The case discusses a 12-year-old male who was treated at the Dermatology Department of the Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez, originally from Iguala Guerrero (south-eastern Mexico). He presented with disseminated dermatosis, which had started six months previously, of the anterior chest and right axillary regions, and on the ventral surface of the ipsilateral right arm, made up of five nodules measuring 2×1cm, slightly erythematosus, firm, not painful, non-fistulising and without exudate (Fig. 1). He reported that the dermatosis started one month after falling from a motorbike, in which initially he only presented with minor bruising.

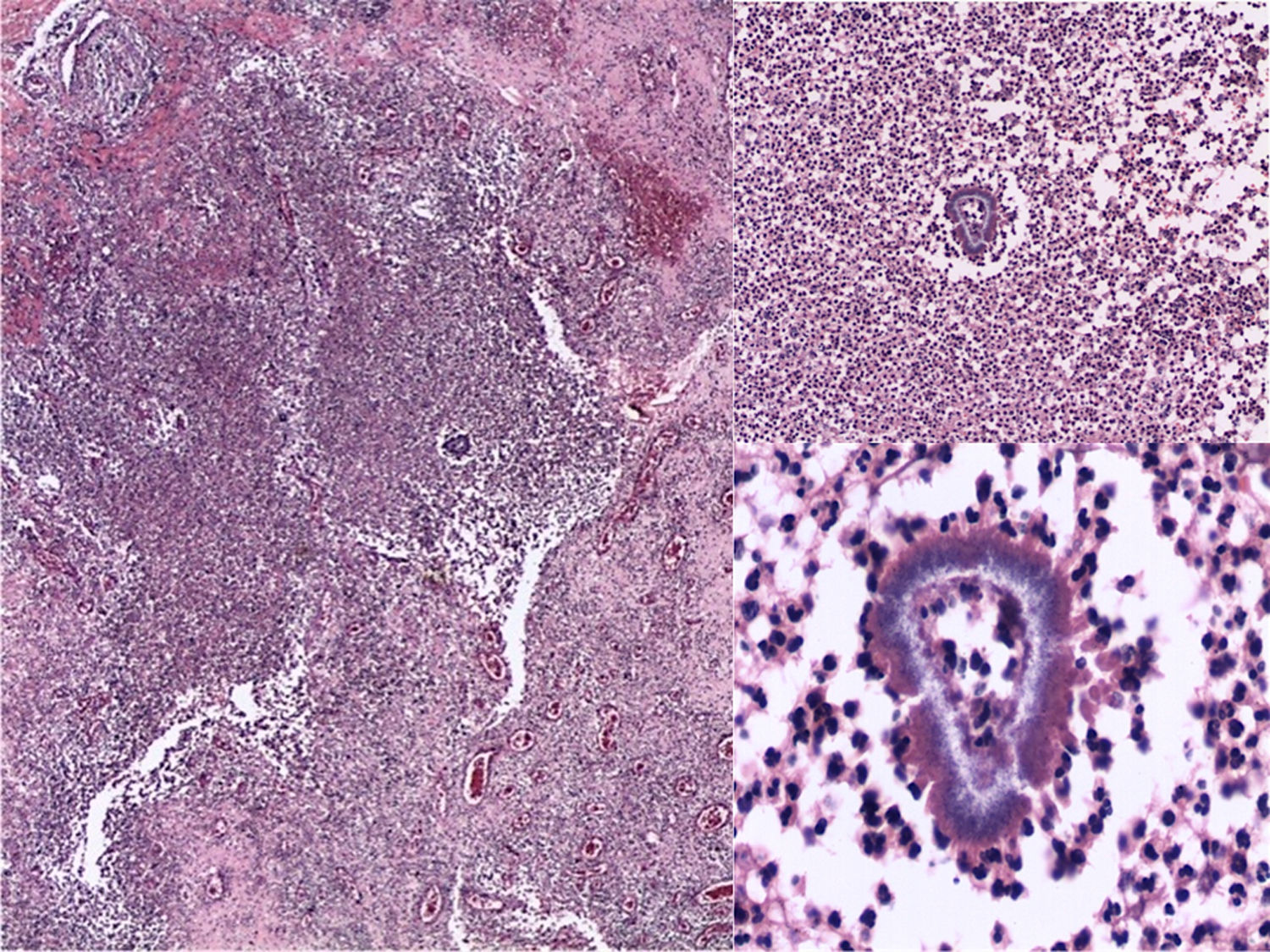

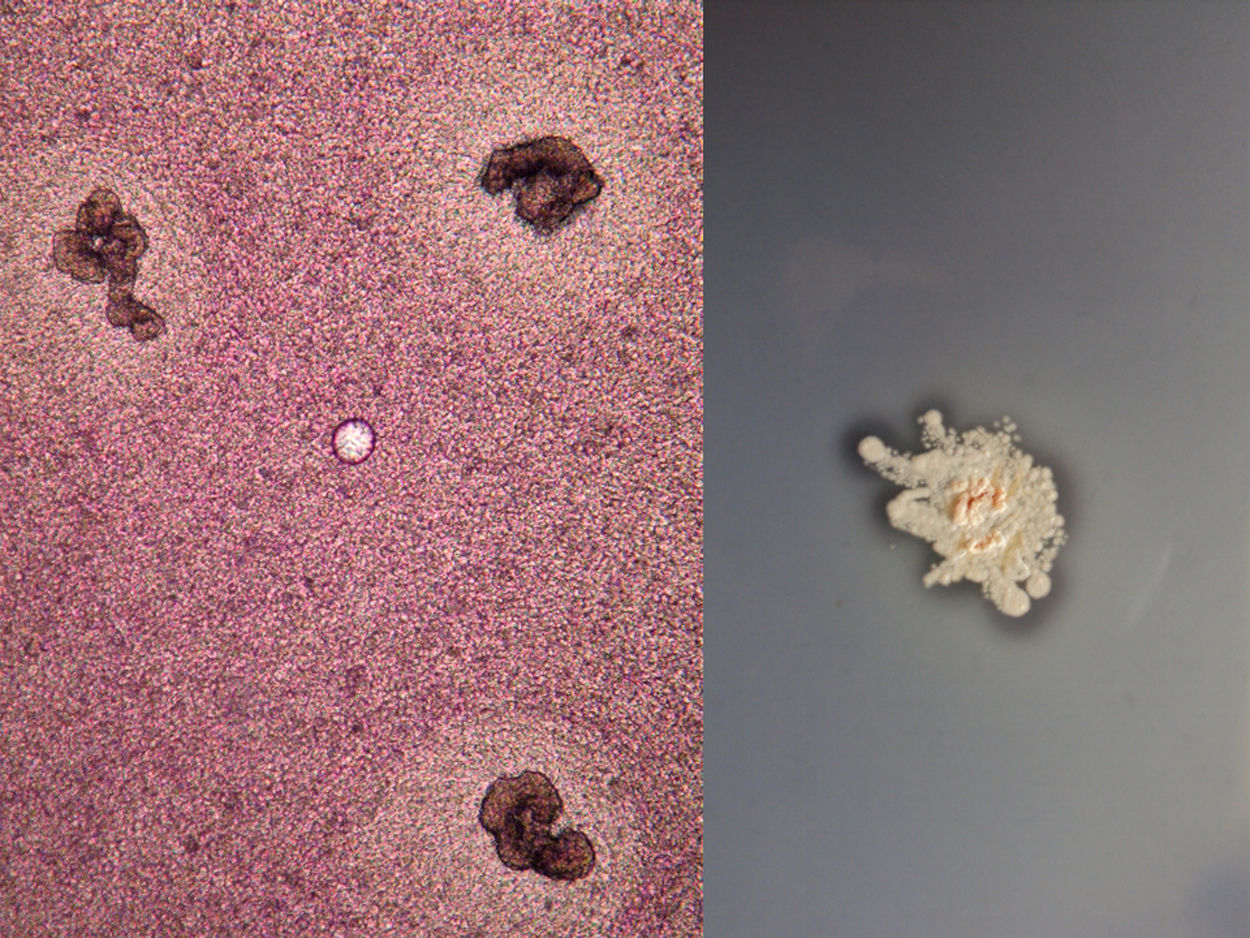

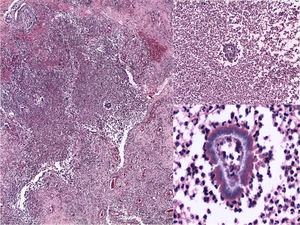

Clinical diagnosis and courseGiven the suspicion of deep mycosis, a biopsy was performed. In the reticular dermis and subcutaneous cellular tissue a diffuse dense inflammatory infiltrate was observed, composed of neutrophilic microabscesses, histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells, with formation of granulomas and kidney-shaped granules (Fig. 2). In the mycological study, multiple small, kidney-shaped granules were observed in the direct examination (KOH 10%) with spikes in the periphery, corresponding to the Nocardia type (Fig. 3). Limited, white, rocky colonies developed in the culture in Sabouraud dextrose agar media. These were identified by biochemical tests and by amplification and sequencing of the gene 16S rRNA. It was based on the sequencing of the gene 16S rRNA, using the primers: Noc1 (5′-GCTTAACACATGCAAGTCG-3′) and Noc2 (5′-GAATTCCAGTCTCCCCTG-3′). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product was purified and analysed in a DNA sequencing of Applied Biosystems® 3730 system (Foster City, CA, USA). The 16S sequence showed a 100% homology with Nocardia brasiliensis.1 The access number to the GenBank sequence was: MK603972. Based on the above, the diagnosis of actinomycetoma caused by N. brasiliensis was confirmed.

