The main clinical practice guidelines recommend endoscopy within 24h after admission to the Emergency Department in patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. However, it is a wide time frame and the role of urgent endoscopy (<6h) is controversial.

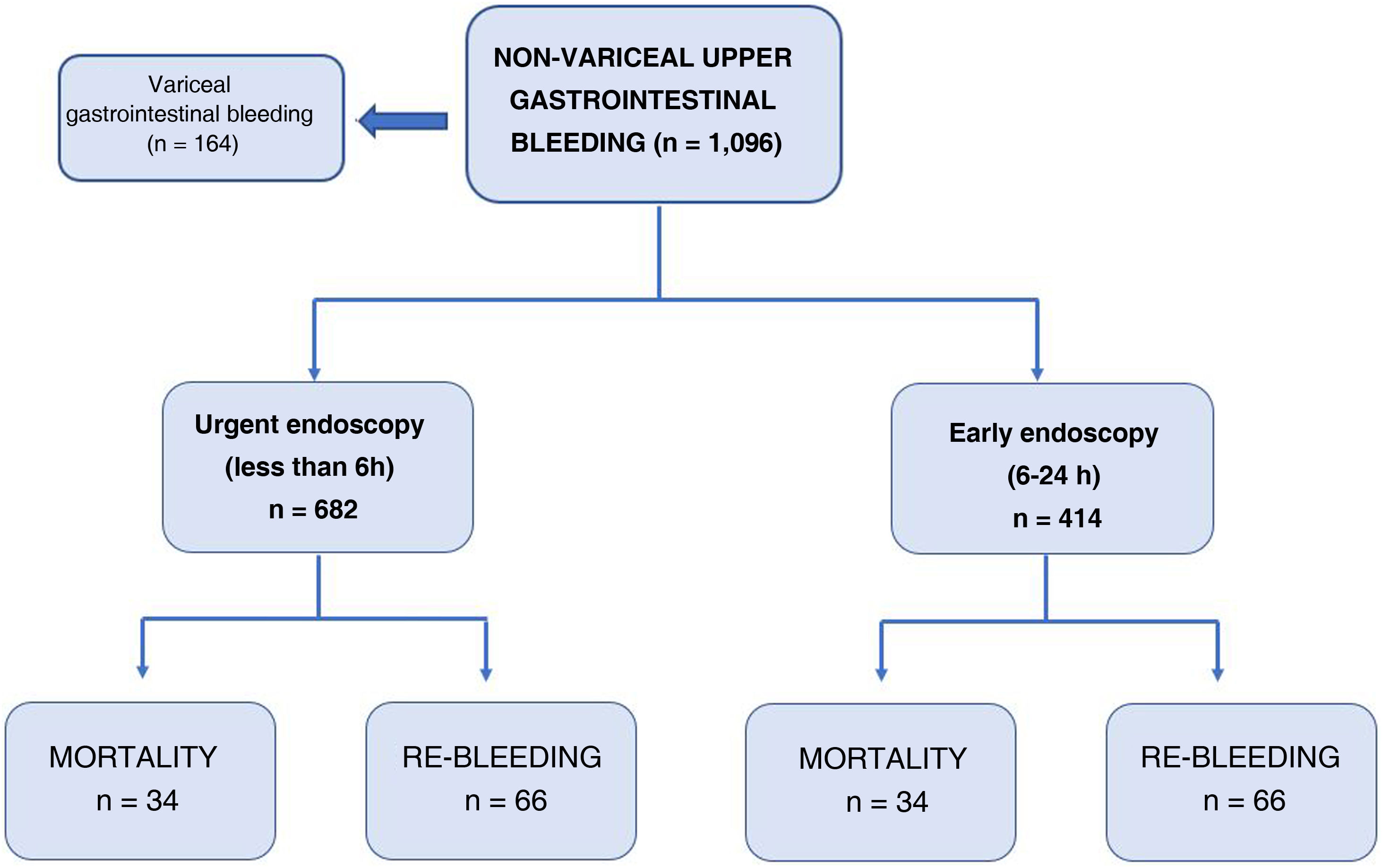

Material and methodsProspective observational study carried out at La Paz University Hospital, where all patients were selected, from January 1, 2015 to April 30, 2020, who attended the Emergency Room and underwent endoscopy for suspected upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Two groups of patients were established: urgent endoscopy (<6h) and early endoscopy (6−24h). The primary endpoint of the study was 30-day mortality.

ResultsA total of 1096 were included, of whom 682 underwent urgent endoscopy. Mortality at 30 days was 6% (5% vs. 7.7%, p=0.064) and rebleeding was 9.6%. There were no statistically significant differences in mortality, rebleeding, need for endoscopic treatment, surgery and/or embolization, but there were differences in the necesity for transfusion(57.5% vs. 68.4%, p<0.001) and the number of concentrates of transfused red blood cells(2.85±4.01 vs. 3.51±4.09, p=0.008).

ConclusionUrgent endoscopy, in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding, as well as the high-risk subgroup (GBS≥12), was not associated with lower 30-day mortality than early endoscopy. However, urgent endoscopy in patients with high-risk endoscopic lesions (Forrest I-IIB), was a significant predictor of lower mortality. Therefore, more studies are required for the correct identification of patients who benefit from this medical approach (urgent endoscopy).

