Multiple myeloma (MM) is a disease with multi-organ involvement, heterogeneous and is considered to still be incurable.1,2 Its incidence in Spain is between 2.5 and 3.5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, and accounts for 1.8% of all cancer deaths.3 The correct choice of treatment can result in maintenance of the response, as well as a better quality of life and overall patient survival.4 This requires an adequate analysis of each patient’s situation and individualisation of the treatment, in which the involvement and experience of the haematologist is of utmost importance. There are currently many reference documents on the treatment of patients with MM.5–9 However, recommendations or evidence guides in patients presenting risk factors or poor prognosis are limited.1,10

The objective of this article is to present the reality of the treatment received by high-risk MM patients, according to real clinical practice in Spain. The results have been extracted from an anonymous questionnaire designed to know the usual clinical practice and the real preferences of haematologists from different Spanish facilities that treat MM, whether newly diagnosed or in the field of relapse or progression.

Material and methodsA questionnaire was developed based on a review of the literature focused on the treatment of patients with MM in national and international areas. Patients were evaluated from diagnosis to relapse and refractory cases.

From the results obtained in this review, we identified, on the one hand, the factors that would define the profile of a high-risk patient and, on the other, the treatment variants that should be considered for this type of patient.

With the information collected and the collaboration of a scientific committee formed by members of the Spanish Myeloma Group/Spanish Haematology Treatment Programme (GEM/PETHEMA acronym in Spanish), a structured questionnaire was developed. This was completed on-line, with the objective of obtaining information about the usual clinical practice as well as believed optimal treatment methods of high-risk MM patients in Spain.

The questionnaire included specific questions about the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with high-risk MM and opinions on how it should be, based on the available scientific evidence. Through the GEM/PETHEMA, a total of 221 national haematologists were invited to participate in the study. All the participants had a minimum of 5 years’ experience in MM disease and were dedicated to the treatment and follow-up of these patients in their corresponding sites.

Participating researchers individually signed a commitment to participate and received personal access to complete the study questionnaire on-line. The collected data were analysed in a descriptive, aggregated and dissociated way to preserve the anonymity of the participating specialists. Participation was voluntary and not linked to any fee.

ResultsFifty haematologists (22.6%), with an average experience of 16.2 years in the treatment of MM patients, agreed to participate in the questionnaire and met the selection criteria. The questionnaire was received completed between May and August 2017. Of the total participants, 46 (92%) worked in haematology departments, while the rest worked in onco-haematology departments.

Healthcare reality of multiple myeloma in SpainAccording to 92% of the participants, the reference work which was consulted for the treatment of MM patients who were not candidates for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) corresponds to the consensus document of the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG).6 It is followed in usual clinical practice by 88%. It is also common to use the ESMO guides5 (78%), the NCCN guidelines9 (76%), the European Perspective on Multiple Myeloma Treatment paper7 (66%) and the Castilla y León MM oncology guide8 (64%). Additionally, haematologists reported that in their clinical practice they consulted another 20 key references as support in the treatment of these patients. 87% of the participants indicated that they had MM management protocols in their sites (20% were mandatory).

Regarding the management of patients with high-risk MM, 90% stressed that it would be interesting to have a national guide or reference document available, since the current documents are not fitting for the healthcare reality in the management of this specific patient profile. In addition, 53% of haematologists indicated having limitations of access in their work sites to some treatments that they considered relevant for the adequate treatment of high-risk MM patients.

Criteria that define the profile of a high-risk patient100% of the participants highlighted the presence of plasma cell leukaemia among the factors that define the profile of high-risk MM patients. 91% also considered the presence of cytogenetic markers and 80% extramedullary disease or a stage III according to the Revised International Staging System.

In relation to cytogenetic markers, 98% of participants routinely determine them, while the remaining 2% only use the markers if other associated risk factors have been previously identified. The most used system was fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), in 78% of the results. The presence of cytogenetic alterations would condition the choice of treatment according to 69% of haematologists, especially if they identified either 17p deletion or poor prognosis translocations that affect the IGH gene, fundamentally t (4;14) or t (14;16) (53% of opinions).

