Different measures are recommended to reduce pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). We conducted a study in patients with ERCP treated with rectal diclofenac or lactated Ringer’s solution, or both interventions, to assess whether there is a decrease in the number of cases of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Material and methodsA mixed cohort study involving 1896 patients from 2009 to 2018. Up to June 2012 without treatment (Group I). Subsequently, 100 mg of rectal diclofenac (Group II). Since 2016, lactated Ringer’s solution 200 ml/h during the procedure and 4 h after it, in addition to 500 ml over 30 min when the pancreas was cannulated (Group III). Since 2017, lactated Ringer’s solution plus Diclofenac (Group IV). There were 725 patients in group I, and 530, 227 and 414 patients in groups II, III and IV, respectively. Factors predisposing to post-ERCP pancreatitis and post-ERCP pancreatitis cases that were defined by consensus criteria have been collected.

ResultsThere were 65 cases of post-ERCP pancreatitis (3.4%); 2.9%, 3.4%, 3.1% and 4.3% in groups I, II, III and IV, respectively (p = .640). In group I, there was 4.2% of post-ERCP pancreatitis in naïve papillae and 4%, 4.9% and 6.3% in groups II, III and IV, respectively (p = .585). The severity of post-ERCP pancreatitis and adverse effects were similar in all groups. 38.4% were high-risk patients. There were also no differences in post-ERCP pancreatitis in this group (p = .501).

ConclusionIn this work, no benefit was obtained with diclofenac plus hydration in reducing the number and severity of cases of post-ERCP pancreatitis nor with the other prophylactic measures.

Se aconsejan diferentes medidas para disminuir la pancreatitis post-colangiopancreatografía retrógrada endoscópica (PPCPRE). Efectuamos un estudio en pacientes con CPRE tratados con Diclofenaco rectal o Ringer Lactato o bien ambas intervenciones para valorar si existe una disminución en el número de PPCPRE.

Material y métodosEstudio de cohortes mixto con 1.896 pacientes desde 2009 hasta 2018. Hasta junio de 2012 sin tratamiento (grupo I). Posteriormente 100 mg de diclofenaco rectal (grupo II). Desde 2016 Ringer Lactato 200 ml/h durante el procedimiento y 4 h después del mismo, además 500 ml en 30 min cuando se canuló el páncreas (grupo III). Desde 2017 Ringer Lactato más diclofenaco (grupo IV). Hubo 725 pacientes en el grupo i, 530, 227 y 414 pacientes en grupos II, III y IV. Se han recogido factores predisponentes a PPCPRE y los casos de PPCPRE que fue definida por criterios de consenso.

ResultadosHubo 65 PPCPRE (3,4%); 2,9; 3,4; 3,1 y 4,3% en los grupos I, II, III y IV respectivamente (p = 0,640). En el grupo I hubo un 4,2% de PPCPRE en papilas naïve y un 4; 4,9% y 6,3% en los grupos II, III y IV respectivamente (p = 0,585). La gravedad de PPCPRE y los efectos adversos fueron similares en los grupos. El 38,4% eran pacientes de alto riesgo. Tampoco hubo diferencias de PPCPRE en este grupo (p = 0,501).

ConclusiónEn este trabajo no se ha obtenido beneficio con diclofenaco más hidratación en la disminución del número y gravedad de la PPCPRE. Tampoco con las otras medidas profilácticas.

Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) is one of the most common complications of ERCP.1 In the literature we reviewed, the incidence of this adverse effect varies widely, depending on whether patients are low-risk (1%–10%) or high-risk (25%–30%).2–5

Patient-related factors associated with a higher likelihood of developing PEP and of developing more severe PEP have been documented, such as female sex and age under 60 years, normal serum bilirubin and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.4,5 Other factors are linked to the technique, such as repeated and traumatic cannulation of the papilla, pancreatic sphincterotomy, bile duct dilation with no prior sphincterotomy, biliary sphincterotomy and precut sphincterotomy.6

Protective factors for the development of PEP have also been documented, such as advanced age, malignant stricture and chronic pancreatitis.3

