Validation of the informal care gains scale available in Spanish to extend it to a version for caregivers of patients with multimorbidity at home.

MethodPsychometric validation study in family caregivers of people with multimorbidity in home care. Content validation was carried out using a panel of experts and the Delphi technique and subsequent empirical validation in a sample of family caregivers of patients with multimorbidity in home care.

ResultsPHASE I: 3 of the 10 items were modified to specify the study population. PHASE II: A total of 227 subjects, with a median age of 84 years in patients and 59 years in family caregivers. 78.9% of the caregivers were women. The reliability analysis offered McDonald's omega values of .82, with an average inter-item correlation of .41. The test-retest reliability offered a value of .95. The bifactor structure obtained a good fit: RMSEA of .08 (90% CI .06–.11), TLI .88, explaining 40.6% of the variance. The instrument showed discriminative capacity between caregivers based on overload (p < .001).

ConclusionsThe GAIN scale is a valid and reliable instrument for measuring the gains of family caregivers of people with multimorbidity in home care. It is easy to use and allows you to understand what factors to enhance in caregivers to preserve their resilience during the process.

Validación de la escala de ganancias GAIN en el cuidado informal disponible en español, para extenderla a una versión para cuidadores de pacientes con multimorbilidad en el domicilio.

MétodoEstudio de validación psicométrico en cuidadores familiares de personas con multimorbilidad en atención domiciliaria. Se procedió a la validación de contenido mediante panel de expertos y técnica Delphi y posterior validación empírica en una muestra de cuidadores familiares de pacientes con multimorbilidad en atención domiciliaria.

ResultadosFASE I Se modificaron 3 de los 10 ítems para especificar la población de estudio. FASE II Un total de 227 sujetos, con una edad mediana de 84 años en pacientes y 59 años en cuidadores familiares. El 78,9% de los cuidadores eran mujeres. El análisis de la fiabilidad ofreció valores de omega de McDonald de 0,82, con una correlación media inter-ítem de 0,41. La fiabilidad test-retest ofreció un valor de 0,95. La estructura bifactorial obtuvo un buen ajuste: RMSEA de 0,08 (IC90% 0,06 a 0,11), TLI 0,88, explicando un 40,6% de la varianza. El instrumento mostró capacidad discriminativa entre cuidadores en función de la sobrecarga (p < 0,001).

ConclusionesLa escala GAIN es un instrumento válido y fiable para la medición de las ganancias de los cuidadores familiares de personas con multimorbilidad en atención domiciliaria. Es de fácil uso y permite comprender qué factores potenciar en los cuidadores para preservar su resiliencia durante el proceso.

What is known?

GAIN (Gain in Alzheimer Care Instrument) is an instrument that focuses on positive health, which has been little studied to date. However, there is no validated version in Spain applicable to people with multimorbidity and high dependency, who will represent the majority of the future demand for home care.

What does it contribute?

A valid and reliable instrument for measuring gain in informal caregivers of people with multimorbidity and dependency who receive care at home.

The ageing of the population has put multimorbidity at the centre of health policy priorities,1 with increased demand for support care that falls mainly on informal care provided by women, who face increasing difficulties due to their work commitments,2 in many cases forcing them to combine work and care roles, or to give up careers.3

Caregiver burden can affect health at a psychological level, such as anxiety and depression, use of psychotropic drugs,4,5 or complicated grief,6 and at a physical level, such as an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.7 Paradoxically, some studies show a lower mortality in family caregivers, suggesting that their caregiving may have potential positive aspects that could have a protective effect.8 Salutogenic models consider that, if a person has health assets that allow them to perceive their life as coherent, structured, and understandable, they will have more opportunities to face life's challenges.4

Assessments of the health situation of caregivers have mainly focused on caregiver burden.9,10 There is a 10-item instrument, the Gain in Alzheimer care Instrument (GAIN),11 which focuses on positive health and has been validated in Spain.12 This instrument explores the gains that caregivers experience in terms of affective, relational, or personal growth. In its first Spanish version it showed good reliability with a unidimensional factor structure.12 A systematic review of these instruments found that the GAIN may be most appropriate for caregivers of institutionalised older people.13

However, the existing version has limitations. It is validated for caregivers of people with dementia, but there is no version applicable to people with multimorbidity, who currently account for the majority of home care needs. There is a version validated in Spain, obtained after exploratory factor analysis, with a unidimensional structure. Subsequently, this factor structure was reproduced with confirmatory methods in a sample of caregivers of people with dementia, although with a reduced sample and again only in this specific population.14

The aim of this study is to validate the scale available in Spanish and to extend it to a version for caregivers of patients with multimorbidity at home.