Las principales guías de práctica clínica recomiendan la realización de endoscopia dentro de las 24horas posteriores a la admisión en Urgencias en pacientes con hemorragia digestiva alta no variceal. Sin embargo, es un margen de tiempo muy amplio y el papel de la endoscopia urgente (<6horas) es controvertido.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo observacional realizado en Hospital Universitario La Paz, donde son seleccionados todos los pacientes, desde el 1 de enero de 2015 hasta el 30 de abril de 2020, que acudieron a Urgencias y fueron sometidos a endoscopia por sospecha de hemorragia digestiva alta. Se establecieron dos grupos de pacientes: endoscopia urgente (<6horas) y precoz(6−24horas). El objetivo primario del estudio fue la mortalidad a los 30 días.

ResultadosUn total de 1096 fueron incluidos, de los cuales 682 fueron sometidos a endoscopia urgente. La mortalidad a los 30 días fue del 6% (5% vs. 7,7%, p=0,064) y del resangrado del 9,6%. No hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la mortalidad, resangrado, necesidad de tratamiento endoscópico, cirugía y/o embolización, pero sí en la necesidad de transfusión (57,5% vs. 68,4%, p<0,001) y el número de concentrados de hematíes transfundidos (2,85+/-4,01 vs. 3,51+/-4,09, p=0,008).

ConclusiónLa endoscopia urgente, en pacientes con hemorragia digestiva alta aguda, también el subgrupo de alto riesgo (GBS≥12), no se asoció con una mortalidad menor a los 30 días que la endoscopia precoz. Sin embargo, en los pacientes con lesiones endoscópicas de alto riesgo (Forrest I-IIB), fue un predictor significativo de menor mortalidad. Por lo tanto, se requieren más estudios para la identificación correcta de pacientes, que se beneficien de esta actitud médica (endoscopia urgente).

Acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a common cause of emergency care and hospital admission. It has an estimated annual incidence of 40–150/100,000 inhabitants with significant morbidity, socioeconomic costs and associated mortality.1 Despite significant progress in recent years, both from the point of view of medical and endoscopic treatment, mortality remains high, with results ranging from 2% to 14%,2–4 partly attributed to the ageing of the population and the associated comorbidity.

Initial treatment of these patients includes haemodynamic support, treatment with proton pump inhibitors, and antithrombotic/anticoagulant drug management.5 The next step is to perform a gastrointestinal endoscopy, the gold standard procedure which is essential for diagnosis and treatment.

The main clinical practice guidelines6–9 recommend that patients with suspected UGIB undergo endoscopy within 24h of admission to the emergency department, as this is associated with a shorter average length of stay, lower hospital costs and lower mortality.10–12 However, it is a very long time frame, and the ideal time to perform endoscopy in upper gastrointestinal bleeding remains controversial, it being essential to provide timely, appropriate treatment.

Different risk stratification scales have been developed to predict outcomes in patients with UGIB and identify those at high risk. The Glasgow-Blatchford Bleeding Score (GBS) stands out,13 showing greater predictive ability14 than the Rockall score (RS)15 or the AIMS65. The cut-off value of GBS for high-risk patients remains ambiguous, and different studies16,17 agree that a GBS result ≥12 is indicated to identify those patients who are at higher risk of requiring endoscopic treatment or blood product transfusion, re-bleeding, and death.

The role of urgent endoscopy (UE) (≤6h) in patients with UGIB, particularly in the subgroup of high-risk patients, remains controversial and the subject of intense debate. In recent years various studies have been published that offer contradictory results. In the retrospective cohort in the study by Cho et al.,18 with a total recruitment of 961 high-risk patients, defined by a GBS>7, UE was associated with lower mortality (1.6% vs. 3.8%, p=0.034). However, in the randomised clinical trial conducted by Lau et al.16 (n=516) the researchers report that UE (<6h from gastroenterologist consultation) was not associated with lower mortality (8.9% vs. 6.6%, p=0.34) at 30 days than early endoscopy (EE), but, as a major limitation, it excludes patients who remain haemodynamically unstable.

The aim of our study is to evaluate the role and clinical outcomes of UE (less than 6h after admission to the emergency department) in UGIB, as well as to identify the subgroup of high-risk patients who might benefit from this medical approach.

Material and methodsStudy design and objectivesThis was a prospective, observational cohort study, which included consecutively, from January 2015 to May 2020, all patients over 18 years of age who were seen at the emergency department of the University Hospital La Paz (HULP) [La Paz University Hospital] with suspected UGIB, and who underwent an endoscopy in the first 24h after their admission. Excluded from the study were those patients in whom there was no evidence of UGIB in endoscopy, those patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding of variceal origin, as well as those patients with endoscopy performed after 24h (Fig. 1).

The endoscopy time was classified according to the time interval between admission to the emergency department and the procedure, as follows: UE, less than six hours; EE, 6−24h. At our hospital, endoscopy is available 24h a day, seven days a week, and is subject to the decision of the gastroenterologist on duty.

