Endoscopy is the gold standard for assessing disease severity in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), although it is an invasive procedure. Biological markers have been routinely used as a non-invasive means of determining disease activity. The aim of this study was to determine the correlation between common biological markers and endoscopic activity in IBD.

MethodsConsecutive patients with IBD were included. Serum concentrations of different biomarkers (C-reactive protein [CRP], orosomucoid [ORM], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], fibrinogen, platelets, leukocytes, neutrophils and hemoglobin [Hb]) were measured, and their accuracy in detecting endoscopic activity was determined.

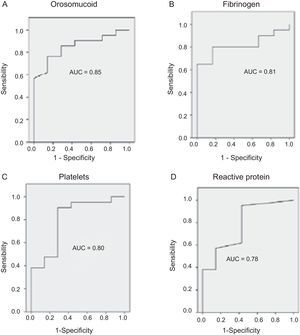

ResultsEighty patients were included (mean age 46 years, 53% Crohn's disease), 70% with endoscopic activity. Among Crohn's disease patients, 24% had mild endoscopic activity, 12% moderate activity and 39% severe activity. Among ulcerative colitis patients, 35% had an endoscopic Mayo score of 0–1 points, 30% 2 points and 35% 3 points. None of the biomarkers included had a good correlation with endoscopic activity (Area Under the ROC curve [AUC]<0.70) in ulcerative colitis. ORM, fibrinogen and platelets had the best accuracy to detect endoscopic activity in Crohn's disease (AUC: 0.80–0.085). A sub-analysis in postoperative Crohn's disease patients found no correlation between endoscopic recurrence and biomarkers (AUC<0.70).

ConclusionSerological biomarkers, including CRP, have low accuracy to detect endoscopic activity in ulcerative colitis and postoperative Crohn's disease. ORM, fibrinogen and platelets have the best accuracy to detect endoscopic activity in Crohn's disease.

La endoscopia es el criterio de referencia para evaluar la severidad en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII), aunque es un procedimiento invasivo. Se han utilizado rutinariamente marcadores biológicos como medios no invasivos para determinar la actividad de dicha enfermedad. El objetivo de este estudio fue el de determinar la correlación entre los marcadores biológicos comunes y la actividad endoscópica en la EII.

MétodosSe incluyó a pacientes consecutivos con EII. Se midieron las concentraciones séricas de los diferentes marcadores (proteína C reactiva, proteína orosomucoide, índice de sedimentación de eritrocitos, fibrinógeno, plaquetas, leucocitos, neutrófilos y hemoglobina) y se determinó su precisión en la detección de la actividad endoscópica.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 80 pacientes (edad media de 46 años, el 53% con enfermedad de Crohn), el 70% de ellos con actividad endoscópica. Entre los pacientes con enfermedad de Crohn, el 24% tenía una actividad endoscópica leve, el 12% moderada y el 39% una actividad severa. Entre los pacientes con colitis ulcerosa, el 35% tenía un índice de Mayo de 0–1 puntos, el 30% de 2 puntos y el 35% de 3 puntos. Ninguno de los biomarcadores incluidos reflejó una buena correlación con la actividad endoscópica (área bajo la curva ROC<0,70) en los casos de colitis ulcerosa. Los valores de proteína orosomucoide, fibrinógeno y plaquetas reflejaron la mejor fiabilidad para la detección de la actividad endoscópica en la enfermedad de Crohn (área bajo la curva ROC 0,80–0,085). Un subanálisis postoperatorio realizado a los pacientes con enfermedad de Crohn no reflejó relación alguna entre la recidiva endoscópica y los biomarcadores (área bajo la curva ROC<0,70).

ConclusiónLos biomarcadores séricos, incluyendo la proteína C reactiva, son poco fidedignos en los casos de colitis ulcerosa y enfermedad de Crohn postoperatoria. Los valores de proteína orosomucoide, fibrinógeno y plaquetas son más precisos para la detección de la actividad endoscópica en la enfermedad de Crohn.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic entities with a characteristic course including asymptomatic and active periods. Symptoms may vary from mild to severe abdominal pain or diarrhea, but these symptoms can be due to other processes: infectious diarrhea, irritable bowel syndrome, etc. Thus, the assessment of disease activity can be sometimes challenging if it is based only on clinical presentation.