The development of PEP is a multifactorial process that includes mechanical, thermal, chemical, hydrostatic, enzymatic and microbiological damage. Among the different ways studied to reduce the risk of PEP, the insertion of a pancreatic stent has yielded the best outcomes. However, it is not always easy to place a stent and the technique is not without its complications.7

Various pharmacological agents have been used to prevent PEP. Different studies and meta-analyses have shown rectal anti-inflammatory drugs (diclofenac/indomethacin) to reduce its incidence.8,9 Therefore, the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends their use in all patients either before or after ERCP.10

The infusion of lactated Ringer’s solution during ERCP has also proved beneficial in preventing PEP. The mechanisms behind this effect appear to be related to attenuation of the acidity of the pancreatic tissue, preventing the activation of zymogen and maintaining pancreatic microcirculation.11,12 A randomised, double-blind, controlled study was recently published which assessed the use of rectal indomethacin and infusion of lactated Ringer’s solution and found a decrease in the incidence of PEP in this patient group.13

In view of the above, we conducted a study on consecutive patients given rectal diclofenac prior to ERCP, lactated Ringer’s solution during and after ERCP or both interventions (diclofenac plus lactated Ringer’s). The aim was to assess whether any of these prophylactic treatments reduced the number of episodes of PEP.

Material and methodsWe enrolled all consecutive patients who had undergone ERCP since 2009 in our department. This was a study of historical groups, with collection of information retrospectively from 1 January 2009 to 31 May 2012 and prospectively from that date to the end of the study on 31 December 2018. ERCP was performed by only two physician endoscopists with 20 and 6 years of experience in the technique at the beginning of data collection.

From January 2009 to June 2012, patients did not receive any prophylactic treatment; those patients comprise group I. From July 2012 to December 2015, following the indications of the 2010 European PEP prophylaxis guidelines,14 a decision was made to give a rectal diclofenac suppository (100 mg) at the beginning of the examination, unless the patient had an allergy/intolerance to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or suffered from renal failure or active peptic ulcer. These patients make up group II. Following a preliminary assessment of the benefits of diclofenac in reducing PEP which did not find any decrease in this complication, from January 2016 to January 2017, patients were treated with a 200 ml/h IV infusion of lactated Ringer’s during the examination and for four hours afterwards. Patients whose pancreas was cannulated also received 500 ml of lactated Ringer’s in 30 min post-ERCP. (Patients with heart failure were excluded.) These patients form group III. Lastly, patients from 2017 and 2018 were treated with lactated Ringer’s infusion according to the regimen described and were also given 100 mg of rectal diclofenac before the start of ERCP, provided they had no contraindications to the drug. These patients comprise group IV.

Whenever possible, patients with deep or repeated cannulation of the main pancreatic duct were fitted with a 5-French plastic pancreatic stent.

This study was approved by the hospital’s independent ethics committee.

All patients signed an informed consent form.

PEP was defined according to consensus criteria, which include abdominal pain consistent with pancreatitis along with s prolonged hospital stay beyond two days and amylase levels at least three times higher than the upper limit of normal 24 h after the ERCP.15

Also in accordance with consensus criteria,15 PEP severity was classified as minimal (<3 days in hospital), moderate (4–10 days in hospital) or severe (more than 10 days in hospital, development of necrosis or pseudocyst requiring drainage). All patients remained hospitalised for at least 24 h following the ERCP. If the patient developed symptoms suggestive of acute pancreatitis, an amylase test was performed and, in the event of PEP, the appropriate treatment was administered.16 These patients were monitored until hospital discharge.

We collected demographic data from the patients and data related to the technique, sedation received and complications during and after the examination.

An analysis of factors associated with the development of PEP was performed. These factors included both patient-related parameters (age, sex, history of recurrent acute pancreatitis, previous PEP, chronic pancreatitis, bilirubin, choledocholithiasis and malignant stricture) and technique-related parameters (biliary sphincterotomy, pancreatic sphincterotomy, precut, Wirsung duct cannulation, duration of cannulation >10 min, papillary dilation without sphincterotomy, biliary stent, Wirsung duct stent and sedation by an anaesthetist).

