The socio-demographic and epidemiological changes of our environment are characterised by an increase in ageing, chronic illness, comorbidities and with it, a progressive escalation of the demand for care. These new demands and expectations of citizenship are accompanied by an evolution of health systems (technological advances, complexity of the healthcare network, limited resources), the need to develop new roles and competence in care, together with the opportunity that full academic development implies: Nursing undergraduate and posgraduate degrees. This is why, at present, it is necessary to reorient care models in order to achieve health care for more agile, efficient and better quality care processes, adapted to the needs and expectations of citizens and to the sustainability of health systems.

The Public Health System of Andalusia (SSPA) has developed, in recent decades, different nursing roles that include new competences, with the aim of responding to the needs of citizens.

The objective of this article is to present how the competences development framework of nurses has been configured in the SSPA, which also integrates advanced skills in care and advanced practice profiles (Clinical Nurse Specialists and Advanced practice nurses).

Los cambios socio-demográficos y epidemiológicos de nuestro entorno se caracterizan por el aumento del envejecimiento, la cronicidad, las comorbilidades y, con ello, una escalada progresiva de la demanda de cuidados. Estas nuevas demandas y expectativas de la ciudadanía se acompañan de una evolución de los sistemas sanitarios (avances tecnológicos, complejidad del entramado asistencial, recursos limitados), la necesidad de desarrollar nuevos roles y competencia en cuidados, junto a la oportunidad que supone el pleno desarrollo académico del grado y posgrado de Enfermería. Es por todo ello que, en la actualidad, se hace necesario reorientar los modelos de cuidados para lograr una atención sanitaria más ágil, eficiente y de calidad, adaptada a las necesidades y expectativas de la ciudadanía y a la sostenibilidad de los sistemas sanitarios.

El Sistema Sanitario Público de Andalucía (SSPA) ha desarrollado, en las últimas décadas, diferentes roles enfermeros que incluyen nuevas competencias, con el objetivo de dar respuestas a las necesidades de la ciudadanía.

El objetivo de este artículo es presentar cómo se ha venido configurando un marco de desarrollo competencial de las enfermeras y enfermeros en el SSPA, en el que se integran además las competencias de avance en cuidados y los perfiles avanzados de práctica (especialidades de Enfermería y Enfermería de Práctica Avanzada).

The increased complexity of healthcare organisations, and the ongoing search for management and professional development models require cost-efficient and effective responses to the new social challenges.1 This creates the need for healthcare organisations to develop different care planning models that include new nursing profiles and roles that can adapt to these new needs. The position of nurses in the healthcare context enables a flexible organisational system to be designed whose structure appropriately coordinates new services in an agile and efficient way.2

The definition of new competence roles has been included in different international and national settings, backed by the current legislative framework on competence development and scientific evidence.

Various strategies have been being developed in the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Policy and Equality for the care of patients with health conditions (oncological, palliative, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, mental health, chronic diseases) that coincide in the need to diversify and extend nurse competences. The Public Health System of Andalusia (SSPA), also in the framework of the Comprehensive Health Plans and Integrated Care Processes, has included the need to develop specific nursing competences and profiles for the provision of high-quality care, providing a safe environment that facilitates prevention and health promotion, patient recovery and improved quality of life.