MethodPhase IAdaptation of the content of the Fabà and Villar questionnaire12 to female caregivers of people with multimorbidity and its validation by a panel of experts and Delphi technique. This questionnaire consists of 10 items, covering the dimensions of personal growth, gains in relationships, and higher-level gains. The items have a common heading "Providing care to my relative has… ". And the possible answers are "strongly disagree ", "somewhat disagree", "neither agree nor disagree", "somewhat agree", and "strongly agree". Scores can range from 0 (no gain) to 40 (experiencing greater gain).11,12

The selection criteria for the panellists included extensive clinical experience (more than 10 years) in home care and family caregivers, with an advanced practice profile and ongoing training in home care (>50 h per year) (Appendix B Annex 1).

They were asked to make modifications to adapt it to the study population, and the relevance of the items. The data was collected with LimeSurvey 5.3.

Phase IIThe survey was empirically evaluated to determine its reliability, construct validity, and discriminant validity by means of a multicentre analytical cross-sectional study. A minimum sample size of 144 subjects was estimated as necessary for the reliability analysis for an alpha of .05, a beta of .9 for an instrument of 10 items and with an H0 of .7 and H1 of .8.15 For a confirmatory analysis with an alpha of .05, a power of .9, in a two-factor solution of 10 observed variables, 182 subjects were needed.16 This sample was overestimated by 20% to cover possible sample losses (n = 220).

Family caregivers of people with multimorbidity, who had performed this role for at least 6 months in the Primary Care District of Malaga, were included between May 2018 and April 2021. Together with the socio-demographic data of patients and caregivers, the CSI (caregiver strain index) was assessed, as well as variables related to aspects of their work as family caregivers: the number of times they performed certain tasks during care, the time they had been caring, the perceived commitment to family care. Information was also collected on the caregiver's level of education, occupation, and whether they were taking antidepressants and/or anxiolytics (Appendix B Annex 2).

Data were collected by telephone or in person, at the health centre or at home. Recruitment was carried out consecutively by family nurses according to daily appointment lists for their respective care quotas. A sub-sample of 30 subjects was also collected, to whom the instrument was administered twice, repeatedly, at 15-day intervals, to assess test-retest reliability.

AnalysisPhase IThe content validity index was calculated by item and overall, according to Lynn et al., using a Likert scale from 1 to 4, adjusted for the probability of agreement by chance, assuming a minimum threshold of .8 and calculating the modified k17,18 (Appendix B Annex 3).

Phase IIDescriptive statistics were obtained for the variables, with measures of central tendency and dispersion or percentages, and normality assessment using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Bivariate analysis was performed using non-parametric tests due to the general lack of normality: Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests for differences in means (although ANOVA was also performed using Brown-Forsythe test and Games-Howell post-hoc comparisons as robust measures). The χ² test was used for qualitative variables. Linear regression models were used for the relationship between GAIN scores as the dependent variable and time spent in the role of caregiver, or age of caregiver or patient, or time spent per week caregiving as independent variables.

For empirical validation, the ceiling-floor effect was first evaluated using endorsement frequency. Internal consistency was calculated using McDonald's omega, which does not depend on the normality of the scores. Inter-item and item-total correlations were also analysed. Test-retest reliability was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and the Bland-Altman test. For construct validity, an exploratory factor analysis was first carried out, using the principal axis factor extraction method, oblique rotations (Oblimin), and non-linear approximation using polychoric correlations. The principal axis factor extraction method was used following the recommendation of Lloret et al. to employ ordinary least squares methods for non-linear approximations.19 Previously, Bartlett's test of sphericity and KMO test were carried out. An attempt was then made to reproduce the unifactorial model validated in our country with confirmatory methods, and then with a bifactorial model, in the absence of fit of the former. Next, a structural equation analysis was performed on a bifactorial approximation. The following were used as indices of adjustment: penalty function (χ2/df)>3; RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) <.08 and its 90% confidence interval; the CFI (Comparative Fit Index) and the TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index), with minimum values for a good fit ≥.90.

