperproteic dietary, hydration, albumin, furosemide, bromocriptine |

| 5 | ICSI+TESE | 83,0 | 3 | 0 | No | No | symptomatic |

| 6 | IVF+ICSI | 100,0 | 2 | 0 | No | Yes | symptomatic |

| 7 | ICSI | 78,0 | 1 | 0 | No | Yes | bromocriptine |

| 8 | ICSI | 37,1 | 1 | 0 | No | No | bromocriptine |

| 9 | ICSI | 75,0 | Suspended | 0 | No | No | symptomatic |

| 10 | ICSI | 75,0 | 3 | 4 | Yes | No | hyperproteic dietary, albumin, progesterone |

| 11 | IVF | 88,0 | 2 | 12 | Yes | Yes | hyperproteic dietary, albumin, progesterone |

| 12 | OCP | - | - | 0 | No | No | bromocriptine |

| 13 | ICSI | 50,0 | Suspended | 0 | No | No | bromocriptine |

| 14 | ICSI | 60,0 | 3 | 0 | No | No | hyperproteic dietary, bromocriptine, hidratation |

| 15 | OCP | - | - | 0 | No | No | symptomatic |

| 16 | OCP | - | - | 7 | No | No | hyperproteic dietary, hidratation, albumin, furosemide, Bromocriptine |

| 17 | OCP | - | - | 0 | No | No | symptomatic |

IVF, in vitro fertilization; TESE, testicular sperm extraction; OCP, oocyte cryopreservation; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm inject; DH, days of hospitalization.

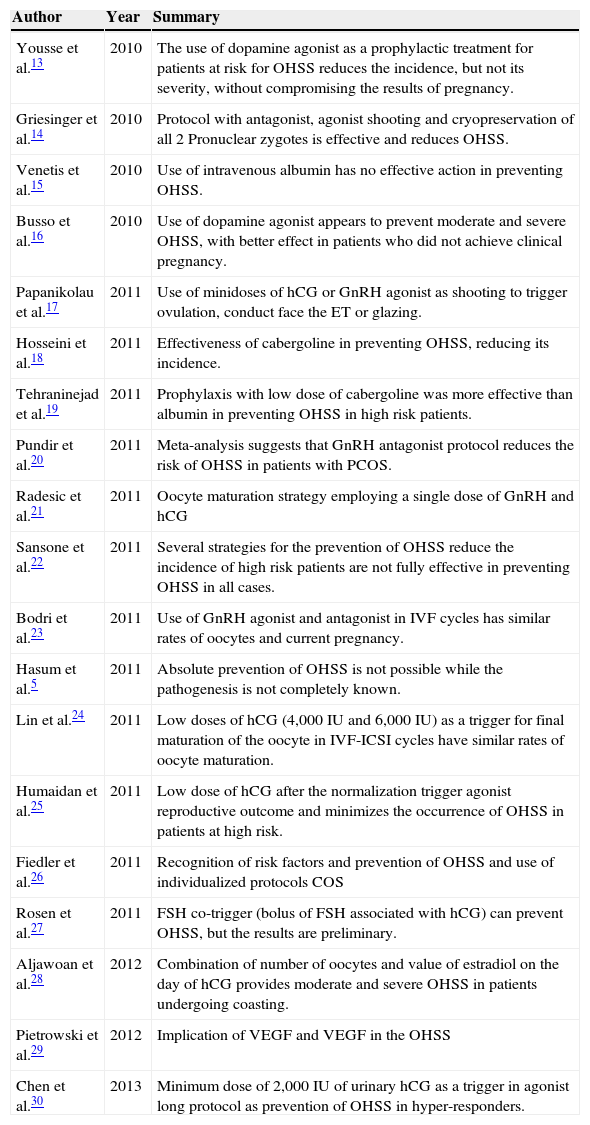

We have identified 308 articles indexed to descriptors DeCS/MeSH in the four databases consulted. After analyzing the manuscripts, 20 publications were selected between clinical trials and systematic reviews (Table 3).

