Suplement “Update and good practice in the contrast media uses”

More infoThe incidence of post-contrast acute kidney injury (PC-AKI) is low with the new low- or iso-osmolar non-ionic iodinated contrast agents. The only proven form of prophylaxis for PC-AKI is hydration, preferably intravenous, although oral hydration is equally effective. In this article we define PC-AKI and its risk factors, propose a prophylaxis protocol and respond to the most common doubts that arise around prophylaxis. We also update the fasting guidelines to be followed prior to contrast testing. In general, fasting of solids is not necessary before injecting iodinated contrast or gadolinium except in tests in which it is necessary to specifically study the upper digestive tract and bile duct. Even in these cases, fasting clear liquids is not required, which is of great help for oral hydration and for reducing the incidence of PC-AKI.

La incidencia de lesión renal aguda postcontraste (LRA-PC) es baja con los nuevos contrastes yodados no iónicos hipo o isosmolares. La única forma de profilaxis probada de LRA-PC es la hidratación, preferentemente intravenosa, aunque la hidratación por vía oral es igualmente efectiva. En este artículo definimos la LRA-PC y sus factores de riesgo, proponemos un protocolo de profilaxis y respondemos a las dudas más frecuentes que aparecen cuando realizamos dicha profilaxis. También actualizamos las pautas de ayunas que deben realizarse antes de las pruebas con contraste. En general no son necesarias las ayunas de sólidos antes de inyectar contraste yodado o gadolinio salvo en pruebas en las que se requiera estudiar específicamente el tracto digestivo superior y la vía biliar. E Incluso en estos casos no se requiere ayunas de líquidos claros, cosa que nos es de gran ayuda para universalizar la hidratación oral y disminuir la incidencia de LRA-PC.

Most of the adverse effects attributed to iodinated contrast media were actually caused by extremely toxic, and therefore discontinued, ionic and high-osmolar iodinated contrast media. Today, we use low- or iso-osmolar non-ionic contrasts which are much safer and cause significantly fewer secondary effects. Nephrotoxicity that is secondary to iodinated contrast administration has been exaggerated for this reason, resulting in the non-approval of iodinated contrasts in patients with renal impairment, even in mild or moderate cases, hindering proper diagnostic and therapeutic management of these patients. In properly hydrated patients, the incidence of nephrotoxicity with the new iodinated contrasts is very low and some authors even claim that such nephrotoxicity does not exist.1–3

In this article, we will review the definition of post-contrast nephrotoxicity and its associated risk factors, along with the existing prophylactic guidelines. We will also propose a prophylactic protocol that we hope will serve as a guide that can be implemented in all radiology centres. Furthermore, we will provide answers to the most frequently asked questions that arise when managing post-contrast nephrotoxicity prophylaxis.

Finally, we will provide an update on whether fasting is necessary before the administration of different contrast media, underscoring the importance of maintaining correct hydration in all patients undergoing iodinated contrast-enhanced studies in order to easily and cheaply avoid dehydration, the biggest risk factor associated with post-contrast nephrotoxicity.4

Nephrotoxicity and iodinated contrast mediaDefinition and risk factors of post-contrast acute kidney injury (PC-AKI)Post-contrast acute kidney injury (PC-AKI) is characterised by an increase of 0.3 mg/dl or more in serum creatinine (sCr) within 48–72 h of administration of iodinated contrast, without any other reasonable explanation.5,6

This new definition places post-contrast acute kidney injury (AKI) within stage 1 of the KDIGO classification of AKI, dispensing with its former nomenclature ‘contrast-induced nephropathy’ (CIN).7 The main changes are that in CIN, the diagnostic threshold for creatinine was 0.5 mg/dl while it is 0.3 mg/dl in PC-AKI, and the definition no longer includes causation.

While it is difficult to quantify the incidence of PC-AKI, we know that the vast majority of cases are reversible increases of creatinine and only a small percentage are irreversible. In our study, only 3.8% of patients with a glomerular filtration rate of under 45 ml/min had irreversible PC-AKI.8 In all cases, PC-AKI appeared in patients over 70 years of age with moderate or severe chronic kidney disease (CKD); multiple cardiovascular, oncological, or post-renal transplant risk factors; or a history of abdominal—especially urological—cancer surgery.8,9

Risk factors for developing PC-AKI are divided into two types: those associated with the contrast, and those associated with the patient.5,6

- -

Risk factors associated with the iodinated contrast include the dose, the repetition of contrast tests within a short period of time, and the injection of intra-arterial contrast above the renal arteries in such a way that the iodinated contrast reaches the kidney undiluted; this form of injection is called intra-arterial injection with first-pass renal exposure.6 When intra-arterial contrast reaches the renal arteries diluted, it is called intra-arterial injection with second-pass renal exposure.

