To assess the incidence and factors associated with constipation in adult critical care patients.

DesignProspective cohort study.

Settingintensive care unit (ICU) of a high-complexity hospital from November 2015 to October 2016.

Patientsadults who were hospitalized for at least 72h in the ICU were followed from their admission to the ICU until their departure.

InterventionsNone.

Measurements and main resultsIn the 157 patients followed up, the incidence of constipation was 75.8%. The univariate analysis showed that constipated patients were younger, used more sedation and showed more respiratory and postoperative causes for hospitalization, while non-constipated patients were hospitalized more for gastrointestinal reasons. The use of vasoactive substances, mechanical ventilation and haemodialysis was similar between the constipated and non-constipated patients. Multivariate analysis, days of use of docusate+bisacodyl (HR: .79; 95% CI: .65–.96) of omeprazole or ranitidine (HR: .80; 95%CI: .73–.88) and lactulose (HR: .87; 95%CI: .76–.99) were independent protection factors for constipation.

ConclusionConstipation has a high incidence among adult critical care patients. Days of drug use acting on the digestive tract (lactulose, docusate+bisacodyl and omeprazole and/or ranitidine) are able to prevent this outcome.

Valorar la incidencia y factores de riesgo asociados al estreñimiento en pacientes adultos, en estado crítico.

DiseñoEstudio prospectivo de cohortes.

ÁmbitoUnidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI) de un hospital de alta complejidad de noviembre de 2015 a octubre de 2016.

SujetosSe realizó un seguimiento a los adultos que fueron hospitalizados durante al menos 72h en la UCI, desde su ingreso en dicha unidad hasta su salida.

IntervencionesNinguna.

Mediciones y resultados principalesEn los 157 pacientes seguidos, la incidencia de estreñimiento fue del 75,8%. El análisis univariado mostró que los pacientes con estreñimiento eran más jóvenes, habían usado más sedación y habían tenido más problemas respiratorios y posoperatorios como causas de hospitalización. Los pacientes sin estreñimiento habían sido hospitalizados más veces debido a motivos gastrointestinales. El uso de fármacos vasoactivos, la ventilación mecánica y la hemodiálisis fue similar entre los pacientes con estreñimiento y aquellos sin estreñimiento. El análisis multivariado, los días de administración de docusato+bisacodilo (HR0,79; IC95%: 0,65–0,96), de omeprazol o ranitidina (HR: 0,80; IC95%: 0,73–0,88) y de lactulosa (HR: 0,87; IC95%: 0,76–0,99) fueron factores independientes de protección para el estreñimiento.

ConclusiónEl estreñimiento es muy incidente en los adultos críticos. Los días de administración de fármacos que actúan sobre el tracto digestivo (Lactulosa, docusato+bisacodil y omeprazol y/o ranitidina) son capaces de prevenir este desenlace.

Studies suggest that the patient's clinical status and his or her demand for treatments are considered risk factors for constipation, prospective studies that determine the independent contribution of each one and other variables for the occurrence of constipation are rare.

The incidence of constipation in adult critical care patients is high. The number of days using the gastrointestinal tract, adjusted for the number of days until evacuation, are independent of protective factors for constipation.

Implications of the study?Understanding these characteristics will allow advancing in the implementation of guideline protocols managed by nursing to prevent constipation, minimizing the occurrence of outcomes associated with it. The adoption of other data analysis strategies, or even an increase in the number of observations, may contribute to the identification of risk variables for constipation.

Although some evidence shows that constipation is a risk factor for worse clinical outcomes (mechanical ventilation time,1,2 stay in the intensive care unit (ICU),2–4 infection and mortality5), few studies have been concerned with establishing its incidence and its determinants in critical care patients. There is no consensus concept that characterizes constipation; more sensitive criteria define higher incidences, while the more specific criteria, in minors, lead to a high variability in the constipation incidence (9%6 to 96%7).