The main variable of the study was mortality at 30 days of hospital admission, both in the total number of patients and in the subgroups of high-risk patients. The secondary variables studied were re-bleeding at 30 days, endoscopic treatment, blood product transfusion and the number of transfused units, mean hospital stay, adequate endoscopic visualisation, and the need for surgery and/or embolisation.

Data collection and definitionsThe following data were extracted from hospital medical records: age, sex, time of admission to the emergency department and time of endoscopy, heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), haemodynamic instability (defined by HR>100 and SBP<100), comorbidities, cirrhosis and/or malignancy (active oncological history), anticoagulant/antiplatelet drugs, and laboratory findings such as haemoglobin (Hb), INR, platelet count. In addition, the pre-endoscopic GBS and RS score was calculated.

Endoscopic data were also included, establishing the cause of bleeding and the type of treatment applied, with treatment failure defined as the persistence of bleeding despite having applied a treatment for haemostatic purpose.

High-risk patients are those with GBS≥12 at presentation in the emergency department or those with high-risk stigmata in endoscopy, defined by the presence of Forrest I-IIB,19 lesions, who benefit from the application of endoscopic haemostatic treatment.

In our study, Forrest classification was applied in patients with ulcerative pathology (gastric or duodenal), of either peptic or malignant aetiology, Cameron ulcers, surgical anastomotic ulcers, severe oesophagitis (grade III-IV), and Mallory-Weiss syndrome.

Re-bleeding was defined as a decrease in haemoglobin ≥2g/dl; new onset of haematemesis or haematochezia; or active bleeding seen on a new endoscopy. For patients with a first episode of re-bleeding, endoscopic intervention was the first treatment option, with embolisation or surgery as the second choice.

Statistical analysis and ethical considerationsQuantitative variables are represented as mean±standard deviation, and qualitative data are represented as absolute numbers and percentages. In the case of continuous variables, comparisons are made using Student's t and qualitative data are compared using the chi-square test (χ2). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

The results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression were summarised by estimating the odds ratio (OR) and its respective 95% confidence interval (CI). Of the baseline clinical characteristics, only those with a p<0.10 value, according to the univariate analysis, are considered for the multivariate model.

For survival calculations and a graphical representation, Kaplan-Meier statistical analysis is used. Calculations were performed using the SPSS Statistics 24 (IBM) program. The study was approved by the HULP Research Ethics Committee (Madrid, Spain).

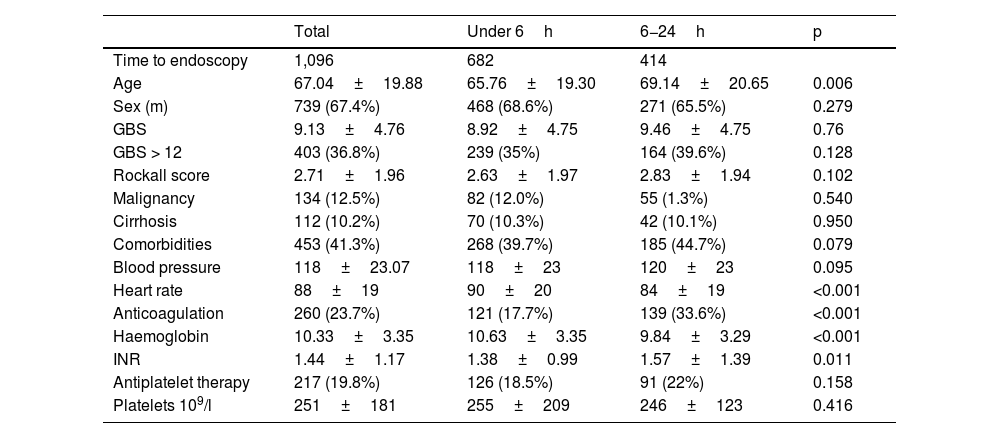

ResultsBaseline characteristics and endoscopic dataA total of 1,096 patients were included, of whom 682 (62.2%) underwent UE. The mean age was 67±19.8 years, with the UE group having a lower mean age (p=0.006). Melaena was the most common form of presentation (n=561, 51.2%).

The presence of comorbidities, malignancy and cirrhosis were observed in 41.3%, 12.5% and 10.2% of patients, respectively, with no differences between the two groups. A total of 260 patients were on anticoagulant therapy (23.7%), with a higher percentage in the EE group (p=0,001), the most commonly used anticoagulant being vitamin K antagonists(15.8%), with no differences in the use of antiplatelet drugs (n=217, 19.8%).

There were no significant differences in GBS or RS, BP or percentage of high-risk patients (35% vs. 39.6%, p=0.102) between groups. However, HR tended to be higher in patients in the UE group (90±20 vs. 84±19; p=0.001) (Table 1).

