The use of herbal products and dietary supplements (HDS) carries a potential risk of liver toxicity. Data on HDS consumption among patients attending liver disease clinics remain unexplored.

ObjectiveTo determine the frequency, types and reasons for HDS consumption in patients attending a specialized liver disease outpatient clinic.

MethodsProspective study including consecutive patients attending the hepatology outpatient clinic at the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona from June 2023 to October 2023. Following a standard medical visit, a trained nurse conducted a structured interview to assess HDS consumption.

ResultsA total of 150 patients were included, with a median age of 59 (IQR: 49–67) and male predominance (56%, n=84). Only 12 patients (8%) reported HDS consumption during a standard medical interview, while the number increased to 92 (61%) after nurse-led structured interview. The primary reasons for dietary supplements use included vitamin supplementation (43%), fitness improvement (10.5%) and hair/nail health (10.5%). For herbal products, the most common reason for use was pleasure (73%). Reported HDS products with potential hepatotoxicity (levels A and B) were green tea (n=16), turmeric with black pepper (n=11), aloe (n=2), greater celandine (n=1) and black cohosh (n=1).

ConclusionHDS use is highly prevalent among patients with liver disease, but a structured interview is crucial to detect their consumption, as they usually forget spontaneous reporting. Importantly, a significant proportion of these products carry a risk of hepatic toxicity, underscoring the need for increased patient education and clinical vigilance.

El uso de productos de herbolario y suplementos dietéticos (HDS, por sus siglas en inglés) conlleva un riesgo potencial de toxicidad hepática. Sin embargo, los datos sobre el consumo de HDS en los pacientes que acuden a consultas de enfermedades hepáticas siguen siendo escasos.

ObjetivoDeterminar la frecuencia, los tipos y los motivos del consumo de HDS en los pacientes que acuden a una consulta ambulatoria especializada en enfermedades hepáticas.

MétodosEstudio prospectivo que incluyó a los pacientes consecutivos atendidos en la consulta externa de Hepatología del Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, entre junio y octubre de 2023. Tras una visita médica estándar, una enfermera especializada realizó una entrevista estructurada para evaluar el consumo de HDS.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 150 pacientes, con una edad mediana de 59 años (RIC: 49-67) y predominio masculino (56%, n=84). Solo 12 pacientes (8%) informaron del consumo de HDS durante la entrevista médica estándar, mientras que la cifra aumentó a 92 (61%) tras la entrevista estructurada realizada por la enfermera. Los principales motivos para el uso de suplementos dietéticos fueron: suplementación vitamínica (43%), mejora del rendimiento físico (10,5%) y salud del cabello/uñas (10,5%). En cuanto a los productos de herbolario, el motivo más común fue el placer (73%). Los productos HDS reportados con potencial hepatotoxicidad (Niveles A y B) fueron: té verde (n=16), cúrcuma con pimienta negra (n=11), aloe (n=2), celidonia mayor (n=1) y Cimifuga (cohosh negro) (n=1).

ConclusiónEl uso de HDS es muy prevalente en los pacientes con enfermedades hepáticas, pero es necesaria una entrevista estructurada para detectar su consumo. Es importante destacar que una proporción significativa de estos productos conlleva un riesgo de toxicidad hepática, lo que subraya la necesidad de una mayor educación al paciente y vigilancia clínica.

The use of herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) has become increasingly widespread in clinical practice, partly due to the perception that these products, being natural, pose minimal health risks. Additionally, their accessibility – whether online or in specialized shops – contributes to their growing popularity.1,2 From multivitamins to traditional herbal remedies, patients frequently incorporate these supplements into their daily routines and do not acknowledge their potential risks.

Dietary supplements encompass a broad spectrum of products, including vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and some botanical extracts. They are typically marketed as dietary complements, aiming to fill nutritional gaps or promote overall health.3 Herbal supplements, derived from plant sources, have been used for centuries in traditional medicine worldwide. With the resurgence of interest in natural remedies, their popularity has increased among patients seeking alternative approaches to various health conditions. While some herbal products have shown therapeutic potential, the lack of standardized manufacturing processes and limited regulatory oversight raise concerns regarding product purity, potency, and safety.4,5 This is particularly relevant in hepatology, as certain natural products have been associated with hepatotoxicity.6–10 Although HDS accounts for only 4% of liver injury cases recorded in the Spanish Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI) registry,11 this figure is probably higher due to the common underreporting of patients. Moreover, some studies have observed elevated transplantation rates in DILI cases induced by complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).6

