To determine the grade of sedation in the critically ill paediatric patient using Biespectral Index Sensor (BIS) and to analyse its relationship with sociodemographic and clinical patient variables.

MethodsObservational, analytical, cross-sectional and multicentre study performed from May 2018 to January 2020 in 5 Spanish paediatric critical care units. Sex, age, reason for admission, presence of a chronic pathology, type and number of drugs and length of stay were the sociodemographic and clinical variables registered. Furthermore, the grade of sedation was assessed using BIS, once per shift over 24 h.

ResultsA total of 261 paediatric patients, 53.64% of whom were male, with a median age of 1.61 years (0.35–6.55), were included in the study. Of the patients, 70.11% (n = 183) were under analgosedation and monitored using the BIS sensor. A median of BIS values of 51.24 ± 14.96 during the morning and 50.75 ± 15.55 during the night were observed. When comparing BIS values and sociodemographic and clinical paediatric variables no statistical significance was detected.

ConclusionsDespite the limitations of the BIS, investigations and the present study show that BIS could be a useful instrument to assess grade of sedation in critically ill paediatric patients. However, further investigations which determine the sociodemographic and clinical variables involved in the grade of paediatric analgosedation, as well as studies that contrast the efficacy of clinical scales like the COMFORT Behaviour Scale-Spanish version, are required.

Determinar los niveles de sedación del paciente crítico pediátrico mediante el sensor BIS y analizar la relación entre grado de sedación y las variables sociodemográficas y clínicas del paciente.

MétodosEstudio observacional, analítico, transversal y multicéntrico de mayo de 2018 a enero de 2020 realizo en cinco Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos Pediátricas del territorio español. Se registraron como variables sociodemográficas y clínicas el sexo, la edad, motivo de ingreso, si el paciente tenía patología crónica, tipo y número de fármacos que se le estaba administrando. Además, se anotaron los valores del BIS una vez por turno, mañana y noche, durante 24 h.

ResultadosSe incluyeron en el estudio un total de 261 pacientes, de los cuáles el 53,64% eran del sexo masculino, con una edad mediana de 1,61 años (0,35–6,55). El 70,11% (n = 183) estaban analgosedados y monitorizados con el sensor BIS. Se observó una mediana en las puntuaciones globales de BIS de 51,24 ± 14,96 en el turno de mañana y de 50,75 ± 15,55 en el de noche. No se detectó significación estadística al comparar los niveles de BIS y las diversas variables sociodemográficas y clínicas del paciente crítico pediátrico.

ConclusionesA pesar de las limitaciones inherentes al sensor BIS, los estudios existentes y el que aquí se presenta muestra que el BIS es un instrumento útil para monitorizar el grado de sedación en el paciente crítico pediátrico. Se requieren más investigaciones que objetiven qué variables relacionadas con el paciente tienen más peso en al grado de analgosedación y que contrasten clínicamente la eficacia de escalas como, por ejemplo, la COMFORT Behavior Sclae-Versión española.

The assessment of the degree of analgesia and sedation during comprehensive care of the critically ill paediatric patient is of vital importance if we are to decrease adverse events. The Bispectral Index Sedation (BIS) is a useful tool to determining the degree of sedation in the critically ill paediatric patient.

What does this paper contribute?No research has been found in the scientific literature that, like the one presented here, addresses the relationship between sociodemographic and clinical variables of patients admitted to paediatric intensive care units and their degree of sedation.

Implications for practiceAll the patients analysed exhibited a suitable level of sedation; consequently, their management in the paediatric intensive care units analysed was adequate. Despite not finding any statistical significance between certain sociodemographic and clinical variables of the paediatric patient in the present study, this investigation lays the groundwork for future research to explore the impact of the distinct characteristics of the critically ill paediatric patient and the need for analgesics and sedatives.

During the comprehensive care of a paediatric patient admitted to a paediatric intensive care unit (PICU), it is vitally important to ensure the correct management of analgesia and sedation,1 given that it impacts the quality and safety during the entire care process.2

In this regard, the Society of Paediatric Intensive Care (SECIP) defines analgesia as the “abolition of the perception of pain in response to stimuli that would normally produce it, but without the intention of producing sedation, which, if it occurs, will be as a side effect of the analgesic medication”.3 Therefore, analgesia reduces the pain caused by invasive procedures or by the disease itself.4,5

Managing the comfort of the critically ill patient admitted to a PICU, understood as proper pain control and optimal sedation, is an essential aspect that any professional working in these areas must bear in mind. The importance of monitoring the degree of pain and sedation is determined by the scientific evidence available in this field, which confirms the direct relationship between the adequate use of drugs and the duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU stay, the presence of nosocomial complications, and even mortality.6–11 Such management should begin with adequate pain assessment and treatment. Only once it has been ensured that the patient is pain-free should the use of sedatives be contemplated.