Baseline characteristics of the patients.

| Total | Under 6h | 6−24h | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to endoscopy | 1,096 | 682 | 414 | |

| Age | 67.04±19.88 | 65.76±19.30 | 69.14±20.65 | 0.006 |

| Sex (m) | 739 (67.4%) | 468 (68.6%) | 271 (65.5%) | 0.279 |

| GBS | 9.13±4.76 | 8.92±4.75 | 9.46±4.75 | 0.76 |

| GBS > 12 | 403 (36.8%) | 239 (35%) | 164 (39.6%) | 0.128 |

| Rockall score | 2.71±1.96 | 2.63±1.97 | 2.83±1.94 | 0.102 |

| Malignancy | 134 (12.5%) | 82 (12.0%) | 55 (1.3%) | 0.540 |

| Cirrhosis | 112 (10.2%) | 70 (10.3%) | 42 (10.1%) | 0.950 |

| Comorbidities | 453 (41.3%) | 268 (39.7%) | 185 (44.7%) | 0.079 |

| Blood pressure | 118±23.07 | 118±23 | 120±23 | 0.095 |

| Heart rate | 88±19 | 90±20 | 84±19 | <0.001 |

| Anticoagulation | 260 (23.7%) | 121 (17.7%) | 139 (33.6%) | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin | 10.33±3.35 | 10.63±3.35 | 9.84±3.29 | <0.001 |

| INR | 1.44±1.17 | 1.38±0.99 | 1.57±1.39 | 0.011 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 217 (19.8%) | 126 (18.5%) | 91 (22%) | 0.158 |

| Platelets 109/l | 251±181 | 255±209 | 246±123 | 0.416 |

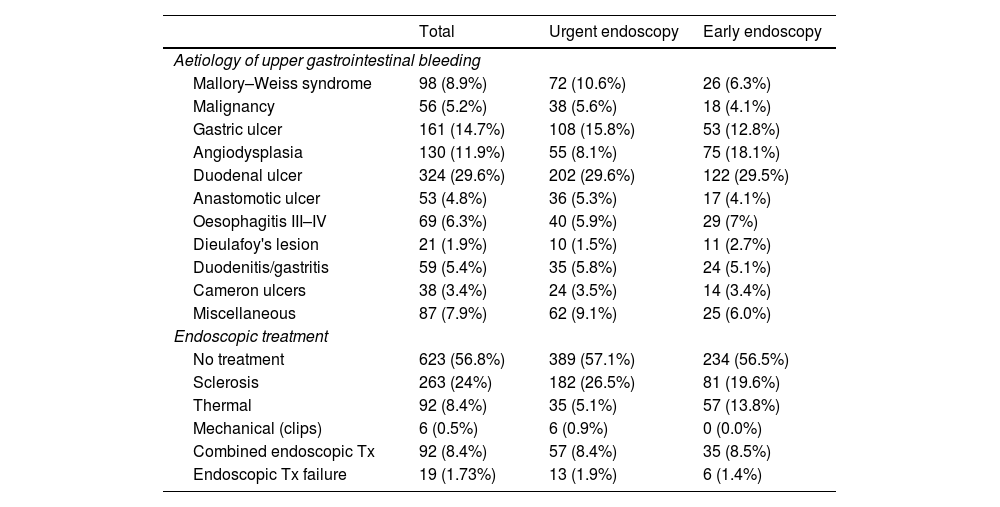

Endoscopic data are shown in Table 2. Among the most frequent causes of bleeding were gastric ulcers in 161 (14.7%) and duodenal ulcers in 324 (29.4%), followed by angiodysplasia/vascular ectasia in 130 (11.9%). The most commonly used endoscopic treatment was the use of sclerosing agents (24%), followed by the combination of two haemostatic methods (8.7%). In the UE group, endoscopic high-risk stigmata (Forrest I-IIB) were more often observed (50.1% vs. 39.5%; p=0.006). Despite this, there were no differences regarding the requirement for endoscopic treatment between the two groups, which is largely due to the higher prevalence of gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to vascular pathology (angiodysplasias, gastropathy, portal hypertension) in the EE group (8.1 vs. 18.1%).

Causes and treatment of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

| Total | Urgent endoscopy | Early endoscopy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aetiology of upper gastrointestinal bleeding | |||

| Mallory–Weiss syndrome | 98 (8.9%) | 72 (10.6%) | 26 (6.3%) |

| Malignancy | 56 (5.2%) | 38 (5.6%) | 18 (4.1%) |

| Gastric ulcer | 161 (14.7%) | 108 (15.8%) | 53 (12.8%) |

| Angiodysplasia | 130 (11.9%) | 55 (8.1%) | 75 (18.1%) |

| Duodenal ulcer | 324 (29.6%) | 202 (29.6%) | 122 (29.5%) |

| Anastomotic ulcer | 53 (4.8%) | 36 (5.3%) | 17 (4.1%) |

| Oesophagitis III–IV | 69 (6.3%) | 40 (5.9%) | 29 (7%) |

| Dieulafoy's lesion | 21 (1.9%) | 10 (1.5%) | 11 (2.7%) |

| Duodenitis/gastritis | 59 (5.4%) | 35 (5.8%) | 24 (5.1%) |

| Cameron ulcers | 38 (3.4%) | 24 (3.5%) | 14 (3.4%) |

| Miscellaneous | 87 (7.9%) | 62 (9.1%) | 25 (6.0%) |

| Endoscopic treatment | |||

| No treatment | 623 (56.8%) | 389 (57.1%) | 234 (56.5%) |

| Sclerosis | 263 (24%) | 182 (26.5%) | 81 (19.6%) |

| Thermal | 92 (8.4%) | 35 (5.1%) | 57 (13.8%) |

| Mechanical (clips) | 6 (0.5%) | 6 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Combined endoscopic Tx | 92 (8.4%) | 57 (8.4%) | 35 (8.5%) |

