Understanding of Alzheimer disease (AD) is fundamental for early diagnosis and to reduce caregiver burden. The objective of this study is to evaluate the degree of understanding of AD among informal caregivers and different segments of the general population through the Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS).

Patients and methodsWe assessed the knowledge of caregivers in different follow-up periods (less than one year, between 1 and 5 years, and over 5 years since diagnosis) and individuals from the general population. ADKS scores were grouped into different items: life impact, risk factors, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, disease progression, and caregiving.

ResultsA total of 419 people (215 caregivers and 204 individuals from the general population) were included in the study. No significant differences were found between groups for overall ADKS score (19.1 vs 18.8, P = .9). There is a scarce knowledge of disease risk factors (49.3%) or the care needed (51.2%), while symptoms (78.6%) and course of the disease (77.2%) were the best understood aspects. Older caregiver age was correlated with worse ADKS scores overall and for life impact, symptoms, treatment, and disease progression (P < .05). Time since diagnosis improved caregivers’ knowledge of AD symptoms (P = .00) and diagnosis (P = .05).

ConclusionAssessing the degree of understanding of AD is essential to the development of health education strategies both in the general population and among caregivers.

El conocimiento de la enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA) es fundamental para el diagnóstico precoz y para reducir la sobrecarga del cuidador. El objetivo fue evaluar el grado de conocimiento de la EA mediante la Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS) en cuidadores informales y diferentes segmentos de población.

Sujetos y métodosSe evaluó el conocimiento a cuidadores en diferente periodo de seguimiento (menor de 1 año, entre 1-5 y más de 5 años desde el diagnóstico) y sujetos de la población general (PG). La puntuación ADKS se agrupó en distintos ítems: impacto vital, factores de riesgo, síntomas, diagnóstico, tratamiento, progresión de la enfermedad y cuidadores.

ResultadosTotal de 419 personas; 215 cuidadores, 204 PG. Respecto a la puntuación global de la escala no se encontraron diferencias entre ambos grupos (19.1 vs 18.8; p = 0.9). Destaca un escaso conocimiento de los factores de riesgo de la enfermedad (49.3%) y de los cuidados necesarios (51.2%) mientras que los síntomas (78.6%) y el curso de la enfermedad (77.2%) fueron los aspectos mejor reconocidos. Entre las variables, la edad del cuidador se correlacionó con peor puntuación total de la escala ADKS, peor conocimiento sobre el impacto vital, síntomas, cuidados y de la progresión de la enfermedad (p < 0.05). La duración de los cuidadores mejoró el conocimiento de los síntomas (p = 0.00) y el diagnóstico de la enfermedad (p = 0.05).

ConclusiónEvaluar el grado de conocimiento de la enfermedad es fundamental para poder elaborar estrategias de educación sanitaria tanto a nivel poblacional como en los cuidadores.

Alzheimer disease (AD) is the main cause of cognitive impairment in Western countries, representing the second leading reason for neurological consultation; it is a healthcare and economic issue of great importance.1–3

The behavioural alterations that develop during the course of the disease represent the main cause of caregiver burden and patient institutionalisation. In parallel, the use of psychoactive drugs to control these alterations has been shown to increase the risk of death in these patients.4

Assessing the level of understanding of AD among caregivers and in the general population is essential to optimise healthcare and, ultimately, to improve patient and caregiver quality of life and to decrease their burden. According to numerous studies, individuals with better understanding of the disease are more likely to identify it early and search for an optimal treatment.5–8 Furthermore, education and training with healthcare professionals may improve patient outcomes in clinical and community settings,9 and greater understanding of the disease in the general population may reduce stigma and increase social support.10

However, assessing the understanding of the concept of dementia and/or AD and its implications will be useful for the general population and for caregivers, enabling us to identify the differences in understanding among people responsible for care and treatment of the disease,11 to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and to assess whether public information campaigns have met the objectives established.

Various scales assess the understanding of AD among caregivers and the general population.12 The most noteworthy scales include the Dementia Knowledge Assessment Scale11 and the Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS), which have been shown to be useful in several populations, including among healthcare professionals, caregivers, students, and the general population.13 However, no results have been published regarding the use of any of these scales in the Spanish population.