Therefore, in the comfort management of the critically ill paediatric patient, identifying and managing pain comprise the first step. This symptom can be appraised in the paediatric population by means of several self-assessment scales in communicative patients, such as the numerical or visual analogue scale, as well as the behavioural FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability), or the Behaviour Pain Scale in non-communicative patients.12

As far as sedation is concerned, the SECIP defines it as “decreased awareness of the environment.” It also defines different degrees of sedation: conscious sedation, when the patient’s consciousness is mildly depressed and the patient is therefore reactive to stimuli, and deep sedation or hypnosis, when there is a greater depression of consciousness, with loss of protective airway reflexes.3 Even so, it is important to note that some authors point out that sedation of the critical patient being treated in the ICU includes analgesia, delirium, humanization, early mobilization, and promoting sleep at night.13 consequently, both analgesia and sedation become useful tools in maintaining an optimal and safe level of comfort in the critically ill child.

Unlike pain, whose assessment and instruments are systematized, in the case of the objective evaluation of the degree of sedation in the critically ill patient, although the use of validated scales is recommended,14 this determination in the paediatric field is complex because there is no gold standard instrument that enables us to quantify the degree of sedation and, subsequently, of agitation.15 However, the Spanish Society of Intensive, Critical, and Coronary Care Medicine (SEMCYUC), the Society of Critical Care (SCC),a and the Spanish Society of Paediatric Intensive Care (SECIP) calls for this determination and on the use of validated scales during clinical management of the degree of sedation and agitation of the critically ill patient.

Although the degree of sedation is not widely determined in the PICU and the various scales have not been adapted and validated in the Spanish setting, there are instruments such as the Motor Activity Assessment Scale (MAAS), the Sedation-Agitation Scale (SAS), and the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS), which make it possible to gauge it, particularly in adult patients.8 The most widely used instruments are the Ramsay and COMFORT scales, although their main limitations are that they have not been validated in paediatrics; that they have not been proven to be useful in patients with muscle relaxation, and that they have not been tested much in children.15 Currently, the SECIP recommends the use of the COMFORT Behaviour Scale,16 recently validated for the Spanish population, which makes it possible to quantify the degree of discomfort of the critically ill paediatric patient, both conscious and sedated, from a psychological perspective, defined as negative behaviours on the organism and associated with fear, anxiety, and pain in critically ill children.17 In addition, the Hospital Niño Jesús procedural sedation scale is available for monitoring sedation in invasive procedures under deep sedation in paediatrics.18

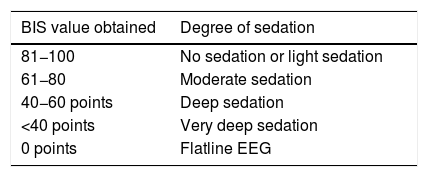

At the same time, it is important to emphasize that several studies have addressed the efficacy of non-invasive monitoring by determining the BIS (Fig. 1), in the assessment of the degree of sedation, albeit with disparate results, but deemed acceptable, especially in the paralyzed or muscularly relaxed patient19–25 and in the palliative patient.26 This index has been validated in a population of >1 month old, although some authors advocate its usefulness in patients older than 6 months,27–30 and it measures the degree of hypnosis in the critically ill paediatric patient by estimating the level of electrical activity by examining electroencephalographic wave frequencies. The main limitation of the BIS is that there is no clear evidence as to which values are associated with better results in the critically ill paediatric patient and that the sensor can sometimes injure the patient’s skin. Even so, its use is widespread in PICUs and often guides the sedation guidelines according to the values obtained (Table 1).

Relationship between the Bispectral Index Sensor (BIS) value and the degree of sedation.34

| BIS value obtained | Degree of sedation |

|---|---|

| 81−100 | No sedation or light sedation |

| 61−80 | Moderate sedation |

| 40−60 points | Deep sedation |

| <40 points | Very deep sedation |

| 0 points | Flatline EEG |

As pointed out by Alcántara et al. in their research, staggered management of the critical patient, focusing first on analgesia and, once controlled, on the degree of sedation, helps to avoid adverse events and situations of difficult sedation.12 Therefore, adequate assessment and management of the degree of pain should be promoted to avoid situations of underdiagnosis.12,31 The same applies to the degree of sedation, in which inadequate monitoring can lead to excessive use of drugs, with the consequent haemodynamic instability, delay in weaning off of the ventilator and increased morbidity and mortality, or the opposite, which could lead to patient desynchrony with the ventilator and even cases of accidental extubation.15