All analyses were performed with Jamovi 2.4.11, JASP .18.3 and with the Soper sample size calculator.20

Ethical aspectsThe study was authorised by the Provincial Research Ethics Committee of Malaga, with the number 1091-M1-16. All participants were asked for informed consent. The data was handled anonymously and in compliance with all the precepts of current legislation (Appendix B Annexes 4 and 5).

ResultsPhase IThe panel consisted of 16 nurse case managers (75% female) with a mean age of 52.5 years (IQR 4) and a mean experience of 29.5 years (IQR 4). All 100% had updated their training in the last year, and 12.5% had a doctorate (Appendix B Annex 1).

After the consensus phase of the Fabà and Villar questionnaire, three items were modified (4, 5, and 7), changing the word ”dementia” to ”dependency”. The overall CVI obtained was .85, with a probability of random agreement between .0001 and .009 (Appendix B Annex 6). The item with the lowest median in terms of relevance was item 6 (median 3; IQR 2).

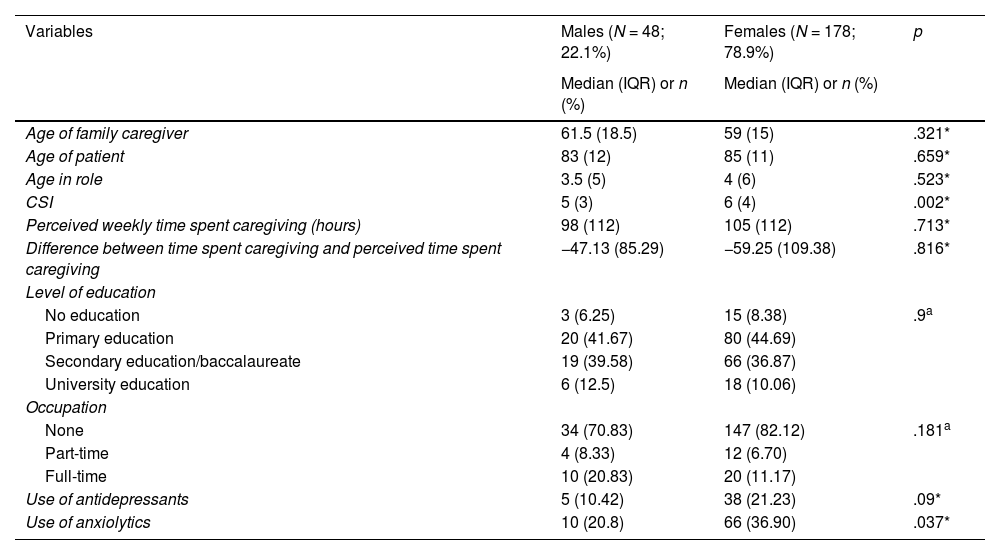

In the empirical phase, the final sample consisted of 227 subjects with a median age of 84 (IQR 12) years for patients and 59 (IQR 17.5) years for caregivers. Of the caregivers, 78.9% (n = 179) were women and had been caregiving for a median of 4 (IQR 5) years. The women had higher levels of overload than the men and higher levels of anxiolytic use, with no significant differences by sex in the other variables assessed. The detailed characteristics of the sample and the differences by sex are shown in Table 1. There was a significant difference between the perceived weekly time (median 98 h; IQR 112) and the time derived from real tasks performed (median 31.2 h; IQR 19.2) (W Wilcoxon: 22.75; p < .001).

Characteristics of the sample by sex.

| Variables | Males (N = 48; 22.1%) | Females (N = 178; 78.9%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) or n (%) | Median (IQR) or n (%) | ||

| Age of family caregiver | 61.5 (18.5) | 59 (15) | .321* |

| Age of patient | 83 (12) | 85 (11) | .659* |

| Age in role | 3.5 (5) | 4 (6) | .523* |

| CSI | 5 (3) | 6 (4) | .002* |

| Perceived weekly time spent caregiving (hours) | 98 (112) | 105 (112) | .713* |

| Difference between time spent caregiving and perceived time spent caregiving | −47.13 (85.29) | −59.25 (109.38) | .816* |

| Level of education | |||

| No education | 3 (6.25) | 15 (8.38) | .9a |

| Primary education | 20 (41.67) | 80 (44.69) | |

| Secondary education/baccalaureate | 19 (39.58) | 66 (36.87) | |

| University education | 6 (12.5) | 18 (10.06) | |

| Occupation | |||

| None | 34 (70.83) | 147 (82.12) | .181a |

| Part-time | 4 (8.33) | 12 (6.70) | |

| Full-time | 10 (20.83) | 20 (11.17) | |

| Use of antidepressants | 5 (10.42) | 38 (21.23) | .09* |

| Use of anxiolytics | 10 (20.8) | 66 (36.90) | .037* |

The median GAIN score obtained was 36 (IQR 6). The endorsement frequencies did not show the presence of a ceiling/floor effect, except for item 4, where a frequency of 87.2% was obtained at level 4.