Among the few studies that evaluated factors associated to constipation in critically ill adults, Sharma et al. adopted univariate analyses in a small and intentional sample and found that patients of fasting (p<0.01), bed rest (p<0.001), used drugs such as opioids, analgesics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, sedatives, iron and calcium supplements (p<0.001), and subjected to ventilation (p<0.05), showed fewer evacuations.8 Bishop9 demonstrated that lactulose use (p=0.009) and ondansetron (p=0.02) were independently associated with the presence of daily evacuation, while morphine use (p=0.025) was associated with absence of evacuation. In a study evaluating independent risk factors for what they called “gastrointestinal transit disorder” (defined as absence of evacuation for three or more days after initiation of the enteral nutrition and after initiation of constipation treatment, associated with at least one of the following events1: evidence of adynamic ileus,2 food intolerance,3 abdominal distension or4 need for gastric decompression), the use of prophylaxis for constipation (senna extract, docusate sodium, metoclopramide, domperidone, or erythromycin) (OR: 3.5; CI95%: 1.4–8.8) and opioids (OR: 1.05; CI95%: 1.02–1.07)10 were associated with the disorder under study. The treatment attributed to the critical care patient is related to constipation in other studies. In patients with severe trauma, although without adjustment for confounding factors, constipated patients remained longer on mechanical ventilation (MV) (p<0.001), more days using morphine (p<0.001), more days under sedation (p<0.001) and more days using neuromuscular blockade (p<0.001).11 In patients with prolonged MV, the PaO2/FiO2 ratio <150mmHg (OR=1.4, CI95%: 1.1–1.6), the systolic blood pressure between 70 and 89mm Hg (OR=1.5, CI95%: 1.2–1.8), and systolic blood pressure <69mmHg (OR=1.3; CI95%: 1.01–1.6) during the first five days of MV were identified as independent risk factors for delayed evacuation.5 Recently, Prat et al. showed that constipated patients also used more MV (p<0.001), sedation (p<0.0001), vasopressors (p=0.02), enteral nutrition (p<0.001) and neuromuscular blockade (p=0.0001).12 After analyzing the first six days of hospitalization, Van der Spoel et al. showed that patients who had precocious evacuation used less noradrenaline (1.0μg/kg/min vs 3.7μg/kg/min, p<0.002), dopamine (2.3g/kg/min vs 7.7μg/kg/min; p<0.002) and morphine (68% vs 83% of the days; p=0.008).2

Montejo et al.13 and Nguyen et al.10 identified that patients with constipation or with the so-called “impaired gut transit” reached fewer nutritional goals (p<0.001 in both studies). Bolus infusion was also associated with a lower incidence of constipation.14 However, it should be pointed out that the study that showed this result used a small sample (n=30) and excluded patients who received sedatives or vasoactive substances and septic shocks, characterizing a profile of minor severity that does not seem to correspond generally to the clinical reality of patients in ICUs.

The nurse who works in intensive care must be able to integrate the technology to care, mastering the scientific principles that underlie its use and at the same time supplying the therapeutic needs of the patients.15 Among the many care expended on critical patients, those related to eliminations are fully attributed to nursing. Diarrhea is usually more signaled by the nursing team as it adds workload. Already the occurrence of constipation seems neglected, little prioritized and rarely discussed among care teams, taking actions only in extreme situations. Care and treatments that use hard technologies seem to receive more attention from teams.

Although these findings suggest that the patient's clinical status and his or her demand for treatments, especially in the first days of ICU stay, are considered risk factors for constipation, prospective studies that determine the independent contribution of each one and other variables for the occurrence of constipation are rare. Understanding these characteristics will allow advancing in the implementation of guideline protocols to prevent this condition, minimizing the occurrence of outcomes associated with it.

ObjectiveTo assess the incidence and factors associated with constipation in adult critical care patients.

MethodDesignProspective cohort study

EnvironmentThe study was developed at critical care center, consisting of three integrated ICUs, totaling 40 clinical and surgical beds, but not trauma, of a university hospital of high complexity. The study was conducted from November 2015 to October 2016.

SubjectsIt was included adults (age >18 years) who were hospitalized for at least 72h in the ICU, except for those who showed diarrhea or constipation at ICU admission, postoperative of surgeries requiring preoperative bowel preparation with enemas, with ostomies.

Study protocolNurses previously trained to obtain data through research forms conducted the study. It was established that 10 patients would be followed simultaneously; thus, patients were included until reaching the established number and were followed daily until their departure from the ICU. At each exit from the study, a new patient (the next eligible ICU admission) was included.

Data collectionThe data were obtained through direct observation and in the patient's medical records. For the daily evaluation, an instrument developed by the researchers was adopted, which included demographic, clinical data (reason for ICU admission, previous diseases, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II, sepsis-related organ failure assessment (SOFA), Glasgow, Richmond agitation and sedation scale for patients under sedation, among others), treatments in use (medication, MV, renal replacement therapy, nutritional therapy/fasting), mobility (evaluated through the “mobility” subscale of Braden scale), Nursing Activities Score, days of ICU stay and mortality, incidence of other gastrointestinal disturbances, number of bowel movements per day.