Ileocolonoscopy is the gold standard to determine disease activity in IBD, although it is an invasive procedure.1 It has already been proven that there is a lack of concordance between clinical activity, on the one hand, and serological2 or endoscopic activity,3 on the other. Serological markers have been routinely used to determine disease activity in a non-invasive manner, but there is no proven evidence of their accuracy to assess endoscopic activity in IBD.

Due to the importance of mucosal healing, colonoscopy and cross-sectional imaging are proposed to guide the follow-up of IBD patients to adequately assess the presence of inflammation. However, colonoscopy is an invasive procedure, and both cross-sectional imaging and endoscopy are expensive and time consuming. For this reason, it would be useful to find indirect non-invasive markers that correlate with endoscopic activity. They might help to identify patients who should undergo an additional diagnostic (invasive or expensive) procedure and, accordingly, they could guide treatment decisions.4

Most of the serological biomarkers that have been previously evaluated are acute phase reactants, and therefore they can be elevated in the presence of multiple processes, including those with an extra-digestive origin. On the other hand, these biomarkers are inexpensive, easy to perform and non-invasive, what make them an attractive potential tool to assess disease activity in a daily practice setting. Nonetheless, several studies tried to evaluate the accuracy of serological biomarkers to determine endoscopic activity with confusing results, and only some studies have compared different biological markers in the same study population.

The aim of this study was to determine the correlation between common biological markers [C reactive protein (CRP), orosomucoid, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), fibrinogen, platelets, leukocytes, neutrophils and hemoglobin] and endoscopic activity in IBD patients.

MethodsStudy subjectsIn this retrospective study, the study sample comprised 80 patients followed-up at the IBD Unit from a single hospital, including CD and UC, who underwent an ileocolonoscopy between January 2010 and June 2011, and who had a serological determination within one month from the endoscopy. CD patients with ileal disease lacking an ileoscopy were evaluated with a magnetic resonance enterography (MRE). We defined UC and CD characteristics and location according to the Montreal classification.5 The local Ethics Committee approved our protocol. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Inclusion criteria(1) Diagnosis of IBD (established by standard clinical, radiographic, endoscopic, and histological criteria). (2) Patients with an endoscopic assessment of disease activity.

Exclusion criteria(1) Absence of serological or endoscopic evaluation. (2) CD patients with ileal disease without ileoscopy or MRE. (3) Patients with a serological determination separated more than one month from endoscopy.

Data collectionData collected included sex, age, location, extraintestinal manifestation, disease behavior (inflammatory, stenosing or fistulizing) and previous surgery.

Laboratory data included were hemoglobin, platelets, leukocytes, neutrophils, CRP, orosomucoid, ESR and fibrinogen.

The endoscopic activity was determined according to the endoscopist criteria in CD patients; in CD patients with previous intestinal surgical resection the Rutgeerts score was used, and for UC patients the endoscopic activity was defined according to the endoscopic Mayo score (UC-DAI). A single expert radiologist evaluated the presence or absence of radiological activity in MRE.

DefinitionsLaboratory abnormalities: All the laboratory parameters were defined as normal or increased according to our laboratory cut-off points: CRP>0.08mg/l; ESR>20mm/h; orosomucoid>125mg/dl; fibrinogen>500mg/dl; leukocytes>12,000/mm3; neutrophils>7500/mm3; platelets>400,000/mm3; hemoglobin<12g/dl for women and <13g/dl for men.

Endoscopic activity: The endoscopic activity in UC was classified as follows: no endoscopic activity (UC-DAI<2), moderate endoscopic activity (UC-DAI=2) and severe endoscopic activity (UC-DAI=3). We determined the endoscopic activity in CD according to the endoscopist criteria as mild, moderate and severe activity, based on the typical findings such as aphthous lesions, nodularity, erythema, ulcerations, stenosis and extension of activity. To define postoperative CD recurrence we selected a Rutgeerts score of i2 or more as indicative of active disease.