Internationally, in countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Australia and Canada, these new roles have been promoted by factors of demand (ageing, chronic disease), and offer (more professionals with high levels of training, disproportion between demand for and accessibility of services intensified by the economic crisis, at the level of both primary and hospital care, changes in professional dynamics and expectations, opportunities of information, and communication technology).3 Roles of high professional competence have been being developed in many fields, from the care of acute hospitalised patients to the care of acute demand in primary care or hospital emergency departments, and transitional-navigation care services, and case management of patients with complex chronic conditions, services for people with serious mental disorders, human immunodeficiency virus, etc. The scientific evidence supports the inclusion of these new roles in health systems, due to their considerable results in terms of effectiveness.4–6 References are worthy of note such as the systematic review by Laurant et al.7 in different countries (United Kingdom, U.S.A., Canada and Holland) to study the effectiveness of advanced practice nurses (APN) in improving resource usage (number of consultations, hospital admissions, length of hospital stay), clinical results (morbidity, mortality, functionality, quality of life), and patients’ assessment of care (satisfaction, adherence to treatment). The subsequent review revealed reduced mortality and readmissions after inclusion of the APN in Primary Care processes.8 Integrating APN in interdisciplinary health teams, improves health and wellbeing, reduces costs, and improves patients’ quality of life.9 According to the results of the various systematic reviews, APN who attend patients with heart failure show reductions in mortality and hospital admissions.10,11 In the follow-up of patients with cancer, APN have also proven to provide significant impact on quality of life, on early initiation of palliative care, and even on survival.12,13 In conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, nurse-led care for the management of comorbidities and improved self-care has been shown to produce significant effects on the progression of joint symptoms, and the patients’ management of their disease.14 Likewise, the role of the advanced practice nurse has shown positive effects on the mental health of older adults in the community,15 on the management of depression in primary care,16 and in reducing acute readmissions, and improving social function for patients with psychosis17 and serious mental disease.

A profile of advanced nursing practice constitutes the basis for improving the sustainability of the system according to a many reviews.18–20 We would highlight the systematic review by Morales Asencio and Sarría Santamera, where alternative models for the care of patients with heart failure are proposed.21 The results of this review highlight the advantages in terms of readmissions, hospital stay, and quality of life by implementing nurse-led initiatives based on continuity and self-care. These results were later corroborated by Lambrinou et al.22 in a meta-analysis on the same subject, performed 6 years later. Along these lines of health problems that involve major health expenditure, which include diabetes, there are also meta-analyses with favourable results regarding the impact of nursing interventions on metabolic control.23

Of the studies performed in Andalusia for these advanced profiles, we would highlight the study by Morales Asencio et al. “ENMAD Study”, on the APN in case management, as an agent of sustainability demonstrated to achieve results in different variables. APN in case management for the care of chronic, complex patients have proved effective and decisive for a health system that requires efficiency and sustainability, improving results in detecting vulnerable populations (especially cases that remain “hidden” to the health services or those who emerge in other areas of care that are not appropriate for their problem), and in multi-professional coordination, diversification and participation in home care, and in the concurrence of harmonised resources.24,25

Competence development, excellence and advancement of care in the Public Heath System of AndalusiaThe needs and new demands of citizens requires the organisation of care within the health systems based on the current development of the nursing profession: degree qualification, postgraduate qualifications (masters and doctorate degrees), the implementation of specialised training through the resident nurse system and their integration in the diverse autonomous regions of Spain, in addition to the international and national development of the APN.

In Andalusia, since 2009, all the nursing specialties (except geriatric and medical-surgical) have been included in the development of specialist training through multi-professional teaching units formed by a combination of specialists from different disciplines. The specialties of midwifery and mental health had already been widely developed in the specialist training of the SSPA.