DefinitionAs well as in previous studies,1,16 constipation was defined as the absence of evacuation for three consecutive days.

Analysis of the dataExpecting to find incidence equal to or greater than that obtained in the study of Nassar16 (70%) and following the recommendation of Fletcher17 of including 10 outcomes for each variable in the multivariate model, predicting the inclusion from 8 to 10 variables in the model, the sample was estimated in 143 patients.

Data were entered and analyzed in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 (IBM, Chicago, Illinois, USA); parametric and non-parametric methods were adopted, according to the characteristics and distribution of variables, besides the assumptions from each test. The “enter” function for the multiple Cox regression was adopted and variables whose p-value was ≤0.25 were included in the univariate Cox analysis. Days until the first evacuation constituted the time adjustment variable and the model adjustment was evaluated through the Omnibus test. In the analysis, the data were censored in 10 days of observation.

Ethical responsibilitiesHis study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (No. 15-0376).

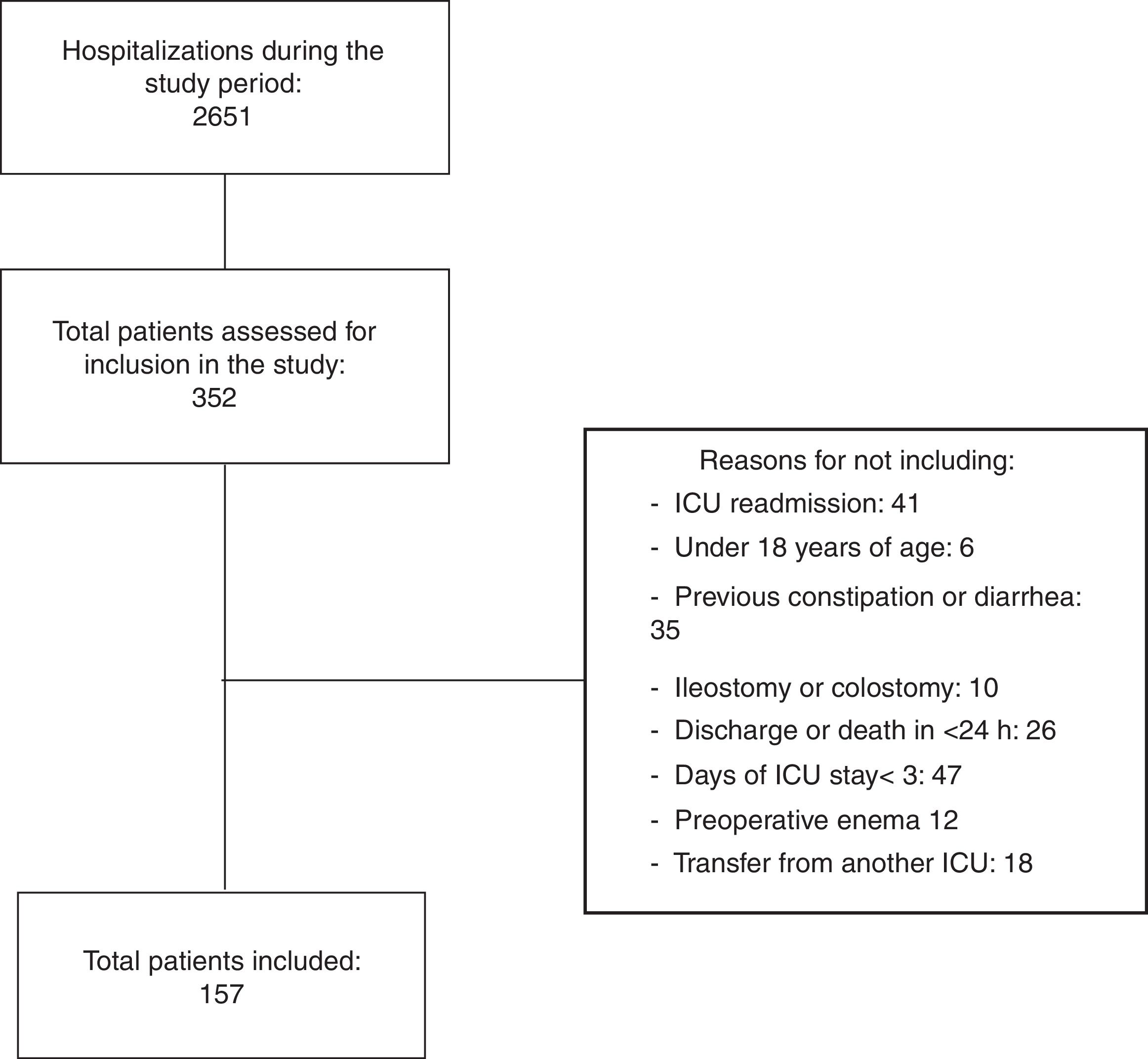

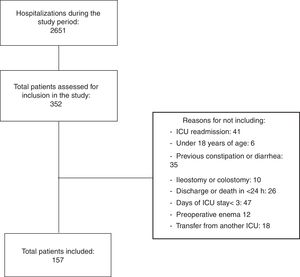

ResultsThe intentionality of simultaneous follow-up of up to 10 patients was followed. Thus, from the 2651 patients admitted to the ICU throughout the study, 352 were assessed in relation to eligibility criteria. From these, 157 patients showed the total criteria and were effectively included (Fig. 1).

The patients showed different reasons for ICU admission, and about 30% were surgical; despite the low average age (58.3±15.2), many (98.7%) showed previous diseases. More than half showed neurological abnormalities (Glasgow ≤9 or RASS ≤−2) and predictive complication severity indices (APACHE 21.5±8.4 and SOFA 6.5±3.8), requiring ventilatory support (79%), dialysis (25%), hemodynamic (65.6%), sedation (79%), analgesia (up to 63.1%), medications for prophylaxis of gastrointestinal bleeding (86.6%) throughout ICU stay. Moreover, most of them used drugs with action on the gastrointestinal tract. Most of the patients showed mobility problems (88.5%) and remained many hours/day (7.0; IQR: ±3) fasting. The sample did not count on patients using parenteral nutrition and pregnant women, although they were not excluded by the eligibility criteria.

From the total number of patients (n=157), 119 (75.8%) showed one or more constipation episodes in the follow-up period, distributed in the following moments: (a) 58 did not evacuate during all ICU stay, (b) 51 patients did not evacuate until the third day of ICU stay, (c) nine patients evacuated during the first days of hospitalization, but showed constipation on subsequent days and (d) one patient evacuated after 10 days of hospitalization (censored data for this analysis).