Radiological activity: MRE activity was determined by the radiologist criteria and classified just as active or inactive acute disease, based on the standard criteria: thickening of the bowel wall, contrast enhancement, mucosal ulceration or edema, hyperemia of the vasa recta (comb sign) and mesenteric adenopathy or edema. Activity on a MRE was considered equal to ileal endoscopic activity.

No changes in treatment were made between serological and endoscopic evaluations.

Statistical methodsThe mean±standard deviation was calculated for quantitative variables. Quantitative values were compared by use of Student's test. Qualitative values were compared by use of chi-squared test. P values were considered statistically significant if less than or equal to 0.05. The accuracy of each biomarker was assessed by the area under the ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve (AUC). The best cut-off value for each biomarker was identified; for it, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value were calculated. We considered the AUC as excellent, good, fair, poor or failed according to Kleinbaum's definition.6

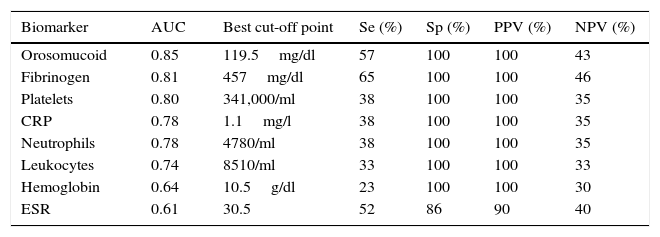

ResultsStudy populationA total of 80 patients diagnosed with IBD were included. The mean age was 46 years (range 18–82 years) and the mean time of evolution of the disease was 3 years. Fifty-five percent of all patients were male and 54% had CD. The characteristics of the patients included in the study are shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population (N=80).

| Age (in years) (SD) | 46 (15) |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Male/female | 44/36 | 55/45 |

| CD/UC | 43/37 | 54/46 |

| Endoscopic activity | 56 | 70 |

| Endoscopic disease severity | ||

| CD inactive/mild/moderate/severe | 11/10/5/17 | 25/23/12/40 |

| UC-DAI: 0–1 point/2 points/3 points | 13/11/13 | 35/30/35 |

| Postoperative CD recurrence (N=15) | 11 | 73 |

| Endoscopic activity in previously resected Crohn's disease patients | ||

| Rutgeerts i0–1/i2/i3/i4 | 4/2/0/9 | 27/13/0/60 |

SD: standard deviation; CD: Crohn's disease; UC: ulcerative colitis; UC-DAI: endoscopic Mayo score.

Twenty percent of patients with UC had a proctitis, 45% had left side colitis and 35% had a pancolitis. The most frequent location in CD was ileocolic (45%), and 30% had ileal disease. The CD behavior was inflammatory in 55% of patients, stenosing in 20% and fistulizing in 25%.

Seventy percent of patients had endoscopic activity. CD patients had mild endoscopic activity in 24% of cases, moderate disease in 12%, and 39% of patients had severe endoscopic activity. Fifteen patients with ileal CD were evaluated by MRE. In UC, patients had no activity, moderate and severe endoscopic activity in 35%, 30% and 35% of cases, respectively.

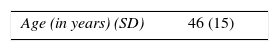

Serological biomarkersWhen comparing the mean values of the serological markers between patients with and without endoscopic activity, we did not find statistically significant differences in UC patients. By contrast, in CD patients without previous surgical resection, serological markers had higher mean values in the group with endoscopic activity, being these differences statistically significant for CRP, orosomucoid, fibrinogen, leukocytes, neutrophils and platelets (Table 2).

Comparison of the different mean values of serological biomarkers in Crohn's disease patients with and without activity at endoscopy.

| Biomarker | Patients without endoscopic activity | Patients with endoscopic activity | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| C reactive protein | 0.25±0.37mg/l | 4.2±7.6mg/l | <0.05 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 23±17mm/h | 30±22mm/h | n.s. |

| Orosomucoid | 75±22mg/dl | 143±76mg/dl | <0.01 |

| Fibrinogen | 364±61mg/dl | 501±159mg/dl | <0.01 |

| Leukocytes | 5649±1721/ml | 7836±3031/ml | <0.05 |

| Neutrophils | 3092±1139/ml | 5000±2158/ml | <0.05 |

| Platelets | 234±101 103/ml | 319±109×103/ml | <0.01 |

| Hemoglobin | 13±1.5g/dl | 11.9±2g/dl | <0.01 |

n.s.: not statistically significant.

