Amyloidosis is characterized by the extracellular deposition of insoluble amyloid fibrils, which commonly results in systemic organs dysfunction. A single organ or tissue involved is uncommon, especially regarding the gastric localised amyloidosis. The lesion may manifest as erosions, ulcerations, nodular mucosa or polypoid protrusions. However, the specific treatment for localized amyloidosis has not been established. We present a case of gastric localized amyloidosis mimicking malignancy, in which endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was successfully done with the guidance of multiple endoscopic imaging techniques.

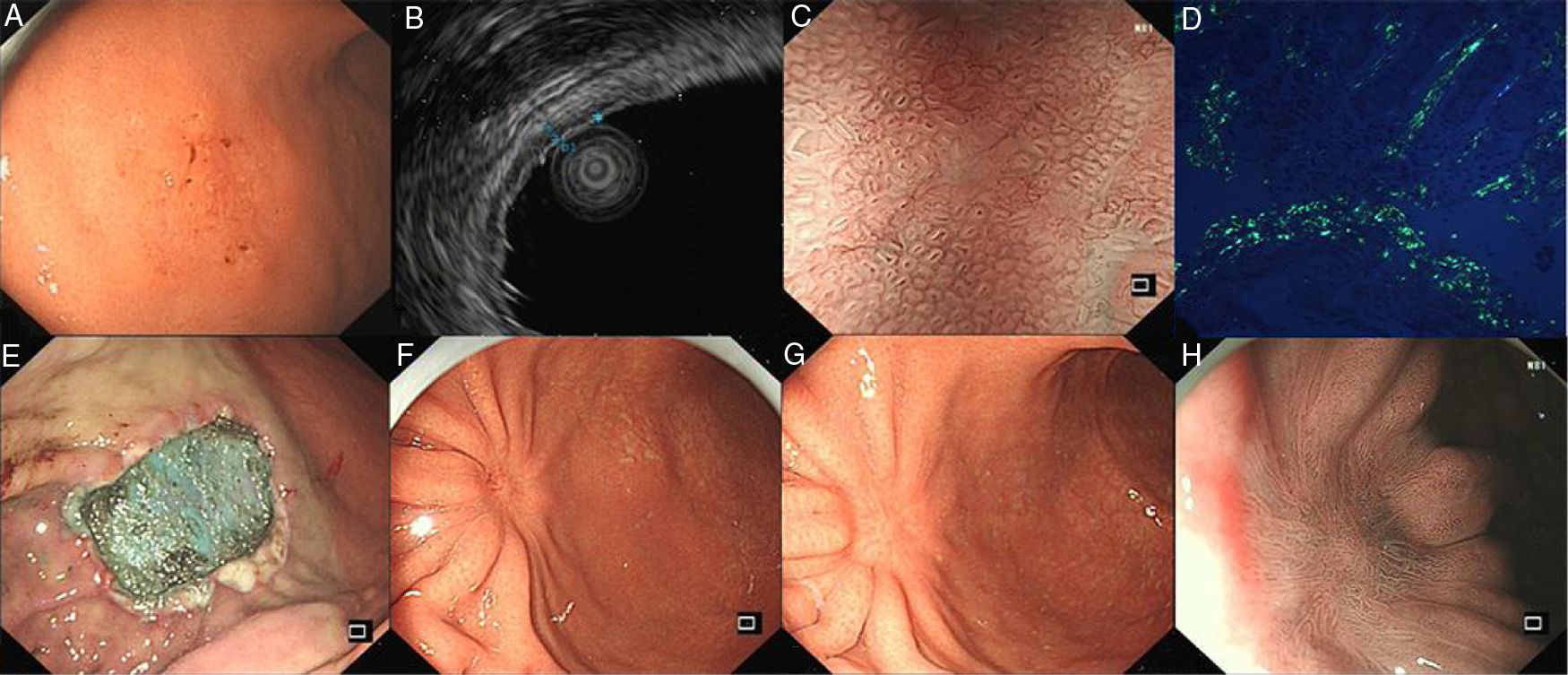

A 54-year-old man presented with occasional postprandial epigastric discomfort for several months. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed a 2.5cm×3.0cm flat depressed lesion in the gastric somatic and antral junction (Fig. 1A). The lesion resembled early gastric cancer with interrupted mucosal folds, spontaneous oozing on the surface and disappearance of partial border glandular structure. Endoscopy ultrasound evaluation (EUS) revealed the lesion originated from the mucosal layer. The first layer was thinned and the second layer was thickened with 1.4mm in the thickest part (Fig. 1B). Narrow-band imaging with magnified endoscopy (NBI+ME) showed the margin of the lesion was well-defined. The mucosal pit pattern was distorted, dilated and partially sparse, and the microvessels were obviously distorted, expanded or partially disappeared (Fig. 1C). However, histopathologic examination revealed an amorphous eosinophilic material deposition that extended from the lamina propria to the muscularis mucosae without malignant findings. The amyloid proteins were identified by Congo red staining and apple-green birefringence under polarized microscopy (Fig. 1D). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for κ and λ chain. Neither gastric fundus nor colorectal biopsy specimens showed amyloid deposition. The serum and urine immunoelectrophoresis were normal and there were no signs of amyloidosis in the kidney, heart and liver. A diagnosis of gastric localized amyloidosis with κ and λ light chain co-expression was made.

(A) EGD showed the flat depressed lesion in the stomach. (B) EUS revealed the first layer was thinned and the second layer was thickened. (C) NBI+ME showed the mucosal pit pattern and microvessels were obviously changed. (D) Apple green birefringence of amyloid deposition under polarized light. (E) Endoscopic submucosal dissection. (F,G,H) EGD revealed a scar formation and NBI+ME showed sparse glandular tube structure in 3 months and 1 years after surgery.

