Colonic pseudopolyps or post-inflammatory polyps that arise in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are projecting non-neoplastic inflammatory lesions. They differ histologically from adenomatous or hyperplastic polyps. Although they are associated with extensive forms of the disease, they are not considered a poor prognostic factor.1

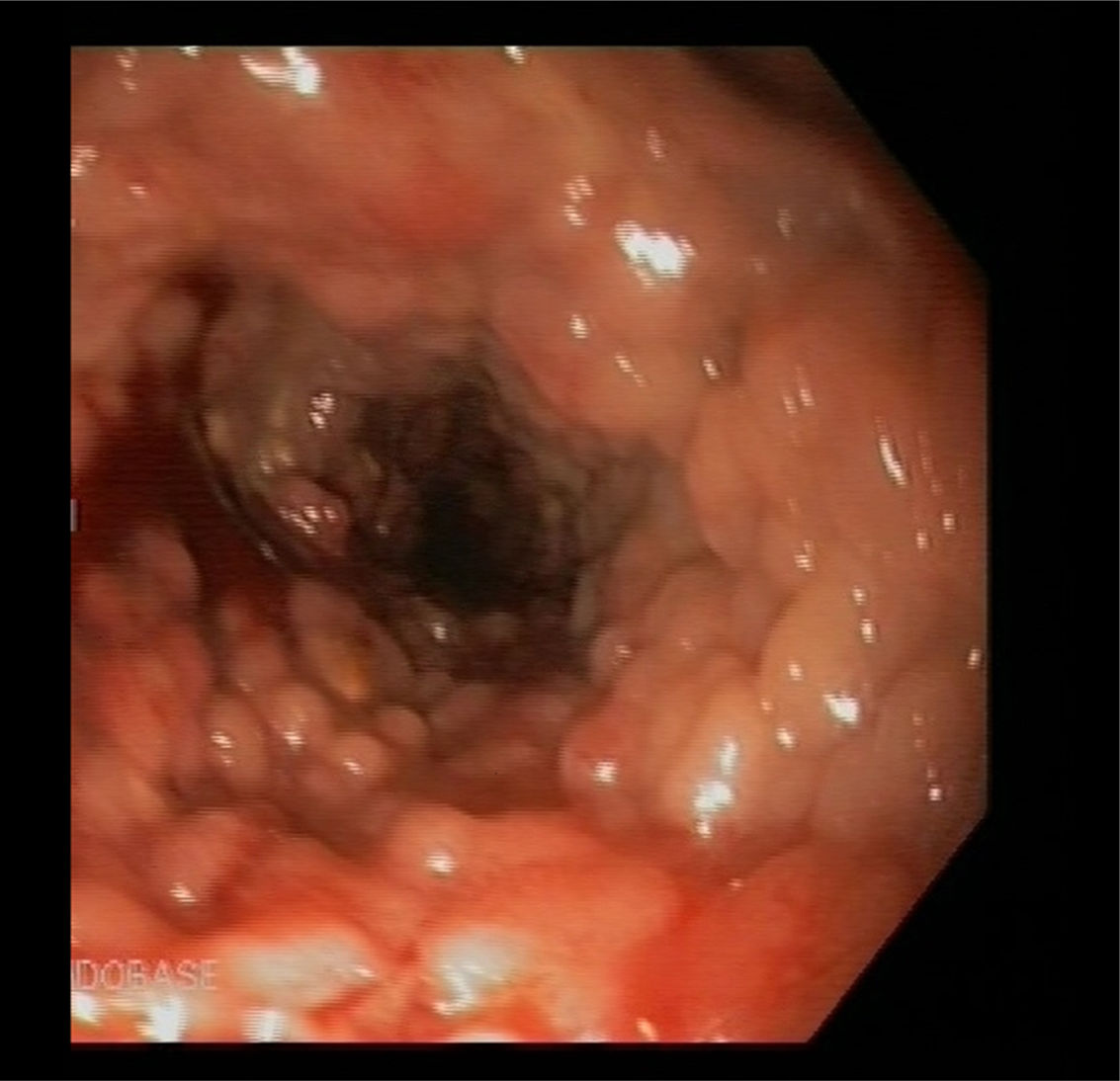

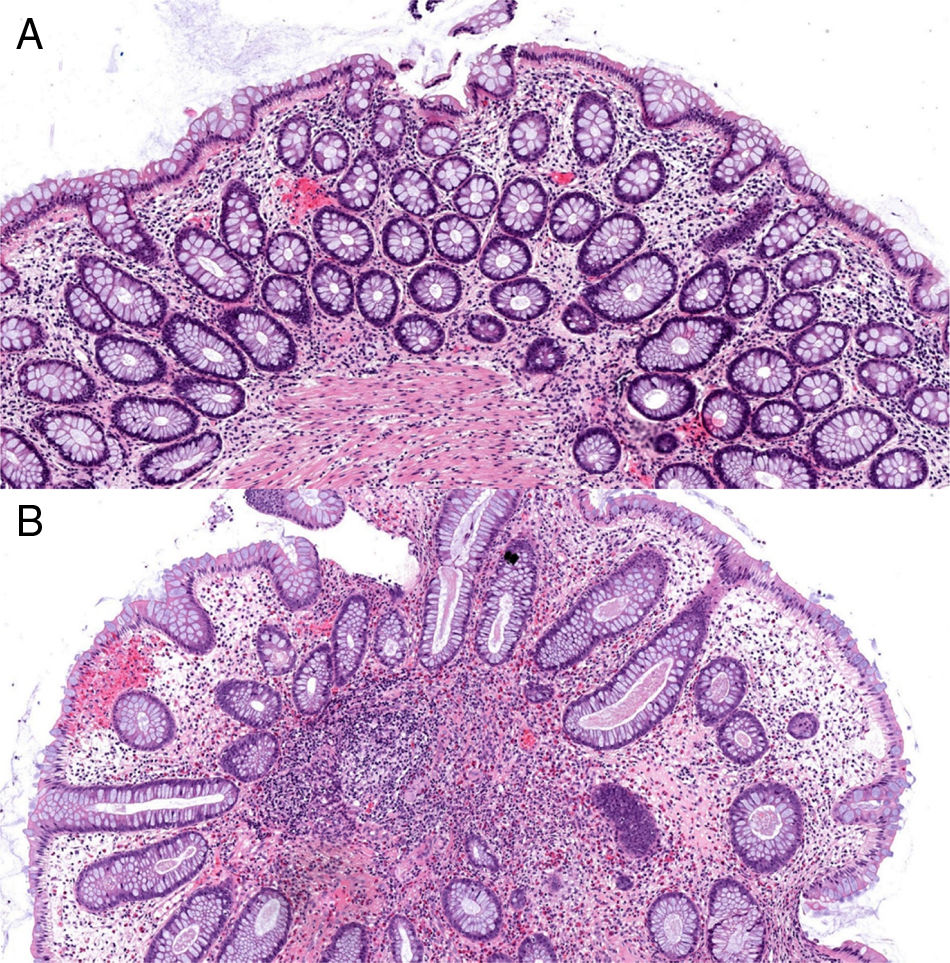

We present the case of a 37-year-old male patient who initially attended following a two-month history of four loose bowel movements a day, together with fever and weight loss. The blood tests revealed iron deficiency anaemia. The colonoscopy showed multiple 5–10mm sessile polyps covering the entire wall, starting 20cm from the anal margin up to the hepatic flexure (Fig. 1). They were histologically defined as inflammatory pseudopolyps with altered glandular architecture and increased inflammatory infiltrate, similar to pseudopolyps prevalent in ulcerative colitis (Fig. 2). The full-body MRI revealed dilatation and rigidity of the entire colon to the rectum, as well as deformed folds. With an initial diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease of unknown cause, treatment was started with mesalazine 4g/day.

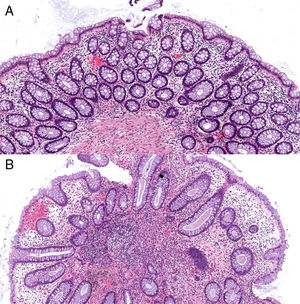

Haematoxylin and eosin stain (100× magnification). (A) Mucosa of the large intestine with preserved architecture, crypts covered by goblet cells and negligible nonspecific inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate in the layer itself. (B) Polypoid formation with distorted colonic epithelium showing some slightly dilated crypts and some branching crypts, surrounded by an inflammatory layer.