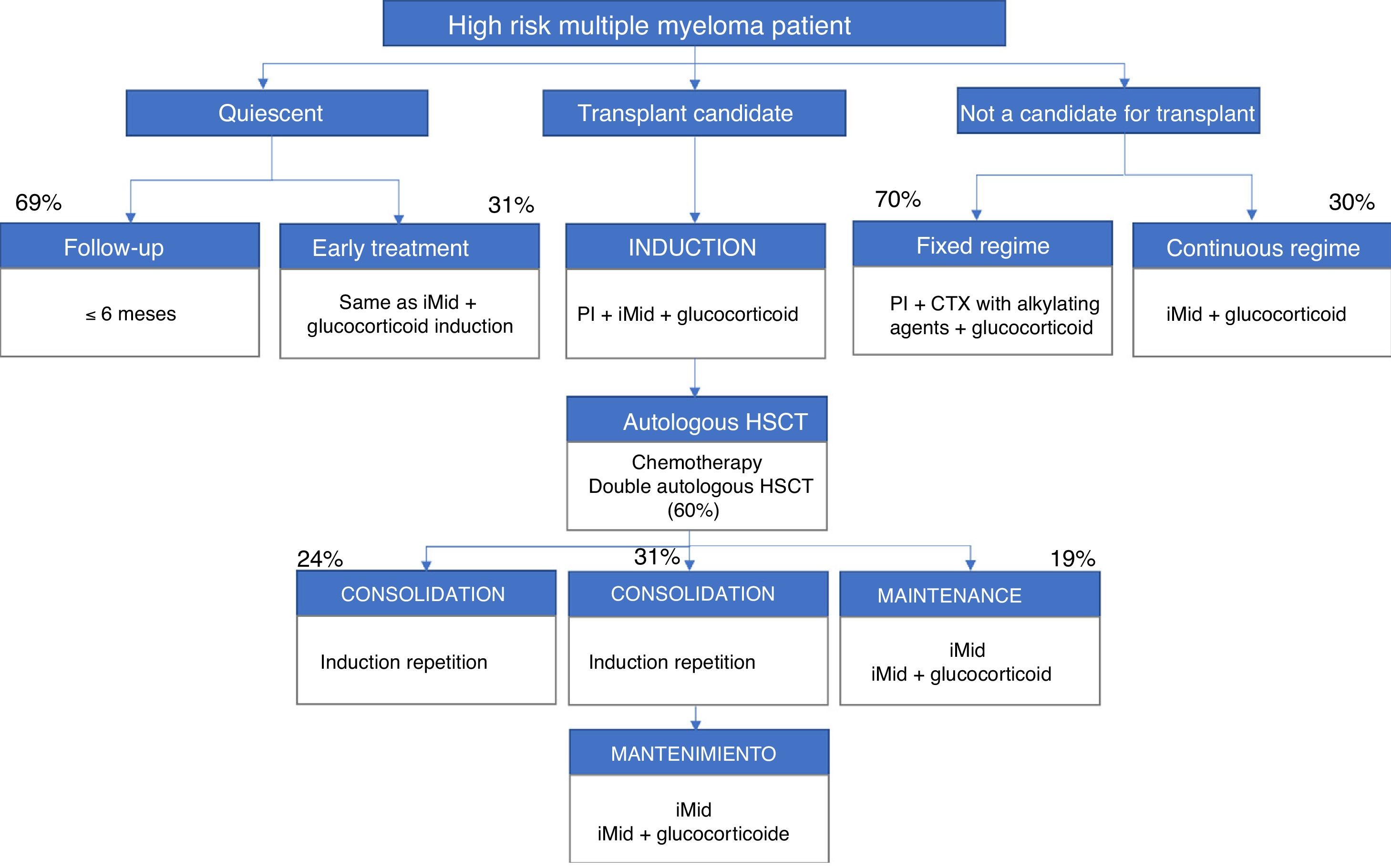

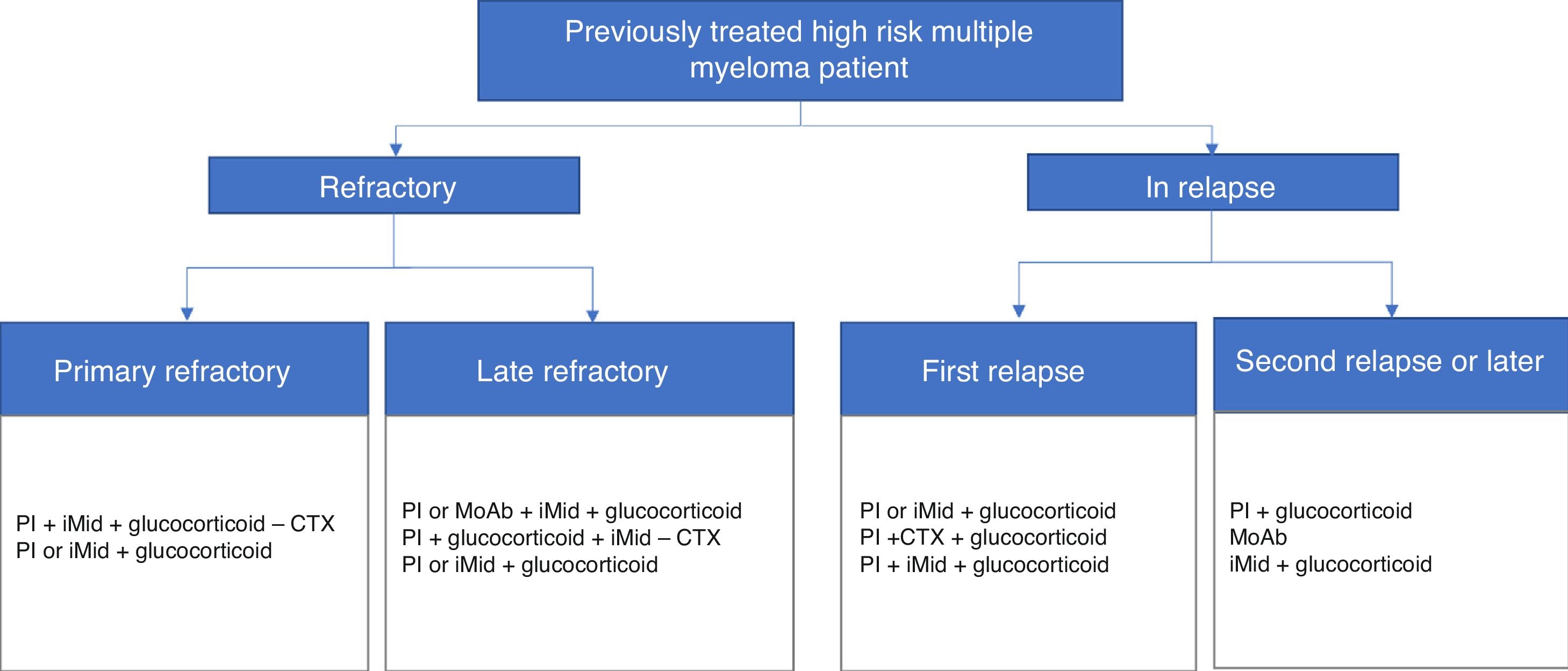

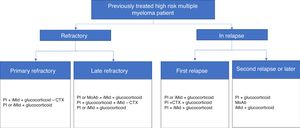

The participants included the patient's own high-risk factors and determinants, i.e. peripheral neuropathy (82%), age (78%), renal failure (78%) and various heart disease (78%). Figs. 1 and 2 present a summary of the treatment algorithms used by the participating haematologists in their own clinical practice for the management of high-risk MM patients.

Diagrams of authorised treatments in Spain for patients with a new diagnosis of high-risk multiple myeloma. They are based on the therapeutic options available between May and August 2017.

iMid: immunomodulatory drugs; PI: proteasome inhibitor; CTX: chemotherapy; HSCT: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Diagrams of authorised treatments in Spain for patients with a diagnosis of treated, refractory or relapsed high-risk multiple myeloma. They are based on the therapeutic options available between May and August 2017.

MoAb: monoclonal antibodies; iMid: immunomodulatory drugs; PI: proteasome inhibitor; CTX chemotherapy.

The recommendations are to continue with periodic follow-up but not to treat the patient with quiescent MM11 (when the early stage MM has no symptoms or complications).5 88% of the participants considered that the decision to treat these patients depends equally on the factors of the individual and those of the tumour. 69% said that they did not start early treatment, although the patient had a profile of high risk of progression, and they limited the case to periodic follow-up. In the case of standard risk patients, follow-up was carried out less frequently (1–3 months or 3–6 months, for 42% and 24% of participants, respectively).

31% of haematologists indicated that they would treat these patients with quiescent MM early on, usually with the same treatment they would have used in symptomatic patients. The combination of an immunomodulatory agent, a proteasome inhibitor and a glucocorticoid would be the treatment of choice for almost half of the participants (47%).

