The aim of this paper is to determine the incidence and most incident pressure ulcers (PU) category. Establish the main clinical characteristics of these PU. Determine whether there is adequate documentation of PU and of the measures used to prevent them.

MethodObservational descriptive and retrospective study during 2014 at Intensive Care Unit (ICU)-University Hospital of Araba. Study sample, all patients suffering from PU at the time of the study by accidental sampling.

Computerised records regarding risk assessment, clinical assessment and pressure sore treatment, provided by the ‘Metavision’ computer programme and descriptive statistics using SPSS version 22.0. Approval from the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of the University Hospital of Araba was obtained.

ResultsThe incidence of patients suffering from PU during 2014 was 6.78%. The most common locations for PU were the sacral region and the heels: the most incident pressure ulcers category was grade II, followed by grade I. Out of the 98 PU treated in our patients, 43 occurred outside the ICU and 55 in the unit itself. The lack of records, in all the variables described about PU, was 19.10%.

ConclusionsThe incidence of pressure ulcers was lower than in the current literature. The most frequent category, location and clinical characteristics are comparable to previous studies. There is a high rate of failing to record the characteristics of the PU declared. Good PU prevention measures and recording were carried out.

Determinar la incidencia y categoría más incidente de úlceras por presión (UPP). Conocer las características clínicas de las UPP. Determinar si se realiza un registro adecuado de UPP y las medidas de prevención utilizadas.

MétodoEstudio observacional, descriptivo y retrospectivo realizado durante el año 2014 en la UCI del Hospital Universitario Araba (HUA)-Txagorritxu. La población de estudio fueron todos los pacientes ingresados con UPP, obtenidos mediante muestreo accidental. Los datos se recogieron a través de los registros informatizados del programa Metavisión de valoración del riesgo, valoración clínica y tratamiento de UPP, los cuales se analizaron con estadística descriptiva y se procesaron mediante el paquete estadístico SPSS, versión 22.0. El estudio fue aprobado por el Comité Ético de Investigaciones Clínicas del HUA.

ResultadosLa incidencia de pacientes con UPP durante el 2014 alcanzó el 6,78%. La localización de UPP más frecuente fue en la zona sacra y en los talones. La categoría de UPP más incidente fue la II, seguida de la I. De las 98 UPP tratadas en nuestros pacientes, 43 se produjeron fuera del servicio y 55 en la UCI del HUA. La ausencia de registro, en todas las variables descritas sobre las UPP, fue de un 19,01%.

ConclusionesLa incidencia de UPP alcanzó un porcentaje inferior a lo existente en la literatura actual. La categoría, localización y características clínicas más frecuentes se asimilan a estudios previos. Existe una elevada tasa de no registro de las características de las UPP declaradas. Se efectuaron unas buenas medidas de prevención de UPP y registro de las mismas.

The National Advisory Group for the Study of Pressure Ulcers and Chronic Wounds (GNEAUPP) suggests that pressure ulcers (PU) should be defined as “an injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear. They may also occasionally appear on soft tissues subjected to external pressure by different materials or clinical devices”.

The incidence of PU in Intensive Care Units (ICU) is still very high. The intensive care unit is one of the departments that invests highly on prevention resources; even so, PUs remain a notably serious health problem.

We know that PUs are caused by pressure, therefore it is difficult to understand why under the same conditions and with the same risk factors, applying the same prevention measures, some people will develop PU and others will not, and why when they occur they manifest in different ways. Similarly, records are a major aspect to be considered to measure the real extent of this health problem in our critical care units.

This paper provides information on the incidence, characteristics and prevention of PUs in a critical care setting.

Implications of the studyAnalysis of the results of the study enabled us to determine the current status of this health problem and to enable various measures to be planned and implemented; to reduce the incidence of these types of dependency-related wounds implementing the Braden scale to assess pressure ulcer risk, improving the material available on PU prevention and undertaking continuous education in the prevention and treatment of chronic wounds. Likewise, a new prevention protocol was implemented in the unit. Three subsequent studies or lines of investigation emerged from this study within the department.

Pressure ulcers (PUs) are a major public health problem that affects millions of people worldwide disrupting their health and quality of life and can result in disability or death.1

As is to be expected, with the advancement of science, the definition of PU has changed in recent years. One of the most recent definitions is “an injury to the skin and/or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear. A number of contributing or confounding factors are also associated with pressure ulcers; the significance of these factors is yet to be elucidated”. This description was taken on jointly in 2014 by the North American National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP), the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), and the Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA).2

There has been intense debate in recent years about whether the pressure ulcers that bedridden and immobile patients develop are really caused by pressure or by other elements, such as humidity or friction.3 We know that PUs are caused by pressure, therefore it is difficult to understand why under the same conditions and risk factors, using the same prevention measures, some people will develop a PU and others not, and why when they appear they manifest in different ways.