Statistical analysisData on each patient and each examination were collected in an Excel workbook and analysed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software package. For the descriptive analysis, mean and standard deviation were used for quantitative variables and frequency distributions were used for qualitative variables. For the bivariate analysis, we used the χ2 test and odds ratios with their corresponding confidence intervals for categorical variables. For the comparison of quantitative variables, we used Student’s t-test where there were two categories and analysis of variance (ANOVA) where there were more than two categories. Lastly, a binary logistic regression model was built using PEP development as the dependent variable and the factors that showed a significant or near-significant (p < 0.1) association according to the bivariate analysis as independent variables.

ResultsA total of 1896 patients were enrolled; 718 of them did not receive any treatment and corresponded to group I. There were 630 patients in group II, 227 in group III and 414 in group IV.

The mean age of the patients was 73.4 (SD 14.1); 1006 were male (53.1%) and 890 were female (46.9%).

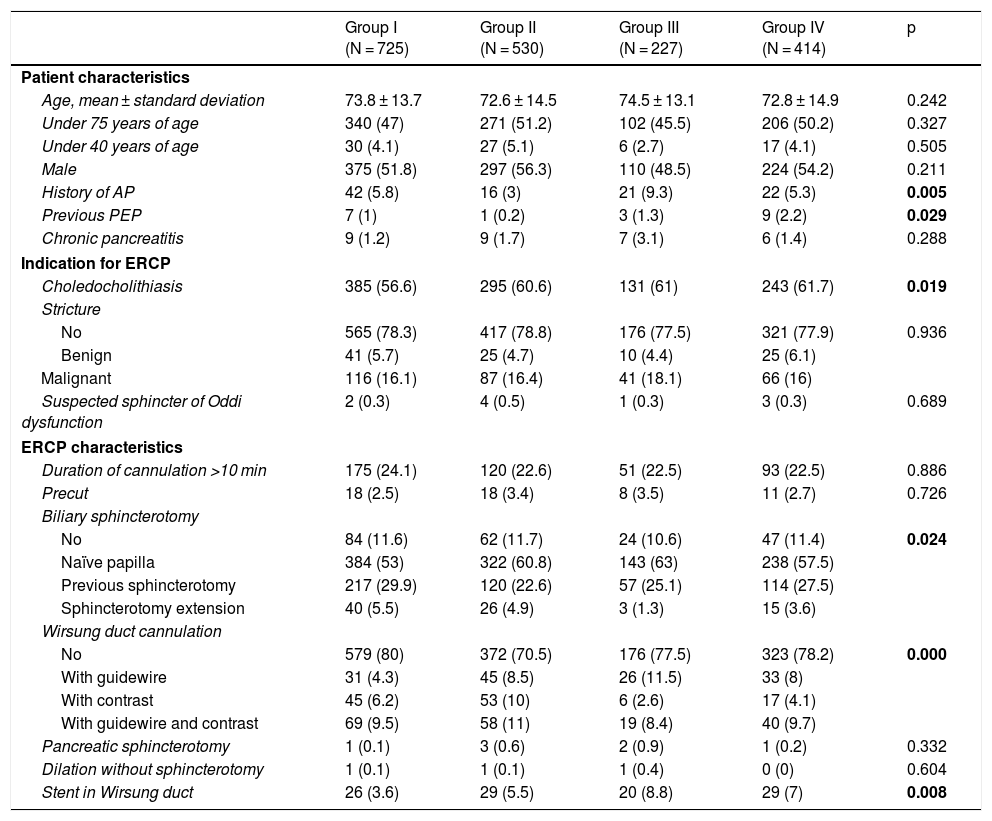

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the different groups of patients. There were significant differences in the characteristics of the patients in group III, in which there were more patients with a prior history of recurrent pancreatitis. There were more cases of previous PEP in group IV and more cases of choledocholithiasis in all treated groups. With regard to the ERCP characteristics, there were significant differences between groups in terms of biliary sphincterotomy on a naïve papilla, which was more common in the treated groups, and Wirsung duct cannulation, which was significantly more common in group II. Plastic stents were placed in the pancreatic duct in 104 patients (6.2%); 26 (3.6%) belonged to group I, 29 (5.5%) belonged to group II, 20 (8.8%) belonged to group III and 29 (7%) belonged to group IV. The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.008).