In the specific field of paediatrics, Mahajan et al. propose that the neurobiological development of the patient, as well as his or her anatomical structures and functional abilities, confer a high susceptibility to pain and the consequent hemodynamic, immune, hormonal and metabolic stress responses, higher than those of the adult patient.32 At the same time, the immaturity of the different organs and systems of the paediatric patient means that they respond differently to a pathological process, so they should never be treated as miniature adults.33 For this reason, variables such as age, sex, whether or not they present a chronic disease and the reason for admission to the PICU can have an impact on the pharmacological needs of these critical patients. The justification for the present study derives from the importance of routinely assessing and ensuring an adequate level of analgesia and sedation throughout the comprehensive care of the paediatric critical patient, individualizing drugs and doses, and from the fact that no research has been found that determines the interrelation between degree of sedation and sociodemographic and clinical variables of the patient.

This article details part of the results obtained from a larger multicentre investigation, whose objectives were: (1) to determine the levels of sedation in the paediatric critical patient using the BIS sensor and (2) to analyse the relationship between the degree of sedation and the patient’s sociodemographic and clinical variables.

Material and methodAn observational, analytical, cross-sectional, multicentre, observational study was carried out between May 2018 and January 2020 at 5 Spanish PICUs.

Taking into account a non-probabilistic and consecutive sampling technique, patients from 7 days (minors were excluded because they are admitted to neonatal critical areas) to 18 years of age were included according to the criteria below.

Inclusion criteria:

- 1

Acceptance and signing of the informed consent form.

- 2

Administration of sedatives and analgesics via continuous infusion pump for at least 24 h.

- 3

Monitoring of the degree of sedation using the BIS.

Exclusion criteria:

- 1

Paediatric patients with a skin lesion on the forehead.

- 2

Paediatric patients who were terminal at the time of study.

- 3

Significant language barrier that hinders communication with the family.

The sociodemographic and clinical variables selected were patient age (in years), sex, whether or not the patient was suffering from a chronic disease, the reason for admission to the PICUs analysed, work shift during which the degree of sedation was assessed (morning 8:00−20:00 or night 20:01−7:59), type and amount of sedative, and analgesic drugs prescribed and the length of stay in the PICU (in days).

The degree of sedation was determined by placing a BIS on the patient’s forehead (Fig. 1). To find differences between scores, they were categorized as follows: no sedation (score of 81−100); moderate sedation (scores of 61−80); deep (scores of 40−60); very deep (score ≤40) and electroencephalographic suppression (score of 0).34–36

Data collection processFirst, an ad hoc data collection notebook was created that included informed consent, sociodemographic and clinical variables, and data collection grids. This document was validated by the entire research team of the 5 collaborating centres. The entire collaborating team was then trained telematically, detailing the research objectives, the instruments, and the data collection procedure. When a patient satisfied the aforementioned inclusion criteria and the family gave their free and voluntary consent to participate in the study, the patient’s sociodemographic and clinical data were recorded in the ad hoc document. Determinations of sedation by recording the BIS value that appeared on the monitor were performed once per shift (day and night) to determine whether the work dynamics between the day and night shifts impacted the degree of sedation during the first 24 h of the patient’s inclusion in the study. These values were deemed valid if they obtained a signal quality index >95.

Statistical analysisAll the data from the study were stored in a database created with the IBM® SPSS v.23 statistical software package.

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median, or quartiles) were used to represent the results derived from numerical variables, while categorical variables were expressed as frequency tables with percentages.

Spearman’s correlation was calculated to determine if there was a relationship between 2 numerical variables and Goodman’s and Kruskal’s γ correlation to establish such a relationship between a numerical and an ordinal variable. To establish comparisons of means between a numerical variable and a categorical variable, the Student’s t-test, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, and the Mann–Whitney U test were used, according to their distribution. Pearson’s χ2 test was used to calculate the relationship between 2 categorical variables.

A 95% confidence interval was assumed throughout and data were considered statistically significant if p ≤ 0.001.

Ethical considerationsPrior to the research, the corresponding approval was obtained from the Ethics and Clinical Research Committee of all collaborating centres. During the planning and execution of the research, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2009) and those of the Belmont Report were taken into account, as well as the precepts set forth in Organic Law 1/1996 on the legal protection of minors and in the basic Law 41/2002 regulating patient autonomy and the rights and obligations regarding clinical information and documentation.

Participation in this study was at all times voluntary. Each participating family member was informed verbally and in writing and was also asked for written informed consent. The patient and family member’s anonymity was ensured during the handling of the information, thereby preserving the issues raised in the Spanish Personal Data Protection Act LORTAD (Organic Law 15/1999 of 13 December).