In 2003, Verdú et al. observed adjusted rates of up to 20 deaths per 100,000 male inhabitants, and up to 31 per 100,000 female inhabitants, according to the autonomous region and period of study, caused by PU.4

In these times of financial crisis, prevention is considered more cost-effective, as shown by several studies. In Holland, using preventive measures based on the evidence at the time to reduce the prevalence and incidence of PU, also enabled costs savings of between 78,500 and 131,00 per year.5

PUs imply major consumption of both human and material health resources; they lengthen hospital stays and are responsible for significant social and health costs. The real situation in Spain, after extrapolating data obtained in the United Kingdom, was reflected in a study performed in 2007 indicating that around 5% (estimated at 1687 million Euros) of the total health expenditure was spent on treating PU.6

According to the literature provided by the 4th International Study, the prevalence of PU in intensive care units (ICU) is 22% (95% CI: 15.44–22.02).7 The incidence of PU is used as a quality criterion in ICUs; they cause health problems in individuals and reduce the quality of patient care with legal repercussions, since onset of PU is considered professional negligence.8,9 The latest studies on the incidence of PUs in intensive care units show an incidence of 13.72%.10 According to the EPUAP, NPUAP and PPPIA (2014),2 incidence is the best epidemiological indicator to analyse this health problem.

Intensive care units are areas where patients are exposed to many risks. The special conditions of patients admitted to intensive care units, such as sedation, mechanical ventilation, vasoactive drugs, renal clearance, nutritional status, etc., make them highly vulnerable to PUs.11 We know, according to data provided by the SYREC report, that PUs are one of the most frequent adverse effects relating to nursing care provided in intensive care units.12

The prevention of PU includes, assessment of PU risk, special support surfaces, actions to prevent friction or shear injury, moisture, and nutritional deficiencies are currently the most important recommendations.13 Special support surfaces are have been confirmed as a key tool in reducing the incidence of PU.14–24 Systematic recording of grade I PUs is considered essential since 13.7% progress to higher grades.25

ObjectivesThe objectives proposed are as follows:

- •

To determine the incidence of PUs in the ICU of the University Hospital of Araba, Txagorritxu (HUA-Txagorritxu).

- •

To analyse the clinical characteristics of PUs in ICU.

- •

To examine the extent to which the sections of PU records are completed in the ICU of HUA-Txagorritxu.

- •

To determine the measures and resources in place for PU prevention in HUA-Txagorritxu ICU.

An observational, descriptive and retrospective study was undertaken.

ScopeThe study was undertaken in the ICU of HUA-Txagorritxu from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2014. This is a polyvalent ICU with 18 beds, which can extend to 20 beds, of a referral hospital (Araba integrated health organisation, University Hospital Txagorritxu [HUA-Txagorritxu]) for the health areas of Mondragón (Guipuzkoa), Miranda de Ebro (Burgos), Logroño (La Rioja) and the region of Araba. The hospital provides health services to more than 300,000 people.

SubjectsAll the patients who developed a PU in HUA-Txagorritxu ICU during the 2014 calendar year were studied, through accidental sampling, excluding patients under the age of 18 years and those with a PU originating from outside the ICU and who developed no further PU during their stay in ICU.

VariablesThe design of this study does not enable identification of causal relationships between the different factors.

To establish the study variables, we referred to those published by the National Advisory Group for the Study of Pressure Ulcers and Chronic Wounds (GNEAUPP) in 2012, i.e., the minimum basic data set (MBDS) in PU records.26 In general, the declaration form included the variables according to the MBDS, divided into 3 large groups: general information on the characteristics of the unit where the study was undertaken; characteristics of the patients with PU, and the unit's PU prevention strategies. These are our study variables:

- •

Sociodemographic and clinical variables: age, sex, days of admission, re-admission, disease on admission (cardiorespiratory arrest, digestive surgery, vascular surgery, respiratory disease, digestive disease, kidney disease, endocrine disease, multiple organ failure, sepsis), implementation of invasive measures.

- •

Principal variables relating to PUs: the information to be gathered and the definition of the presence of PUs and all their characteristics were based on the criteria established by the GNEAUPP.26,27

- •

In addition, the total number of PUs was collected, the number of PUs originating outside and inside the ICU.

- •

PU preventive measures:

- ∘

Identification of PU risk: the Gosnell scale adapted by Osakidetza was used.

- ∘

Preventive measures applied to each patient: position changes, early sitting, hyper-oxygenated fatty acids (HOFA) on pressure areas, washing with neutral soaps, urea cream moisturising at each shift, special support surfaces.