The efficacy, safety, and potential interactions of these products with prescribed medications12 are often unknown to patients and, in some cases, their physicians – who may be unaware that the patient is consuming them. This underscores the importance of an active search to explore the consumption of these products among patients in our clinical setting.13 In this context, nurses can play a key role14 by educating patients about the potential adverse effects of herbal supplements and ensuring their accurate recording in medical reports. This proactive approach enhances the early detection of hepatotoxicity-related signs and symptoms, enabling timely intervention and improving patient safety.15

In this study, we aimed to investigate the prevalence of HDS use among patients with chronic liver disease attending an outpatient clinic. Additionally, we evaluated the role of specialized nursing staff in identifying the use of these products and assessing potential safety concerns.

Patients and methodsPatients and study designWe prospectively included consecutive patients attending a liver outpatient clinic at Hospital Clinic (Barcelona) between June and October 2023. Patient inclusion was based on their attendance at the clinic and the feasibility of conducting a structured interview within the time constraints of routine clinical care. All eligible patients agreed to participate in the structured interview. It is also important to note that our clinics are enriched with patients with viral hepatitis, reflecting the logistical structure and referral patterns of our center. During a standard medical visit, the attending liver disease specialist assessed the patients’ clinical status and relevant medical history, including concurrent medications. After the physician's consultation, a specialized nurse conducted a structured interview focused on assessing additional HDS use.

During the interview, the nurse (EC) documented whether the patient was actively consuming any type of HDS. If the response was positive, patients were further questioned about their reasons for HDS use, frequency of intake, and knowledge of the ingredients contained in the product. Consumption frequency was categorized as daily (at least once per day), weekly (at least once per week), or occasional (less than once per week). The details of this interview are presented in Supplementary Material. Regarding product classification we considered herbal consumption when patients consumed non processed herbal products (acquired as herbal medicinal products for infusion). All other products (including herbal formulations manufactured to be used as dietary supplements) were classified as supplement consumption.

The probability of hepatotoxicity was assessed using the Livertox Likelihood scale,16 that estimates whether a medication is a cause of liver injury. The scale categorizes risk into five levels, from A (well-established cause) to E (no known association with liver injury).

Additionally, we collected epidemiological data (age, sex, and country of origin) and clinical variables (type of liver disease and chronic prescribed medications).

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were expressed as n (%) while quantitative variables were presented as median with interquartile range (P25–P75). Group comparisons were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at a two-sided p value of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

EthicsThe study obtained approval from by the Hospital Clínic Ethics Committee (Code HCP HCB/2024/1312) and was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. Patients’ data were pseudonymized and all patients provided written informed consent before inclusion.

ResultsA total of 150 patients were included in the study. The median age was 59 (49–67) years and 84 (56%) were male. Regarding geographic origin, most individuals (73%) were born in Europe; 12% were of Asian origin. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C accounted for 37.5% and 36% of liver disease etiology, respectively. The main characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients (n=150) included in the study.

| Characteristics | Total cohort(n=150) | No consumption of HDS(n=58) | Consumption of HDS(n=92) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59 (49–67) | 58 (46–67) | 59 (49–68) | 0.87 |

| Biological sex | ||||

| Male | 84 (56%) | 38 (45%) | 46 (55%) | 0.06 |

| Female | 66 (44%) | 20 (30%) | 46 (70%) | |

| Geographic origin | ||||

| European | 110 (73%) | 44 (40%) | 66 (60%) | 0.91 |

| Asian | 18 (12%) | 7 (39%) | 11 (61%) | |

| African | 13 (9%) | 4 (31%) | 9 (69%) | |

| American | 9 (6%) | 3 (33%) | 6 (67%) | |

| Liver disease origin | ||||

| HCV-related | 54 (36%) | 18 (33%) | 36 (67%) | 0.37 |

| HBV-related | 56 (37.5%) | 20 (36%) | 36 (64%) | |

| MASLD | 11 (7.5%) | 5 (45%) | 6 (55%) | |

| Others* | 29 (19%) | 15 (52%) | 14 (48%) | |

| Chronic prescription of medication | ||||

| No | 33 (22%) | 10 (30%) | 23 (70%) | 0.26 |

| Yes | 117 (78%) | 48 (41%) | 69 (59%) | |

| 1 drug | 32 (27%) | 12 (37%) | 20 (63%) | |

| 2 drugs | 22 (19%) | 4 (18%) | 18 (82%) | |

| 3 or more drugs | 63 (54%) | 32 (51%) | 31 (49%) | |

Abbreviations: HCV: hepatitis C virus; HBV: hepatitis B virus; MASLD: metabolic associated steatotic liver disease.