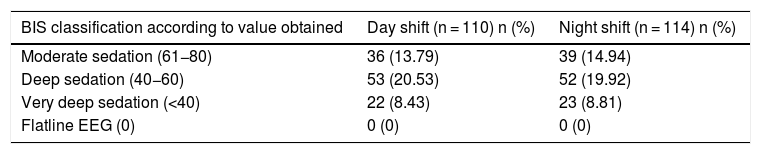

ResultsA total of 261 patients were included in the study, of which 53.64% were male, with a median age of 1.61 years (0.35–6.55); 70.11% (n = 183) of the sample was being administered analgesia and sedation and had BIS sensor monitoring, compared to 29.89% (n = 78) who were not. Midazolam (40.23%; n = 105), methadone (36.40%; n = 95) and fentanyl (16.09%; n = 42) were the most commonly used sedative and analgesic drugs. Median overall BIS scores were 51.24 ± 14.96 during the day shift and 50.75 ± 15.55 during the night shift. When classifying the scores, establishing degrees of sedation and dividing them by work shifts, the largest group of patients were determined to be in deep sedation (20.31%; n = 53 during the day shift versus 19.92%; n = 52 during the night shift) (Table 2). The median PICU stay was 5 days (2–12).

Degree of sedation according to the Bispectral Index Sensor classification and work shift (n = 183).

| BIS classification according to value obtained | Day shift (n = 110) n (%) | Night shift (n = 114) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Moderate sedation (61−80) | 36 (13.79) | 39 (14.94) |

| Deep sedation (40−60) | 53 (20.53) | 52 (19.92) |

| Very deep sedation (<40) | 22 (8.43) | 23 (8.81) |

| Flatline EEG (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

BIS: Bispectral Index Sensor.

When analysing the data obtained by sex, mean BIS scores during the day shift were 50.64 ± 15.23 in boys versus 51.98 ± 14.90 points in girls. As for night shift, values recorded were 50.14 ± 16.30 in boys and 51.62 ± 14.87 in girls. When comparing mean sedation scores and relating them to the sex variable, no statistical significance was obtained with respect to the day time (Student’s t: −046; p = .64) or the night time (Student’s t: −0.51; p = .60). When classifying the mean scores into degrees of sedation, 41.8% (n = 23) of the girls and 52.7% (n = 29) of boys were seen to be under deep sedation during the day shift (n = 110) versus 44.8% (n = 26) of boys and 46.4% (n = 26) of girls during the night shift (n = 114). Likewise, there was no statistical significance between the degree of sedation and patient sex during the morning shift (χ2 1.6; p = .42) or during the night shift (χ2 .38; p = .82).