Summary of publications on the Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS).

| Author | Year | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Yousse et al.13 | 2010 | The use of dopamine agonist as a prophylactic treatment for patients at risk for OHSS reduces the incidence, but not its severity, without compromising the results of pregnancy. |

| Griesinger et al.14 | 2010 | Protocol with antagonist, agonist shooting and cryopreservation of all 2 Pronuclear zygotes is effective and reduces OHSS. |

| Venetis et al.15 | 2010 | Use of intravenous albumin has no effective action in preventing OHSS. |

| Busso et al.16 | 2010 | Use of dopamine agonist appears to prevent moderate and severe OHSS, with better effect in patients who did not achieve clinical pregnancy. |

| Papanikolau et al.17 | 2011 | Use of minidoses of hCG or GnRH agonist as shooting to trigger ovulation, conduct face the ET or glazing. |

| Hosseini et al.18 | 2011 | Effectiveness of cabergoline in preventing OHSS, reducing its incidence. |

| Tehraninejad et al.19 | 2011 | Prophylaxis with low dose of cabergoline was more effective than albumin in preventing OHSS in high risk patients. |

| Pundir et al.20 | 2011 | Meta-analysis suggests that GnRH antagonist protocol reduces the risk of OHSS in patients with PCOS. |

| Radesic et al.21 | 2011 | Oocyte maturation strategy employing a single dose of GnRH and hCG |

| Sansone et al.22 | 2011 | Several strategies for the prevention of OHSS reduce the incidence of high risk patients are not fully effective in preventing OHSS in all cases. |

| Bodri et al.23 | 2011 | Use of GnRH agonist and antagonist in IVF cycles has similar rates of oocytes and current pregnancy. |

| Hasum et al.5 | 2011 | Absolute prevention of OHSS is not possible while the pathogenesis is not completely known. |

| Lin et al.24 | 2011 | Low doses of hCG (4,000 IU and 6,000 IU) as a trigger for final maturation of the oocyte in IVF-ICSI cycles have similar rates of oocyte maturation. |

| Humaidan et al.25 | 2011 | Low dose of hCG after the normalization trigger agonist reproductive outcome and minimizes the occurrence of OHSS in patients at high risk. |

| Fiedler et al.26 | 2011 | Recognition of risk factors and prevention of OHSS and use of individualized protocols COS |

| Rosen et al.27 | 2011 | FSH co-trigger (bolus of FSH associated with hCG) can prevent OHSS, but the results are preliminary. |

| Aljawoan et al.28 | 2012 | Combination of number of oocytes and value of estradiol on the day of hCG provides moderate and severe OHSS in patients undergoing coasting. |

| Pietrowski et al.29 | 2012 | Implication of VEGF and VEGF in the OHSS |

| Chen et al.30 | 2013 | Minimum dose of 2,000 IU of urinary hCG as a trigger in agonist long protocol as prevention of OHSS in hyper-responders. |

OHSS, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; IU, international unit; GnRH, gonadotrofin-releasing hormone; ET, embryo transfer ; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; FIV, in vitro fertilization; COS, controlled ovarian stimulation; VGEF, vascular endothelial growth factor; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone.

The incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) of 1.9% found in this study proved to be convergent with what has been verified in other publications. The same occurred for the characterization of patients with OHSS and the assisted reproduction techniques employed.

The prophylaxis of OHSS is a multistep process, being critical for the primary prevention to recognize the risk factors and individualize controlled ovarian stimulation (COS).31,32 It is necessary to identify the population at risk before performing the ovarian stimulation, with the objective of minimizing the doses without any worse reproductive outcome. Finally, it is necessary to take the decision on the trigger ovulation shot and achievement of embryo transfer or not, taking into account the risks posed to the patient and the psychological, social and economic impact of such decision.32

There is a number of well established primary risk factors for developing OHSS, including low age, history of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and personal history of hyper-response in a previous cycle of in vitro fertilization (IVF).12,33,34 Several risk factors and biomarkers for OHSS are known and help to identify patients who require individualized COS. However, the sensitivity and specificity of these markers to predict hyperresponsiveness is variable.35,36

The antral follicle count (AFC) is the number of follicles with 2 to 10mm in diameter. It is a widely used biomarker to predict the response of a patient under COS and determine the risk of OHSS. It can be easily defined by transvaginal ultrasound, ideally in the early follicular phase. A small number of antral follicles is related to the age of the patient and may reflect the ovarian reserve and so predict its answer.36–38

The dosing of Anti-Müllerian Hormone (AMH) before the COS also proved to be a predictive factor for the development of OHSS.5,31 Two randomized prospective cohort studies have shown that basal AMH ≥ 3.5ng/mL can predict the hyper-response with high sensitivity (90.5%) and specificity (81.3%).37,39 Moreover, the dosing of AMH may be a better predictor than age, basal follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), estradiol (E2), and AFC.31,37,40 Serum measurements of E2 on the day of ovulation triggering greater than 4,500pg/mL are considered predictors of risk for OHSS,5,36 although high levels of E2 alone prove to be poor predictors.3,35,36

