Pneumothorax is a common condition that is easy to diagnose by ultrasound. The sensitivity of this technique is greater than that of plain radiography, which is commonly used for diagnosis. In addition, ultrasound allows the pneumothorax to be semi-quantified, facilitating assessment of those that are and are not amenable to drainage. Increased sensitivity and speed are sufficient reasons to use ultrasound to diagnose this condition, improving the prognosis of these patients.

We present the case of a 27-year-old obese man (BMI 33), with no other medical history of interest, who was admitted for bilateral pneumonia secondary to COVID-19 infection, on the eighth day after the onset of his symptoms. Twenty-four hours after admission, he exhibited respiratory progression, developing Acut respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), diagnosed by chest X-ray. The patient was undergoing thromboprophylaxis (enoxaparin 60 mg daily) and at that time anti-inflammatory treatment was started with tocilizumab and dexamethasone boluses at 20 mg daily, in addition to increasing oxygen requirements with a reservoir at 15 L/min.

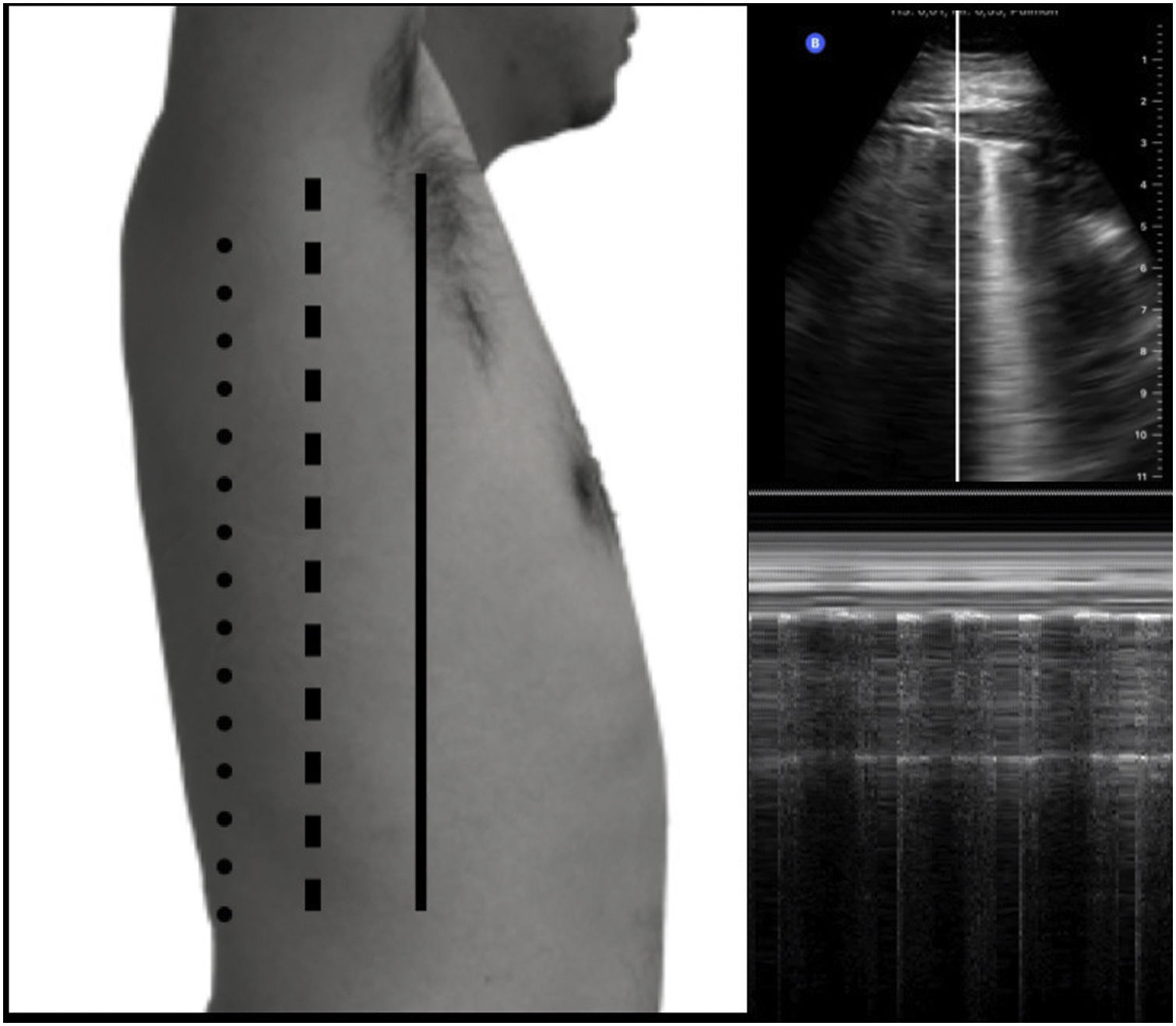

Subsequently, the patient's clinical course was favourable, gradually reducing the oxygen but without achieving its complete withdrawal. As the patient improved further, in the third week from the onset of his symptoms, he experienced an episode of chest pain. The pain was sharp, increased with coughing and was located on the left side. It did not change with body positions. Regarding laboratory tests, acute phase reactants continued to decrease, while D-dimer levels of less than 500 ng/mL were of note. An electrocardiogram was conducted, which revealed sinus rhythm without alterations compatible with acute ischaemia, and myocardial enzymes were negative. A bedside lung ultrasound was performed, revealing multiple subpleural band consolidations in posterior lung fields and the presence of heterogeneously distributed B lines in anterior and lateral lung fields. The presence of lung point at the left midclavicular line, consistent with spontaneous pneumothorax, was of note. It was semi-quantified, concluding that it was small and not amenable to drainage (Fig. 1A–C).

(A) Anterior axillary line (AAL; continuous black line), midaxillary line (MAL; dashed black line) and posterior axillary line (PAL; dotted line). (B) Representation of the placement of the M-mode line. (C) Graphic representation of the M-mode; an alternating grainy pattern (asterisk) and stratosphere sign can be seen. If the lung point is found anterior to the AAL, it would be suggestive of mild pneumothorax <10%; if the lung point is found on the MAL, it would be suggestive of pneumothorax between 11–30%; if it is posterior to the PAL, it would be suggestive of pneumothorax >30%.