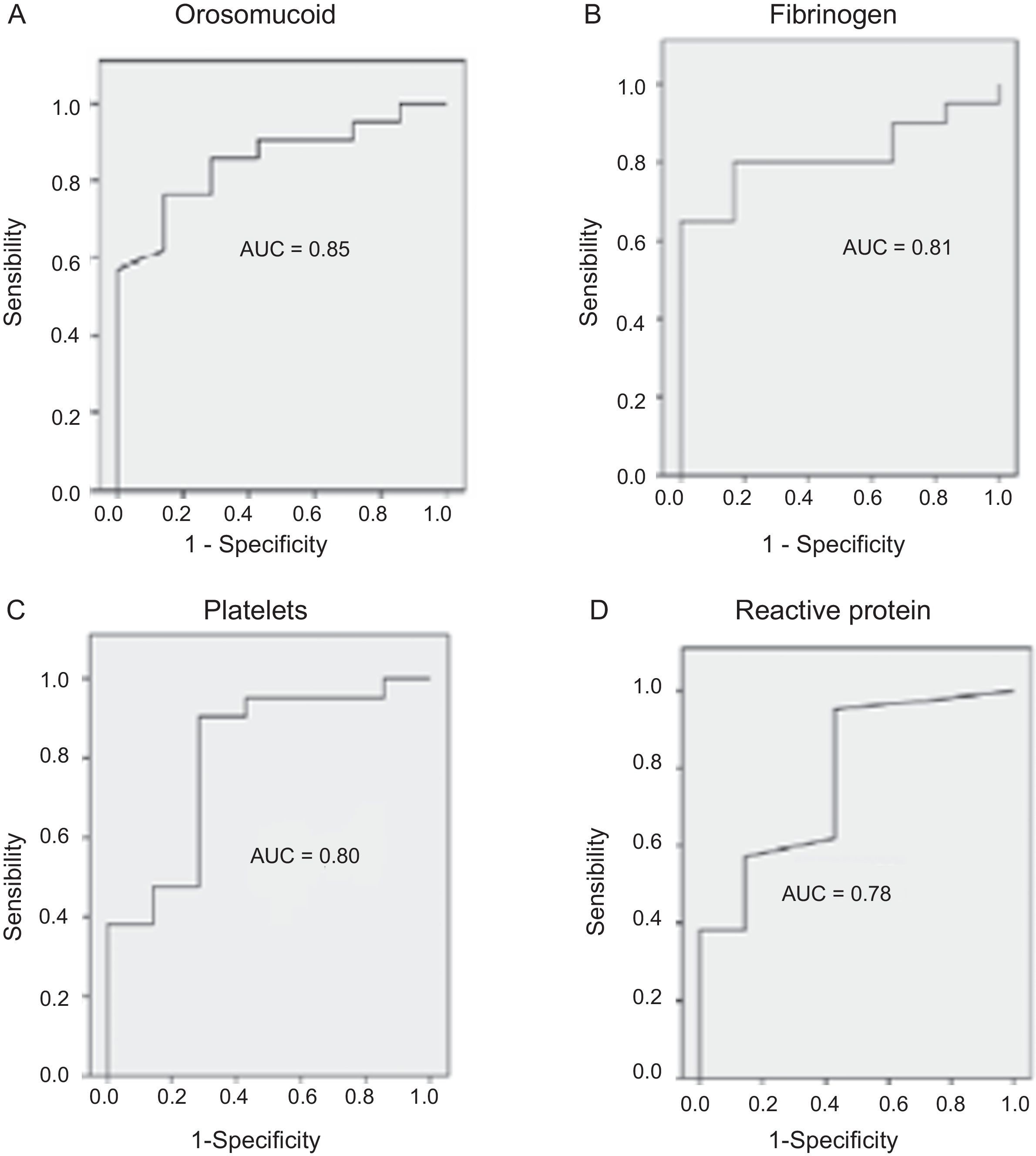

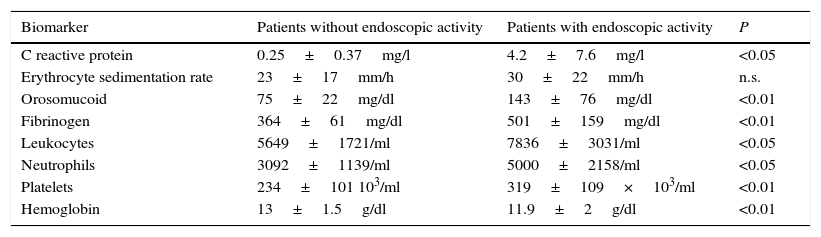

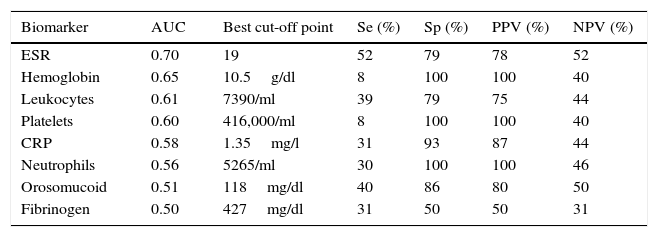

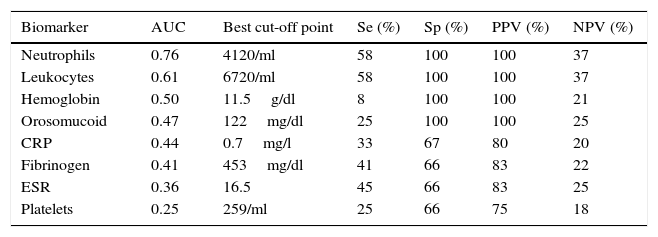

The serological biomarkers accuracy – assessed by the AUC, sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive values – for determining endoscopic activity in both CD and UC are shown in Tables 3 and 4. We performed a sub-analysis of the postoperative CD patients who had an ileoscopy (N=15; Table 5). None of the biomarkers included had a good correlation with endoscopic activity (AUC<0.70) in UC. Similar results were obtained for postsurgical recurrence in CD (AUC<0.7), with the exception of neutrophils (AUC=0.76). Orosomucoid, fibrinogen, platelets and CRP had the best accuracy for the detection of endoscopic activity in CD (AUC 0.80–0.85, Fig. 1).

Diagnostic accuracy of the serological biomarkers for detecting active disease at endoscopy in Crohn's disease without surgical resection.

| Biomarker | AUC | Best cut-off point | Se (%) | Sp (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orosomucoid | 0.85 | 119.5mg/dl | 57 | 100 | 100 | 43 |

| Fibrinogen | 0.81 | 457mg/dl | 65 | 100 | 100 | 46 |

| Platelets | 0.80 | 341,000/ml | 38 | 100 | 100 | 35 |