- ∘

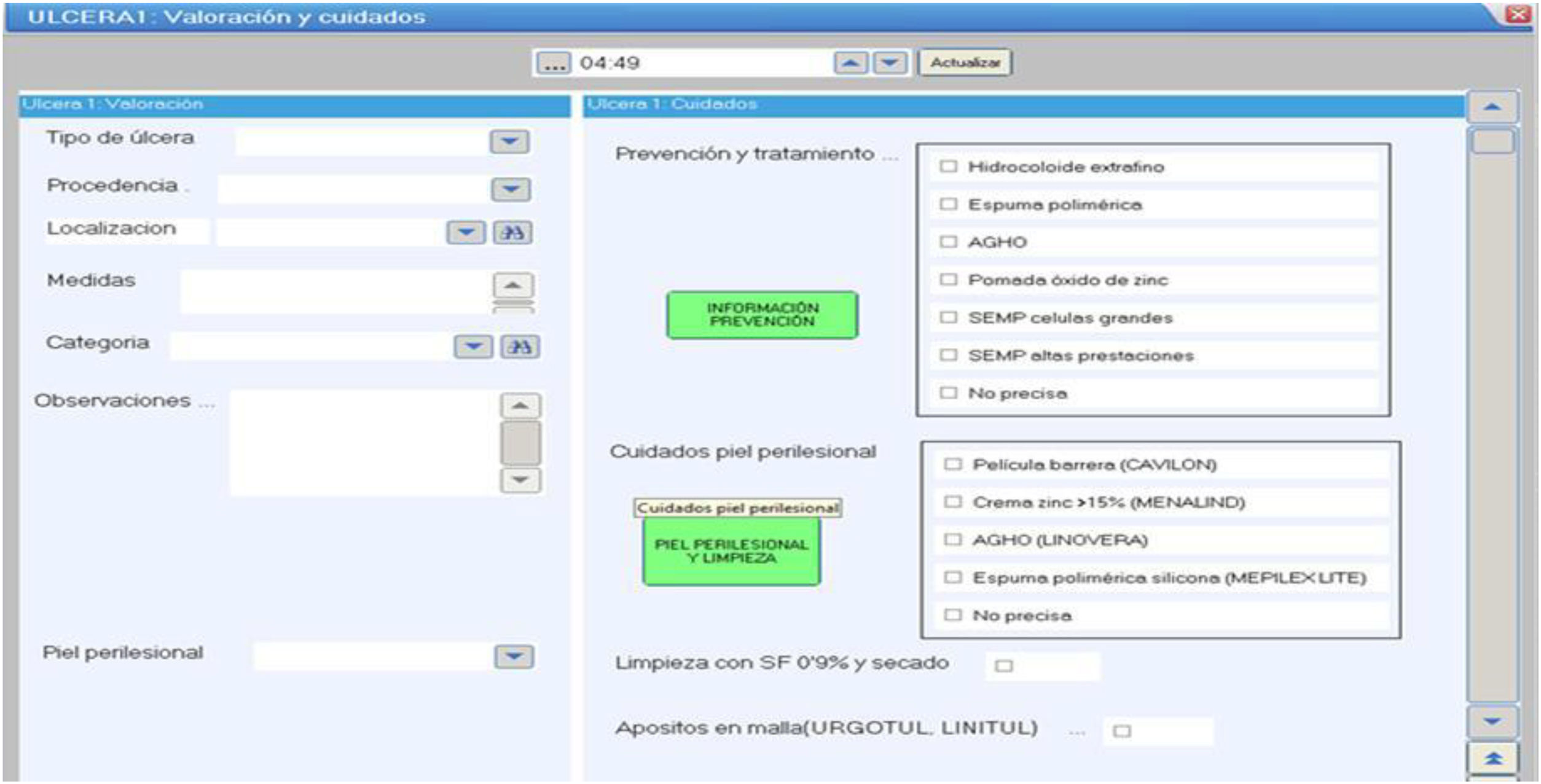

The data was extracted by the principal investigator retrospectively from the databases generated in the unit's digital clinical record. The different characteristics were recorded by the nursing team of HUA's ICU over the study period and according to routine practice. These data are recorded on our unit's computer tool form, called MetaVision, which is clinical software developed for ICUs to record nursing care, treatment, medical care and much patient data such as vital signs, data on mechanical ventilation, etc. Similarly, all the information collected is based on the MBDS of the PUs, and their care, also recorded in the abovementioned software (Fig. 1). The data are sent on to an Excel database for subsequent analysis.

Data analysisDescriptive statistics were used in the main in the analysis of the information in order to meet the objectives set. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for one sample was used to examine the normality of distribution of the variables in the sample. According to this test, the quantitative variables were described using means and standard deviation if there was normality, and the mean and interquartile range if not. The qualitative variables were described in absolute and relative frequencies. The incidence of patients with a PU was calculated. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22.0, was used to process the data.

Ethical considerations of the research studyThis Project was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Araba (File number: 2015/004) on 23/01/2015.

The data were stored on an SPSS version 22.0 database in compliance with the privacy standards established in Organic Law 15/1999, of 13 December, on Personal Data Protection.

Even so, the relevant permits were requested from HUA's nursing management and their subsequent authorisation.

ResultsDuring 2014, of the 811 patients admitted to ICU, 98 were identified with a recorded PU: 43 were detected on admission, and therefore had developed outside the ICU (none of the subjects studied had more than one PU). The results are presented below.