The aim of this study was to assess the level of knowledge of AD. To this end, we compared the results of informal caregivers of patients with different AD progression times and results from the general population. We also assessed the association between understanding of the different aspects of AD, and demographic characteristics, education level, family history, and progression time.

Patients and methodsThis is a cross-sectional descriptive study including individuals who were anonymously administered the ADKS,13 which was created to assess the understanding of AD in the general population, patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals. This is an adapted version of another widely used scale, the Alzheimer’s Disease Knowledge Test.14 The ADKS includes 30 “true or false” questions reflecting the current scientific understanding of AD. Questions assess understanding of a variety of aspects of the disease, including its aetiology, risk factors, assessment and diagnosis, symptoms, progression, treatment, and care. Each correct answer is scored with one point, with a maximum total score of 30 points. The English-language version was adapted to Spanish with the translation/back-translation method.

The survey was conducted in the Cognitive Impairment Unit’s waiting room prior to consultation, in the case of caregivers, and at 2 primary care centres, in the case of the general population. We included all informal caregivers of patients diagnosed with probable or possible AD according to the NIA-AA criteria.15

We excluded professional caregivers, companions of institutionalised patients who had not been their primary caregiver, and the caregivers of patients with other types of dementia.

We recorded the following variables for all participants: age, sex, level of schooling, family history of cognitive impairment, and previous knowledge of the disease. For caregivers, we also assessed living arrangements, disease progression time, and whether they were caring for a newly diagnosed patient or a patient under follow-up.

For clinical and demographic comparisons between caregivers and the general population, we used the chi-square test and the Fisher exact test. We used the t test and ANOVA to compare means. Correlation studies were conducted using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

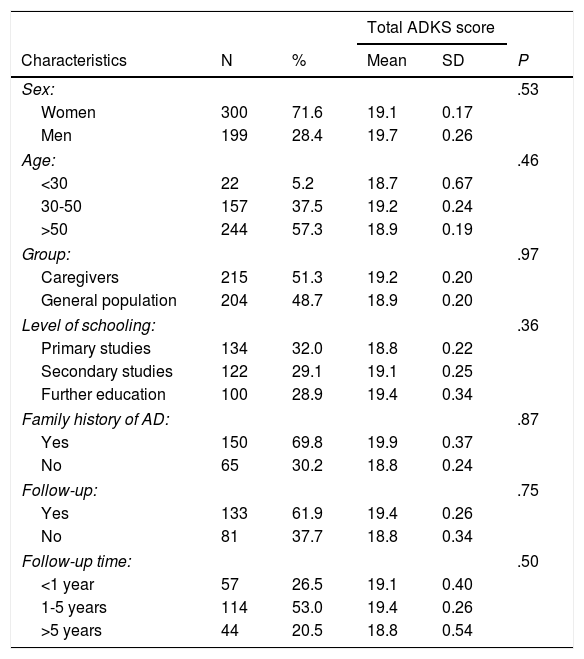

ResultsWe distributed the survey to 419 individuals: 215 (51.3%) informal caregivers and 204 (48.7%) members of the general population. Women accounted for 71.3% of the sample (n = 300). Mean age (standard deviation) was 51.9 (0.6) years. Of the total sample, 59.0% lived in an urban setting (Table 1).

Population characteristics and their association with the understanding of Alzheimer disease.

| Total ADKS score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | N | % | Mean | SD | P |