- -

Risk factors associated with the patient include dehydration, previous acute or chronic kidney function deficiency, and the patient being unstable or critically ill.5

Currently, risk factors associated with renal failure are not generally considered to be specific risk factors for PC-AKI (diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, high blood pressure, nephrotoxic medication, cancer, single kidney, advanced age, multiple myeloma, etc.).5,6

Prophylaxis against post-contrast acute kidney injury (PC-AKI)Intravenous hydration is currently considered the only effective prophylactic measure for the prophylaxis of PC-AKI. Since the 2018 publication of the AMACING trial, the CKD threshold for prophylaxis has been lowered from a GFR of 45 ml/min/1.73 m2 (KDIGO CKD G3b) to less than 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 (KDIGO CKD G4). This was due to the trial's findings that no hydration was non-inferior to hydration as a form of CKD prophylaxis in patients with a GFR of greater than 30 ml/min.10 Not all radiology and clinical societies agree with this new prophylactic threshold and consider it a risk to leave all CKD patients, other than those in KDIGO groups 4 and 5, without prophylactic hydration, preferring to continue with the higher thresholds of 45 ml/min or even 60 ml/min in the case of the European Society of Oncology.11

Oral hydration is not inferior to intravenous hydration as a form of PC-AKI prophylaxis in patients with a GFR of 45−30 ml/min/1.73 m2, as demonstrated in the NICIR trial.8 A study is currently underway to demonstrate the same for patients with a GFR between 30–15 ml/min/1.73 m2.12 As will be seen in the section ‘Oral hydration prior to a radiological test’, fasting of clear fluids, especially water, is no longer required prior to radiological examinations, so oral hydration can and should be generalised, as some societies are calling for, so that no vulnerable patients are left without prophylactic hydration.

Proposed prophylactic protocol for post-contrast acute kidney injury (PC-AKI)Our proposed prophylaxis protocol, based on guidelines published by the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) and the American College of Radiology (ACR) is described in Fig. 1. It has already been introduced in some radiological societies and is now the official protocol for Radiòlegs de Catalunya.5,13,14

Proposed prophylactic protocol for PC-AKI.

Radiòlegs de Catalunya official protocol based on the most recent update of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology guidelines. See the critical review of these guidelines published in this journal in 2020.20

The most prominent features of this protocol are:

- -

In outpatients, the last available laboratory results can be dated six months before the test, rather than three months. This extension is justified by the fact that in practice, no significant variations have been observed between the two timeframes in this patient group. Furthermore, by extending the timeframe, the results from laboratory testing are more likely to be available, the extra time is more convenient for patients, and it simplifies test logistics.

- -

We make oral hydration universal. The paperwork given to patients when they are given their appointment recommends that all patients drink 500 ml water during the two hours prior to the iodinated contrast-enhanced test and 2000 ml water over the 24 h that follow the test, unless otherwise indicated by their doctor.

- -

Patients whose doctors have instructed them to restrict fluids are usually aware of these limitations. These are mainly patients with ascites, liver failure, severe congestive heart failure or those on dialysis. In these cases, the advice is to avoid oral hydration in line with their medical restrictions. By following their doctor’s instructions, we can safely filter patients for whom our universal advice is contraindicated and guarantee an appropriate therapeutical management.

- -

The intravenous hydration regimen for patients with a GFR of between 30 and 15 ml/min/1.73 m2 lasts one hour (short regimen) and is carried out by the nursing unit of the diagnostic radiology service. Prior to the test, 3 ml/kg/h of saline or sodium bicarbonate is administered. Some studies are currently underway5,6 to determine if these patients will also be able to receive oral hydration in the future and be equally protected.