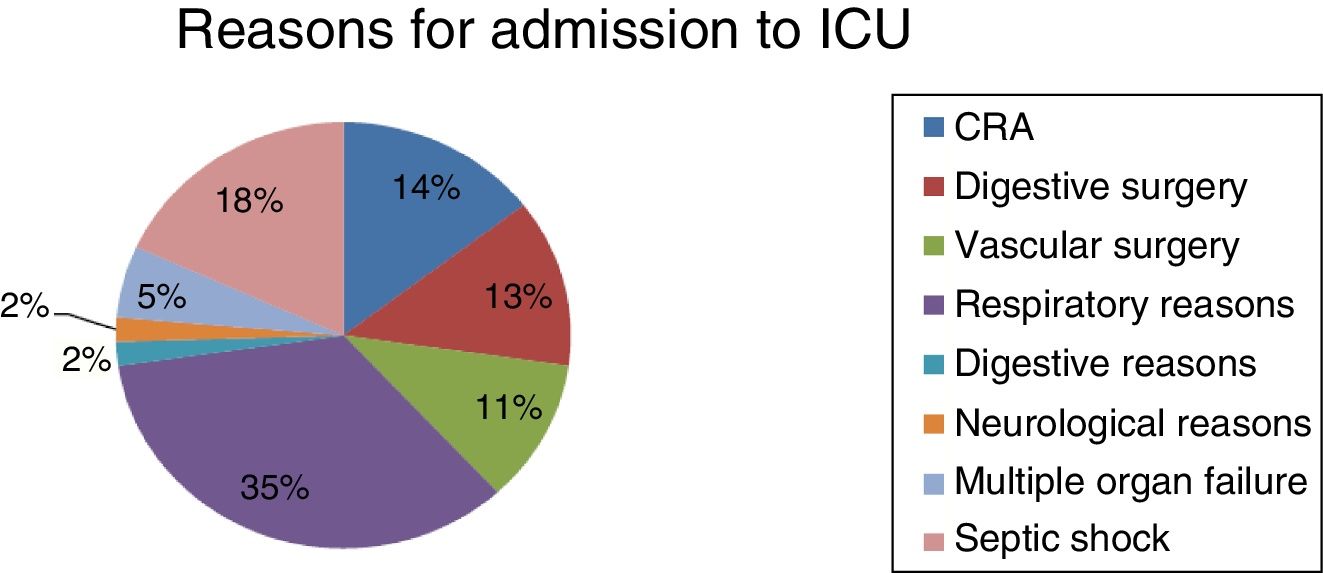

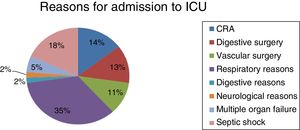

The median age of these patients was 72 years (interquartile range=18 years), there was a predominance of males (80%). The median stay for this group of patients was 14 days (interquartile range=18 days), and there was 45.5% re-admission to ICU during 2014. The distribution of the reasons for admission to ICU are shown in Fig. 2. None of the days of PU onset were recorded during the patients’ admission to ICU.