Baseline characteristics of the different groups of patients.

| Group I (N = 725) | Group II (N = 530) | Group III (N = 227) | Group IV (N = 414) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||||

| Age, mean ± standard deviation | 73.8 ± 13.7 | 72.6 ± 14.5 | 74.5 ± 13.1 | 72.8 ± 14.9 | 0.242 |

| Under 75 years of age | 340 (47) | 271 (51.2) | 102 (45.5) | 206 (50.2) | 0.327 |

| Under 40 years of age | 30 (4.1) | 27 (5.1) | 6 (2.7) | 17 (4.1) | 0.505 |

| Male | 375 (51.8) | 297 (56.3) | 110 (48.5) | 224 (54.2) | 0.211 |

| History of AP | 42 (5.8) | 16 (3) | 21 (9.3) | 22 (5.3) | 0.005 |

| Previous PEP | 7 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (1.3) | 9 (2.2) | 0.029 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 9 (1.2) | 9 (1.7) | 7 (3.1) | 6 (1.4) | 0.288 |

| Indication for ERCP | |||||

| Choledocholithiasis | 385 (56.6) | 295 (60.6) | 131 (61) | 243 (61.7) | 0.019 |

| Stricture | |||||

| No | 565 (78.3) | 417 (78.8) | 176 (77.5) | 321 (77.9) | 0.936 |

| Benign | 41 (5.7) | 25 (4.7) | 10 (4.4) | 25 (6.1) | |

| Malignant | 116 (16.1) | 87 (16.4) | 41 (18.1) | 66 (16) | |

| Suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 0.689 |

| ERCP characteristics | |||||

| Duration of cannulation >10 min | 175 (24.1) | 120 (22.6) | 51 (22.5) | 93 (22.5) | 0.886 |

| Precut | 18 (2.5) | 18 (3.4) | 8 (3.5) | 11 (2.7) | 0.726 |

| Biliary sphincterotomy | |||||

| No | 84 (11.6) | 62 (11.7) | 24 (10.6) | 47 (11.4) | 0.024 |

| Naïve papilla | 384 (53) | 322 (60.8) | 143 (63) | 238 (57.5) | |

| Previous sphincterotomy | 217 (29.9) | 120 (22.6) | 57 (25.1) | 114 (27.5) | |

| Sphincterotomy extension | 40 (5.5) | 26 (4.9) | 3 (1.3) | 15 (3.6) | |

| Wirsung duct cannulation | |||||

| No | 579 (80) | 372 (70.5) | 176 (77.5) | 323 (78.2) | 0.000 |

| With guidewire | 31 (4.3) | 45 (8.5) | 26 (11.5) | 33 (8) | |

| With contrast | 45 (6.2) | 53 (10) | 6 (2.6) | 17 (4.1) | |

| With guidewire and contrast | 69 (9.5) | 58 (11) | 19 (8.4) | 40 (9.7) | |

| Pancreatic sphincterotomy | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 0.332 |

| Dilation without sphincterotomy | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0.604 |

| Stent in Wirsung duct | 26 (3.6) | 29 (5.5) | 20 (8.8) | 29 (7) | 0.008 |

ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: PEP: post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Group I: no treatment; Group II: rectal diclofenac; Group III: hydration with Ringer’s; Group IV: hydration + rectal diclofenac.

Data expressed as n (%).

There were 65 cases of PEP (3.4%): 21 in group I (2.9%), 18 in group II (3.4%), 8 in group III (3.5%) and 18 in group IV (4.3%) (p = 0.640). Of the cases of PEP in patients with a naïve papilla, 4.2% were in group I, 4% were in group II, 4.9% were in group III and 6.3% were in group IV (p = 0.585).

Only 10 patients had suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, two in group I, four in group II, one in group III and three in group IV. There were no cases of PEP in these patients.