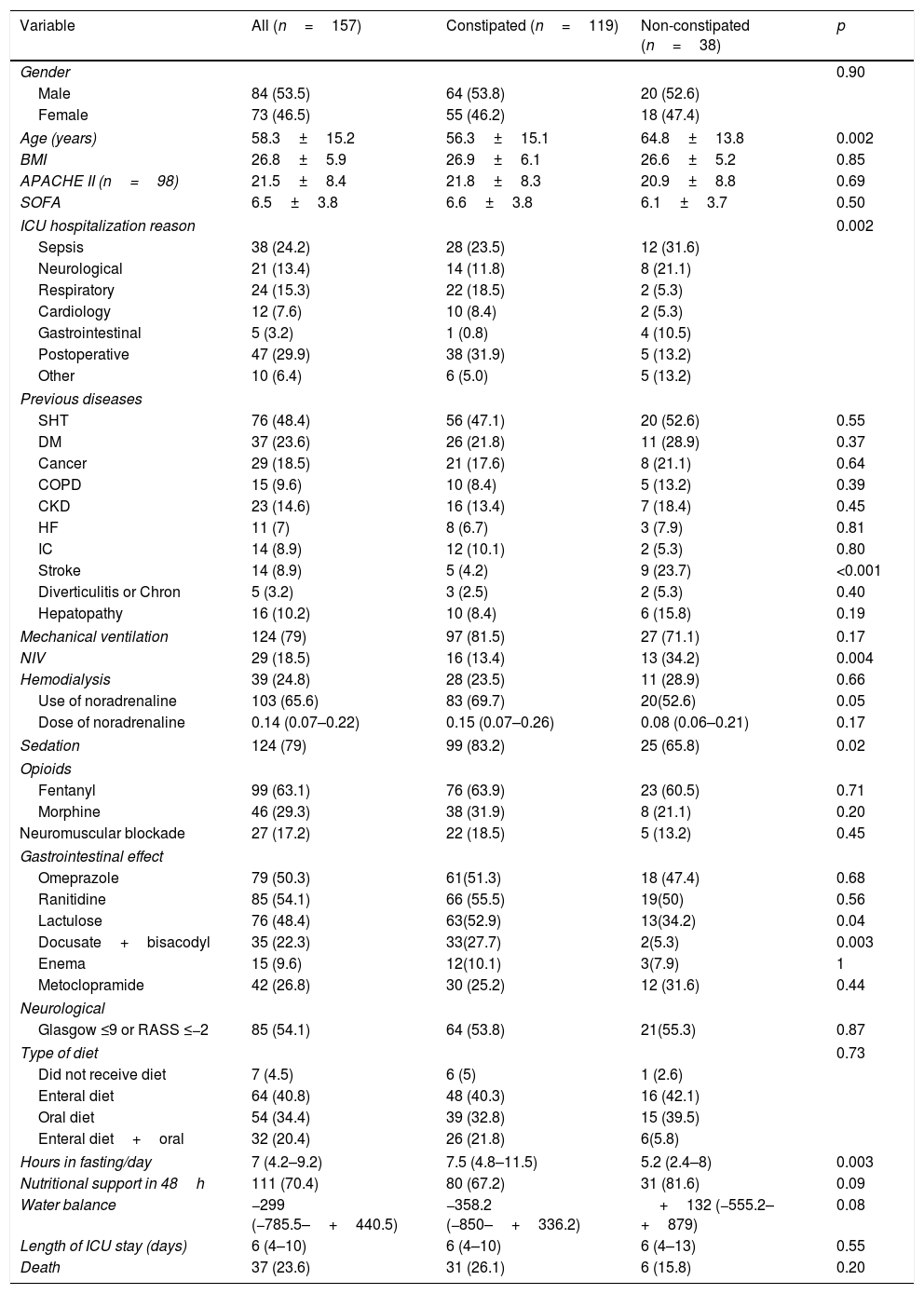

The univariate analysis showed that constipated and non-constipated patients resembled their different characteristics and interventions adopted in the ICU, with exception of constipated patients that were younger (p=0.002), hospitalized more due to postoperative period and less for gastrointestinal reasons (p=0.002), besides showing less cerebrovascular accident prior to hospitalization (p<0.001). On the other hand, the use of noninvasive ventilation (NIV) (p=0.004), sedation (p=0.02), and noradrenaline (p=0.05) was more frequent in the constipated patients group (Table 1).

Characteristics of the total sample of patients and treatments attributed to patients with and without constipation.

| Variable | All (n=157) | Constipated (n=119) | Non-constipated (n=38) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.90 | |||

| Male | 84 (53.5) | 64 (53.8) | 20 (52.6) | |

| Female | 73 (46.5) | 55 (46.2) | 18 (47.4) | |

| Age (years) | 58.3±15.2 | 56.3±15.1 | 64.8±13.8 | 0.002 |

| BMI | 26.8±5.9 | 26.9±6.1 | 26.6±5.2 | 0.85 |

| APACHE II (n=98) | 21.5±8.4 | 21.8±8.3 | 20.9±8.8 | 0.69 |