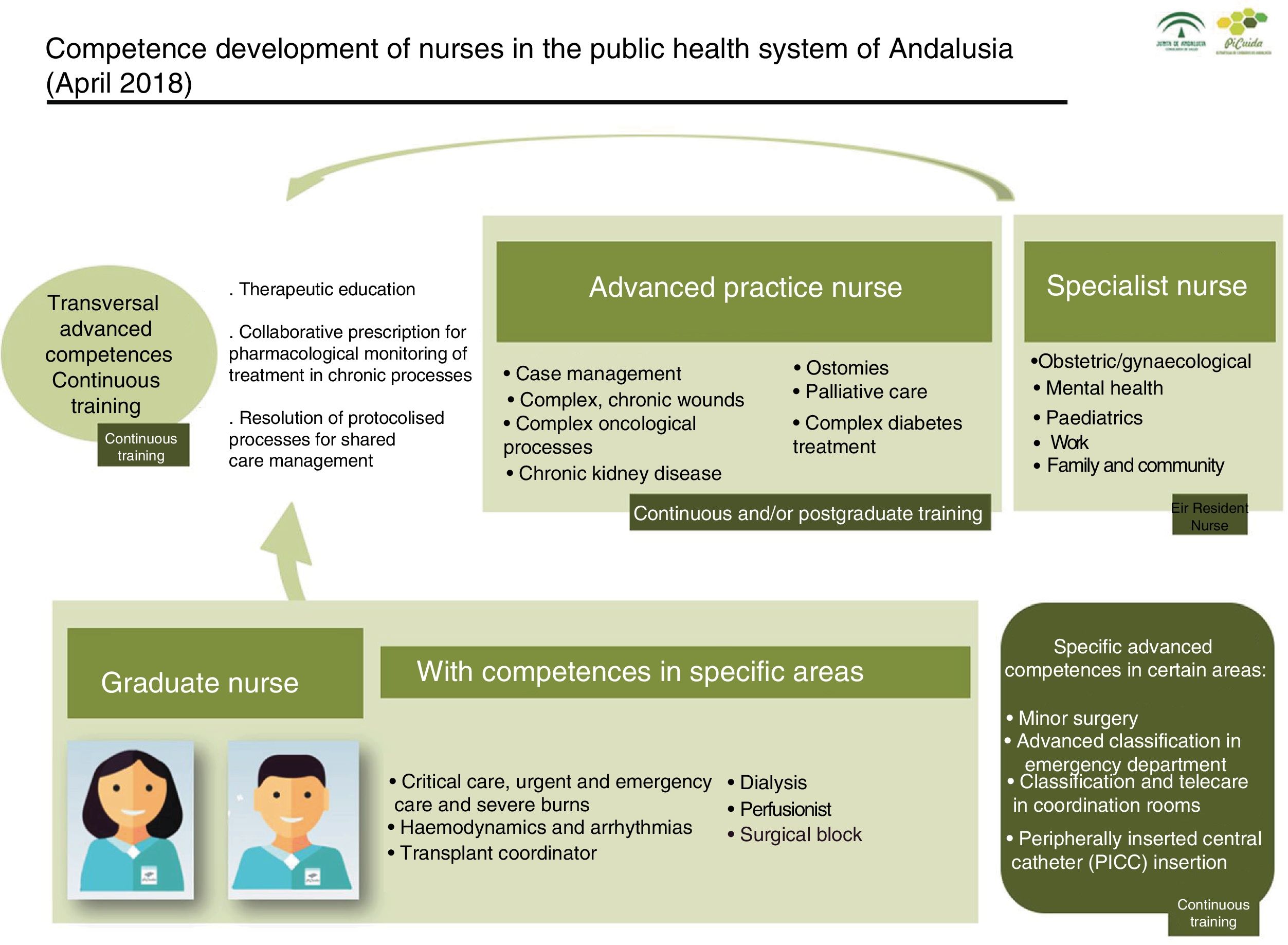

The coexistence of these practice profiles, APN and specialist nurses (SN), together with the inclusion of new competences for the advancement of care that they and graduate nurses have developed, require a definition of how a benchmark framework is being shaped for care provision in the SSPA, and how nurse competence development is currently being coordinated, and the specific role of each of these nurse profiles within the health system (Fig. 1).

A nurse with a diploma or degree qualification, who delivers care in various clinical environments, and who can update their knowledge using continuous training mechanisms provided through the health system itself, universities, professional organisations, trade unions or scientific societies.

The areas of practice of the graduate nurse can be relatively homogeneous, from a competence perspective, so that they can perform well in most nursing positions after a period of adaptation (most of the nursing positions in conventional adult hospital units, for example).

