Hypereosinophilia is a rare finding defined as an absolute eosinophil count >1500/µl. Eosinophilia can cause infiltration in different organs, with liver and gastrointestinal tract involvement being the most common.1 The purpose of this letter to the editor is to describe hepatic eosinophilic infiltration (HEI) in the context of hypereosinophilic syndrome secondary to Strongyloides stercoralis infection.

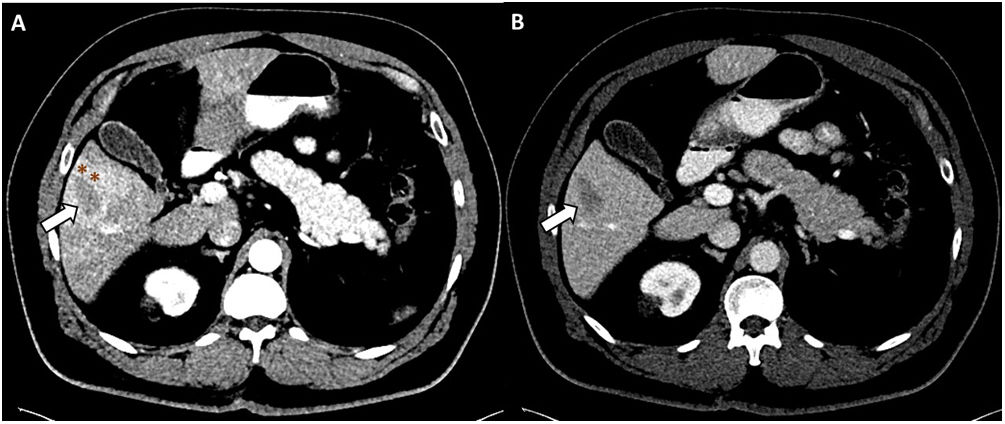

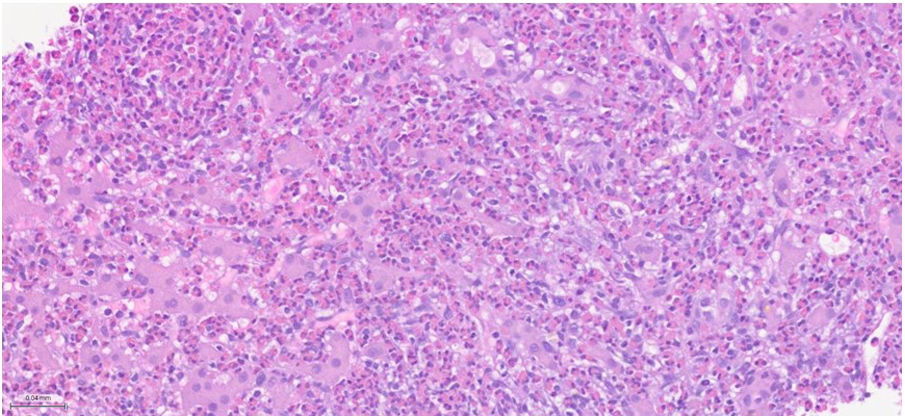

This was a 62-year-old male, residing in Africa, with a history of left partial nephrectomy for clear cell carcinoma, who attended a urological check-up asymptomatic. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen was performed, showing a hypointense lesion measuring 29 mm in diameter in segment V of the liver, and abnormal perfusion (Fig. 1). Laboratory tests showed hypereosinophilia of 1840/µl with no other findings. Suspecting metastasis, a liver biopsy was performed, revealing sinusoidal infiltration of eosinophils (Fig. 2), for which Infectious Diseases were asked to assess. A microbiological study was carried out with serology for: schistosomiasis, amoebiasis, anisakiasis, cysticercosis, strongyloidiasis, fascioliasis, hydatidosis and visceral larva migrans. A thick blood smear was also obtained, with no evidence of pathogens, as with the examination of faeces for parasites. The serology results were negative, except for IgG strongyloidiasis, which was positive (index: 4.337).