| SOFA | 6.5±3.8 | 6.6±3.8 | 6.1±3.7 | 0.50 |

| ICU hospitalization reason | 0.002 | |||

| Sepsis | 38 (24.2) | 28 (23.5) | 12 (31.6) | |

| Neurological | 21 (13.4) | 14 (11.8) | 8 (21.1) | |

| Respiratory | 24 (15.3) | 22 (18.5) | 2 (5.3) | |

| Cardiology | 12 (7.6) | 10 (8.4) | 2 (5.3) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 5 (3.2) | 1 (0.8) | 4 (10.5) | |

| Postoperative | 47 (29.9) | 38 (31.9) | 5 (13.2) | |

| Other | 10 (6.4) | 6 (5.0) | 5 (13.2) | |

| Previous diseases | ||||

| SHT | 76 (48.4) | 56 (47.1) | 20 (52.6) | 0.55 |

| DM | 37 (23.6) | 26 (21.8) | 11 (28.9) | 0.37 |

| Cancer | 29 (18.5) | 21 (17.6) | 8 (21.1) | 0.64 |

| COPD | 15 (9.6) | 10 (8.4) | 5 (13.2) | 0.39 |

| CKD | 23 (14.6) | 16 (13.4) | 7 (18.4) | 0.45 |

| HF | 11 (7) | 8 (6.7) | 3 (7.9) | 0.81 |

| IC | 14 (8.9) | 12 (10.1) | 2 (5.3) | 0.80 |

| Stroke | 14 (8.9) | 5 (4.2) | 9 (23.7) | <0.001 |

| Diverticulitis or Chron | 5 (3.2) | 3 (2.5) | 2 (5.3) | 0.40 |

| Hepatopathy | 16 (10.2) | 10 (8.4) | 6 (15.8) | 0.19 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 124 (79) | 97 (81.5) | 27 (71.1) | 0.17 |