| Endoscopic Tx failure | 19 (1.73%) | 13 (1.9%) | 6 (1.4%) |

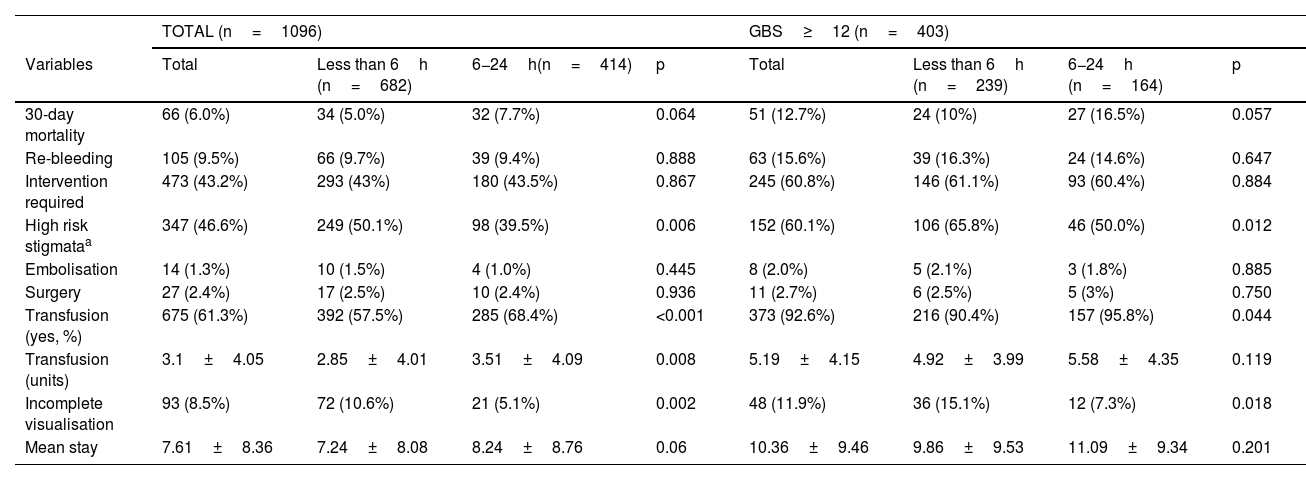

Total mortality at 30 days was 6% (n=66), being lower in the UE group (5% vs. 7.7%), although there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups (p=0.064). The re-bleeding rate was 9.5% (n=105), with no differences between the UE and EE groups (9.7% vs. 9.4%; p=0.888). The most common cause of re-bleeding was duodenal ulcer (45.7%). Surgery was performed in 27 patients (2.4%), with no differences between the two groups (2.5% vs. 2.4%; p=0.936) or in the need for endoscopic treatment (43% vs. 43.5%; p=0.867) or embolisation (1.5% vs. 1%; p=0.445).

UE was significantly associated with lower transfusion requirements. A lower percentage of patients required transfusion of blood products (57.5% vs. 68.4%, p<0.001) and a lower number of transfused units (2.85±4.01 vs. 3.51±4.09, p=0.008) compared with patients with EE. UE had, more frequently, incomplete endoscopic visualisation (10.5%, p=0.002). The mean length of stay showed a tendency to be higher in patients in the EE group (7.24±8.08 vs. 8.24±8.76; p=0.06), although this was not statistically significant (Table 3).

Total clinical results and patients with GBS≥12.

| TOTAL (n=1096) | GBS≥12 (n=403) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Total | Less than 6h (n=682) | 6−24h(n=414) | p | Total | Less than 6h (n=239) | 6−24h (n=164) | p |

| 30-day mortality | 66 (6.0%) | 34 (5.0%) | 32 (7.7%) | 0.064 | 51 (12.7%) | 24 (10%) | 27 (16.5%) | 0.057 |

| Re-bleeding | 105 (9.5%) | 66 (9.7%) | 39 (9.4%) | 0.888 | 63 (15.6%) | 39 (16.3%) | 24 (14.6%) | 0.647 |

| Intervention required | 473 (43.2%) | 293 (43%) | 180 (43.5%) | 0.867 | 245 (60.8%) | 146 (61.1%) | 93 (60.4%) | 0.884 |

| High risk stigmataa | 347 (46.6%) | 249 (50.1%) | 98 (39.5%) | 0.006 | 152 (60.1%) | 106 (65.8%) | 46 (50.0%) | 0.012 |

| Embolisation | 14 (1.3%) | 10 (1.5%) | 4 (1.0%) | 0.445 | 8 (2.0%) | 5 (2.1%) | 3 (1.8%) | 0.885 |