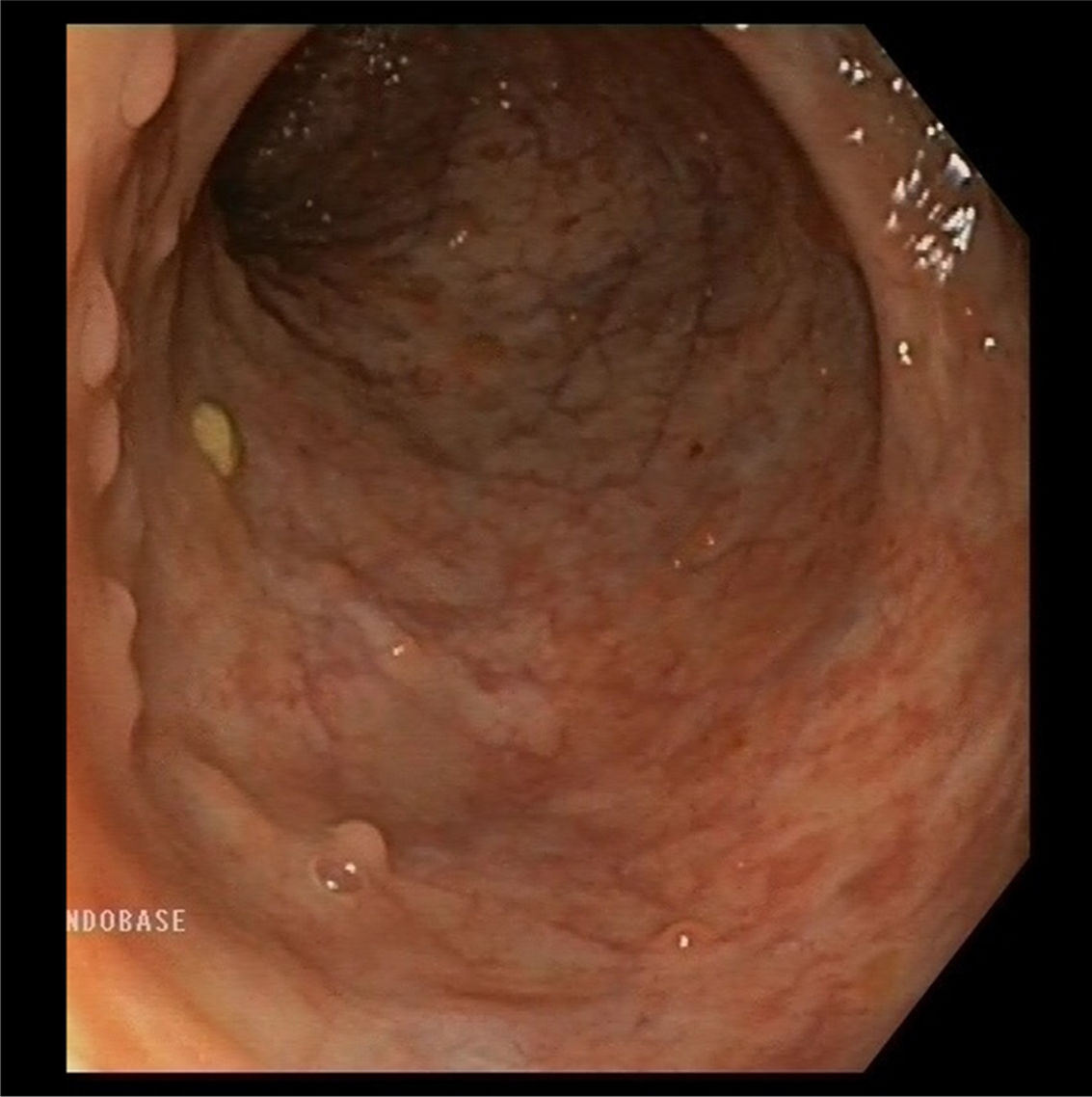

After seven months of clinical improvement, the patient was admitted for a moderate-severe relapse, presenting with severe endoscopic activity in the transverse colon, mucosal bridges and deep ulcers. Treatment was started with infliximab 10mg/kg and azathioprine 2.5mg/kg. After 18 months, the patient is in clinical remission with mucosal and histological recovery (Fig. 3).

Pseudopolyps are the most common local complication of ulcerative colitis.1 They are caused by mucosal repair after chronic inflammation. They can manifest in both the active and inactive phases of the disease and may be widespread or localised. In our patient they were already present at the time of diagnosis, probably due to prior subclinical mucosal activity.

They manifest in 10–62% of all ulcerative colitis cases and have also been reported in infectious colitis, diverticulosis, in the proximity of anastomosis and occasionally in ischaemic conditions.1,2 Their size generally ranges from a few millimetres to 1cm, but they can also form a mass (giant pseudopolyposis) that simulates a villous adenoma or adenocarcinoma,3,4 or even cause intestinal occlusion.5

Pseudopolyposis per se does not require specific medical treatment. However, in cases where symptoms such as bleeding ulcers or obstruction arise, endoscopic treatment or surgery may be necessary. Controlling inflammatory activity may be associated with a reduction in the size of the pseudopolyps.6 Pseudopolyposis is not considered to be a precancerous condition despite the fact that it is associated with a higher risk of colorectal cancer, probably caused by greater prior inflammation of the adjacent mucosa.7,8 Dysplasia in giant pseudopolyps have only been reported anecdotally.9

In our case, the initial endoscopic findings were of note, with significant and persistent polypoid involvement in an isolated segment of the colon without showing the adjacent mucosa, suggestive of other diseases, such as juvenile polyposis syndrome, hamartomatous polyps or familial adenomatous polyposis. These entities are clinically significant and each requires different treatment. As such, it is important to take these lesions into account when establishing a differential diagnosis in the event of similar endoscopic findings. Post-inflammatory polyps are a malignancy risk marker in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Should they manifest, the surrounding mucosa should be examined carefully as they can sometimes be difficult to see due to their size or position. In addition, a dysplasia follow-up endoscopic examination should be conducted in 2–3 years. Chromoendoscopy would be the technique of choice whenever it is available.10

Please cite this article as: Monteserín L, Jiménez M, Molina G, Reyes N, Hernando M, Sierra M, et al. Pseudopoliposis colónica en enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:375–376.