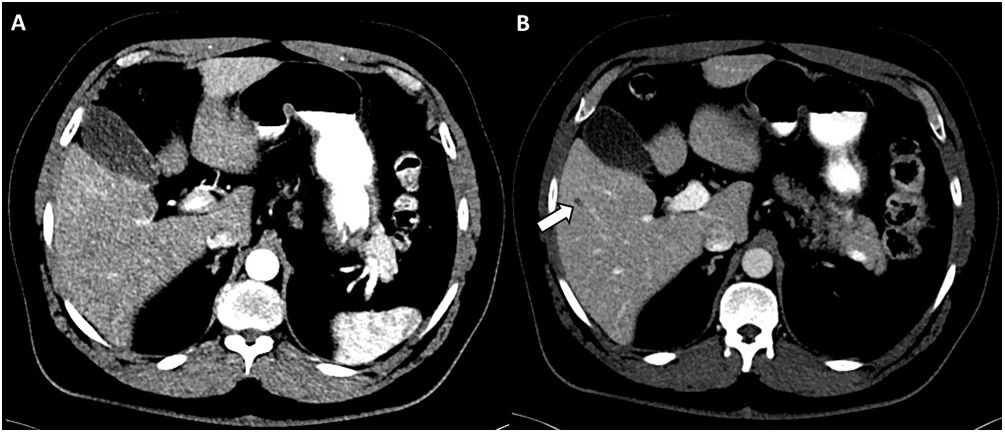

After ruling out Loa loa coinfection by serology, the patient was started on ivermectin 200 µg/kg for two days. At follow-up four months later, CT of the abdomen to monitor for liver damage showed resolution of the focal lesion in segment V (Fig. 3) and analysis showed return to normal of the patient's eosinophil count (290/µl).

Computed tomography of the abdomen obtained after intravenous administration of contrast in arterial (A) and portal (B) phases. Virtual resolution of the liver lesion identified in the previous scan. Only a very small hypodense lesion persists in the portal phase, which in the current study seems cystic in nature (white arrow), with a residual appearance.

HEI can manifest with radiological findings suggestive of neoplasia, so malignancy has to be ruled out.2 CT images of HEI are usually of small, poorly defined, hypointense lesions, more noticeable in the portal phase. The presence of a liver lesion associated with hypereosinophilia is suggestive of HEI. The combination of clinical and laboratory data may be enough to distinguish an HEI from a malignant lesion. In addition, in our case, the epidemiological risk, normal liver function tests, and the absence of elevated inflammatory parameters made the diagnosis of HEI more likely. Biopsy could have been saved for the event of not responding to anthelmintic treatment or the case of malignancy being strongly suspected.3 The most common causes of hypereosinophilia include parasitic infections, hypersensitivity reactions, connective tissue diseases, vasculitis, cancers and paraneoplastic syndromes. Some of the most common parasitic infections are caused by: Toxocara canis, Fasciola hepatica, Clonorchis sinensis, Paragonimus westermani, Taenia solium and S. stercoralis.3

Strongyloidiasis is an infection caused by the helminth S. stercoralis, which is able to complete its life cycle inside the human host. Approximately 75% of all infections worldwide occur in Southeast Asia, Africa and the Western Pacific regions.4,5 The most common mode of transmission is through skin contact with contaminated soil. Strongyloidiasis can be asymptomatic or associated with non-specific complaints in more than half of cases, particularly in the chronic forms. In patients with subclinical infection who subsequently become immunosuppressed (corticosteroids, organ transplantation), larval reproduction can lead to disseminated infection. Chronic infection can become apparent in the form of eosinophilia and liver lesions.4,5 Liver lesions caused by S. stercoralis are the result of parasite migration in the liver parenchyma in the context of a disseminated disease caused by hyperinfection. However, they do not normally cause hypereosinophilia and the parasite is usually visible in the liver biopsy.5

Serology testing is the preferred diagnostic method, as it is more sensitive than stool analysis. Most serology tests measure the IgG response to an extract of larvae obtained from experimentally infected animals or related species of Strongyloides spp.4,5 The treatment of choice is ivermectin. In patients from areas endemic for Loiasis, a screening for loasis microfilaraemia (blood smear) should be performed prior to administration, as treatment with ivermectin in cases of a high parasite load may precipitate a potentially fatal Mazzotti reaction (fever, hypotension, encephalitis, etc).4

FundingThe authors declare that they received no funding to conduct this study.

Conflicts of interestJosé Luis del Pozo has participated in training or consulting activities funded by Pfizer, MSD, Gilead and Novartis.

The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.