| Surgery | 27 (2.4%) | 17 (2.5%) | 10 (2.4%) | 0.936 | 11 (2.7%) | 6 (2.5%) | 5 (3%) | 0.750 |

| Transfusion (yes, %) | 675 (61.3%) | 392 (57.5%) | 285 (68.4%) | <0.001 | 373 (92.6%) | 216 (90.4%) | 157 (95.8%) | 0.044 |

| Transfusion (units) | 3.1±4.05 | 2.85±4.01 | 3.51±4.09 | 0.008 | 5.19±4.15 | 4.92±3.99 | 5.58±4.35 | 0.119 |

| Incomplete visualisation | 93 (8.5%) | 72 (10.6%) | 21 (5.1%) | 0.002 | 48 (11.9%) | 36 (15.1%) | 12 (7.3%) | 0.018 |

| Mean stay | 7.61±8.36 | 7.24±8.08 | 8.24±8.76 | 0.06 | 10.36±9.46 | 9.86±9.53 | 11.09±9.34 | 0.201 |

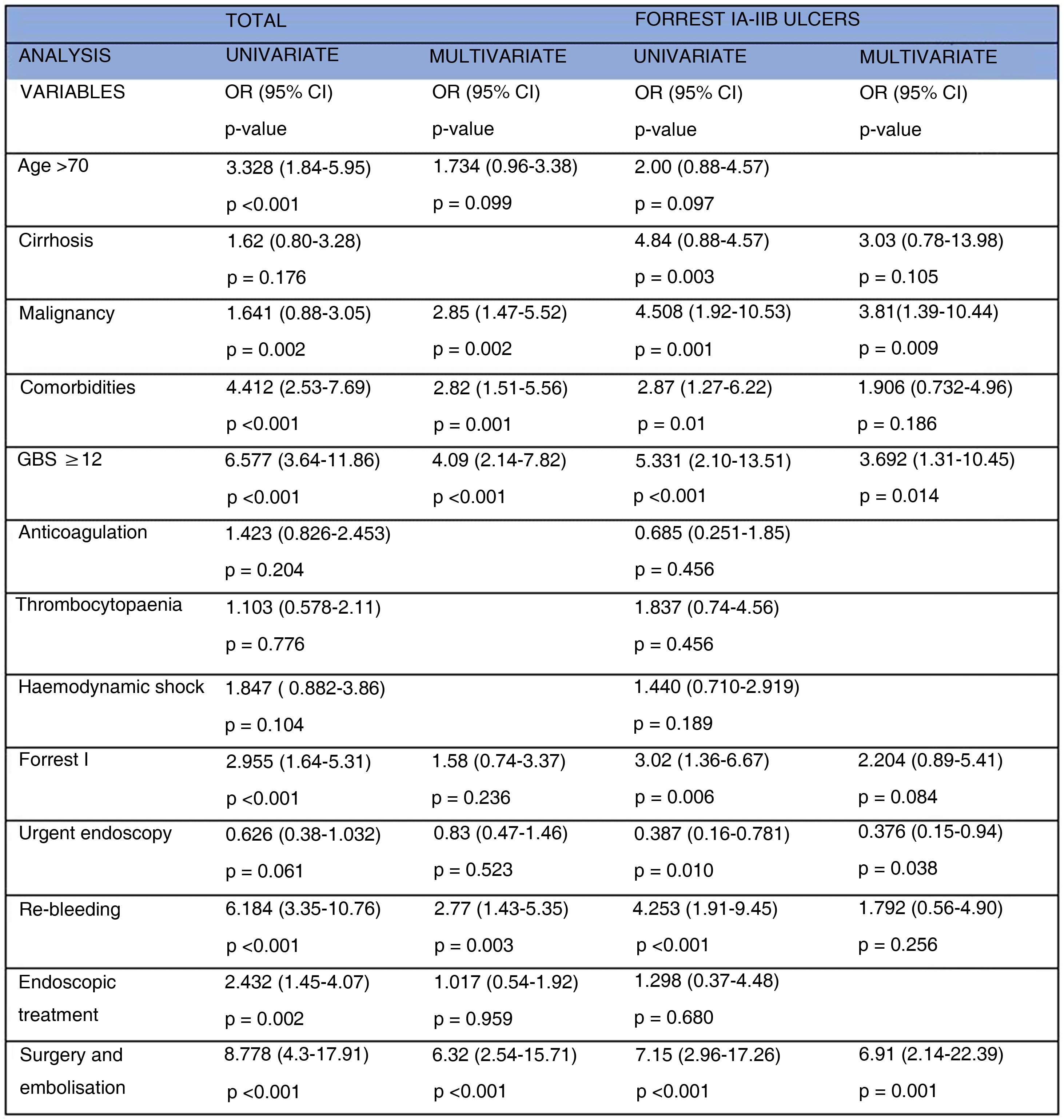

After adjusting between the different variables, in the multivariate analysis, malignancy (OR=1.641; 95% CI: 0.88–3.05; p=0.002), comorbidities (OR=4.412; 95% CI: 2.53–7.69; p<0.001), GBS≥12 (OR=6.577; 95% CI: 3.64–11.86; p<0.001), re-bleeding (OR=2.77; 95% CI: 1.43–5.35; p=0.003), and also the need for surgery and embolisation (OR=6.32; 95% CI: 2.54–15.71; p<0.001), remain independent predictors of mortality. The results of the univariate and multivariate analysis are presented in Fig. 2.