EGD, Esophagogastroduodenoscopy; EUS, Endoscopy ultrasound evaluation; NBI+ME, Narrow-band imaging with magnified endoscopy.

Subsequently, the ESD operation was performed with the guidance of NBI+ME and EUS (Fig. 1E). The postoperative specimens further confirmed amyloid deposition without malignant findings. There were no complications associated with the ESD. Three months and a year postoperatively, EGD was repeated (Fig. 1F–H). Mucosal biopsies from the centre and edge of the scar showed no amyloid deposition. The patient was curatively treated with symptom-free during the subsequent 12-month follow-up period.

Localized AL amyloidosis has a good prognosis, but 1–2% of patients exhibited systemic progression and 44% had progression at the primary site.1,2 A recent study ever revealed more than half of the patients with localized laryngeal amyloidosis developed localized recurrence, which required revision surgery in the first 4 years.3 22% of patients with GI localized amyloidosis may have localized progression,2 but it remains unclear whether localized progression affects disease prognosis. Although there are no standardized guidelines for the treatment of localized AL amyloidosis in gastrointestinal tract, the excision of the amyloid deposits and follow-up are the most common suggestions. GI bleeding, obstructive or abdominal pain may be a trigger for interventions in gastrointestinal deposits for symptomatic improvement.2 In a retrospective study, two symptomatic patients with GI localized amyloidosis were all relieved symptoms after the excision of lesions.4 Similarly, our patient was troubled by the occasional abdominal pain, which was gone after ESD.

Our case showed a type IIc lesion in the stomach which resembled early gastric cancer. Although the biopsy specimen showed the amyloid deposition, it could not rule out the possibility of biopsy bias. ESD has been widely accepted and used not only as a curative treatment for the early cancer in the gastrointestinal tracts but also as a diagnostic strategy for some confused cases.5 Gastric carcinoma was excluded finally in this case and the patient achieved curative treatment with the help of ESD. This case demonstrates that the thorough resection by ESD with guidance of NBI+ME and EUS is probably a safe and successful therapeutic choice for gastric localized amyloidosis mimicking malignancy in a symptomatic patient.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This work was financially supported by the grants from Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. LY16H030004].