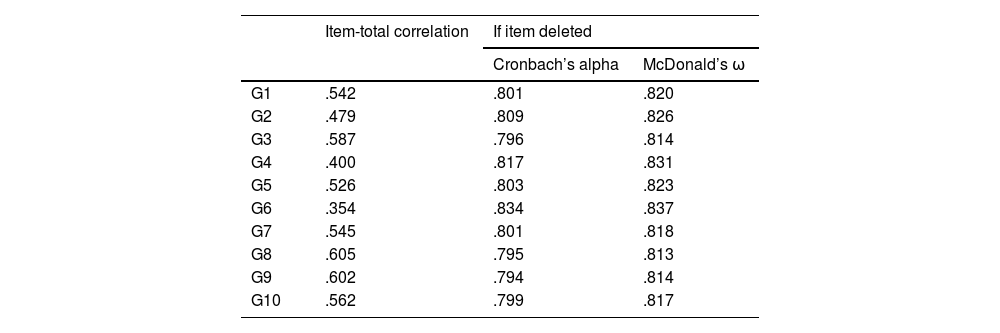

Reliability analysis yielded McDonald’s omega values of .82 (95% CI .79–.86) and Cronbach's alpha of .82 (95% CI .78–.85), with a mean inter-item correlation of .41. Item 6 had the lowest item-test correlation (.35) (Table 2). In the two-factor model, factor 1 obtained a McDonald’s omega of .75 (95% CI .70–.80) and factor 2 of .79 (95% CI .75–.84).

Item-total correlation and internal consistency of the instrument.

| Item-total correlation | If item deleted | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s alpha | McDonald’s ω | ||