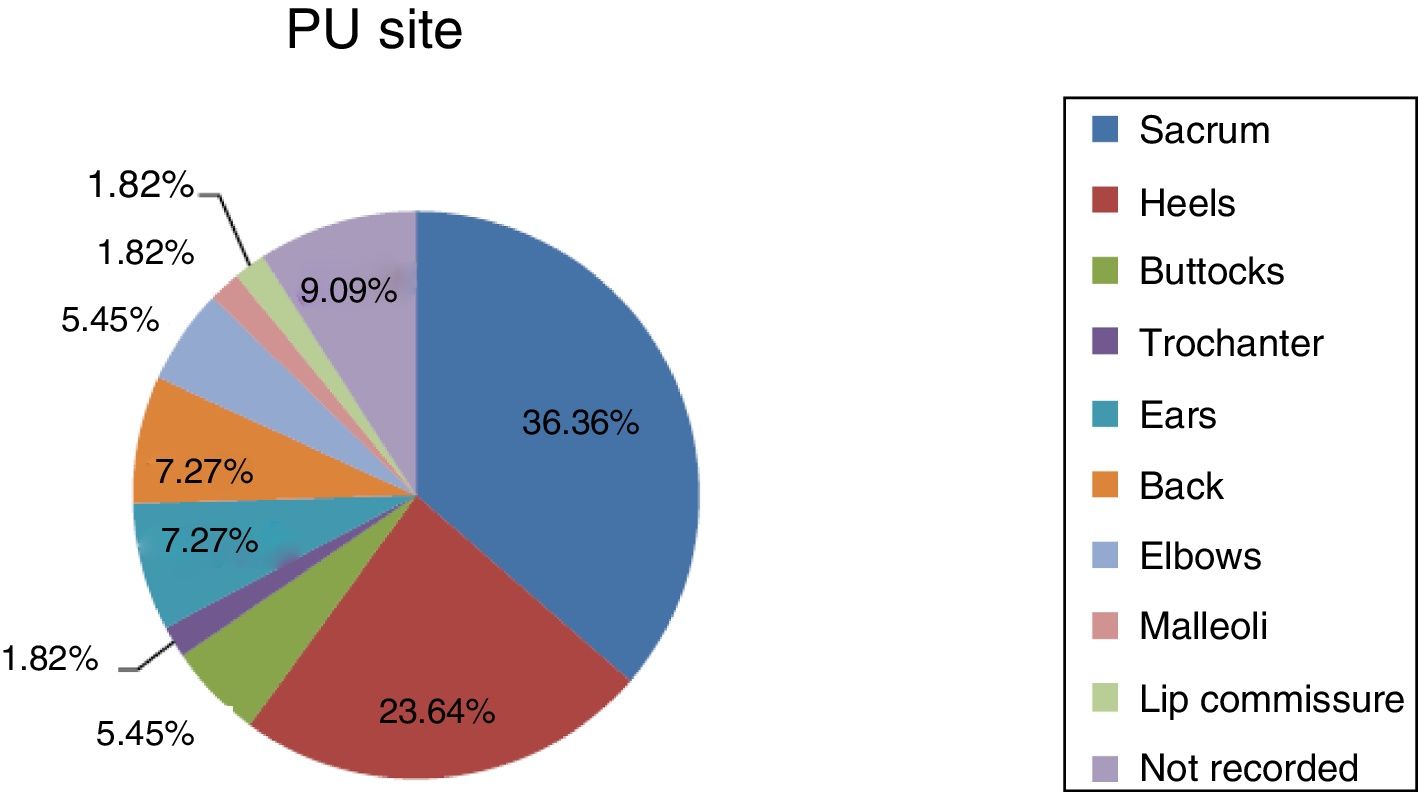

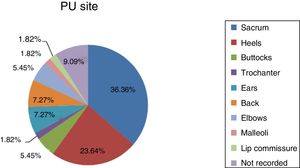

The incidence of patients with PUs during 2014 in the ICU was 6.78%, with a predominance of grade II PUs (52.73%), followed by grade I (43.64%), and then grades III and IV of the same frequency (1.82%). Fig. 3 shows the distribution of the location of the PUs.

Only one grade III and one grade IV PU were identified. Of these, the grade IV PU had epithelialized tissue and the grade III PU had no record of the peripheral skin. Neither had exudate and there was no record of pain or odour.

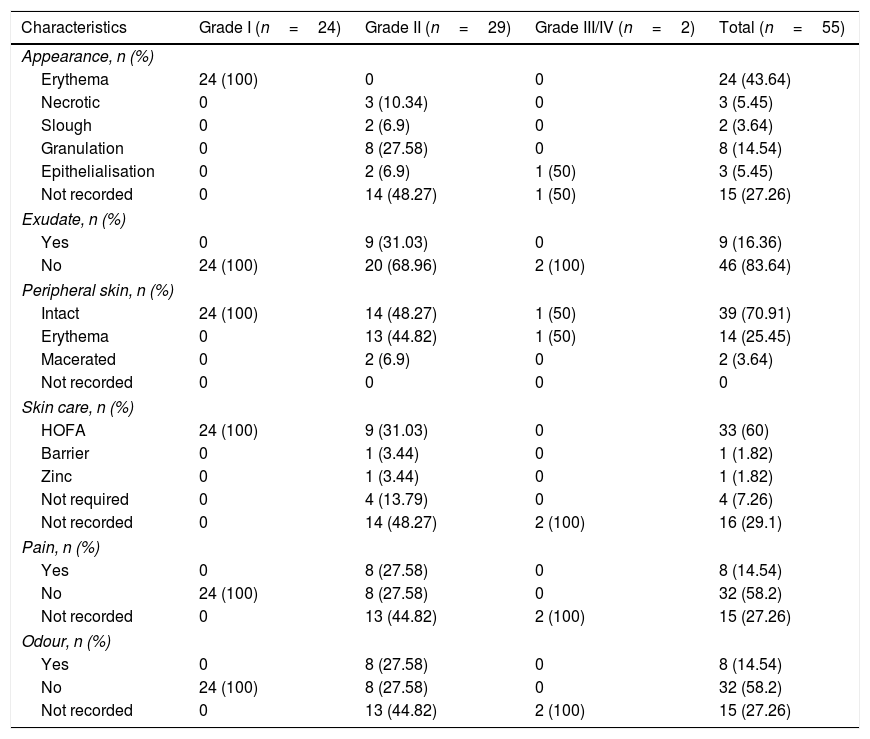

In general, the majority (43.2%) of the grade I and II PUs were around 0–5cm2, although there was no record of measures for 41.82%. No case of bleeding was documented, but this data was not recorded in 32.73% of the cases. A similar situation occurred with recording of infection; no cases of infection were detected, but non-recording was 13.36%. Other data on the characteristics of these PUs are shown in Table 1.