| CRP | 0.78 | 1.1mg/l | 38 | 100 | 100 | 35 |

| Neutrophils | 0.78 | 4780/ml | 38 | 100 | 100 | 35 |

| Leukocytes | 0.74 | 8510/ml | 33 | 100 | 100 | 33 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.64 | 10.5g/dl | 23 | 100 | 100 | 30 |

| ESR | 0.61 | 30.5 | 52 | 86 | 90 | 40 |

AUC: area under the ROC curve; Se: sensitivity; Sp: specificity; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value.

Diagnostic accuracy of the serological biomarkers for detecting active disease at endoscopy in ulcerative colitis.

| Biomarker | AUC | Best cut-off point | Se (%) | Sp (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESR | 0.70 | 19 | 52 | 79 | 78 | 52 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.65 | 10.5g/dl | 8 | 100 | 100 | 40 |

| Leukocytes | 0.61 | 7390/ml | 39 | 79 | 75 | 44 |

| Platelets | 0.60 | 416,000/ml | 8 | 100 | 100 | 40 |

| CRP | 0.58 | 1.35mg/l | 31 | 93 | 87 | 44 |

| Neutrophils | 0.56 | 5265/ml | 30 | 100 | 100 | 46 |

| Orosomucoid | 0.51 | 118mg/dl | 40 | 86 | 80 | 50 |

| Fibrinogen | 0.50 | 427mg/dl | 31 | 50 | 50 | 31 |

AUC: area under the ROC curve; Se: sensitivity; Sp: specificity; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value.