Treatment of high-risk patients who are transplant candidates83% of the participants indicated that in patients who were high risk transplant candidates the patient's own factors and those of the tumour should be considered equally to establish an optimal treatment. The triple combination formed by a proteasome inhibitor, an immunomodulator and a glucocorticoid would be the most commonly used in clinical practice to carry out the induction therapy, according to 74% of haematologists.

At the end of the induction, all participants indicated that they valued the response to treatment. However, only 15% of haematologists indicated that they would choose to repeat the induction in the case of minimal residual positive disease (presence of MM cells that survive a treatment, detected by flow cytometry or molecular sequencing).12

After the induction therapy, 96% of the participants stated that they would perform conditioning with an alkylating agent and an autologous HSCT. In high-risk patients, 60% indicated that they would carry out a double autologous transplant in just over half of their patients (59.8%). Among the main reasons why the double transplant would not be routinely chosen are the logistical limitations of the site itself or the need to refer to other sites.

Post-transplant treatment strategies in this group of patients are very variable. According to the participating haematologists, in clinical practice 31% of the patients were treated with a consolidation strategy followed by long-term maintenance; however, based on their criteria, this option would be the optimum and should be extended to 54% of patients. On the other hand, according to 96% of the participants, in the usual clinical practice there are 26% of the patients who do not receive either consolidation or maintenance and in which periodic follow-up is done only every 1–3 months. Repeating induction therapy is the most widespread consolidation treatment in usual clinical practice for 94% of haematologists.

The treatment of choice in high-risk patients in routine clinical practice is maintenance with an immunomodulator, alone or in combination with a low-dose glucocorticoid, according to 79% of participants. This treatment would be maintained continuously over time (68%) or with a defined long-term schedule (32%) of approximately 22 cycles of duration.

Treatment of high-risk patients who are not transplant candidatesFor 83% of haematologists, the choice of treatment in the high-risk non-transplant patient would depend equally on the tumour’s own factors and those of the individual. In this case, 11% would prioritize the patient's own factors, while 6% would opt for those of the tumour.

70% of haematologists would choose a fixed treatment regimen. This option would be based, in 80% of cases, on a triple combination of a proteasome inhibitor, an alkylating agent and a glucocorticoid, used for an average of 9.4 cycles. In the case of opting for a continuous type regimen, in 75% of the results the option used mainly would be the combination of an immunomodulator and a glucocorticoid.

Treatment of refractory/relapsed patientsTo establish the most appropriate treatment for each refractory or relapsed patient, the main factors to take into account would be the tumour and those of the patient equally, both in the primary refractories (76% of the results) and last line refractory patients (74%), as well as in relapsing patients (87%).

79% of haematologists recognised the need to apply a different treatment to refractory patients and those who relapse. In general, the basis of the treatment for refractory patients would be combinations with a proteasome inhibitor and a monoclonal antibody, or a triple combination of a proteasome inhibitor, an immunomodulator and a glucocorticoid. In the case of relapsed patients, 70% of the participants believe that they should not be stereotyped, but, if so, the reference treatments would correspond to combinations with an immunomodulator if the patient had previously received a proteasome inhibitor, or with a glucocorticoid, in the case of having received an immunomodulator before.

DiscussionThe results presented in this article reflect the real clinical experience and the recommendations of haematologists from different Spanish sites that routinely treat patients with MM according to the resources available between May and August 2017. In general, they show a common trend in the treatment of these patients, which is uniform among the different participating sites and aligned with the general national and international recommendations.1,2,5,6,13 But there is no general consensus or criterion when it comes to managing patients with MM and high risk factors. However, the data collected show that haematologists recognise and consider the factors that define a high-risk profile according to the available guidelines.1,2 In fact, they recognise that the translocations (4;14), (14;16) and (14;20), the deletion (17/17p) and the non-hyperdiploid karyotype constitute high-risk cytogenetic alterations. In addition, the 1q+ are associated with poor prognosis, and the presence of more than 3 cytogenetic alterations confers a very high risk, with reduced survival.14 The high risk MM classification must combine these alterations with the presence of a high classification (in accordance with the International Staging System), an increase in serum LDH, or genetic alterations of risk in the expression profile. Despite this, these factors do not seem to be decisive in the choice of treatment, contrary to that which is recommended internationally,15 and the same conventional treatments applied to a standard risk patient are maintained. When all is said, this fact has been common in the treatment of patients in different countries surrounding us, and it is now that different decisions, based on high risk factors, are being progressively, although gradually, applied.