High-risk subgroupsGBS≥12This subgroup was made up of 403 patients (59% UE), with no differences in baseline characteristics, except for a higher percentage of patients with comorbidities (27.6% vs. 39.9%; p=0.017) and anticoagulated patients in the EE group (51.5% vs. 62.2%; p=0.033).

Mortality was 12.7%, 10% in the UE group (p=0.057), and re-bleeding was 15.6% (16.3% vs. 14.6%; p=0.647). There were no differences in the requirement for endoscopic treatment, surgery and/or embolisation, nor in the mean hospital stay, but a lower percentage of patients in the UE required a transfusion (90.4% vs. 95.8%, p=0.044).

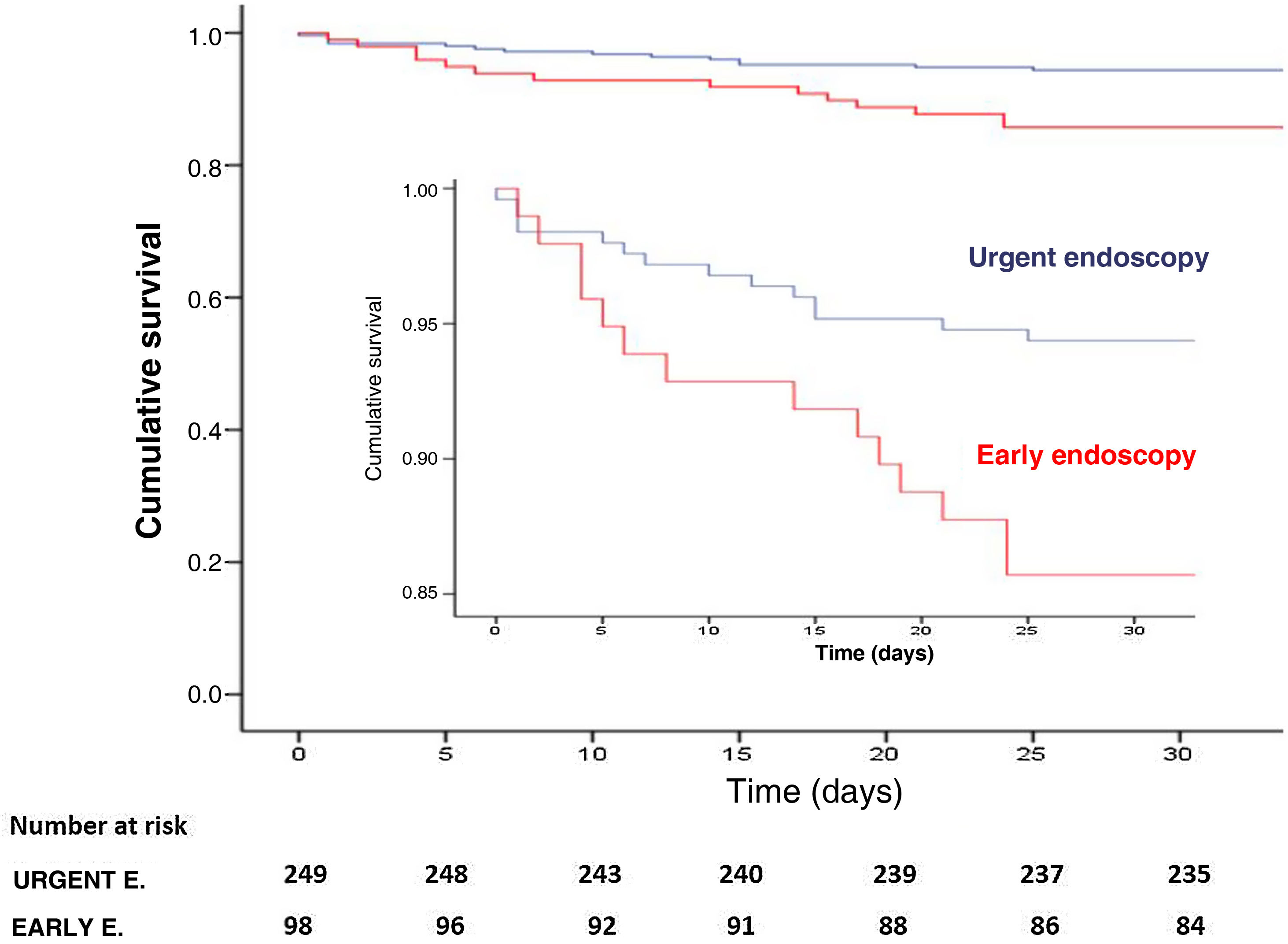

Forrest I-IIBThis subgroup consisted of 347 patients, 249 (71.7%) in the UE group, with no differences in the main baseline characteristics studied, except 35.7% of patients in the EE group were anticoagulated, compared to 18.9% in the UE group (p=0.001). The observed mortality was 28 patients (8.1%), lower in the UE group (5.6% vs. 14.3%), with statistically significant differences between groups (p=0.008). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed significantly better survival in those who underwent endoscopy within the first six hours (p=0.007) (Fig. 3). There were no differences in the re-bleeding rate (19.3%, p=0.0352), in the mean hospital stay (p=0.23), in the requirement for endoscopic treatment (86.3% vs. 92.9%; p=0.091), in surgery (p=0.857) and/or in embolisation (p=0.837). However, the UE group was associated with fewer patients undergoing transfusion (76.7% vs. 88.8%, p=0.011) and fewer transfused units (4.0±4.6 vs. 6.1±5.7; p<0.001). In addition, in multivariate analysis (Fig. 2) UE was a significant independent predictor of lower mortality [OR=0.376; 95% CI: 0.15−0.94; p=0.038).

DiscussionIn this cohort study of 1,096 patients with acute non-variceal UGIB, with a total mortality rate of 6.0% and re-bleeding rate of 9.4%, we found that UE did not lead to lower mortality, re-bleeding, endoscopic treatment, average stay, the requirement for surgery and/or embolisation than EE. However, there was a lower requirement for transfusion, with the clinical and financial implications that this entails, data which is consistent with the study by Lin et al.20 In addition, in percentage terms, we observed more deaths in the EE group, with an intergroup difference in mortality of 2.7%.

The subgroup analysis also found no differences in patients with GBS≥12. In contrast, in patients with Forrest I-IIB lesions, time to endoscopy was a significant independent predictor of mortality, with endoscopy in the first six hours being associated with lower mortality.

The role of UE in acute UGIB is still not clearly defined. For high-risk patients, an international consensus group does not make a recommendation for or against endoscopy in the first 6−12h.21

In recent years, several studies have been published investigating the influence of time to endoscopy on clinical outcomes in patients with UGIB, with very different conclusions. In some of these studies, UE demonstrated no clinical benefit,22–26 even being associated with worse outcomes.27,28 Of the latter we highlight the prospective study carried out by Laursen et al.29 in patients with haemodynamic instability (n=2,933), in which endoscopy performed within 6−24h was associated with lower in-hospital mortality (OR=0.73; 95% CI: 0.54−0.98).