| Sex: | .53 | ||||

| Women | 300 | 71.6 | 19.1 | 0.17 | |

| Men | 199 | 28.4 | 19.7 | 0.26 | |

| Age: | .46 | ||||

| <30 | 22 | 5.2 | 18.7 | 0.67 | |

| 30-50 | 157 | 37.5 | 19.2 | 0.24 | |

| >50 | 244 | 57.3 | 18.9 | 0.19 | |

| Group: | .97 | ||||

| Caregivers | 215 | 51.3 | 19.2 | 0.20 | |

| General population | 204 | 48.7 | 18.9 | 0.20 | |

| Level of schooling: | .36 | ||||

| Primary studies | 134 | 32.0 | 18.8 | 0.22 | |

| Secondary studies | 122 | 29.1 | 19.1 | 0.25 | |

| Further education | 100 | 28.9 | 19.4 | 0.34 | |

| Family history of AD: | .87 | ||||

| Yes | 150 | 69.8 | 19.9 | 0.37 | |

| No | 65 | 30.2 | 18.8 | 0.24 | |

| Follow-up: | .75 | ||||

| Yes | 133 | 61.9 | 19.4 | 0.26 | |

| No | 81 | 37.7 | 18.8 | 0.34 | |

| Follow-up time: | .50 | ||||

| <1 year | 57 | 26.5 | 19.1 | 0.40 | |

| 1-5 years | 114 | 53.0 | 19.4 | 0.26 | |

| >5 years | 44 | 20.5 | 18.8 | 0.54 | |

Mean total ADKS score was 19.0 (0.15) points. By subgroup, we found mean scores of 19.2 (0.20) among caregivers and 18.9 (0.20) among the general population (P = .97). Among caregivers, we observed no differences between those who had cared for the patient for less than one year (19.1 [0.40]), 1-5 years (19.4 [0.26]), or more than 5 years (18.8 [0.54]) (P = .5).

Higher percentages of correct responses were recorded for items related with disease progression; 91.9% of caregivers knew that patients will need 24-h supervision as the disease progresses, and 91.1% knew that no curative treatment exists. Other issues well understood by most of the population were the increase in fall risk as the disease progresses (88.1%) and the fact that AD is a type of dementia (87.6%).

On the other hand, the questions with a higher percentage of incorrect answers included those related to AD risk factors, such as whether hypercholesterolaemia (15% of correct answers) or arterial hypertension (21.5%) increase the risk of AD. We also observed limited knowledge of issues related to patient management, such as the possible usefulness of reminder notes in this type of patients (21.5% of correct answers) or whether patients need immediate care when they begin to present problems with self-care (22.4%).

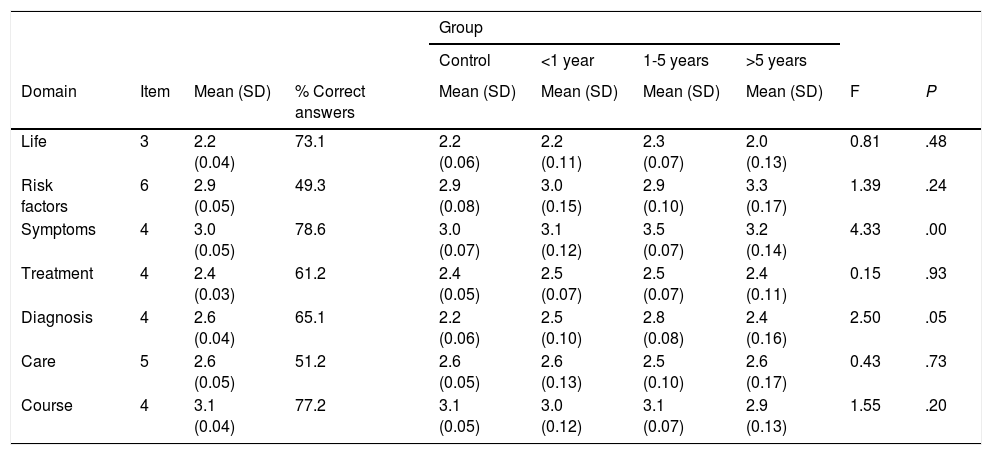

ADKS questions may be classified into 7 groups according to their content: life impact, risk factors, symptoms, treatment, diagnosis, caregiving, and course. Table 2 shows the percentage of correct answers in each area. Less well-understood variables for the general population included AD risk factors (49.3% of correct answers) and the healthcare needed (51.2%). On the other hand, symptoms (78.6%) and course (77.2%) were the aspects best understood by the general population (Table 2).