The presence of PCOS is considered by many authors as the main risk factor related to OHSS5. This is probably due to the increased recruitment of follicles in various stages of maturation, associated with the pathophysiology of PCOS. The PCOS patients who have hyperinsulinemia are more likely to develop syndrome than patients with regular insulin. It is believed that insulin acts as a stimulating factor for early-stage follicles, leading to more mature follicles, which respond more to the presence of luteinizing hormone (LH) and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).5

There is no doubt that the incidence of OHSS is related to the ovarian stimulation regime used.5 Therefore, several protocols have been proposed with the aim of minimizing the risk of developing this syndrome during COS. These strategies include the use of lower doses of FSH, coasting, reduction of the dosage of hCG in the final oocyte maturation, cancellation of the cycle before the hCG, cancellation of embryo transfer and cryopreservation of all viable embryos, and the use of GnRH agonist alternatively to hCG.34

The use of higher doses of FSH increases the risk of hyperstimulation. Therefore, protocols with low-dose (150 IU of FSH), independent of the patient age, using step up or step down, occur with lower risk of OHSS.5 It is observed increased risk of OHSS in cycles of stimulation with urinary gonadotropins in relation to the recombinant.5 The use of GnRH agonist protocols, particularly long protocols, lead to increased incidence of OHSS, probably by stimulation of a large cohort of follicles, combined with the absence of a spontaneous process of luteinization.5

The coasting strategy has been used as a measure of prevention of OHSS and consists of suspending the administration of exogenous gonadotropins and postpone the application of hCG until estradiol levels are below a value considered safe.28 In a recent retrospective study that evaluated 2,948 patients, it was conducted coasting on 327 women who had three follicles ≥ 15mm and E2 ≥ 1635pg/mL, getting OHSS incidence of 10.4%, equivalent to 1.15% of the total cycles IVF/ICSI of that center28. It was observed in this subgroup of patients factors that predict moderate to severe OHSS, as the combination of the number of retrieved oocytes and the amount of E2 on the day of hCG, beside the presence of multiple gestations.28

The trigger with hCG has been used as the gold standard in assisted reproduction techniques, to be clinically approved and highly effective. However, OHSS is still observed despite a lower dose than normally used of 10,000 IU of hCG. The triggering of final oocyte maturation with hCG is the main factor associated with the development of OHSS, and therefore alternatives such as the use of GnRH agonists or recombinant LH can be used to promote the maturation of oocytes and reduce the risk of hyperstimulation.5

Lin et al. (2011), have compared the triggering with 4,000 IU of urinary hCG versus 6,000 IU of hCG, finding an effect of the final oocyte maturation similar in both groups of patients with moderate to intense oocyte response. However, there was no difference in the occurrence of OHSS in both groups and patients who received higher doses of hCG showed higher pregnancy rate (65.3% vs. 35%, p=0.004).24

In an attempt to establish the minimum dose of hCG necessary to promote the final oocyte maturation, Chen et al. (2013) have developed a study in which six women at high risk of developing OHSS received triggering with 2,000 IU of urinary hCG. There were no cases of OHSS with the dose applied, and only one patient had the embryo transfer cancelled and the embryos were frozen with subsequent transfer. In this study, we observed satisfactory reproductive outcomes with the dose used. The average number of oocytes collected was higher than 14, with fertilization rate greater than 77%. Although the sample was small, the results pointed to a tendency to use lower doses of hCG in patients hyper-responders.30

Recent review assessed the association of the FSH dose to trigger with hCG, called “FSH co-trigger” as a strategy to prevent OHSS. The combination of a low dose of FSH to hCG triggering appears to reduce the incidence of OHSS, but the results are still preliminary and there are potential confounding factors.27

It has been shown that the use of GnRH agonist to trigger ovulation, which is only possible with the protocols with antagonist, leads to a lower risk of OHSS and ensures proper oocyte maturation, requiring modification of the luteal phase support.41,42 This luteal support can be accomplished with hCG at low doses, in bolus on the day of the oocytes collection. It is also used intense luteal support with progesterone and estradiol IM or, alternatively, with recombinant LH.25,43