| NIV | 29 (18.5) | 16 (13.4) | 13 (34.2) | 0.004 |

| Hemodialysis | 39 (24.8) | 28 (23.5) | 11 (28.9) | 0.66 |

| Use of noradrenaline | 103 (65.6) | 83 (69.7) | 20(52.6) | 0.05 |

| Dose of noradrenaline | 0.14 (0.07–0.22) | 0.15 (0.07–0.26) | 0.08 (0.06–0.21) | 0.17 |

| Sedation | 124 (79) | 99 (83.2) | 25 (65.8) | 0.02 |

| Opioids | ||||

| Fentanyl | 99 (63.1) | 76 (63.9) | 23 (60.5) | 0.71 |

| Morphine | 46 (29.3) | 38 (31.9) | 8 (21.1) | 0.20 |

| Neuromuscular blockade | 27 (17.2) | 22 (18.5) | 5 (13.2) | 0.45 |

| Gastrointestinal effect | ||||

| Omeprazole | 79 (50.3) | 61(51.3) | 18 (47.4) | 0.68 |

| Ranitidine | 85 (54.1) | 66 (55.5) | 19(50) | 0.56 |

| Lactulose | 76 (48.4) | 63(52.9) | 13(34.2) | 0.04 |

| Docusate+bisacodyl | 35 (22.3) | 33(27.7) | 2(5.3) | 0.003 |

| Enema | 15 (9.6) | 12(10.1) | 3(7.9) | 1 |

| Metoclopramide | 42 (26.8) | 30 (25.2) | 12 (31.6) | 0.44 |

| Neurological | ||||

| Glasgow ≤9 or RASS ≤−2 | 85 (54.1) | 64 (53.8) | 21(55.3) | 0.87 |

| Type of diet | 0.73 | |||

| Did not receive diet | 7 (4.5) | 6 (5) | 1 (2.6) | |

| Enteral diet | 64 (40.8) | 48 (40.3) | 16 (42.1) | |

| Oral diet | 54 (34.4) | 39 (32.8) | 15 (39.5) | |

| Enteral diet+oral | 32 (20.4) | 26 (21.8) | 6(5.8) | |

| Hours in fasting/day | 7 (4.2–9.2) | 7.5 (4.8–11.5) | 5.2 (2.4–8) | 0.003 |

| Nutritional support in 48h | 111 (70.4) | 80 (67.2) | 31 (81.6) | 0.09 |

| Water balance | −299 (−785.5–+440.5) | −358.2 (−850–+336.2) | +132 (−555.2–+879) | 0.08 |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 6 (4–10) | 6 (4–10) | 6 (4–13) | 0.55 |

| Death | 37 (23.6) | 31 (26.1) | 6 (15.8) | 0.20 |

Caption: BMI – body mass index; APACHE II – acute physiology and chronic health evaluation II; SOFA – sepsis-related organ failure assessment; ICU – intensive care unit; SHT – systemic hypertension; DM – diabetes melitus; COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD – chronic kidney disease; HF – heart failure; IC – ischemic cardiomyopathy; NIV – noninvasive ventilation.

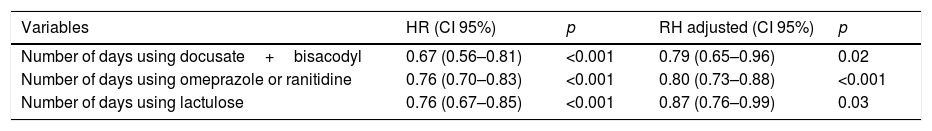

Although constipated patients used more lactulose (p=0.04) and docusate+bisacodyl (p=0.003), the introduction of these drugs was later (lactulose: 3 days, P25: 3, P75: 4 vs 1 day, P25: 1, P75: 2.5; p<0.001; docusate+bisacodyl: 5±1.7 vs 2±1.4 days after admission; p=0.02). It should be noted that only two non-constipated patients received docusate+bisacodyl. One of them started using in the first day of stay at ICU and the other in the next day. After adjustment, through multivariate Cox regression, none of those described in previous studies (use of opioids, vasopressors and enteral nutrition) or other clinical variables tested by us (APACHE, SOFA, use of MV, use of sedatives, use of neuromuscular blockade, comorbidities, immobility, among others), has been shown to be associated with the constipation risk. Table 2 shows the variables independently associated with constipation, adjusted to the time until the first evacuation in the ICU. We found that for each daily use of docusate+bisacodyl, omeprazole or ranitidine and lactulose, there was a reduction in the constipation risk (risk reduction of 21%, 20% and 13%, respectively).