PEP was mild in 52 patients (79.3%), with the severity being lower in groups II and IV (11.1% and 23.6%, respectively), and 30% and 37.5% in groups I and III (p = 0.063). Five patients died of PEP within 30 days of the procedure, two in group I, two in group II and one in group IV.

We studied the association of variables and found that neither diclofenac, nor the infusion of lactated Ringer’s nor the combination of the two had any protective effect on the development of PEP. Patient-related factors such as recurrent acute pancreatitis (AP), chronic pancreatitis, previous PEP and the presence of biliary stricture also played no role.

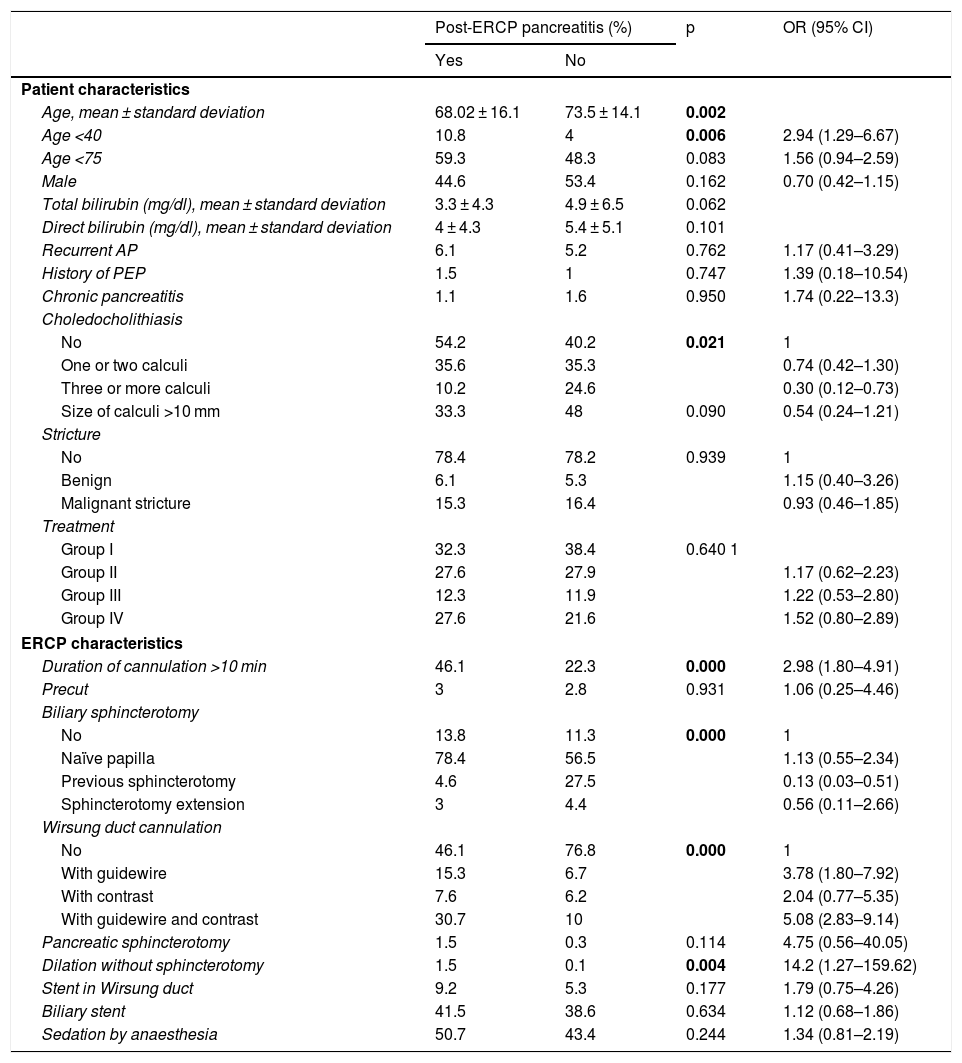

Table 2 shows the results of the bivariate analysis relating to the influence of the different factors studied on the likelihood of developing PEP. The presence of choledocholithiasis had a protective effect on the development of PEP (odds ratio [OR]: 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.42–1.30). The placement of the stent in the Wirsung duct had no influence (OR: 1.79; (95% CI: 0.75–4.26; p = 0.177). Related to the technique, the following factors increased the risk of developing PEP: cannulation of the pancreatic duct, multiplying the risk by 3.78 (95% CI: 1.80–7.92) when cannulation was done with a guidewire and by 5.08 (95% CI: 2.83–9.14) when both guidewire and contrast were used; pancreatic sphincterotomy, increasing the risk by 4.75 (95% CI: 0.56–40.05); duration of cannulation greater than 10 min, increasing the risk by 2.98 (95% CI: 1.80–4.91); biliary sphincterotomy in a naïve papilla, increasing the risk by 1.13 (95% CI: 0.55–2.34); and biliary dilation without sphincterotomy, increasing the risk by 14.28 (95% CI: 1.27–159.62). However, previous sphincterotomy had a protective effect, with OR: 0.13 (95% CI: 0.03−0.51), as did sphincterotomy extension, with OR: 0.56 (95% CI: 0.11–2.66) (Table 2).

Results of the bivariate analysis relating to the influence of the different factors studied on the likelihood of developing post-ERCP pancreatitis.