Results of the PU characteristics.

| Characteristics | Grade I (n=24) | Grade II (n=29) | Grade III/IV (n=2) | Total (n=55) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance, n (%) | ||||

| Erythema | 24 (100) | 0 | 0 | 24 (43.64) |

| Necrotic | 0 | 3 (10.34) | 0 | 3 (5.45) |

| Slough | 0 | 2 (6.9) | 0 | 2 (3.64) |

| Granulation | 0 | 8 (27.58) | 0 | 8 (14.54) |

| Epithelialisation | 0 | 2 (6.9) | 1 (50) | 3 (5.45) |

| Not recorded | 0 | 14 (48.27) | 1 (50) | 15 (27.26) |

| Exudate, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 9 (31.03) | 0 | 9 (16.36) |

| No | 24 (100) | 20 (68.96) | 2 (100) | 46 (83.64) |

| Peripheral skin, n (%) | ||||

| Intact | 24 (100) | 14 (48.27) | 1 (50) | 39 (70.91) |

| Erythema | 0 | 13 (44.82) | 1 (50) | 14 (25.45) |

| Macerated | 0 | 2 (6.9) | 0 | 2 (3.64) |

| Not recorded | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin care, n (%) | ||||

| HOFA | 24 (100) | 9 (31.03) | 0 | 33 (60) |

| Barrier | 0 | 1 (3.44) | 0 | 1 (1.82) |

| Zinc | 0 | 1 (3.44) | 0 | 1 (1.82) |

| Not required | 0 | 4 (13.79) | 0 | 4 (7.26) |

| Not recorded | 0 | 14 (48.27) | 2 (100) | 16 (29.1) |

| Pain, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 8 (27.58) | 0 | 8 (14.54) |

| No | 24 (100) | 8 (27.58) | 0 | 32 (58.2) |

| Not recorded | 0 | 13 (44.82) | 2 (100) | 15 (27.26) |

| Odour, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 8 (27.58) | 0 | 8 (14.54) |