ADKS subscale scores for each study group.

| Group | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | <1 year | 1-5 years | >5 years | ||||||

| Domain | Item | Mean (SD) | % Correct answers | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | F | P |

| Life | 3 | 2.2 (0.04) | 73.1 | 2.2 (0.06) | 2.2 (0.11) | 2.3 (0.07) | 2.0 (0.13) | 0.81 | .48 |

| Risk factors | 6 | 2.9 (0.05) | 49.3 | 2.9 (0.08) | 3.0 (0.15) | 2.9 (0.10) | 3.3 (0.17) | 1.39 | .24 |

| Symptoms | 4 | 3.0 (0.05) | 78.6 | 3.0 (0.07) | 3.1 (0.12) | 3.5 (0.07) | 3.2 (0.14) | 4.33 | .00 |

| Treatment | 4 | 2.4 (0.03) | 61.2 | 2.4 (0.05) | 2.5 (0.07) | 2.5 (0.07) | 2.4 (0.11) | 0.15 | .93 |

| Diagnosis | 4 | 2.6 (0.04) | 65.1 | 2.2 (0.06) | 2.5 (0.10) | 2.8 (0.08) | 2.4 (0.16) | 2.50 | .05 |

| Care | 5 | 2.6 (0.05) | 51.2 | 2.6 (0.05) | 2.6 (0.13) | 2.5 (0.10) | 2.6 (0.17) | 0.43 | .73 |

| Course | 4 | 3.1 (0.04) | 77.2 | 3.1 (0.05) | 3.0 (0.12) | 3.1 (0.07) | 2.9 (0.13) | 1.55 | .20 |

In the comparison between the subgroups of the study population, caregivers who had cared for patients for between 1 and 5 years scored higher for understanding of symptoms (P = .00) and for diagnosis of the disease (P = .05). After the Bonferroni correction was applied, the difference persisted for understanding of symptoms (P = .003) but not for diagnosis of the disease (P = .27) (Table 2).

ADKS total and item scores showed no significant differences associated with family history of AD (19.9 [0.37] for participants with family history of AD vs 18.8 [0.24] for those without; P = .87), sex (18.7 [0.26] in men vs 19.1 [0.18] in women; P = .35), or the patient’s geographical surroundings (18.9 [0.24] rural vs 19.1 [0.19] urban; P = .52).

Respondents’ age was negatively correlated with understanding of risk factors (r = –0.098; P = .045) and of the care needed by the patient (r = –0.134; P = .006). When analysing by subgroup, we observed that especially among caregivers, age was correlated with poorer total ADKS score (r = –0.194; P = .004) and poorer understanding of life impact (r = –0.156; P = .02), symptoms (r = –0.134; P = .04), the care needed by the patient (r = –0.156; P = .02), and disease progression (r = –0.164; P = .01). On the other hand, ADKS scores in the general population did not show a correlation with age (r = 0.030; P = .671); only the understanding of risk factors was poorer in older individuals (r = –0.177; P = .01).

Level of schooling was not associated with differences in understanding of the disease, either in the general population or among caregivers (P > .05). Only in the case of understanding of the disease, individuals with a higher level of education obtained higher scores for understanding of healthcare needs than those who had no schooling or primary studies (2.97 [0.14] vs 2.30 [0.12]; P = .001); statistical significance persisted after application of the Bonferroni correction.

DiscussionThis study analyses for the first time the understanding of AD in the Spanish population, in a sample of informal caregivers of patients with AD and in the general population. In this sample, we observed good general understanding of AD. The increasing prevalence of the disease due to population ageing may be generating greater interest in the disease, which would explain this understanding. However, we observed differences in the information available for different sections of the populations, as well as significant gaps in the understanding of some areas.

If we compare the total scores of our population with those reported in other studies, we observe that scores were generally lower in our study. Thus, whereas mean scores in the general population and among caregivers were 18.9 (0.20) and 19.2 (0.20) respectively, the study by Carpenter et al.13 reported total scores of 22.7 (0.42) in American caregivers and 24.1 (0.29) in the general population. In other studies including healthcare professionals, total scores were 24.1 (0.25) among Norwegian psychologists16 or 23.6 (0.33) among Australian healthcare professionals.17 Therefore, although our data can only be compared with the original study by Carpenter et al.,13 our scores seem to be slightly lower than those obtained in other countries of a similar socioeconomic level but with more years of schooling, especially among older individuals.