| G1 | .542 | .801 | .820 |

| G2 | .479 | .809 | .826 |

| G3 | .587 | .796 | .814 |

| G4 | .400 | .817 | .831 |

| G5 | .526 | .803 | .823 |

| G6 | .354 | .834 | .837 |

| G7 | .545 | .801 | .818 |

| G8 | .605 | .795 | .813 |

| G9 | .602 | .794 | .814 |

| G10 | .562 | .799 | .817 |

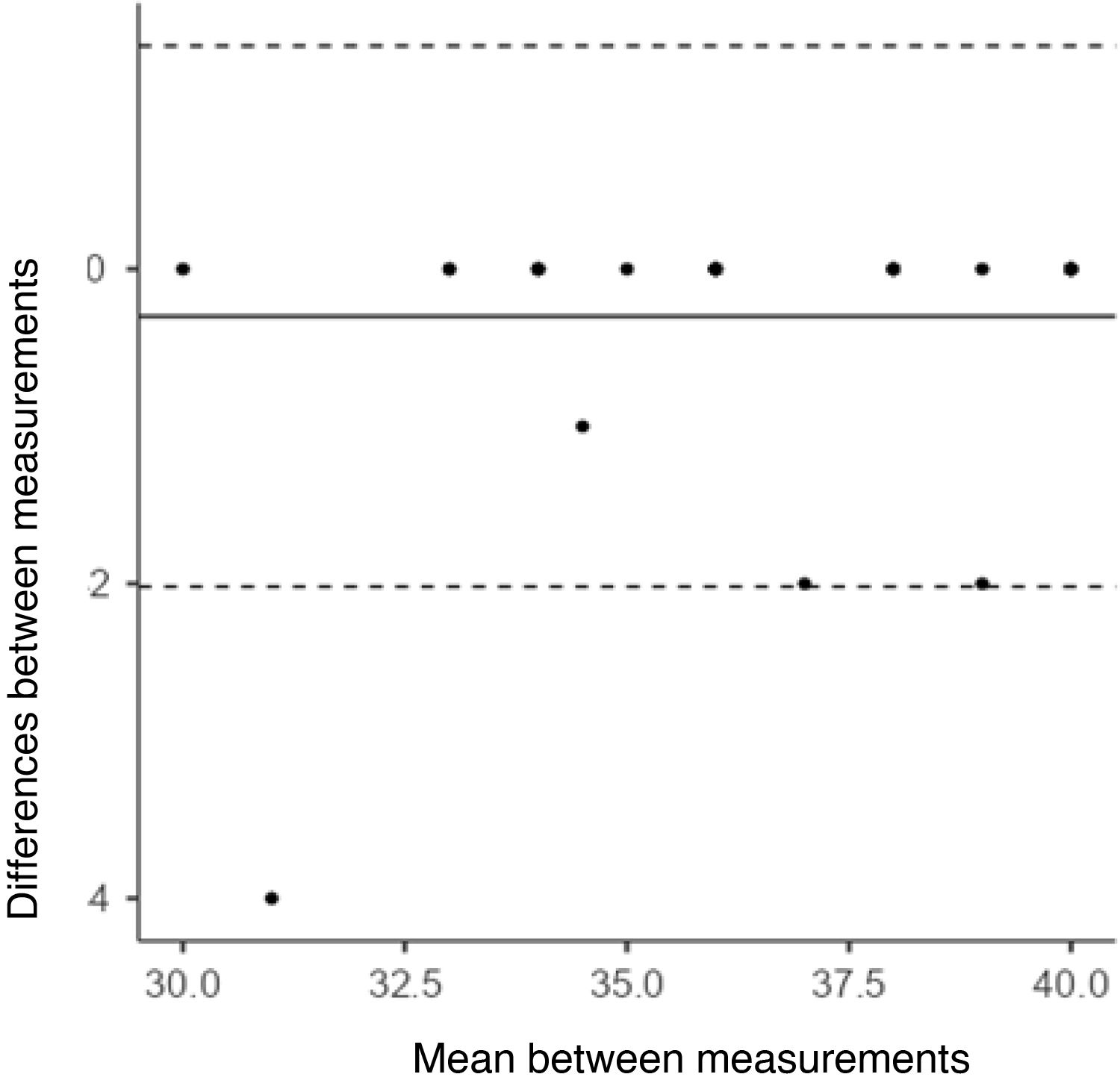

The test-retest reliability provided an ICC of .95 (95% CI .91–.98) and the Bland-Altman plot showed appropriate behaviour of the differences in scores (Fig. 1).