| No | 24 (100) | 8 (27.58) | 0 | 32 (58.2) |

| Not recorded | 0 | 13 (44.82) | 2 (100) | 15 (27.26) |

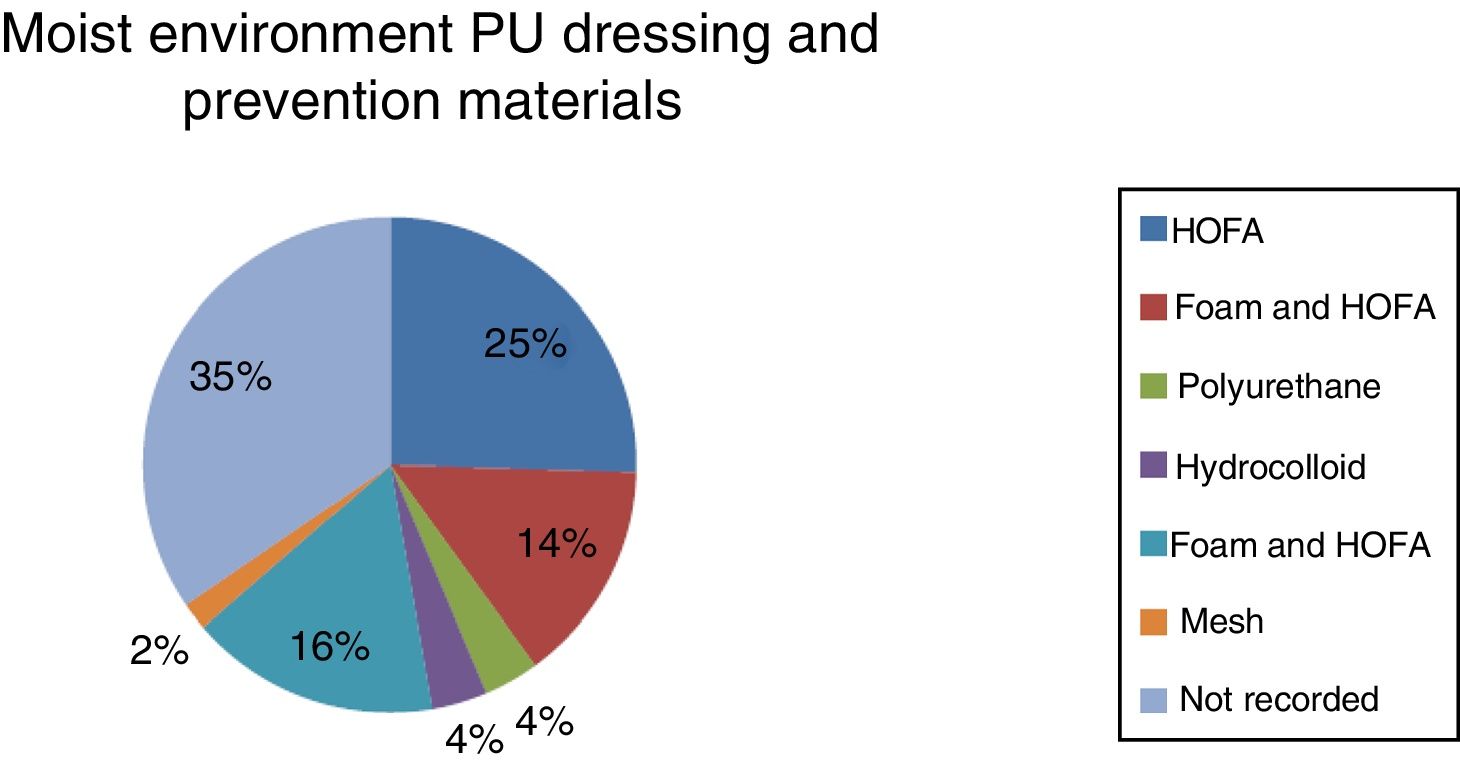

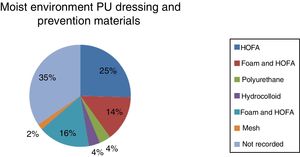

Of the PUs, 71% required no debridement of any type. Only 4 PUs required debridement: one autolytic and 2 enzymatic, for the grade II PUs; for the remainder there was no record of the type of debridement. This data was not recorded in 23.64%. Regarding other types of treatment, in all cases when the PUs needed dressing this took was a moist environment dressing. The distribution of the materials used for dressing and prevention of PUs are shown in Fig. 4.

With regard to the current measures and resources for PU prevention in the HUA-Txagorritxu ICU, the data obtained on PU risk, measured using the Gosnell scale adapted by Osakidetza, on admission only tell us that the median for the patients studied was 11 points (interquartile range=4). Sixty-two percent had a score below or equal to 11 (high risk), and 38%, moderate risk. None of the patients had a score above 18 on the scale (low risk). All the items of the PU risk assessment on admission were completed, since this is compulsory in the digital medical record. We did not study successive PU risk assessments, only on admission.

The preventive measures used for each patient were recorded on the digital nursing record (MetaVision).

- •

Position changes for patients at moderate or high risk, every 3h: 100% recorded.

- •

Early sitting in morning and afternoon shifts: 100% of the patients who were stable at respiratory and haemodynamic level.

- •

HOFA on pressure areas and protection: patients at low risk during the morning shift, 100%. Once during each shift for patients at moderate and high risk: 100%.

- •

Washing with neutral soaps during the morning shift and hydration each shift with urea cream: 100% recorded.

- •

We have 18 special support surfaces (8 powered and 10 nonpowered) in the unit. We also have 2 nonpowered cushions and one powered cushion to help patients sit. According to the PU risk obtained on admission, the patients with a high or moderate risk were given powered support surfaces and those with a low risk, nonpowered support surfaces. There is no record of which patients were allocated a special support surface.

The first data on ICU incidence were provided by Bergstrom, an American nurse; the incidence was 40% in 1987.28

Overall in Spain, the latest national studies on prevalence give an idea of the magnitude of this problem, which rose from 13.16% (2001) to 21.05% (2006), until 24.20% (2009), 22% (2013) in critical care units.7,29–31

The incidence of patients who developed a PU during the study period was 6.78% in our unit, given the variability of the current literature, we consider this a similar figure to that of other national and international ICUs. If we argue that 95% of PU can be prevented with an appropriate protocol with prevention measures, our current results should improve.

With regard to how the incidence is evolving in HUA-Txagorritxu ICU, we must mention that the current figure is higher than that of previous years, due in part to the change in medical records and PU recording support from paper to software using Metavision, which has improved quantitative and qualitative recording. In addition, the quality of the epidemiological data measurement process has increased, although it could be improved further.

Previous studies on incidence show similar data to ours, such as that by Roca Biosca et al. (11.03%),32 Almirall Solsona et al. (12.5%),33 Kaitani et al. (11.2%).34 However, other research studies have shown higher incidences: Manzano and Corral (16%)35 and Fuentes Pumarola et al. (20.5%)36 in Spain.

Díaz de Durana et al.37 contribute to the literature that, from 2000 to 2005, in the ICU of Txagorritxu Hospital, now HUA-Txagorritxu, the incidence of PUs was as follows: 2000 (0.58%), 2001 (0.10%), 2002 (0.60%), 2003 (1.69%), 2004 (1.50%), 2005 (1.35%).

The most common PU sites, in our study, were the sacral region and the heels in line with various studies. Other studies report that other common areas are the face (ears, lip commissure, etc.), caused by breathing devices and their attachments.7,29–31,38,39

There was a higher incidence of grade II PUs. This leads us to believe that we should intensify the inspections we carry out during daily washing of these patients; thus we would be able to detect more grade I PUs and use the entire range of products available and demonstrated as effective through various studies40–43 for the care of this damaged skin (HOFA, barrier products, etc.). We report in the data we obtained that 100% of the patients with a grade I PU were treated with HOFA and pressure management.

We believe, according to the recommendations of the GNEAUPP 2012, on MBDS in PU records26 and through the data provided, that there is no detailed recording of PUs, since 19.01% of the data of the variables gathered in our study were not recorded.

In a more thorough analysis, in the description of one of the grade II PUs no slough or necrotic tissue were recorded. We believe that it was poorly graded due to a lack of training or an error in its recording.