Diagnostic accuracy of the serological biomarkers for detecting active disease at endoscopy in postoperative Crohn's Disease.

| Biomarker | AUC | Best cut-off point | Se (%) | Sp (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophils | 0.76 | 4120/ml | 58 | 100 | 100 | 37 |

| Leukocytes | 0.61 | 6720/ml | 58 | 100 | 100 | 37 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.50 | 11.5g/dl | 8 | 100 | 100 | 21 |

| Orosomucoid | 0.47 | 122mg/dl | 25 | 100 | 100 | 25 |

| CRP | 0.44 | 0.7mg/l | 33 | 67 | 80 | 20 |

| Fibrinogen | 0.41 | 453mg/dl | 41 | 66 | 83 | 22 |

| ESR | 0.36 | 16.5 | 45 | 66 | 83 | 25 |

| Platelets | 0.25 | 259/ml | 25 | 66 | 75 | 18 |

AUC: area under the ROC curve; Se: sensitivity; Sp: specificity; PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value.

Our study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of serological biomarkers to determine the endoscopic activity in CD and UC patients. In general, we found a better correlation between endoscopic activity and serological biomarkers in CD than in UC. Orosomucoid, fibrinogen and platelets had the best AUC in CD patients: 0.85, 0.81 and 0.80, respectively. The diagnostic accuracy of the serological biomarkers in UC patients was bad, as none of them had an AUC>0.7. In postoperative CD patients, as expected, our results were also disappointing: all of them had an AUC<0.7, with the exception of neutrophils (AUC=0.76). However, neutrophils can be altered by treatment (thiopurines, corticosteroids), by concomitant infection or by concomitant hematological diseases, which limits its reliability.

Nowadays, the aim of IBD treatment is, increasingly, mucosal healing,7,8 as it is associated with better outcomes: lower hospitalization rate,7–9 lower bowel resection and colectomy rates,9–11 decreased use of corticoids,12 sustained clinical remission11,13 and decreased risk of colorectal cancer.14 Of note, there is no validated definition of mucosal healing to date.4 We defined mucosal healing based on previous studies,15,16 and we admitted the absence of vascular pattern and some erythema as no activity in UC (UC-DAI=0 and 1). In CD, mucosal healing was defined as a normal mucosa in patients without previous intestinal surgical resection. In those patients with intestinal surgery, a Rutgeerts score<i2 was accepted as mucosal healing based on the low rate of endoscopic recurrence associated to these alterations.17

Serological markers had in our study a great specificity to determine endoscopic activity in CD. Hence, in the presence of an elevated biomarker (mainly orosomucoid, fibrinogen, platelets and CRP) in a CD patient, further study with other biomarkers such as calprotectin, radiological evaluation or colonoscopy might be considered. Conversely, there was a lack of sensitivity of these biological markers, what should lead to incorporate other tools in order to better identify patients at risk of having active disease despite normal serological biomarkers.

CRP had in our study disappointing results. Actually, other biomarkers were superior to it, and it was just fairly accurate (AUC=0.78) to determine endoscopic activity in CD. It showed no diagnostic value in UC or postoperative CD recurrence. Previous data had confirmed that CRP was more useful in CD than in UC.18–20 The traditional explanation why CRP may be increased in CD and not in UC is that in CD the inflammation is transmural; in contrast, in UC the inflammation affects only the mucosa.21 However, controversial results have been reported concerning CRP and its relation to inflammation in IBD.22–25 Peyrin-Biroulet et al. recently found no correlation between symptoms, CRP and/or endoscopic activity in a cohort of the SONIC study.3 In UC patients, the study by Yoon et al. found that CRP had a modest sensitivity and specificity to detect endoscopic remission (53% and 71%, respectively).26 Schoepfer et al. concluded that CRP was superior to other serological biomarkers including platelets, hemoglobin and leukocytes, to assess endoscopic activity, but fecal biomarkers and even clinical activity correlated better than serological biomarkers with endoscopic activity in UC.27