The chest and right arm X-rays ruled out bone involvement. The white blood cell and reticulocyte count, liver enzymes and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase levels were normal. Treatment was therefore started with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160/800mg/12h and diaminodiphenyl sulfone 50mg/day. The patient presented improvement from the second month of treatment, with no evidence of adverse effects, and completed six months of treatment, obtaining clinical and microbiological cure.

Final commentsMycetoma is a subcutaneous chronic and localised infection due to implantation. It is divided into two: eumycetoma caused by filamentous fungi and actinomycetoma caused by aerobic filamentous actinomycetes2; the first type is most common in Africa and India and the second is most common in America, mainly in Mexico and Venezuela.2–5 The countries with the greatest prevalence are in the area called the ‘mycetoma belt’ latitude 15° south and 30° north of the Tropic of Cancer), subtropical and tropical dry climate regions.2,3,5 Mexico is the country with the highest number of reports in America, in particular cases of actinomycetoma caused by Nocardia brasiliensis in up to 80% of cases3,5; it affects more males between 21 and 30 years of age, and is considered an occupational disease, with the most affected individuals being those who work in the countryside with minimal protection.2,3,5 Actinomycetoma in children is a rare entity. It is observed more in endemic areas and its explanation is that they also work in the countryside with little protection or due to living in rural areas in which they are more exposed to traumas which are a means of entry for fungi and actinomycetes.2,3,6–8 In an extensive Mexican report (3993 cases), mycetomas under the age of 15 represent 3.94%, with predominance in males and due to N. brasiliensis.5

There are three factors for its development: appropriate inoculum, immunological status and hormonal adaptation.5,8 The absence of sex hormones in pediatric patients is probably related to the lower frequency.5,8,9