With regard to recording of the type of debridement, in the results it was described that of the 4 PUs recorded with non-viable tissue that required debridement, autolytic debridement was used for a grade II PU, enzymatic debridement for 2 grade II PUs, the treatment used was not recorded for the remaining PUs. Like the abovementioned case, either there was an error in grading the PU, or an error in recording it, since these types of ulcers do not require debridement given their intrinsic characteristics.

For the PU surface measurement variable, there is obviously great variability, either because each ulcer and patient are different, or due to poor recording, or a failure to use the correct measurement technique.

We have detected that there is no record of the treatment used specifically to alleviate the pain of these PUs.

Given all these statements, we believe there should be improved recording of PU characteristics and training of our professionals and propose a protocol for the treatment of PU pain.

Regarding PU prevention, it is known that PU risk assessment scales (PURAS) are useful as tools that can measure the risk of a patient in ICU developing a PU and guide us to which prevention measures to use. Before this study, a cross-sectional study was undertaken in our unit, coordinated by Rodríguez Borrajo (2015),44 on the extent of completing and updating PURAS in HUA-Txagorritxu ICU, which obtained the following results: the risk of ulcers was assessed on average every 6.68 days, only 28.95% of the assessments were updated, and only 23.68% of the patients had more than one completed scale. These figures are at odds with this study, since we only researched the PURAS on admission and 100% were completed because it is compulsory.

Therefore, we must promote good practice in the unit, when we are failing to use correctly one of the highly recommended measures based on current usage of PURAS and with the frequency recommended in ICUs. A good measure would be to implement PU risk assessment in our unit as recommended in the current references every 24h and continuously if the patient's condition changes. This assessment process requires at least 2 independent studies to confirm its interobserver validity and reliability.45

We need to consider whether the general, validated PURAS are indicated for ICUs or whether it would be better to use more specific scales for these types of patients even if they have not been validated.

Currently, in adult intensive care units, only 7 scales have been validated for use in critical patients. The Cubbin-Jackson, Norton Mod. Bienstein and Jackson-Cubbin scales are specific to ICU; Norton, Waterlow, Braden and BradenMod. Song-Choi are among the general scales used in these departments.46

There are scales such as EVARUCI (current assessment scale of the risk of developing pressure ulcers in intensive care units) that have now been validated. This is the only specific scale for critical patients created in Spain.38,47,48

Gosnell's scale adapted by Osakidetza has been used for years in our hospital's ICU. Given the above analysis of current evidence and the clinical setting where we deliver health care, we suggest a change of PURAS. In a review of the current literature, it is the Braden scale that has been most thoroughly validated in ICU. It has a good balance between sensitivity, negative predictive value (NPV), efficacy and relative risk (RR) with a narrow confidence interval. Reliability has been measured using statistical methods that provide good interobserver reliability.46 It is also the PURAS used in the other ICUs of the Osakidetza network.

According to the PU prevention recommendations of GNEAUPP,15 our unit implements the relevant preventive measures based on current available evidence, but according to the abovementioned results we need to improve on prevention and, above all, recording.

Likewise, our senior management in HUA should be persuaded to invest in prevention, intensify training and keep evidence-based protocols updated, and the nursing team (nurses and nursing assistants) should be aware that although critical patients with their characteristics and associated risk factors are totally dependent on our care, prevention is the essential measure for this serious health problem, where we can prevent 95% of cases by using the currently available protocols and clinical practice guidelines.

Specific training sessions have been held on PU prevention and treatment in our unit due to the shortfalls detected in this study. Likewise, shortfalls in the knowledge on PU prevention and care in critical care units have been detected in previous published studies.49–54

Limitations of the study include the difficulties in data collection; this might have been due to the design of the medical history form, which might have affected the results. Furthermore, we can highlight the variability in how the wounds were graded throughout that year. In other words, were all the PUs declared really caused by pressure? Or were there other causes which were declared as PU?

Moreover, not all the PU (especially those of grade I) were declared, since some of the unit's professionals did not consider it necessary to declare them, probably due to the lack of training in the area of PU prevention and treatment. We assume a possible selection bias, intrinsic to incidence studies.

ConclusionsThe main results obtained in this study were:

- 1.

The incidence of patients who developed a PU in the ICU of HUA-Txagorritxu during 2014 was 6.78%, lower than the national average.

- 2.

The characteristics of the PU were like those of previous published studies.

- 3.

There is clear room for improvement in recording the variables described for PU, except in the preventive measure variable, since this is automatically recorded when nursing care of the skin is signed.

- 4.

The provision of special support surfaces, of which 44.44% are powered and 55.55% are nonpowered, is a good tool to prevent onset of PUs. In addition, thanks to combined cataloguing throughout the Osakidetza entity, the PU prevention materials recommended by the GNEAUPP (HOFA, polyurethane foams, etc.) are available in the unit's main warehouse, but not near the professionals inside the unit.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Núñez C, Iglesias-Rodríguez A, Irigoien-Aguirre J, García-Corres M, Martín-Martínez M, Garrido-García R. Registros enfermeros, medidas de prevención e incidencia de úlceras por presión en una Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos. Enferm Intensiva. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfi.2018.06.004