Crude and adjusted hazard ratio for constipation.

| Variables | HR (CI 95%) | p | RH adjusted (CI 95%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of days using docusate+bisacodyl | 0.67 (0.56–0.81) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.65–0.96) | 0.02 |

| Number of days using omeprazole or ranitidine | 0.76 (0.70–0.83) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.73–0.88) | <0.001 |

| Number of days using lactulose | 0.76 (0.67–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.87 (0.76–0.99) | 0.03 |

In this cohort, constipation was a very incident event. We have not confirmed findings from previous studies regarding the association between clinical and treatment characteristics and the constipation risk. On the other hand, we demonstrated that days of drug use with a digestive tract action (lactulose, bisacodyl and omeprazole and/or ranitidine) prevent the outcome.

Studies evaluating the constipation incidence in critical care patients are heterogeneous and use different definitions to determine constipation. In six studies, the authors adopted the same criteria as us and found constipation incidences ranging from 9 to 96%.1,6,7,12,14,16 Differences in the profile of patients and in the design among these studies may explain this great variability. Three of these studies1,12,16 were also prospective cohorts, which enabled to establish comparisons. One of them followed clinical and surgical patients using MV,1 another study included only clinical patients12 and the third followed surgical patients from a Brazilian ICU.16 The constipation incidences were high (83%, 51.9% and 69.9%, respectively), as in the present study. In both studies1,12 where there was inclusion of surgical patients, there was more constipation, corroborating our finding of the univariate analysis that evidenced an association between surgical hospitalization and constipation.

Previous studies have also identified similar risk factors when using exclusively univariate analysis. An Indian study that prospectively followed 50 patients (aged between 12 and 55 years) found that fasting patients had more absence of daily evacuations than patients who consumed some type of diet: liquid, semi-solid or solid (78% vs. 40%, 37%, 33%, respectively, p<0.01).8 This data corroborates our finding of association between fasting time (days) and constipation.

Nguyen et al.10 prospectively included 248 patients admitted to three Canadian ICUs for ≥72h and who were undergoing MV and enteral nutrition. They evaluated the presence of “impaired gut transit” diagnosed by the frequency of evacuations and clinical manifestations. They found that the use of prophylactic treatment for constipation (senna, docusate, metoclopramide, domperidone or erythromycin) was more frequent in patients who did not show the disorder (86% vs 63%, p=0.002). However, after adjusting for confounding factors, the use of these drugs was identified as a risk for gastrointestinal transit disorder (OR: 3.5; CI95%: 1.4–8.8).10 Certainly, this finding is not related to the drug action, but to the objectives, indication and moment for its use. In the present study, the number of days in use of two types of laxatives were shown to be protective factors for constipation in critical care patients. It should be noted that in the ICU in question there is no protocol for the indication of prophylactic or therapeutic drugs to manage constipation, and the prescription is arbitrated by each doctor.

Sodium docusate is a emollient laxative that increases the water content of feces, thus producing softer consistency stools.18 Its efficacy in critical care patients is not documented in the literature. Furthermore, the efficacy of docusate in the treatment of constipation in individuals with chronic constipation is limited19,20 and its use has been discouraged.18 In the present study, docusate was used in combination with bisacodyl, which is a stimulant laxative whose action causes an increase in the contraction of the smooth muscle in the intestinal wall.19 Any specific studies evaluating the use of bisacodyl in critical patients are also available. A meta-analysis published in 2011,21 whose aim was to evaluate the efficacy of laxative treatments for individuals with chronic constipation, included two randomized clinical trials,22,23 integrating 735 patients with non-hospitalized chronic constipation. The authors identified that stimulant laxatives (sodium picosulfate and bisacodyl) needed to be used by three patients so that one of them keep at least three spontaneous evacuations per week (NNT: 3; CI95%: 2–3.5).21 It is unclear how long the evacuation process may depend on the use of these drugs. Thus, stimulant laxatives tend to be recommended for occasional use.19 Assessing the safety of long-term use is beyond the scope of this study, however, further studies may be useful to evaluate the use of stimulant laxatives in critical care patients.