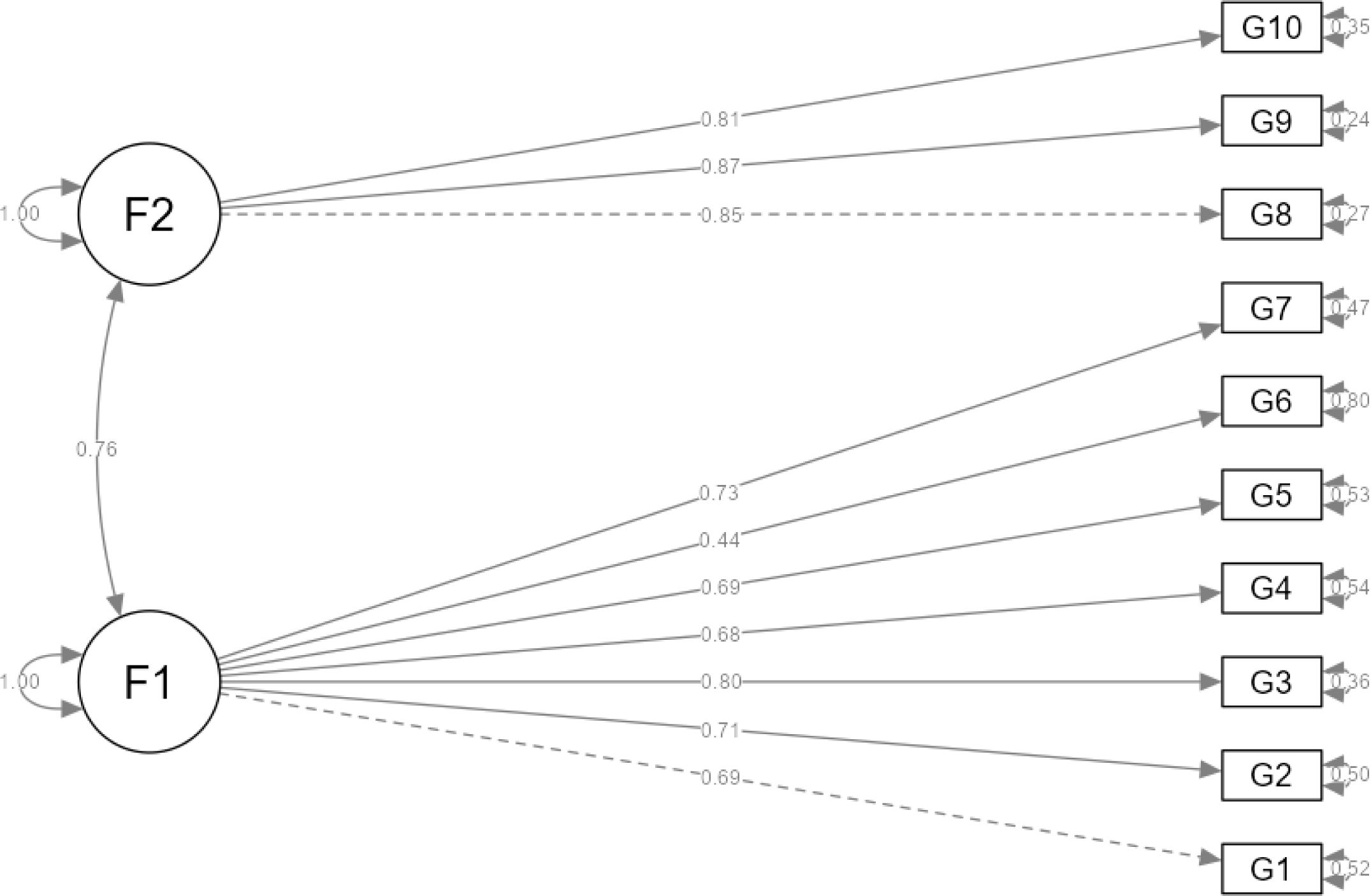

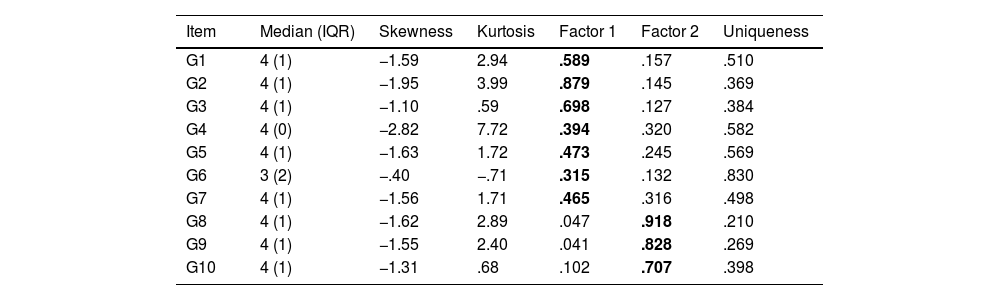

Exploratory factor analysis revealed a two-dimensional structure, with Bartlett's sphericity test (χ2: 668; p < .001) and KMO .831. Items 4 and 6 had the lowest factor loadings. The correlation between the two factors was .66. The total variance explained by these two factors was 40.5% (22% for the first factor and 18.5% for the second), with adjustment values: RMSEA .16 (90% CI .13–.18); TLI .78 (Table 3). Subsequently, a one-dimensional model similar to the Spanish adapted version was evaluated for patients with dementia, first with exploratory and then with confirmatory methods, obtaining worse exploratory fit values than in the bifactor model (RMSEA .18 [90% CI .16–.20]; TLI .71) and the same in the case of confirmatory analysis: RMSEA .11 (90% CI .08–.13), TLI .81, CFI .85; χ2/df of 3.57 (Table 4). Therefore, a confirmatory factor analysis of the two-dimensional structure was performed, with better fit values than the one-dimensional: RMSEA .08 (90% CI .05–.10), TLI .90, CFI .93; χ2/df of 2.45. In addition, a structural equation analysis was performed on this bifactor model, which gave the best fit values: RMSEA .024 (90% CI .00–.56), with a TLI of .99, CFI of .99. χ2/df of 1.84 and correlation matrix residuals <.1 in all cases (Fig. 2).