According to the medical history documented by the hepatologist during the standard interview, only 12 (8%) patients reported the use of non-prescription medications in addition to their pharmacological therapies. After a structured interview conducted by the trained nurse, 92 (61%) patients admitted to consuming either herbal products (n=40, 43.5%), dietary supplements (n=24, 26%) or both (n=28, 30.5%).

The reasons for HDS consumption varied between herbal products and dietary supplements. Among herbal products users, the majority of patients (n=53, 73%) reported their use for pleasure, with no specific health concern identified. In a smaller proportion of cases, herbal products were used for specific health conditions, including joint pain (n=3, 4%), lipid control (n=3, 4%), weight loss (n=3, 4%), hepatic “detoxification” (n=2, 3%), digestive symptoms (n=2, 3%) or others (n=7, 9%). Regarding dietary supplements, the most common reasons for use included vitamin supplementation (n=25, 43%), fitness improvement (n=6, 10.5%), hair/nail health (n=6, 10.5%), joint/bone pain (n=4, 7%), liver “detoxification” (n=3, 5%), menopausal symptoms (n=3, 5%), herpes treatment (n=2, 3%) and others (n=9, 16%). Notably, 38% of patients reported using more than one product.

Most dietary supplements (90%) and a significant part of herbal products (26%) contained multiple components. When patients were asked about their knowledge of the components present in dietary supplements, 71% were unaware, with a similar proportion regarding herbal products (60%).

Variables associated with HDS consumption and patterns of HDS consumptionA total of 92 (61%) patients reported consuming HDS (Table 1). When analyzing variables associated with consumption, females showed a trend toward higher consumption (70%) than males (55%, p=0.06). Geographic origin categorized as European, Asian, African, and American, was comparable between those who consumed and did not consume HDS (p=0.91). Additionally, intake of HDS did not differ among different liver disease etiologies (p=0.37).

To assess potential interactions with chronic medications, we found that 78% of participants were taking at least one prescribed drug (27% were taking one medication, 19% were taking two, and 54% were taking three or more). However, we did not find significant differences in the prevalence of HDS use between those patients on prescription medications and those who were not (59% vs. 70%, p=0.26). A detailed summary of these data is presented in Table 1.

