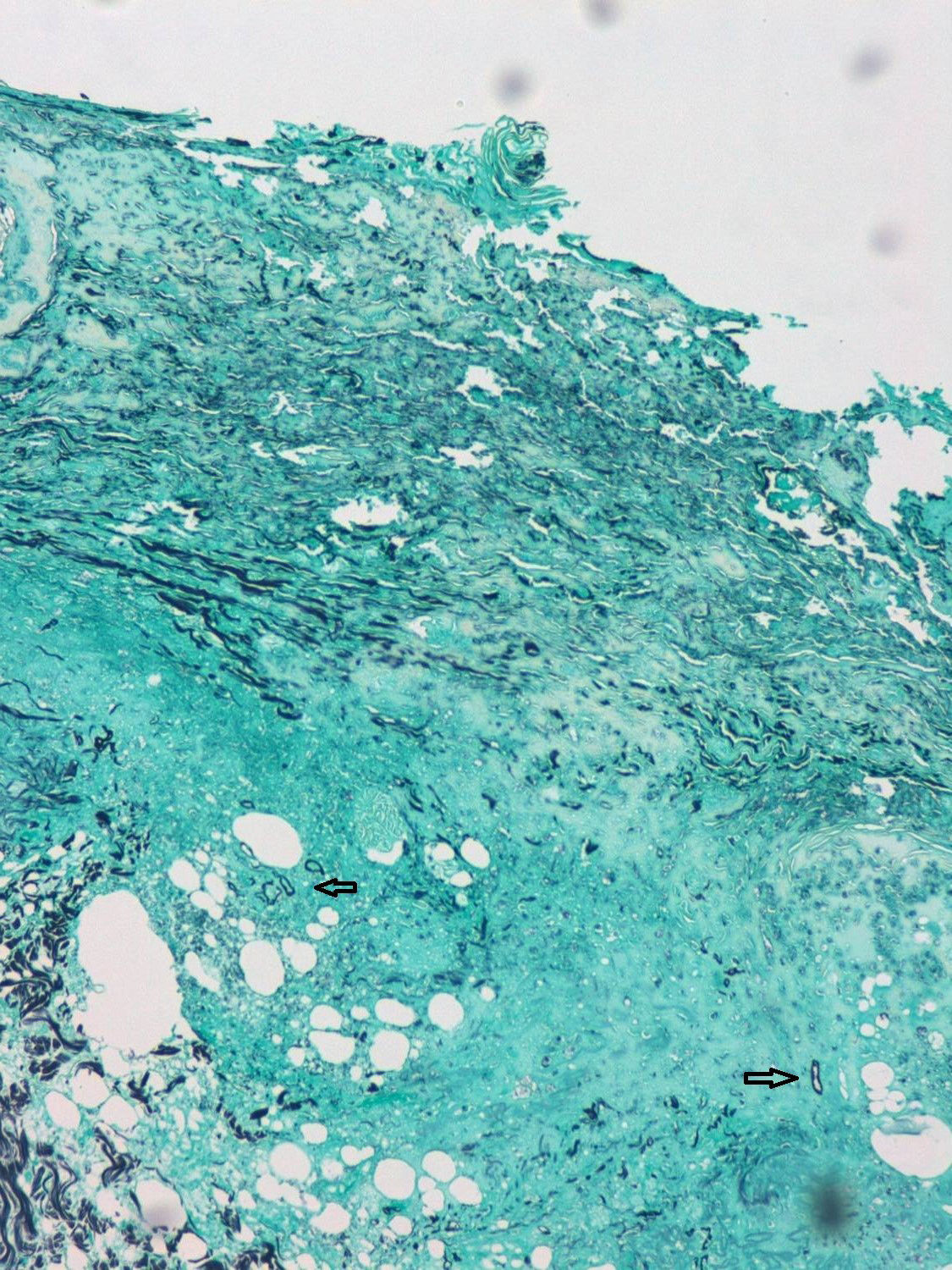

A 55-year-old male patient with a diagnosis of acute myeloid leukaemia, treated one year ago with haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) from an HLA-matched sibling. He is currently receiving prophylactic treatment with valgancyclovir and co-trimoxazole, together with prednisone 30mg/day and cyclosporin 150mg/day due to a history of graft versus host disease. The patient was admitted to haematology due to symptoms of acute kidney failure and pancytopenia without neutropenia. During admission, dermatology was consulted due to the rapid appearance, in just 24–48h, of a painless lesion on the forehead without associated fever, in spite of empirical treatment with meropenem. He was not aware of any trauma or pre-existing lesion in the area. The physical examination revealed a reddish-purple cellulitic plaque of around 10cm, with areas of necrosis and ulceration and formation of a scab following the path of the right supratrochlear artery (Fig. 1). Skin biopsies were taken for histology as well as fungal and bacterial cultures, and liposomal amphotericin B was given at a dose of 5mg/kg/day. Histology revealed complete necrosis of the epidermis and dermis with vascular thrombosis. A Grocott–Gömöri stain revealed the presence of aseptate thick-walled, fungal structures with irregular morphology (Fig. 2).

The histological findings were compatible with mucormycosis, which was confirmed by a culture positive for Rhizopus oryzae in the first 48h. Blood cultures were negative.

Given the severity of the patient's condition, his family decided to limit therapeutic efforts and, therefore, surgical debridement was not performed. The patient died several days later due to multiple organ failure.

CommentsMucormycosis or zygomycosis is an opportunistic infection caused by fungi of the order Mucorales, with 80% of cases being caused by the species R. oryzae. These are ubiquitous fungi that live as spores in soil, air, vegetation and on the hands, contaminating hospital materials, including culture samples. Infection leads to an emboligenous and potentially fatal angiodestructive process if treatment is not started early, which requires a high degree of suspicion and recognition of the risk factors that facilitate infection.1