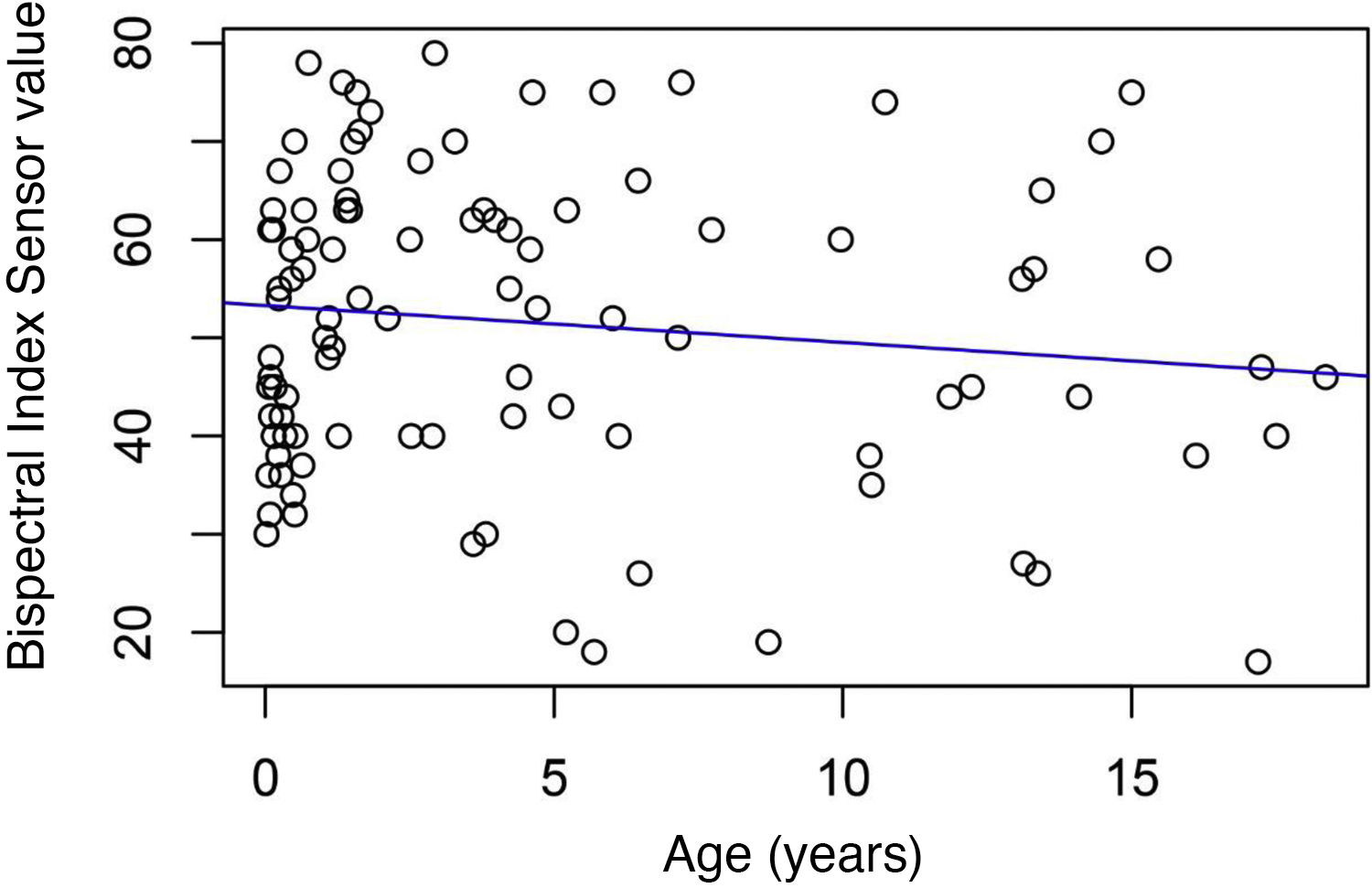

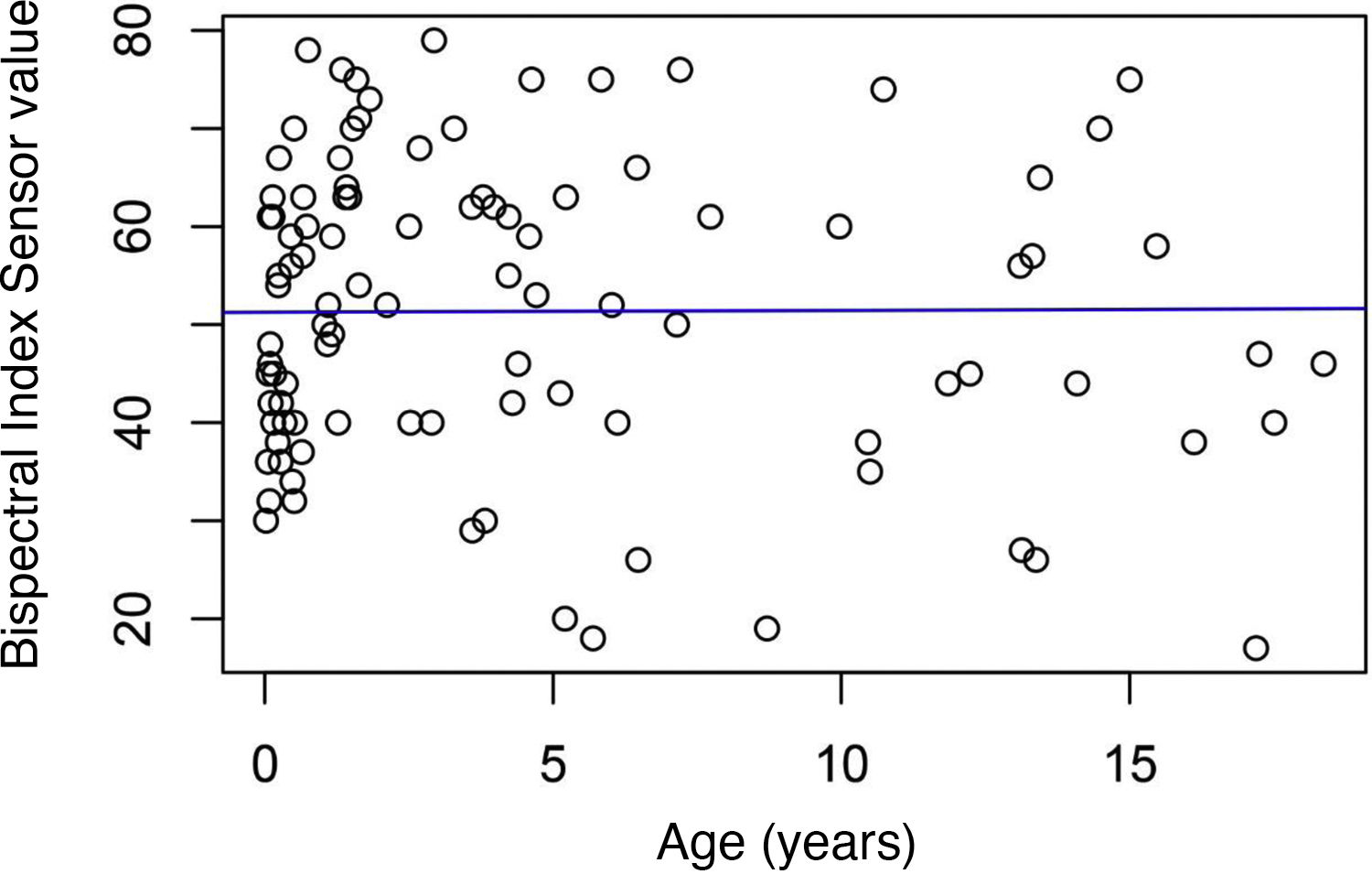

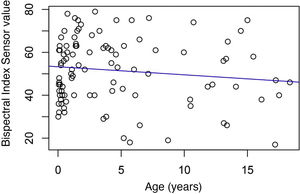

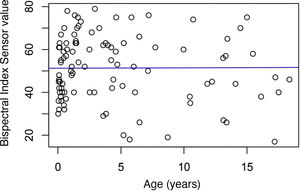

The relationship between the global degree of sedation and the age of the paediatric critically-ill patient was calculated and no relationship or statistical significance was found for the day shift values (Rho: .016; p = .87) or the night shift values (Rho: 0.089; p = .37) (Figs. 2 and 3).

Almost one third (32.95%; n = 86) of the study sample had a chronic disease, with congenital heart disease being the most prevalent (16.9%; n = 42). Of them, 48.4% (n = 15) of the day shift were being administered analgesia and sedation versus 46.9% (n = 15) of those on the night shift. When comparing the mean BIS recorded and the variable of whether or not the patient had a chronic disease, no statistical significance was found (Student’s t: −.27; p = .78 during the day shift; Student’s t: .19; p = .83 during the night shift). Similarly, no statistical significance found when comparing the degrees of sedation and whether or not the patient had chronic disease (χ2 .33; p = .84 during the day shift; χ2 .19; p = .84 during the night shift).