Papanikolaou et al. (2011) compared the use of GnRH agonist with low doses of hCG to trigger ovulation in protocols with both agonist and antagonist. The dose of hCG considered low was 250 mcg of recombinant hCG or 3300-5000 UI of urinary hCG. The trigger with GnRH agonist (Triptorelin 0.2mg, 0.5mg buserelin and leuprolide 1mg) is only possible in a protocol with antagonist. It has been observed that the use of agonist to trigger ovulation minimizes the risk of OHSS, ensuring proper oocyte maturation. The use of hCG, although ensuring the function of the corpus luteum, may cause hyperstimulation, even at low doses.44,45

Griessinger et al. (2010) have studied 51 patients at risk for OHSS, all subjected to stimulation with antagonist protocol and subsequent ovulation triggering with GnRH agonist in combination with cryopreservation of all pronuclear zygotes in phase 2. Only one patient (2%) developed severe OHSS and there was 5% of moderate OHSS, with cumulative live birth rate of 37.3%. This strategy proved to be effective and safe way to reduce the risk of OHSS, maintaining good reproductive outcomes.14

In recent meta-analysis that analyzed 1,024 oocytes donors undergoing ovarian stimulation with antagonist or agonist GnRH were observed rates of oocytes retrieved and clinical pregnancy similar in both groups. There was no difference in the incidence of OHSS between them, although the authors attribute to the limited sample size and the fact that the induction of oocyte maturation end with hCG has been made in most studies reviewed.23

Another possibility for preventing OHSS and its severity reduction is the use of dopamine agonist.46,47 In a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials, the data suggested that cabergoline reduces the risk of moderate and severe OHSS, with no statistically significant difference in the rates of birth, clinical pregnancy or abortion, suggesting that endometrial angiogenesis would not be affected by the use of dopaminergic.46,47 It was observed that the dopamine agonist Cabergoline inactivates the receptor of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF r2) preventing the increase of vascular permeability and justifying its use in the prevention of OHSS.48

A placebo-controlled double-blind randomized multicenter trial has evaluated the use of quinagolide, dopamine agonist not derivative of ergotamin. It was compared using three oral doses of 50, 100 and 200mg/day, beginning on the day of hCG for 17 to 21 days. It has been found that the incidence of moderate to severe early OHSS was significantly lower in the groups that received quinagolide compared with placebo, with a dose-dependent effect. The use of dopamine agonist did not affect reproductive outcome, with a protective effect of OHSS higher in patients who have not become pregnant.11

Systematic reviews and meta-analyzes have evaluated the oral use of cabergoline, at doses of 50, 100 and 200mg, with another study comparing patients who used 20g of intravenous albumin 20% and another group using 0.5mg of cabergoline per day from the first day after oocyte retrieval for 7 to 14 days, reducing the risk of moderate to severe OHSS in high risk patients. It was concluded that the use of cabergoline was superior to the use of intravenous albumin to reduce the risk of OHSS, and that there was no difference in the occurrence of OHSS in patients who received albumin and those who did not receive.9,15,19

Other research indicates that the use of acetylsalicylic acid at the dose of 100mg/day in patients at risk of developing OHSS can be useful in the prevention, because it reduces platelet activation related to the concentration of circulating VEGF and thrombogenic risk that stems from the OHSS.49,50

The current lack of a fast and efficient therapy that promptly resolves electrolyte imbalance of patients makes prevention of OHSS crucial. The cases of mild ovarian hyperstimulation does not require treatment and the moderates require outpatient clinic monitoring and laboratory tests, not forgetting the possibility of progression to the severe form. Severe cases require hospitalization, often in intensive care units.22

Due to the pathophysiology of hemoconcentration resulting from OHSS, there is a hypercoagulability, increasing platelets, fibrinogen and coagulation factors V, VI, VII, and subsequent increased risk of thrombosis. In addition, there are elevated transaminases, hyperkalemia, hyperglycemia by increasing cortisol, inversion of the albumin/globulin and metabolic acidosis. Therapy should therefore emphasize the clinical support in an attempt to avoid the consequent dysfunction syndrome.22 In relation to the ascites, the intravenous administration of 50g of albumin may decrease 800ml of additional vascular fluid in 15minutes, it is recommended a dose of 50 to 100mg a day, considering the half life of albumin from 17 to 20 days.22

ConclusionThe incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) found in the Service of Human Reproduction of Hospital Perola Byington proved to be within the range suggested by the literature. The characterization of patients with OHSS and assisted reproduction techniques employed did not differ from that described in other studies. The literature has evaluated methods of preventing OHSS. Although none of the approaches is so far fully effective, the majority demonstrates a decreasing incidence in high-risk patients.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Research conducted at Hospital Pérola Byington, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.