The main risk factor is immune deficiency, primarily that associated with diabetes mellitus, systemic corticosteroid treatment, neutropenia, malignant haematological neoplasms, solid organ transplant and HSCT.2 Mucorales use iron to proliferate, so situations associated with iron overload increase the risk of disseminated infections. Deferoxamine, an iron chelator used in kidney failure, acts as a siderophore on the membrane of Mucorales, directly supplying them with iron from the plasma.3 It is important to remember that prophylactic use of voriconazole in immunocompromised patients does not constitute a protective factor, as the organisms have intrinsic resistance to this treatment.

Cutaneous mucormycosis is divided into primary, caused by direct inoculation, or secondary, caused by haematogenous dissemination, generally from an underlying rhino-sinusal focus. Both forms present as cellulitis that progresses rapidly to a necrotic ulcer, with formation of a scab resembling ecthyma gangrenosum. The differential diagnosis in haematological cancer patients with necrotic lesions should be made primarily with other opportunistic fungal infections, especially Aspergillus and Candida, with Cryptococcus, Alternaria, Fusarium and Penicillium being less common aetiologies. Bacterial infections such as ecthyma gangrenosum and necrotising fasciitis are the other major differential diagnosis. With regard to non-infectious causes, cutaneous tumour infiltration, paraneoplastic vasculopathies or vasculopathies secondary to HSCT should be considered.4 In mucormycosis, direct visual assessment and histology typically show fungal structures in the form of thick, wide, aseptate hyphae with irregular 90° branches. This makes diagnosis possible, with a culture being necessary to concretely identify the species. Blood cultures and cultures from non-sterile samples may represent contamination, and must therefore be combined with histology to demonstrate tissue involvement and, by extension, infection.

Treatment should be started upon clinical suspicion and should comprise three approaches: liposomal amphotericin B 5mg/kg/day, surgical debridement and correction of predisposing factors. Posaconazole is the only oral drug approved by the FDA for mucormycosis, although oral isavuconazole is currently in phase 3 clinical trials and has demonstrated greater activity than posaconazole.5 Other treatments include hyperbaric oxygen, although without clear scientific evidence.6

Please cite this article as: Sahuquillo-Torralba A, Garrido-Jareño M, Llavador-Ros M, Botella-Estrada R. Placa necrótica frontal rápidamente progresiva en paciente inmunodeprimido. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:315–316.