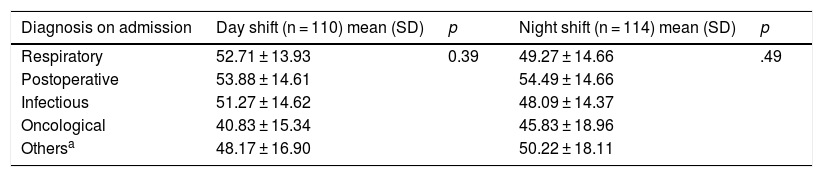

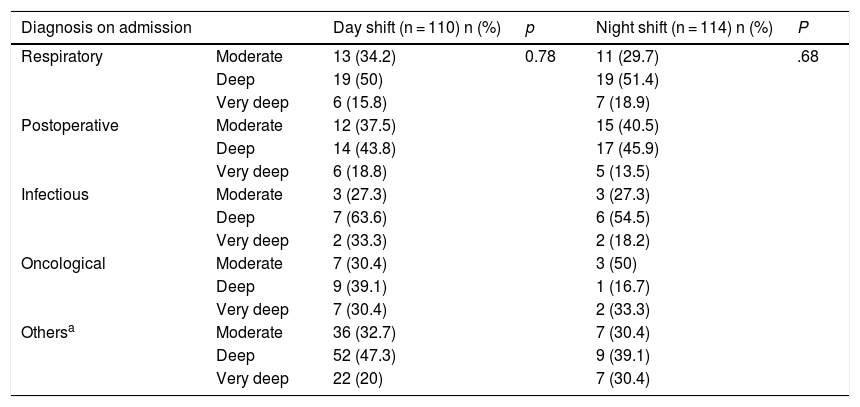

The relationship was established between the clinical diagnosis that led to admission into the PICU and the degrees of sedation. In this regard, a respiratory diagnosis was the one leading to the highest degree of sedation during the day shift (deep sedation in 50%; n = 19, and moderate in 34.2%; n = 13). As for the night shift, 51.4% (n = 19) of respiratory patients were in deep sedation versus 40.5% (n = 15) of post-surgical patients, who were in moderate sedation. No statistical significance was detected when comparing the mean BIS and the disease motivating admission into PICUs during the day shift (Kruskal–Wallis test: 4.10; p = .39) or during the night shift (Kruskal–Wallis test: 3.38; p = .49). Upon comparison of the degree of sedation and the disease leading to admission, no statistically significant data were found during the day shift (χ2 4.75; p = .78) or during the night shift (χ2 5.69; p = .68) (Tables 3 and 4).