| Post-ERCP pancreatitis (%) | p | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age, mean ± standard deviation | 68.02 ± 16.1 | 73.5 ± 14.1 | 0.002 | |

| Age <40 | 10.8 | 4 | 0.006 | 2.94 (1.29–6.67) |

| Age <75 | 59.3 | 48.3 | 0.083 | 1.56 (0.94–2.59) |

| Male | 44.6 | 53.4 | 0.162 | 0.70 (0.42–1.15) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl), mean ± standard deviation | 3.3 ± 4.3 | 4.9 ± 6.5 | 0.062 | |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dl), mean ± standard deviation | 4 ± 4.3 | 5.4 ± 5.1 | 0.101 | |

| Recurrent AP | 6.1 | 5.2 | 0.762 | 1.17 (0.41–3.29) |

| History of PEP | 1.5 | 1 | 0.747 | 1.39 (0.18–10.54) |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.950 | 1.74 (0.22–13.3) |

| Choledocholithiasis | ||||

| No | 54.2 | 40.2 | 0.021 | 1 |

| One or two calculi | 35.6 | 35.3 | 0.74 (0.42–1.30) | |

| Three or more calculi | 10.2 | 24.6 | 0.30 (0.12–0.73) | |

| Size of calculi >10 mm | 33.3 | 48 | 0.090 | 0.54 (0.24–1.21) |

| Stricture | ||||

| No | 78.4 | 78.2 | 0.939 | 1 |

| Benign | 6.1 | 5.3 | 1.15 (0.40–3.26) | |

| Malignant stricture | 15.3 | 16.4 | 0.93 (0.46–1.85) | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Group I | 32.3 | 38.4 | 0.640 1 | |

| Group II | 27.6 | 27.9 | 1.17 (0.62–2.23) | |

| Group III | 12.3 | 11.9 | 1.22 (0.53–2.80) | |

| Group IV | 27.6 | 21.6 | 1.52 (0.80–2.89) | |

| ERCP characteristics | ||||

| Duration of cannulation >10 min | 46.1 | 22.3 | 0.000 | 2.98 (1.80–4.91) |

| Precut | 3 | 2.8 | 0.931 | 1.06 (0.25–4.46) |

| Biliary sphincterotomy | ||||

| No | 13.8 | 11.3 | 0.000 | 1 |

| Naïve papilla | 78.4 | 56.5 | 1.13 (0.55–2.34) | |

| Previous sphincterotomy | 4.6 | 27.5 | 0.13 (0.03–0.51) | |

| Sphincterotomy extension | 3 | 4.4 | 0.56 (0.11–2.66) | |

| Wirsung duct cannulation | ||||

| No | 46.1 | 76.8 | 0.000 | 1 |

| With guidewire | 15.3 | 6.7 | 3.78 (1.80–7.92) | |

| With contrast | 7.6 | 6.2 | 2.04 (0.77–5.35) | |

| With guidewire and contrast | 30.7 | 10 | 5.08 (2.83–9.14) | |

| Pancreatic sphincterotomy | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.114 | 4.75 (0.56–40.05) |