Distribution of raw scores, skewness, and kurtosis, factor scores, and uniqueness in a two-factor model.

| Item | Median (IQR) | Skewness | Kurtosis | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Uniqueness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 4 (1) | −1.59 | 2.94 | .589 | .157 | .510 |

| G2 | 4 (1) | −1.95 | 3.99 | .879 | .145 | .369 |

| G3 | 4 (1) | −1.10 | .59 | .698 | .127 | .384 |

| G4 | 4 (0) | −2.82 | 7.72 | .394 | .320 | .582 |

| G5 | 4 (1) | −1.63 | 1.72 | .473 | .245 | .569 |

| G6 | 3 (2) | −.40 | −.71 | .315 | .132 | .830 |

| G7 | 4 (1) | −1.56 | 1.71 | .465 | .316 | .498 |

| G8 | 4 (1) | −1.62 | 2.89 | .047 | .918 | .210 |

| G9 | 4 (1) | −1.55 | 2.40 | .041 | .828 | .269 |

| G10 | 4 (1) | −1.31 | .68 | .102 | .707 | .398 |

RMSEA .16 (90% CI .13–.18); TLI .78.

Mardia’s coefficient: 46.02 p < .001; multivariate kurtosis: 191.23 p < .001. The highest scores of the items in the different factors are in bold.

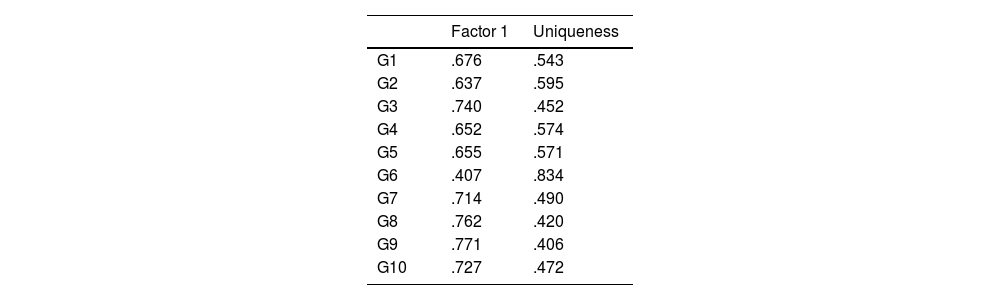

Factor loading and uniqueness in unifactorial model.

| Factor 1 | Uniqueness | |

|---|---|---|

| G1 | .676 | .543 |

| G2 | .637 | .595 |

| G3 | .740 | .452 |

| G4 | .652 | .574 |

| G5 | .655 | .571 |

| G6 | .407 | .834 |

| G7 | .714 | .490 |

| G8 | .762 | .420 |

| G9 | .771 | .406 |

| G10 | .727 | .472 |

RMSEA .18 (90% CI .16–.20); TLI .71.

Mardia’s coefficient: 46.02 p < .001; multivariate kurtosis: 191.23 p < .001.

The discriminatory capacity of the GAIN in relation to the presence of overload was evaluated based on the CSI figures (taking the cut-off point identified by Odriozola et al., 2008). Significantly higher GAIN scores were observed among caregivers without overload than among those with CSI values > 8: caregivers without overload, median GAIN 36 (IQR 4.75) versus median GAIN 33 (IQR 8) in caregivers with overload (U = 3075; p < .001).

The GAIN values according to the educational level of the caregivers did not show significant differences (F (3, 223) = 1.83; p = .141, ɳ2 .024; Kruskal-Wallis: 5.80; p = .122), nor by occupational status (F (2, 224) = .192; p = .825, ɳ2 .002; Kruskal-Wallis: .98; p = .611). In the post-hoc analyses, no differences were found between subgroups in any of the cases.

Caregivers who took antidepressants had significantly lower median GAIN values: 36 (IQR 5.25) versus 35 (IQR 9); (U = 2985; p = .012). In the case of the consumption of anxiolytics this was not the case: 36 (IQR 6) versus 35 (IQR 7.25); (U = 5240; p = .290).

There was no significant association between the time spent in the role of carer and GAIN (β = .1; p = .133), nor with the perceived (β = .03; p = .570) or actual (β=–.04; p = .506) daily dedication, or with the age of the caregiver (β = −.02; p = .707), or that of the patient (β = −.008; p = .902) (Table 1).

DiscussionThe GAIN as a tool for measuring gains was adapted and validated in Spain for caregivers of people with dementia with a one-dimensional factor structure12; it was later found that it could be suitable for family caregivers of institutionalised elderly people.13 With this study we intend to adapt and validate it for caregivers of patients with multimorbidity in the home and to analyse its factor structure.