Mean scores of the Bispectral Index Sensor obtained, work shift, and diagnosis on admission.

| Diagnosis on admission | Day shift (n = 110) mean (SD) | p | Night shift (n = 114) mean (SD) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | 52.71 ± 13.93 | 0.39 | 49.27 ± 14.66 | .49 |

| Postoperative | 53.88 ± 14.61 | 54.49 ± 14.66 | ||

| Infectious | 51.27 ± 14.62 | 48.09 ± 14.37 | ||

| Oncological | 40.83 ± 15.34 | 45.83 ± 18.96 | ||

| Othersa | 48.17 ± 16.90 | 50.22 ± 18.11 |

SD: standard deviation.

Degree of sedation, work shift, and diagnosis on admission.

| Diagnosis on admission | Day shift (n = 110) n (%) | p | Night shift (n = 114) n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | Moderate | 13 (34.2) | 0.78 | 11 (29.7) | .68 |

| Deep | 19 (50) | 19 (51.4) | |||

| Very deep | 6 (15.8) | 7 (18.9) | |||

| Postoperative | Moderate | 12 (37.5) | 15 (40.5) | ||

| Deep | 14 (43.8) | 17 (45.9) | |||

| Very deep | 6 (18.8) | 5 (13.5) | |||

| Infectious | Moderate | 3 (27.3) | 3 (27.3) | ||

| Deep | 7 (63.6) | 6 (54.5) | |||

| Very deep | 2 (33.3) | 2 (18.2) | |||

| Oncological | Moderate | 7 (30.4) | 3 (50) | ||

| Deep | 9 (39.1) | 1 (16.7) | |||

| Very deep | 7 (30.4) | 2 (33.3) | |||

| Othersa | Moderate | 36 (32.7) | 7 (30.4) | ||

| Deep | 52 (47.3) | 9 (39.1) | |||

| Very deep | 22 (20) | 7 (30.4) |

There was no case of flatline EEG.

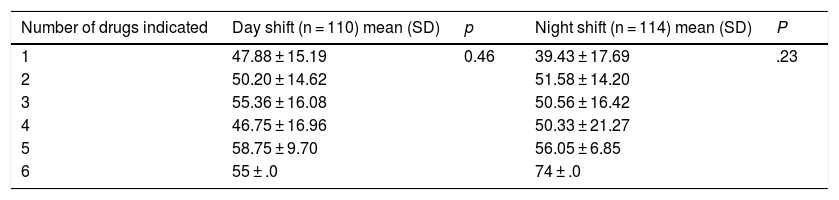

We examined whether the number of analgesia and sedation drugs affected the degree of sedation of the paediatric critically-ill patient and similar means were attained in all groups, without statistical significance (Table 5).

Mean scores of the Bispectral Index Sensor obtained, work shift, and number of drugs administered.

| Number of drugs indicated | Day shift (n = 110) mean (SD) | p | Night shift (n = 114) mean (SD) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 47.88 ± 15.19 | 0.46 | 39.43 ± 17.69 | .23 |

| 2 | 50.20 ± 14.62 | 51.58 ± 14.20 | ||

| 3 | 55.36 ± 16.08 | 50.56 ± 16.42 | ||

| 4 | 46.75 ± 16.96 | 50.33 ± 21.27 | ||

| 5 | 58.75 ± 9.70 | 56.05 ± 6.85 | ||

| 6 | 55 ± .0 | 74 ± .0 |

SD: standard deviation.

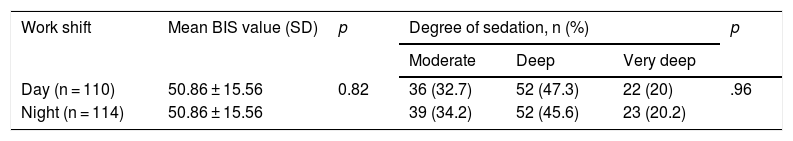

The mean BIS scores and the degrees of sedation of the paediatric critical patient were probed globally and were related to the work shift, albeit failing to achieve statistical significance when comparing means (Student’s t: .22; p = .82) or the degrees of sedation (χ2 .07; p = .96) (Table 6).