If we analyse specific aspects of the disease, we observe that knowledge of certain modifiable risk factors for dementia is generally poor in most studies.18–23 In our population, only 21.5% and 15.5% of respondents were aware that arterial hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia, respectively, are risk factors for AD. These figures are similar to those reported by Hudson et al.20; in that study, only 25% of respondents knew that hypertension and high cholesterol levels increased the risk of developing dementia. Another study reported that only 39% of respondents identified smoking as a risk factor.24 While many people may be interested in knowing what diet, supplements, and other lifestyle interventions may help prevent the disease, these topics are frequently addressed in the mass media using inconclusive or inconsistent data, thereby decreasing certainty among the population.25

One of the most common misconceptions reported in many studies is the idea that dementia is a normal process in ageing and that it is not clear at what point age-related memory problems become severe enough to suggest dementia. This finding is not surprising, since many healthcare professionals, even physicians trained to diagnose and treat such diseases as dementia, frequently present similar concerns.26–28 However, 87.6% of respondents in our sample were aware of the association between AD and dementia and considered it a disease rather than a natural phenomenon associated with ageing.

According to the literature, understanding of the basic symptoms and typical course of the disease generally seems to be more robust. In contrast, details of the impact of the disease and how caregivers could better help patients with dementia are less well known, even among caregivers.29

The characteristics related to better understanding of the disease remain a controversial issue. For instance, in some studies, women have shown greater knowledge,22,30–36 whereas we observed no sex-related differences in our study.

Particularly in the caregiver subgroup, older age was associated with poorer knowledge of the disease, both in general and in specific aspects such as life impact, symptoms, care needed by the patient, and disease progression with age. Some studies report similar findings,8,30,37 whereas others have found that younger individuals have poorer knowledge of the disease in general and of risk factors in particular.18

In terms of the level of schooling, we found that individuals with higher levels of education scored better on understanding of the care needed than those with primary or no studies. This observation is consistent with those published in the literature, regardless of the scale used: other studies report better understanding both of dementia in general and of such specific domains as pharmacological treatment and risk and prevention factors.30,32,38

One strength of our study was the use of an already established scale with demonstrated reliability.13 A recent systematic review assessing 40 studies on the understanding of the disease in several countries, not including Spain,12 reported that up to 77% of studies developed original surveys; only 9 studies used the ADKS scale, 2 used the Dementia Knowledge Questionnaire, and another 2 the Epidemiology/Etiology Diseases Scale.

Although our sample is large and includes different populations in terms of age, education, and living area, one limitation of our study was that all participants were white. Some studies report a lower level of knowledge of the disease in certain ethnic minority communities. Although this seems to be related to lower levels of schooling and not to cultural or religious factors,39,40 no conclusions could be drawn on this subject in our study. Furthermore, experience with the ADKS scale has shown that its internal consistency is relatively low, which may limit the results obtained. This brief scale excludes certain specific topics such as the typical rate of decline, the daily variability of symptoms, genetic risk, or the use of supplements. It is therefore important to acknowledge that while the ADKS is not a comprehensive assessment scale, it does offer a general view of an individual’s knowledge of AD. For this reason, this scale may also present a ceiling effect in more expert groups. Annear et al.41 recently validated the Dementia Knowledge Assessment Scale11 in different study populations and have demonstrated that it correlates well with the ADKS; therefore, both instruments seem to evaluate similar aspects of the disease. However, the Dementia Knowledge Assessment Scale has been shown to be more useful in detecting changes in the degree of knowledge, especially after training periods, and should be considered in further studies.42

We conclude that such assessment tools as the ADKS may play a role in assessing where training is needed. In fact, merely administering the test may help raise awareness among the population about aspects of dementia that they were previously unaware of. Many participants in our study acknowledged that completing the questionnaire helped them to identify gaps in their knowledge and misconceptions about the disease. Therefore, completing the ADKS or similar questionnaires would represent an intervention in itself. At the population level, national health education programmes and awareness campaigns should be based on the public’s knowledge rather than on what political experts and educators think people know about the disease. In this regard, scales for measuring understanding of dementia are important tools that help in assessing and improving health training and education in order to provide better care and treatment to patients with dementia.

FundingThis study was partially funded by Fundació La Marató TV3 (464/C/2014).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Jorge C, Cetó M, Arias A, Gil MP, López R, Dakterzada F, etal. Nivel de conocimiento de la enfermedad de Alzheimer en cuidadores y población general. Neurología. 2021;36:426–432.