The clinical manifestations in children and adults are similar; they are common in lower limbs (70%) and rare on the trunk. In children, they are specifically reported in 0.1%.6–9 The clinical manifestation is of lesions with increased volume, deformation, nodules and fistulas through which a stringy exudate containing parasitic forms called “granules” drains. In children and adolescents, a limited clinical form of nodular lesions has been reported which rarely develop into a fistula and which are called “mini-mycetoma”. These clinical symptoms are very similar to the nodules of our patient. Mild pain and a little itchiness may be presented.3,6,8,9

The diagnosis is confirmed with the observation of the “granules” either in the direct examination or through the histopathology. The latter is made up of chronic suppurative granulomas and polymorphonuclear microabscesses. Cultures are fundamental to determine the aetiology and in vitro susceptibility tests can be performed. Molecular identification of actinomycetes such as Nocardia is often done using PCR techniques (16S rRNA gene), which is the technique with the greatest specificity and is considered as the gold standard.1,3,6,8

Treatment depends on the causative agent and on the patient's condition. In the case of actinomycetoma caused by Nocardia, the combination of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and diaminodiphenyl sulfone has been used both in children and in adults. These achieve recovery in most cases and are well tolerated despite being indicated for a prolonged period of time (6–8 months).8–10 In the event of therapeutic failure, the use of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, amikacin and imipenem may be considered.5,8

Please cite this article as: Medina-Torres AM, Toussaint-Caire S, Hernández-Castro R, Bonifaz A. Nódulos cutáneos en un paciente pediátrico mexicano posterior a traumatismo en tórax. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019;37:611–613.