The results indicate that haematologists in their clinical practice follow the main recommendations for the management of patients with MM5–13 by generally only starting the treatment when there is symptomatology. However, there is evidence that would advocate the early start of treatment in patients with quiescent MM (without symptoms or complications) to improve results.14,16 Many haematologists have declared their preference for this type of approach to the asymptomatic patient. But this is unlikely to occur in the healthcare reality of Spanish hospitals due to the sites' treatment protocols and the limitations of access to certain drugs for the treatment of MM. Currently, studies are being conducted regarding whether the anticipation of the treatment, either to avoid the progression to symptomatic multiple myeloma, or to eradicate the myeloma clone, could improve the results in terms of survival and, perhaps, achieve the cure of some of the patients.14,17

According to the experience of the participating haematologists, patients with symptomatic MM are treated immediately, in general, following the guidelines,5,7,8 but the fact that the patient has high-risk characteristics does not imply intensive treatment on many occasions.10,13 Taking as reference the induction treatment given to high-risk MM patients who are transplant candidates, experts in Spain indicate that the most used combination corresponds to the standard therapy5,7,8 (a proteasome inhibitor, an immunomodulator and a glucocorticoid), while the appropriate treatment in this high-risk patient profile would be to opt for combinations of proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulators, monoclonal antibodies and glucocorticoids and, in young patients, to perform a double autologous HSCT.15 This subgroup of patients constitutes an unmet medical need, so its inclusion in clinical trials is highly recommended.

The same happens when analysing the treatment used in consolidation and maintenance of patients with a high risk and candidates for transplantation, or in patients who are not transplant candidates. The answers included in the questionnaire reflect a clinical practice aligned with the recommended treatment for standard risk patients,5,7,8 but they are not adapted to the needs of high-risk patients.10,13,18

In general, haematologists are aware of the needs of patients with high-risk MM, but, due to: limitations of access to certain treatments; care protocols; and even limited knowledge to recognize these special situations, they cannot generalise the use of specific treatments in this patient profile. These cases would include patients with adverse cytogenetics,19 which require a differential treatment, as well as elderly patients, in which the treatment must be individualised according to their characteristics and physical and functional status, which includes avoiding the systematic and sustained use of glucocorticoids.20

If the treatment of more complex patients is also considered, such as those who are refractory or relapses, the options are multiplied due to the diversity of criteria to consider (previous treatments, the patient's own characteristics) and also the absence of clear guidelines for treatment of this patient profile. However, despite the fact that haematologists recognise the need to perform differential therapeutic management among the different types of refractory patients (primary, late or relapse), the strategies used are very similar. It is precisely in this group of patients that the published literature21–23 offers a greater variety of treatments.

The results reported are intended to reflect the healthcare reality of the treatment of high-risk MM in Spain, but they are merely indicative and descriptive, since participation in this questionnaire has been limited to a sample of 50 haematologists. In addition, the results are based on the experience of these experts and their preferences, but they have not been obtained from a systematic review of medical records. It should also be borne in mind that the results are based on the therapeutic options available between May and August 2017, when the data were collected. However, although more drugs are currently available for the treatment of MM, in some cases, access restrictions and lack of consensus and recommendations by the main cooperative groups make it difficult to treat patients with high-risk MM. Even so, there has recently been an increase in the therapeutic arsenal for the treatment of MM, with numerous trials combining 3, 4 and up to 5 drugs, in an attempt to obtain more complete responses, with undetectable minimal residual disease. Possibly, in some cases, this strategy is the way to continue improving the results of patients with high-risk MM.

ConclusionsThis article offers an overview of the complexity involved in the treatment of patients with high-risk MM in Spain, and it reveals the need to define treatment guidelines which differ from those of standard risk patients, and that allow the treatment to be individualised in order to reduce the impact on the poor prognosis of this type of patients, as far as possible.

FundingThe study has been financed by Takeda Farmacéutica España and the logistic and coordination support of the Real World Insights team of IQVIA España.

Conflict of interestsDr. José-Ángel Hernández-Rivas has received fees for advice and training from Amgen, Janssen, Takeda, Celgene, Abbvie and BMS. Dr. Mercedes Gironella Mesa has received fees for advice and training from Amgen, Janssen, Takeda and Celgene.

The authors appreciate the selfless participation of all the haematologists participating in the study, as well as the collaboration of GEM/PETHEMA.

Please cite this article as: Hernández-Rivas J-Á, Gironella Mesa M. La realidad asistencial del tratamiento del mieloma múltiple de alto riesgo en España. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;154:315–319.