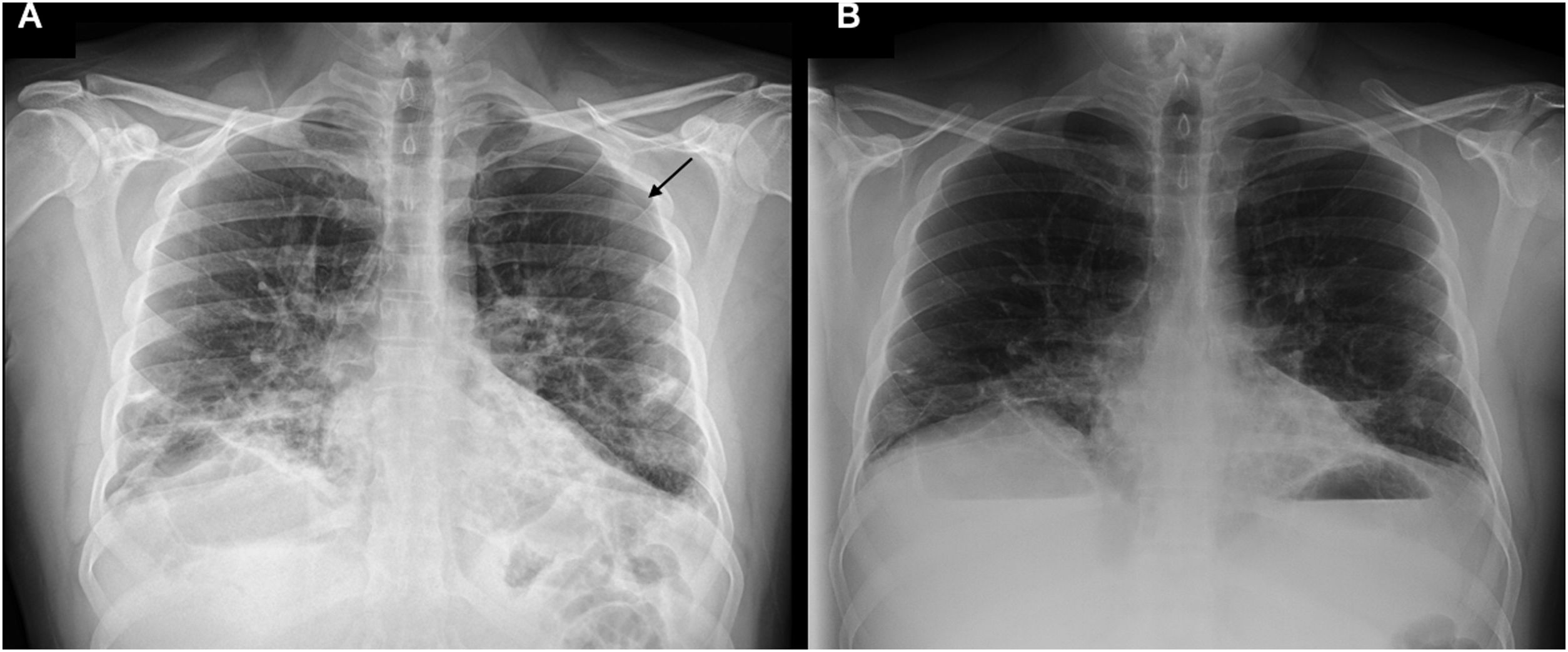

A chest X-ray was also performed, which confirmed the pneumothorax (Fig. 2A). After 48 h, both the chest X-ray (Fig. 2B) and the lung ultrasound were repeated, revealing resolution of the clinical picture.

Lung ultrasound is a bloodless and rapid test that allows us to detect multiple complications that can occur during COVID-19 infection in a patient with chest pain, such as pulmonary thromboembolism, acute viral pericarditis or pneumothorax.1 In addition, this test has been shown to have a sensitivity and specificity very similar to computed tomography and greater than that of plain radiography.2 Subpleural consolidations, pleural irregularities and B-lines showing a patchy distribution in the context of this pandemic may suggest lung involvement due to COVID-19.2 In patients with traumatic pneumothorax or in those in the supine position, the sensitivity of plain radiography decreases, making the use of clinical ultrasound even more important.

Diagnosis is based on the detection of a sign known as "lung point". This ultrasound sign is pathognomonic of pneumothorax and consists of the coexistence of findings consistent with a healthy lung (presence of A lines and lung sliding) and pneumothorax (absence of lung sliding). Ultrasound allows us to semi-quantify the pneumothorax based on the location of the "lung point" compared to the midaxillary line and, in turn, also allows us to conduct follow-up to assess the improvement or worsening of the pneumothorax depending on the displacement of the "lung point" compared to the aforementioned line.3

It can be classified as follows:

- none-

Class 1 (<10% collapse): lung point located anterior to the midaxillary line.

- none-

Class 2 (11–30% collapse): lung point located on the midaxillary line.

- none-

Class 3 (>30% collapse): lung point located posterior to the midaxillary line.

In light of the above, it can be concluded that ultrasound is essential for rapidly diagnosing a condition such as pneumothorax with greater sensitivity than with a plain radiography, particularly regarding post-traumatic, post-procedural and spontaneous pneumothorax.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Pérez M, Tung-Chen Y, Herrera-Cubas R, Detección y semicuantificación de neumotórax mediante ecografía pulmonar: a propósito de un caso de COVID-19, Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:524–525.