Relationship between the Bispectral Index Sensor, degree of sedation, and work shift.

| Work shift | Mean BIS value (SD) | p | Degree of sedation, n (%) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate | Deep | Very deep | ||||

| Day (n = 110) | 50.86 ± 15.56 | 0.82 | 36 (32.7) | 52 (47.3) | 22 (20) | .96 |

| Night (n = 114) | 50.86 ± 15.56 | 39 (34.2) | 52 (45.6) | 23 (20.2) | ||

SD: standard deviation.

Finally, no statistically significant relationship was observed between the hours of stay in the PICUs analysed and the degree of sedation of the paediatric critical patient (Kruskal–Wallis test: 2.62; p = .27).

DiscussionThroughout the stay of a paediatric patient in a PICU, correct monitoring and pain management must be guaranteed through the use of scales adapted to the age of the patient and the administration of analgesics. Once this therapeutic step is controlled, adequate levels of sedation must be ensured in patients who require it. At the same time, the fact that pharmacological needs may vary, given the anatomical and physiological characteristics of this vulnerable group of patients, must be taken into account, incrementing the need to control and manage them even greater.

Although some research suggests that the BIS is a method of monitoring currently under debate,37 particularly in the paediatric population, the lack of scales with psychometric studies of validity and reliability with which to assess the degree of sedation makes their use somewhat widespread in PICUs. Research by Berkenbosch et al. demonstrated the usefulness of the BIS to evaluate sedation in PICU,38 and research by Tschiedel et al.37 indicates that monitoring with the BIS did not affect the doses of the sedatives administered, post-anaesthesia recovery time, or the presence of complications. Therefore, the BIS is a useful tool in PICUs; it is recommended by some authors during procedures requiring deep sedation,39,40 and was the main method of assessment in the PICUs analysed.

The results of this study indicate that the sedation situations are adequate, as per the parameters established by the BIS, with BIS values of 51.24 ± 14.96 during the morning shift and 50.75 ± 15.55 during the night shift. These data are similar to those of another study, which ascertained values of 52 (0–98),29 and somewhat lower compared to other studies that obtained overall scores of 5937 or 62 ± 42.6.41

Some investigations have established a correlation between the BIS value and that obtained after assessing the degree of sedation of the critically-ill paediatric patient using the COMFORT Scale.29,41 For this reason, the recently validated COMFORT Behaviour Scale Spanish version17 might also be a useful tool with which to monitor sedation management in critically-ill paediatric patients, as also recommended by the SECIP. Nevertheless, as it is a recently validated instrument, further clinical research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Although no statistical significance was observed in the present study between the degree of sedation and sociodemographic and clinical variables of the critically-ill paediatric patient, the results obtained could not be compared due to the lack of similar research. Even so, there is a recent study in which the degree of discomfort of the critical paediatric patient and its relationship with sociodemographic and clinical variables was determined in a single-centre study. In this study, a relationship was observed between degree of discomfort and age, stay in PICU, and analgesia-sedation.42

The main limitation of the present investigation lies in the fact that we do not have valid and reliable gold standard instruments with which to compare the degrees of sedation in critical, paediatric patients and thus, avoid the possible limitations of the BIS. This limitation has been addressed by only recording BIS values when a signal quality index above 95 was obtained. Moreover, no scientific literature has been found to determine which sociodemographic and clinical variables have the greatest influence on the degree of sedation, so that another limitation of the research is established by not being able to compare the results obtained.

Despite the inherent limitations of the BIS sensor, including low sensitivity in determining the degree of sedation if ketamine is being administered to the patient or interference caused by neurological or neurocritical illnesses, existing studies and the one presented here reveal that the BIS is a useful instrument for monitoring the degree of sedation in the critically-ill paediatric patient. Further research is needed to ascertain which patient-related variables have more weight in the degree of analgesia and to clinically test the efficacy of scales such as the CBS-ES in determining the degree of discomfort related to adequate or inadequate analgesia or sedation. Monitoring the degree of analgesia throughout the comprehensive care of the paediatric critical patient improves safety and quality of care because it considerably reduces situations of under-diagnosis of pain and under- or over-sedation, with a direct impact on the development of adverse events in a patient as vulnerable as the paediatric critical patient.

FundingThis research has not been funded by any organisation or private company.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank the entire research team for their enthusiasm and help throughout the whole data collection process and the paediatric patients and their families who agreed to participate in the study.

Please cite this article as: Bosch-Alcaraz A, Alcolea-Monge S, Fernández Lorenzo R, Luna-Castaño P, Belda-Hofheinz S, Falcó Pegueroles A, et al. Grado de sedación del paciente crítico pediátrico y variables sociodemográficas y clínicas correlacionadas. Estudio multicéntrico COSAIP. Enferm Intensiva. 2021;32:189–197.