However, other positions require specific competence development relating to the particular severity of the patient's condition, complex health processes, complex technology, specific services offered or in responding to various organisational needs. Notwithstanding their being eliminated or other areas of practice identified that are candidates for specific competence development, the following specific positions were considered by the SSPA: critical care nurse, urgent and emergency care and severe burns, dialysis nursing, surgical block nurse, nurse perfusionist, haemodynamic and arrhythmia unit nurse, transplant coordinator nurse.

These specific competences could be acquired through specific continuous training that covers a minimum of hours of theoretical and practical training, delivered by entities, and training activities duly accredited by the Continuous Training Committee or the universities. A minimum amount of professional experience in the area of practice will also be required. In the SSPA all these positions for graduate nurses can be accredited, since the accreditation manuals are available relevant to each area.

Specialist nursesNurses who have obtained, through national specialist and formal training by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Policy and Equality, a higher qualification and training to practice professionally in a specific area of care practice, who require knowledge, skills and attitudes that are not provided by graduate training, to improve the safety and quality of care, and act to drive and promote improvements in their area of work.

Currently the SSPA is training and intends to incorporate or continue with the following nursing specialities defined by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Policy and Equality: SN in obstetrics and gynaecology (midwife), SN in mental health, SN in paediatrics, occupational nurse, specialist family and community nurse.

In order to incorporate the SN, the health system must be responsible for defining the competences for career advancement that the inclusion of these new profiles would involve, with a view to broadening the response to care in these specific areas by developing these practice roles.

Incorporating specialist profiles will add value towards achieving care excellence in the context of the specialty. A change to the functions and competences of nurses in these areas of practice would occur as they take on their roles as specialists. And finally, work would be reorganised between doctors, nurses and the other professionals who form the health teams. The reorganisation of competences that could occur with the incorporation of nursing specialties would have a positive economic impact, and improve efficiency in service planning. This reorganisation of competences seeks to help all professionals to develop on the competences they have learned in training programmes, and requires each professional group to develop these competences through the health system with criteria of qualification and cost-effectiveness. This would make it feasible for doctors, SN, general nurses, and APN to work in the same unit, along with other professionals required by the specific features of the unit.

After defining, developing and taking up positions in these specialties, coordinated with other nurses in their area of knowledge, the relevant development accreditation manuals will need to be designed for these professionals, as has already taken place in the SSPA with midwifery.

Advanced practice nursesThere are currently different care-related health problems that are not being solved with the traditional care approach. A qualitative analysis performed with the participation of the public in designing the current Andalusian care strategy flags up some needs in this regard,26 which can be met by incorporating APN, as we have mentioned earlier.

APN have acquired expert knowledge using formal and regulated mechanisms, and by developing their practice in a care setting. They organise their competences to respond to specific needs, reinforcing, augmenting or including new services to those already existing in the health system to achieve better accessibility, coordination, efficiency, and health outcomes.

The nurses who have developed this profile are clinical leaders in their working environment, with autonomy for complex decision-making, based on applying evidence and research results to their professional practice. They integrate 4 roles in their practice: clinical expert, consultant, teacher and researcher.27–29 Furthermore, also worth highlighting is their role as motivators and cohesive elements within care teams, and in the support and follow-up of processes, enhancing continuity of care, and intra and inter-level coordination.

The roles of APN must be defined by the health systems in a unique and specific way, since they can change according to the needs of the public, and the competence advancement of graduate nurses. Therefore their roles should adapt given the changing nature of needs and health problems in a specific time and context.

Different APN roles have already been implemented and piloted in the SSPA in areas where there is no clearly defined nursing specialty that require an advanced care response: case management, care of people with complex, chronic wounds, care of people with stomas, and care of people with complex oncological processes.

New APN roles are currently being designed to cover new needs and demands: the care of people with complex diabetes treatments, care of people in palliative care, care of people with advanced chronic kidney disease (ACKD).