- -

In patients with a GFR of less than 15 ml/min/1.73 m2, long intravenous hydration is carried out (long regimen, 1 h/4 h) which begins one hour before the procedure and lasts until four hours after. The first part is the same as in the short hydration regimen (1 h). This is then complemented by 1 ml/kg/h of either saline or sodium bicarbonate over the four hours following the radiological test (4 h). This will preferably be carried out in the outpatient sections of the service that has requested the test. In these cases, it is very important that the doctor who requests the test is the one to explicitly authorise that the patient can be administered intravenous iodinated contrast.5,6

- -

The prophylaxis protocol is the same whether iodinated contrast is injected intraarterially or intravenously. Long hydration (1 h/4 h) will only be carried out for patients who are especially vulnerable or who require CM administration with first-pass renal exposure.

- -

It is important to know if the patient is hospitalised or has come from A&E and is already undergoing saline hydration as these patients are considered to be hydrated already and the test does not need to be delayed for further hydration.

- -

Advanced Practice Nurses (APNs) are responsible for screening and pre-assessment of the patient. They provide the necessary information, monitor laboratory tests and follow up the patients who come under the prophylactic hydration protocol. The practical implementation of this protocol is explained in the corresponding article of this monograph.

- -

If after 48–72 h there is no significant change in the creatinine value, no action should be taken; if the increase in creatinine is equal to or greater than 0.3 mg/dl, a check-up should be done after 15 days; and if this deterioration persists, the patient should be sent for a kidney assessment.

The following are answers to the most frequently asked questions about our proposed prophylactic protocol for PC-AKI in clinical practice:

- -

The imaging study can be performed with both low-osmolar and iso-osmolar iodinated contrast. Iso-osmolar contrast has not been shown to be less nephrotoxic than low-osmolar contrast.

- -

Either saline solution or sodium bicarbonate can be used indistinctly.

- -

A practical and simple way of determining which patients cannot be assigned oral hydration is to ask the patient if their doctor has restricted their fluid intake (heart failure, ascites, dialysis, liver failure). This question should feature on the documents given to patients when they are given an appointment, especially when this documentation recommends universal oral hydration.

- -

Cardiologists use longer hydration regimens with lower doses of hydration/hour to avoid cardiac overload in patients with heart failure.

- -

There are no nephroprotective medications (n-acetylcysteine must NOT be administered).

- -

Before carrying out an iodinated contrast study, NO medication should be interrupted. Metformin should not be interrupted before carrying out an iodinated contrast test. Metformin is contraindicated in patients with a GFR of less than 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 as iodinated contrast can cause lactic acidosis in these kinds of patients if dehydrated. Upon encountering a patient of these characteristics, discontinue metformin 48 h after the test and refer the patient to the endocrinology service. The test should always go ahead.

- -

Upon encountering a patient aged over 70 years with no GFR, ask the following questions: 1) Are you a cancer patient? 2) Do you have kidney disease? 3) Have you had kidney, intestinal or bladder surgery? If the answer to any of these questions is yes, the short prophylactic hydration regimen (1 h) should be performed. If the patient is younger than 70 years old, the test can be performed without hesitation.

- -

Iodinated contrast studies can be performed if the patient is on dialysis and no coordination with dialysis is required. Only those patients on dialysis with a residual urine output greater than 500 ml/day should follow the long prophylaxis (1 h/4 h) in order to preserve residual urine output. The physician requesting the imaging study should be the one to advise us of this situation.

- -

If the patient only has one kidney, but their renal function is normal, no prophylactic measures are required.

- -

The ESUR’s Contrast Safety Media Committee (CSMC) has recently published an article in European Radiology on the recommended period between two contrast-enhanced studies.15 It concludes that laboratory tests should always be carried out before contrast-enhanced studies. The ESUR's CSMC has also recently published information on interferences between contrasts and the different laboratory parameters referenced in the bibliography.16

- -

Intravenous iodinated contrast can be administered to patients with suspected pheochromocytoma. Intraarterial iodinated contrast is not recommended for patients with suspected pheochromocytoma.

- -

Iodinated contrast can be administered to patients with thyroid disorders. Iodinated contrast should not be administered to patients undergoing treatment with the isotope I131.

- -

Iodinated contrast can be administered to pregnant patients. X-rays should be avoided during the first trimester. From the second trimester onwards, the need for a test with iodinated contrast or x-rays should be assessed on an individual basis, determining whether an alternative test can be performed with the same level of diagnostic efficacy, and no radiation or contrast. Breastfeeding should not be interrupted if iodinated contrast is administered.