In our study, the number of days in the use of lactulose was also indicated as a factor to protect against constipation, which is in line with the findings of the study by Bishop et al.9 In that cohort prospective at a general ICU in Australia, 44 patients using MV for more than 24h were included. The assessed outcome was not constipation, but the presence of evacuations over the days. Lactulose treatment was independently associated with the presence of daily evacuation (p=0.009).9 Corroborating our findings, previous studies3,6,7 demonstrated the efficacy of lactulose in promoting evacuations and preventing constipation in critical care patients. Azevedo et al.6 conducted a randomized clinical trial that assessed the effects of laxative treatment on the incidence of constipation and the association between failure to evacuate and organ dysfunction in patients under MV in a general ICU. The intervention group consisted of patients who received enema and/or lactulose to promote one or two evacuations per day, while any evacuation was tolerated for up to five days in the control group. The intervention group showed a greater reduction in SOFA from admission to SOFA on discharge from ICU, or after 14 days of follow-up (−4, P25: −6, P75: 0 vs −1, P25: −4, P75: 1; p=0.036), suggesting that the intervention may be associated with a greater reduction of the organic dysfunction.

Van der Spoel et al.3 published a randomized clinical trial that evaluated the impacts of laxatives: lactulose and polyethylene glycol in early evacuations. These authors showed a shorter stay in ICU hours for the lactulose group (156, IQ: 178 vs 196, IQ: 277; p=0.016). Another study conducted by Masri et al.7 randomized 100 patients to receive/not receive lactulose during the first three days of ICU stay as prophylaxis for constipation. In the control group, only two (4%) patients evacuated in less than 72h, while nine (18%) patients in the intervention group evacuated during this period (p<0.05). In our study, it was also observed that only 38 (24.2%) patients evacuated until the third day; from these, 13 were using lactulose.

Stress ulcer prophylaxis is often adopted in critically ill patients.24 The literature does not present studies on the use of omeprazole or ranitidine and its association with the subject of constipation in the adult critical care patients. One hypothesis that may be considered is the action mechanism of omeprazole and ranitidine. Gastric acid is a natural physiological barrier against ingested pathogens; the pharmacological suppression of this acid, produced by these medications, changes this barrier significantly,25,26 which may promote bacterial colonization in the gastrointestinal tract, increasing the infection risk.27 A meta-analysis that included 39 studies showed a 74% increased risk of developing Clostridium difficile infection, as well as a 2.5-fold increased risk of recurrent C. difficile infection compared to non-users of proton-pump inhibitors, such as omeprazole.28 Based on these data, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published a safety alert in 2015 on the association of proton-pump inhibitors and C. difficile infection.28 Although not an expected event, this change in intestinal microbiota may be related to the presence of evacuations, which could explain the finding of this study. In our cohort, any patients with C. difficile infection were identified. Omeprazole and ranitidine were evaluated together, so it is not possible to determine if the protective effect is different for one of the medications. Further studies are needed to better elucidate this finding.

Although cohort studies, especially those of contemporary temporality, are the best design for understanding the independent effect of outcome predictors, variables that were not predicted in the planning cannot be analyzed.17 In the present study, a large number of variables related to the treatments attributed in the ICU and the patient's clinical conditions were evaluated. Nevertheless, it was not possible, with the sample and with the adopted type of statistical analysis, to establish risk variables for constipation. However, due to the expected effect of the use of laxatives and proton-pump inhibitors, the use of these drugs was protective for constipation.

ConclusionThe incidence of constipation in adult critical care patients is high. The number of days using the gastrointestinal tract: docusate+bisacodyl, lactulose and omeprazole and/or ranitidine, adjusted for the number of days until evacuation, are independent of protective factors for constipation.

Financial supportFundo de Apoio à Pesquisa of Hospital de Clinicas de Porto Alegre.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank Franciele Anziliero, Rani Simões de Resende, Giovana Capellari and especially Barbara Amaral da Silva and Barbara Elis Dal Soller for their collaboration.

Institution where the work was performed: Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre – South of Brazil.

Please cite this article as: Batassini É., Beghetto M.G. Estreñimiento en una cohorte prospectiva de adultos críticos: porcentaje y motivo de su incidencia. Enferm Intensiva. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfi.2018.05.001