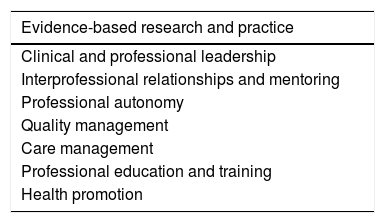

To be appointed to the post, expert knowledge is required in the area of care, specific training (accredited and acquired through continuous or specific postgraduate training) and clinical experience (a minimum time in the specific clinical area), so that it is ensured that the APN has the relevant minimum competences. In an adaptation of the definition of APN competence domains by Sastre-Fullana et al. (Table 1), the SSPA defines the following criteria or attributes for advanced practice nurses in our health system:

- 1.

Leadership, acting as a reference point for complex care in their area, with autonomy in decision-making on problems relating to patients under their care.

- 2.

Coordination of complex care, organising the components of the care, and adapting healthcare to the needs of patients and their caregivers, providing proactive health problem management, activating the resources to cover needs and acting as a service intermediary for problem-solving, and maximising continuity of care.

- 3.

Consultant for other professionals, and reference point for their learning.

- 4.

Driver of change through leadership, to promote innovations, improving clinical practice by transfer of knowledge and evidence in their care environment, and affecting changes to practice styles, and orientation towards quality.

- 5.

Promotion of research in their area of practice.

Competence domains of the advanced practice nurse.

| Evidence-based research and practice |

|---|

| Clinical and professional leadership |

| Interprofessional relationships and mentoring |

| Professional autonomy |

| Quality management |

| Care management |

| Professional education and training |

| Health promotion |

Source: Sastre-Fullana et al.30

These positions could be accredited in specific accreditation processes. The relevant professional development accreditation manuals are available in the SSPA for the APN profiles that have been implemented to date.

Advanced competences: transversal and specificGraduate, specialist and advanced practice nurses will advance and develop their profile by acquiring skills in their area of practice, with a view to: improving the accessibility and safety of the public; promoting results orientation, increasing care quality; enhancing professional development, and contributing to the sustainability of the health system.

These competences are considered necessary for optimal performance in the position and for the advancement of the care response of the health system to the needs of Andalusian citizens from the perspective of care, forming part of the SSPA's service portfolio. The definition of these competences, with a marked strategic component, is established from the health system itself for the development of the various professional practice profiles, and for improving the services offered.

The following are currently considered transversal advanced competences: therapeutic education, collaborative prescription for pharmacological monitoring of treatment for chronic processes, resolution of protocolised processes for shared care management.

Furthermore, there are other specific advanced competences yet to be developed in some areas or specific posts, such as: minor surgery, peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) insertion, advanced classification in the emergency department, and classification and telecare in coordination rooms.

ConclusionsNursing as a discipline has evolved in terms of training and education to become a degree with the possibility of obtaining master's and doctorate degrees, and opting for specialist training and training to undertake advanced practice within the health systems. With this improvement in competences, from within the health systems, it is essential to readjust competence ceilings to the response that the new professional profiles can now give, reorienting the possibilities of professional development within the system to improve care to the benefit of the public, underpinned by improved sustainability of the health system itself.31

The SSPA, as a pioneering and innovative health system in many of the care developments and advances that have occurred in Spain over the last decades, remains committed to the advancement of care with the effective inclusion, coordination and planning of these new professional nurse profiles in the different care settings.

To that end, we draw on previous international trends and experiences in the integration of these new practice roles nationally and internationally, and the available scientific evidence on the effectiveness and previous results of these professional profiles, and the development of new advanced competences in the system.

Care demands and health needs are changing and pose constant challenges for the health services. They also require new responses and developments on the part of advanced nursing services. This is why the framework of integrating nursing profiles and advanced care competences into the healthcare system defined in this article will require further reviews, as these changes evolve.

FundingNo financing was received.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Lafuente-Robles N, Fernández-Salazar S, Rodríguez-Gómez S, Casado-Mora MI, Morales-Asencio JM, Ramos-Morcillo AJ. Desarrollo competencial de las enfermeras en el sistema sanitario público de Andalucía. Enferm Clin. 2019;29:83–89.