- -

Always use the lowest possible dose of contrast adjusted to weight.

Over time, the need and guidelines for fasting before contrast-enhanced imaging studies have evolved to improve the quality of scans, reduce risks and provide greater patient comfort. Pre-procedural fasting instructions arose from an alleged need to improve imaging studies, reduce food interference with image interpretation, and protect patients from vomiting and aspiration pneumonia. Fasting prior to intravenous contrast administration dates back to the days when high-osmolar ionic iodinated contrast agents were used and many patients vomited.

With the new, much safer contrast media, it is necessary to update these recommendations to reflect the new findings on their use and safety.4

Fasting is not currently recommended prior to the administration of low- or iso-osmolar non-ionic iodinated contrast agents or gadolinium-based contrast agents as the incidence of vomiting is almost non-existent.5,6,14 The new recommendations have placed greater emphasis on the importance of adequate hydration prior to contrast-enhanced imaging studies. Dehydration can cause general discomfort, weakness and fatigue or lead to dizziness, light-headedness, disorientation or confusion in patients. This can make patients feel uncomfortable and uncooperative during imaging studies. It is recommended that patients are well hydrated and that fluids are not restricted prior to contrast-enhanced studies to protect renal function and improve contrast tolerance.9

The presence of food in the stomach does not generally affect CT and MR image interpretation.17 Fasting of solids is only recommended for upper abdominal studies (gallbladder, pancreas) or for studies of the gastrointestinal tract (CT enterography, MR enterography, CT colonography, MR colonography). It is also recommended in remote or fluoroscopic studies. The aim of fasting solids in these cases is to ensure that the bowel is clean so that more accurate images can be obtained, rather than any safety reasons.18

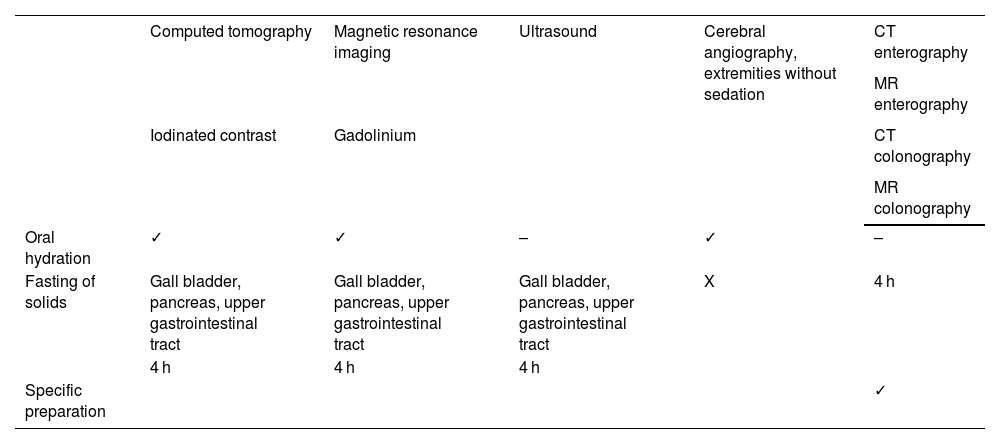

The recommended fasting time for solids in contrast-enhanced imaging studies may vary depending on the type of study to be performed and the specific policies of the radiology centre: it can range from two to four hours. In addition to fasting solids, it is also important to allow the patient to drink water right up to the study in order to stay hydrated.19 Fasting guidelines for the different tests are summarised in Table 1.

Protocol for pre-imaging study fasting (CT, MRI, angiography).

| Computed tomography | Magnetic resonance imaging | Ultrasound | Cerebral angiography, extremities without sedation | CT enterography | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR enterography | |||||

| Iodinated contrast | Gadolinium | CT colonography | |||

| MR colonography | |||||

| Oral hydration | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – |

| Fasting of solids | Gall bladder, pancreas, upper gastrointestinal tract | Gall bladder, pancreas, upper gastrointestinal tract | Gall bladder, pancreas, upper gastrointestinal tract | X | 4 h |

| 4 h | 4 h | 4 h | |||

| Specific preparation | ✓ |

All the authors have been involved in developing the PC-AKI protocol presented in this review, in drafting the article, critically reviewing the intellectual content, and approving the final version of the submitted manuscript.

FundingThis research has not received funding support from public sector agencies, the business sector or any non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.