On the contrary, it is worth mentioning the study by Lim et al.,30 in which UE is associated with lower mortality in the subgroup of high-risk patients (GBS≥12), but not in low-risk patients. The explanation is that only a quarter of patients with GBS≤12 had high-risk endoscopic stigmata, compared with 70% at high risk. As only a minority of low-risk patients would benefit from endoscopic treatment, urgent endoscopy would not be expected to improve clinical outcomes.

Based on this premise, we selected these patients with high-risk endoscopic stigmata using the Forrest classification (I-IIB), defined by the presence of lesions that benefit from the application of endoscopic therapy; this was corroborated by the data from our study, where the vast majority of patients required endoscopic treatment (88.3%). To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the results of this subgroup of patients, in which UE was statistically significantly associated with lower mortality, fewer patients undergoing transfusion and fewer transfused concentrates.

According to our results, the fact that the UE group had fewer transfusion requirements, both in the total number of patients and in the subgroups, can be explained, from our point of view, by the early application of endoscopic haemostatic treatment, with the consequent cessation of bleeding, which would have an impact on the Hb level and would result in lower transfusion needs.

Our study has several limitations. It is mainly an observational study, without randomisation. In addition, confounding factors related to the patient that were not studied cannot be excluded. However, to address possible differences between the groups, we demonstrated that GBS, the presence of comorbidity, malignancy, and other baseline characteristics were not significantly different in the groups. A greater number of patients in the EE group were anticoagulated. However, this anticoagulation was not significantly associated with mortality in the univariate analysis and is unlikely to be a confounding factor.

In conclusion, UE was not significantly associated with lower mortality, either in the total number of patients or in the GBS≥12 subgroup, but it was significantly associated with lower transfusion requirements. However, in patients with Forrest I-IIB lesions, UE was a significant independent predictor of lower mortality. The role of UE in non-variceal UGIB is still under discussion, and more randomised studies are needed to adequately identify patients, in a pre-endoscopic manner, who may benefit from this medical approach.

FundingNo funding has been received for the completion of this work.

Author contributionJavier Lucas Ramos: Research, Data collection, Drafting, Editing.

Jorge Yebra Carmona: Research, Data collection.

Irene Andaluz García: Research, Data collection.

Marta Cuadros Martínez: Data collection.

Patricia Mayor Delgado: Data collection.

Maria Ángeles Ruiz Ramírez: Data collection.

Joaquin Poza Cordón: Methodology, Design, Editing.

Cristina Suárez Ferrer: Methodology, Design, Editing, Research.

Ana Delgado Suárez: Research, Editing.

Nerea Gonzalo Bada: Drafting-revision.

Consuelo Froilán Torres: Drafting-revision.

Conflicts of interestThe authors confirm that there is no financial or personal relationship with other individuals or organisations that could give rise to a conflict of interest in relation to this study.