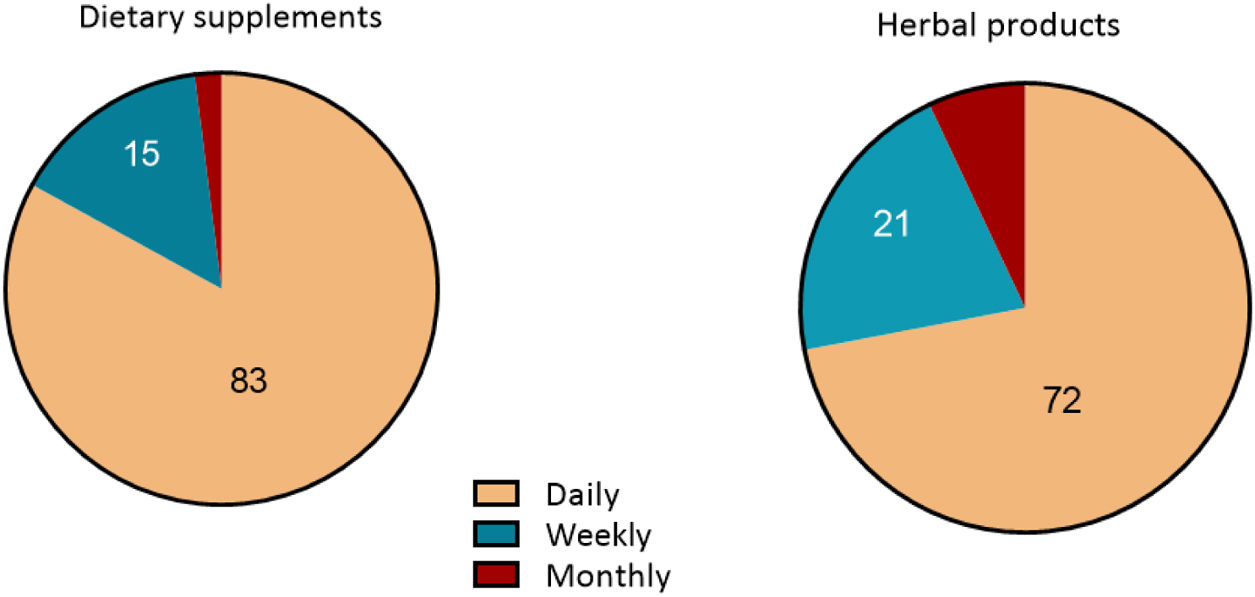

The analysis of HDS consumption patterns revealed that daily use was the most prevalent among dietary supplement users (43 patients, 83%), followed by weekly consumption (8 patients, 15%). Similarly, for herbal products, daily consumption was the predominant pattern (49 patients, 72%), followed by weekly consumption (14 patients, 21%) (Fig. 1).

Hepatotoxicity risk of HDS productsIn this study, a total of 32 patients (35%) were identified as being at risk of hepatotoxicity due to HDS consumption. According to the LiverTox Likelihood score, 16 patients (50%) were classified as well-established hepatotoxicity risk (Grade A), while 10 patients (31%) and 6 patients (19%) were categorized as highly probable (Grade B) and probable (Grade C), respectively. The most commonly used HDS products with potential hepatotoxicity were green tea (Camellia sinensis) (n=16), turmeric with black pepper (Curcuma longa with Piper nigrum) (n=11), ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) (n=2), aloe (Aloe vera) (n=2), horsetail (Equisetum arvense) (n=2), red yeast rice (Monascus purpureus) (n=2), valerian (Valeriana officinalis) (n=2), and clove (Syzygium aromaticum) (n=2). Black cohosh (Actaea racemosa) (n=1) was implicated in a case of elevation of transaminases in one of the patients in this study. Table 2 provides a detailed summary of the hepatotoxicity data reported in LiverTox for the identified compounds and products.

HDS compounds with potential hepatotoxicity.

| Compounds | Product | No. of patients* | LiverTox score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary supplements | |||

| Black cohosh | CimiNocta® | 1 | A |

| Aloe vera | Collagen capsulesAloe vera supplement | 2 | B |

| Turmeric** | DPR®Power Chocofit® | 2 | B |

| Ashwagandha | N19 Stress Control®***Gendiet Vital | 2 | C |

| Valerian | N19 Stress Control® | 1 | C |

| Caffeine (energy drink) | Energy gel® | 1 | C |

| Orlistat | Orlistat capsules | 1 | C |

| Horse chestnut | Horse chestnut capsules | 1 | D |

| Chondroitin-Glucosamine | MSM Condrotin-Glucosamin® | 2 | D |

| Saw palmetto | MartiDerm® capsules | 1 | D |

| Spirulina | Multivitamin complex | 1 | D |

| Echinacea | Pilexil anti-hair loss® | 1 | D |

| Creatine**** | Creatine monohydrate | 3 | ** |

| Herbal products | |||

| Green tea | Green tea infusion (13)Turmeric tea (1)Fat-burning tea (1)Fasting infusion (laboratories Replantea) (1) | 16 | A |

| Turmeric and turmeric with black pepper** | Turmeric (6)Turmeric with black pepper capsules or infusions (3) | 9 | B |

| Greater celandine | Infusion | 1 | B |

| Valerian | Infusion | 1 | C |

| Red yeast rice | Infusion | 2 | C |

| Horsetail | InfusionFat-burning tea | 2 | C |

| Clove | Curcuma teaYogi Tea Detox® | 2 | C |

| Echinacea | Infusion | 1 | D |

Our findings reveal a high prevalence (over 60%) of HDS consumption among patients attending hepatology outpatient clinics, with 26% using dietary supplements, 43.5% consuming herbal products and 30.5% both. Although data on HDS consumption in patients with chronic liver diseases are scare,17 our finding suggest that HDS consumption in patients with liver disease is even higher than in the general population. Moreover, recent data indicated that most patients do not consult with their healthcare providers before initiating supplementation.17 Our data reveal that a structured interview is clearly more efficient in detecting the use of such products, which is commonly overlooked by physicians during a regular patient consultation, probably due to lack of time or sufficient information. The crucial role of nurses in detecting HDS use and advising against a potential risk of liver injury or interactions with prescribed drugs has been analysed in some studies.14,15