| Dilation without sphincterotomy | 1.5 | 0.1 | 0.004 | 14.2 (1.27–159.62) |

| Stent in Wirsung duct | 9.2 | 5.3 | 0.177 | 1.79 (0.75–4.26) |

| Biliary stent | 41.5 | 38.6 | 0.634 | 1.12 (0.68–1.86) |

| Sedation by anaesthesia | 50.7 | 43.4 | 0.244 | 1.34 (0.81–2.19) |

ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: PEP: post-ERCP pancreatitis.

We divided the patients into two groups according to their risk of developing PEP, in line with the criteria used by Elmunzer et al.8 We thus formed a high-risk group of 728 (38.4%) patients. In group I 34.9% of patients were at high risk, in group II this figure was 37.2%, in group III it was 44.1% and in group IV it was 43%. In this high-risk group, there were 39 PEP cases (60% of all PEP). The rate of PEP was 4%, 5.6%, 5% and 7.3% for group I, group II, group III and group IV, respectively. There were no significant differences between the groups (p = 0.501). When assessing the severity of the pancreatitis, there were fewer severe cases in groups II and IV compared to the groups with no treatment or lactated Ringer’s, but with no statistical significance (p = 0.078).

A logistic regression analysis was performed between variables relating to the patient and the technique which could potentially be confounding factors. Variables having shown statistical, or near-significant, differences were all taken into account, such as sex; age <40 years; duration of cannulation >10 min; use of diclofenac, lactated Ringer’s or diclofenac plus lactated Ringer’s; choledocholithiasis; pancreatic duct cannulation; dilation without sphincterotomy; pancreatic stent; precut; biliary sphincterotomy; and pancreatic sphincterotomy.

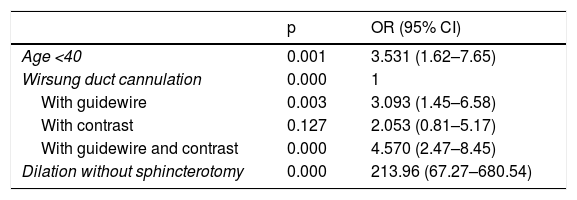

In our study, the only variables significantly related to the development of PEP were Wirsung duct cannulation (with guidewire, contrast or both; OR: 3.09 [95% CI: 1.45–6.58], OR: 2.05 [95% CI: 0.81–5.17] and OR: 4.57 [95% CI: 2.47–8.45], respectively) and dilation without sphincterotomy (OR: 213.96 [95% CI: 67.27–680.54]). The latter result may be misleading, given that we only had three patients who underwent this procedure. Being under 40 years of age is a factor that would increase the risk by 3.53 (95% CI: 1.62–7.65). Use of diclofenac, infusion of lactated Ringer’s or both had no influence (Table 3).

Significant results from the logistic regression analysis with patient-related and ERCP-related variables that could be confounding factors in the development of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

| p | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age <40 | 0.001 | 3.531 (1.62–7.65) |

| Wirsung duct cannulation | 0.000 | 1 |

| With guidewire | 0.003 | 3.093 (1.45–6.58) |

| With contrast | 0.127 | 2.053 (0.81–5.17) |

| With guidewire and contrast | 0.000 | 4.570 (2.47–8.45) |

| Dilation without sphincterotomy | 0.000 | 213.96 (67.27–680.54) |

ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

No other adverse effects were observed in the diclofenac-treated groups, and there was no volume overload in the groups treated with fluids. In group I there were eight cases of bleeding (1.1%), with 1.3% in group II, 1.8% in group III and 1.4% in group IV (p = 0.884). All bleeding episodes occurred after sphincterotomy. None required intensive care unit admission. There were 14 cases of perforation, 0.3% in group I, 1.3% in group II, 0.9% in group III and 0.7% in group IV (p = 0.201).