In our study the median GAIN score obtained high values, somewhat higher than in previous studies.11,12 It is possible that these differences could be due to the different characteristics of the types of patients they care for, as well as the context of care: in the original study11 most patients came from an outpatient dementia centre or an Alzheimer’s association in an Asian country, while in our study all patients were multimorbid, highly dependent, and confined to their homes. Cross-cultural differences have been reported in different dimensions of family care, such as caregiver burden,21–23 and it cannot be ruled out that the positive aspects of care are also affected by cultural values and norms, especially in a context where family care is strongly rooted, as is the case in southern European countries.24

The differences between the real and perceived time spent on family caregiving coincide with previous studies carried out in Spain, in which this distortion of the perception of time spent is attributed to the functional state of the person being cared for, the caregiver burden, age, and living together in the same home, with differences of up to 4 h.25

With regard to the validation process, the original one-dimensional structure of the instrument had worse fit values than the two-dimensional structure. In the first validation in Spain, a two-dimensional structure was initially obtained, but it was considered to be one-dimensional because the correlations and the amount of variance explained by a single factor were similar to those obtained later by confirmatory methods in caregivers of people with dementia.11–14 Further factor invariance studies would be needed to determine whether this behaviour is due to the sample used or whether, on the contrary, this dimensional pattern is maintained in subsequent samples and contexts.

The reliability of the scale, assessed by its internal consistency, was satisfactory and similar to the original GAIN scale and the Spanish adaptation, as was the test-retest reliability.11,12 Item 6 ("Helped to bond my family closer") is the one that received the lowest scores among the participating carers, as well as the one with the lowest discrimination index, similar to the analyses carried out in our setting.12,14 The experts who participated in the content validation phase also considered this item to have the lowest relevance values compared to the others. On the other hand, it has to be taken into account that the organisation and distribution of support in caring for a dependent person often causes tensions among family members, and that the stress of the situation can aggravate pre-existing family conflicts and pose new challenges for family functioning.26,27 Furthermore, with regard to the psychometric behaviour of item 6, previous authors have suggested that it may measure aspects that are not entirely within the individual caregiver's locus of control.11,12 The rest of the items behaved similarly to previous validation studies in Spanish carers of people with dementia, although item 9 ("Helped me grow spiritually") is accepted by a high percentage of caregivers, which is not the case in the aforementioned studies.

Regarding the positive aspects of caregiving as a mediator, Yang et al.28 found that it had a moderating effect on the level of depression in people with dementia. In Spain, García-Castro et al. assessed the possible mediating effect of perceived gains between contextual factors and stressors of caregiving and life satisfaction, as a possible coping strategy, and found that hope had a significant association with perceived gains from caregiving, although no mediating relationship was found between stressors and life satisfaction.29

A caregiver's preparedness to provide care depends on their level of strain and resilience, the latter being an explanatory factor for caregiver's preparedness to provide care, as it is associated with low levels of strain. Resilience is related to several indicators of healthy functioning (quality of life, social support, positive coping) as it buffers the negative effects of strain and distress.4 There may be other gains not included in the GAIN scale that are more representative of caregivers' experiences in our sociocultural context, bearing in mind that the items in the original scale were developed from a small group of interviews in a different cultural setting. Another drawback is that some concepts are too complex for some caregivers, such as ”self-awareness” or ”life perspective”.11,12 Some aspects that could be related to the construct of gain in caregiving might be recognition of the role by third parties and trust in the caregiver, although future versions incorporating these elements would need to be explored.30

This study has the limitation of a cross-sectional design, which prevents the assessment of the sensitivity to change of the instrument or the predictive validity on some outcomes, such as longitudinal caregiver burden. In addition, it was carried out in an urban context, and it could be that in rural settings there would be variations in metrics and validity, so we recommend that an invariance study be carried out taking this into account. However, the robustness of the validation tests used, and the results obtained provide confidence in the consistency and constructs found in future empirical validations.

In conclusion, the GAIN scale is a valid and reliable instrument for measuring positive aspects of care among informal caregivers of people with multimorbidity receiving home care and can be used in clinical and research settings, although its sensitivity to change needs to be determined in longitudinal studies. Its use in clinical practice allows areas of intervention to be identified from a salutogenic perspective and a better understanding of the factors that can be strengthened in caregivers to maintain their resilience during the process.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.