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) of the gene regulating CRP production have been described and could explain why some patients with active disease do not increase CRP while others do even in the presence of mild inflammation.28,29 Besides, a high sensitive CRP has recently been developed and seems to have a good correlation with disease course; it may help in differentiating IBD from functional disorders and could guide the response to treatment, but it is not still routinely available.30–32

In CD patients with previous surgical resection, we found no correlation between endoscopic activity and serological markers, as expected. Even if our sample was small (N=15), our results were similar to those previously described in the literature.33,34 Thus, an ileocolonoscopy is still mandatory 6–12 months after surgery to rule out endoscopic recurrence and assess the risk of clinical recurrence in these patients.17,34,35

Orosomucoid had in our study high specificity and positive predictive value (both 100%), with a low sensitivity (57%), to identify endoscopic activity in CD. These good results were not confirmed in UC or postoperative CD. Early studies related orosomucoid to intestinal protein loss36 and, in the setting of active disease, the normalization of orosomucoid was associated with a less probable recurrence of the disease.37 However, due to its long half-live its use was abandoned.

ESR was the most accurate biomarker to assess the endoscopic activity in UC, although its AUC was only fair (0.70) and its sensitivity and specificity were low (52% and 79%, respectively), what shows that this marker has a very limited usefulness in IBD, as previously described.26,36,38

Our study confirmed the need for more sensitive and accurate biomarkers for IBD patients. Nonetheless, serological markers are of value when elevated in CD patients. Furthermore, they are cheap, widely available, easy to use and non invasive, what makes them good tools for routine use, maybe in combination with more sensitive diagnostic tests.

There is an increasing number of new biomarkers, including fecal biomarkers such as calprotectin or lactoferrin, that seem to have a promising diagnostic accuracy in both CD and UC, but their use is still to be defined.39 Calprotectin and lactoferrin are both specific markers of colic inflammation40; however, these markers are not IBD-specific, and they may be also increased in the presence of colorectal tumors, diverticular disease, infection or ischemia. In addition, their correlation with ileal disease is not clear yet. Calprotectin has been previously studied in comparison with traditional serum biomarkers. As an example, Sipponen et al. conducted a study where calprotectin had a better correlation with endoscopic activity in CD than clinical activity and CRP.41 A recent meta-analysis, evaluating the data from 13 studies concluded that calprotectin had an AUC of 0.93 in UC, and of 0.88 in CD, to determine active IBD. Hence, calprotectin might be a reliable marker of activity in IBD, maybe more accurate in UC that in CD.42 Finally, some authors have also proposed that calprotectin may predict post-operative endoscopic recurrence in CD patients, in a study where CRP, once again, was useless in this kind of patients.43

Our study included patients with an endoscopic evaluation, and it compared different biomarkers in the same patients. However, this was a single-center study and our data need further confirmation. Another limitation of our study is that we did not use a standardized method to evaluate the endoscopic activity in CD, but the endoscopic scores available as the Crohn's Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity (CDEIS) or even the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn's Disease (SESCD) are relatively difficult to use in clinical practice.8 Nonetheless, the physicians based their assessment in the same endoscopic criteria included in aforementioned scores. The subgroup of patients with postoperative CD recurrence was small, and no definitive conclusions can be inferred from this study, but our results suggest that serological biomarkers are useless in these patients. MRE was performed in all patients with known ileal disease who had no endoscopic evaluation of the ileon. However, we could have missed proximal activity in areas non accessible to endoscopy or in other patients in whom we did not perform a radiological evaluation of the proximal bowel. Finally, this was a transversal study, so we cannot estimate if biomarkers can predict the disease course or the response to treatment, but these objectives were not a part of the present study.

In summary, the correlation between serological biomarkers and endoscopic activity in UC and postoperative CD is remarkably low. Orosomucoid, fibrinogen and platelets have the best accuracy for the detection of endoscopic activity in CD, with high specificity and high positive predictive value. CRP is not the most accurate serological biomarker in IBD.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

None.