DiscussionThe results of this study show that none of the prophylactic measures we have implemented over time (rectal diclofenac or hydration with lactated Ringer’s) have led to a reduction in the number of cases of PEP. Although non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs9 and aggressive hydration11,12 are recommended separately as prophylactic measures for PEP, little is known about the possible benefits of the combination of these two measures. Using more than one tactic for preventing PEP may reduce this adverse effect.

Our results also show that this combined prophylactic strategy did not succeed in reducing PEP numbers in our setting.

To our knowledge, only two randomised, controlled studies have investigated the benefits of rectal hydration with indomethacin in PEP prophylaxis. The first study, by Mok et al.13 in 192 patients, found that those treated with lactated Ringer’s (1 l 30 min before ERCP) and rectal indomethacin 100 mg had a lower number of cases of PEP than the controls (1 l of saline plus placebo). The second study, conducted in 406 patients with choledocholithiasis, found that the combination of hydration with normal saline (1 l of saline two hours before ERCP and 2 l in the 16 h after the end of the procedure) and indomethacin significantly reduced the incidence of PEP compared to treatment alone or placebo.17 These results suggest a role for peri-procedural hydration in the prevention of PEP, but the small number of patients and the design of the intervention groups make it impossible to draw firm conclusions.

Unlike the study by Mok et al.,13 our study found no reduction in the number of cases of PEP in patients treated prophylactically with rectal diclofenac plus lactated Ringer’s. However, our study was different, as it was a mixed group and, furthermore, we treated patients with one prophylactic measure or another consecutively and compared them to a historical control group. We treated high-, medium- and low-risk patients. None of these groups showed a trend towards a lower number of cases of PEP.

Perhaps our results can be explained by the fact that we did not use aggressive hydration. We only used 200 ml/h of lactated Ringer’s during the procedure and for 4 h post-examination. These volumes are clearly lower than those used in other studies,11–13 but a decision was made to use these doses to avoid volume overload, as more than 50% of our patients were over 75 years of age and had multiple comorbidities. However, those who underwent Wirsung duct cannulation were administered an infusion of lactated Ringer’s of 500 ml/30 min.

Our results are in line with those published by Hajalikhani et al.,18 who, in their controlled study, found no reduction in PEP in 107 patients treated with diclofenac plus aggressive hydration with lactated Ringer’s (3 ml/kg/h during ERCP plus a bolus of 20 ml/kg/h at the end of the procedure and then 3 ml/kg/h for 8 h). In this case, the number of patients treated was very small and the incidence of PEP was very low.

A weak point of our study is that it is a mixed-cohort study with a retrospective historical cohort where some data may have been lost, and we have compared it with prospective cohorts. Another weak point to take into account is the doses of lactated Ringer’s solution we used, which are clearly lower than the similar studies we have mentioned, making comparisons difficult. Lastly, other limitations of our study are the small number of cases of PEP (65 compared to 1896 ERCP overall), which may limit its statistical power, and the low number of patients in groups iii and iv, which could explain the absence of significant differences in some of the comparisons made.

A strong point of our study is that ERCP was performed by the same two endoscopists throughout the study, so there could not have been much variation in the technique used and physicians in training were not involved.

Another strength is that it reflects a population having received care at a Spanish tertiary hospital and undergone ERCP, with patients at different degrees of risk for developing PEP.

In conclusion, in our study, neither rectal diclofenac given before ERCP nor hydration during and after ERCP led to a reduction in the number of cases of PEP. The combination of the two prophylactic measures in patients at high and low risk of PEP did not yield additional benefits or a decrease in the number or severity of cases of this complication. Other studies with greater statistical power would be necessary to assess this treatment.

Conflicts of interestNone of the article’s signatory authors have any conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: del Olmo Martínez ML, Velayos Jiménez B, Almaraz-Gómez A. Hidratación con Ringer Lactato combinado con diclofenaco rectal en la prevención de pancreatitis poscolangiopancreatografía retrógrada endoscópica. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:20–26.