A key concern arising from our data is the significant proportion of HDS products that are well documented as potentially causing liver injury, which is particularly concerning for patients with chronic liver disease. Although only one case of herb-induced liver injury (HILI) was identified during the study period, it is notable that around 50% of the HDS products reported in our cohort were classified as either well-established (Category A) or highly probable (Category B) causes of liver injury, according to the LiverTox classification.16 This hepatotoxic potential remains largely unrecognized by patients, leading to a lack of consultation with healthcare professionals regarding supplement use.18 Moreover, some HDS are recommended by healthcare professionals due to a perceived safety, based on its natural origin. Among them we find red yeast rice (stands out as a common supplement), which contains statin-like compounds19 that may contribute to idiosyncratic liver damage. Similarly, black cohosh is commonly recommended by healthcare professionals to control menopause symptoms.20 Other supplements with hepatotoxic potential include ashwagandha, regularly used as an adaptogen for stress and anxiety.21 Both have been linked to elevated transaminase levels, further highlighting the potential liver toxicity of certain widely used supplements.13,22,23

Regarding herbal infusions, green tea, derived from the leaves of the C. sinensis plant has been primarily consumed for weight loss, although evidence supporting its beneficial effects remains limited.24 Registry-based data show that HDS are responsible for 8% and 4% of liver toxicity cases reported in the Latin American25 and Spanish DILI Networks,11 respectively. Notably, green tea (C. sinensis) was the most frequently consumed herb in our cohort and also a leading cause of HILI in both registries. Most cases of hepatotoxicity associated with C. sinensis have been linked to the consumption of concentrated extracts (such as ethanolic catechin preparations or supplements), that can deliver up to 1000mg/day of catechins. This dosage is significantly higher than the amount found in a typical green tea infusion, which helps explain the increased incidence of toxicity in these cases.26

Most of our patients reported to consume HDS on a daily basis, which also indicates a long-term use. The latter poses a potential risk of interaction with prescription drugs. Although only a few herbal compounds, such as St. John's wort, are clearly known to interact with drugs, commonly consumed herbal dietary supplements (HDS) like chamomile, green tea, and Cat's claw have also been shown to influence the effectiveness and safety of prescription medications.12 This highlights the importance of integrating a detailed assessment of HDS consumption into the standard medical history, to better identify potential risks and interactions. Although some patients in our cohort reported the use of chamomile, it was not included in the analysis of potentially hepatotoxic supplements, as it is not classified as hepatotoxic according to the LiverTox database. This may explain its absence from the detailed discussion, despite being a widely used herbal product.

Our study has several strengths, including its prospective design and the use of a structured interview to identify herbal dietary supplement (HDS) use, which enhances the validity of our findings. The results underscore the importance of thoroughly assessing HDS use in clinical practice and highlight the crucial role of nursing staff in detecting potentially hepatotoxic products. However, some limitations should be noted. First, 32 patients reported consuming only herbal infusions, primarily green or black tea, which many individuals do not typically consider as herbal supplements, despite the potential hepatotoxic risks associated with green tea. This could have led to an overestimation of HDS prevalence. Second, our patient population is not fully representative of all individuals with liver disease, as it was specifically enriched with patients suffering from chronic hepatitis B and C. Third, although patient recruitment was prospective and attempted to be consecutive, inclusion ultimately depended on the availability of time during routine outpatient visits to conduct the structured interview. As a result, our sample represents a convenience sample, which may introduce a selection bias although it is unlikely to limit the generalizability of our findings to broader populations with liver disease.

In conclusion, the findings of this study highlight the high prevalence of HDS use and the essential role of advanced practice nursing in identifying and assessing supplement consumption, particularly in patients with underlying liver disease. However, it is important to recognize that our study benefited from the involvement of advanced-trained nursing staff, which may not be available in many hepatology units. Furthermore, widespread consultation overcrowding can severely limit the time available for conducting structured interviews about herbal product use. These factors should be considered when applying our findings to other clinical settings and further support the need for specialized nursing staff in liver outpatient clinics.

CRediT authorship contribution statementEC, AP and XF participated in the concept and design of the study, review and analysis of data, and writing and editing of the manuscript. The rest of the authors participated in the review and analysis of data and in the editing of the manuscript.

Ethical considerationsAll patients provided written informed consent before inclusion.

FundingNo financial support was received for this work.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declared no competing interests for this work.