Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae, an intracellular microorganism bound with great tropism by the skin and peripheral nervous system. The classification system of Ridley and Jopling1 describes 5 forms of disease based on the clinical, microbiological, histological and immunological characteristics of the patient; it establishes lepromatous leprosy (multibacillary form) and tuberculoid leprosy (paucibacillary form) as the 2 polarised ends of the clinical spectrum. Lepra reactions are acute exacerbations of Hansen's disease (HD)2 described in 30–50% of patients and are responsible for the mortality associated with this disease. Classically, 2 forms have been described: the type 1 or upgrading reaction, and the type 2 reaction or erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL).

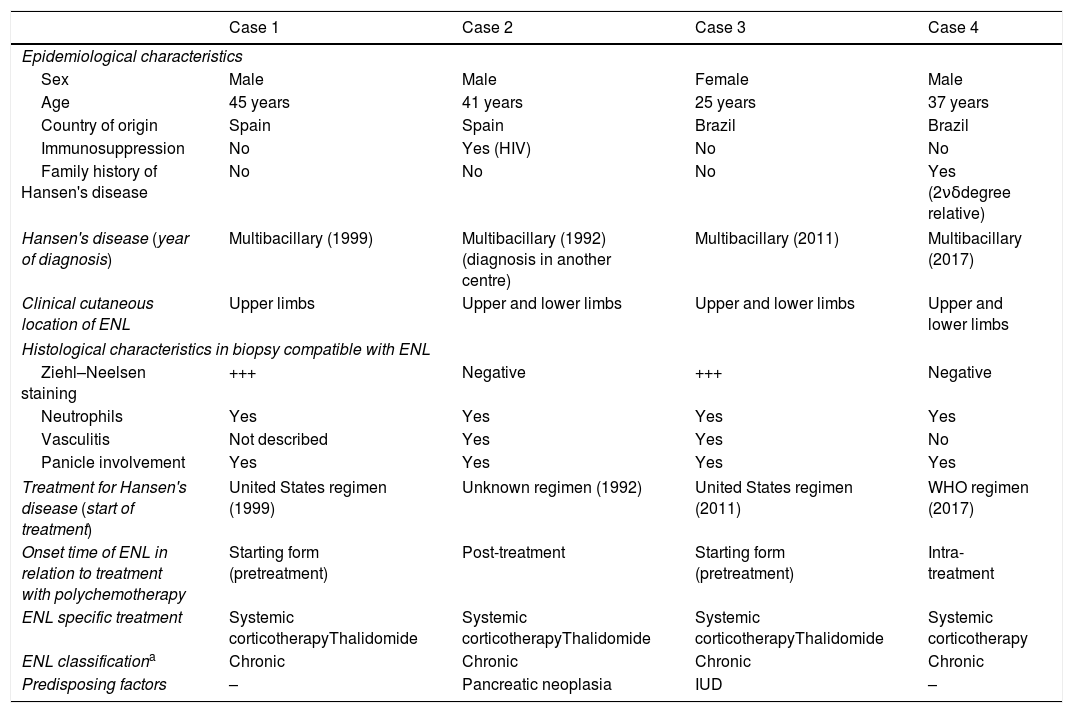

We present 4 cases of ENL treated in our department from March 1999 to May 2019 (Table 1). They involve 3 males and one female, with a median age of 39 years. The diagnosis and follow-up of the ENL was carried out in our centre in all cases. Cases number 3 and 4 originated in Brazil, and the latter referred to a diagnosis of HD in a second-degree relative, while cases 1 and 2 were patients with non-imported HD. In 2 of the cases, the ENL presented as a form of disease onset without having yet started treatment with targeted multitherapy (MDT). In all of them, the skin examination showed multiple erythematous, indurated, painful nodules in the upper and lower extremities. Case 3 also presented fever, weight loss and watery rhinorrhea. The diagnosis of a pancreatic neoplasm, the implantation of a levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device and the onset of MDT are the identifiable factors as possible triggers in these patients. The histological study of the lesions showed the presence of neutrophils (4/4), leukocytoclasia (2/4) and inflammatory infiltrate in the adipose panicle (4/4). Ziehl–Neelsen staining showed the presence of acid-alcohol resistant bacilli (AARB) in 2 cases. After diagnosis, all patients began treatment with systemic corticosteroids (0.5mg/kg/day), with case 3 requiring intravenous treatment at a higher dose. Given the strong tendency to recurrence, thalidomide treatment (200–400mg/day depending on weight) was initiated in 3 of them, ignoring the evolution of case 1, due to loss to follow-up. As an adverse effect, drowsiness and the feeling of dizziness-instability were frequent at the beginning of treatment and with subsequent development of tolerance. In case 2, thalidomide was started at a dose of 400mg/day, maintaining the same dose until clinical control, with a subsequent decrease of 50mg/day every week, until complete suspension. In case 3, the patient experienced amenorrhoea at the beginning of treatment; she started at a dose of 200mg/day that is currently maintained owing to recurrence if suspended. During follow-up, serial smears were performed with strictly negative results in all patients.

Clinical–epidemiological characteristics and classification of ENL cases.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiological characteristics | ||||

| Sex | Male | Male | Female | Male |

| Age | 45 years | 41 years | 25 years | 37 years |

| Country of origin | Spain | Spain | Brazil | Brazil |

| Immunosuppression | No | Yes (HIV) | No | No |

| Family history of Hansen's disease | No | No | No | Yes (2νδdegree relative) |

| Hansen's disease (year of diagnosis) | Multibacillary (1999) | Multibacillary (1992) (diagnosis in another centre) | Multibacillary (2011) | Multibacillary (2017) |

| Clinical cutaneous location of ENL | Upper limbs | Upper and lower limbs | Upper and lower limbs | Upper and lower limbs |

| Histological characteristics in biopsy compatible with ENL | ||||

| Ziehl–Neelsen staining | +++ | Negative | +++ | Negative |

| Neutrophils | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Vasculitis | Not described | Yes | Yes | No |

| Panicle involvement | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Treatment for Hansen's disease (start of treatment) | United States regimen (1999) | Unknown regimen (1992) | United States regimen (2011) | WHO regimen (2017) |

| Onset time of ENL in relation to treatment with polychemotherapy | Starting form (pretreatment) | Post-treatment | Starting form (pretreatment) | Intra-treatment |

| ENL specific treatment | Systemic corticotherapyThalidomide | Systemic corticotherapyThalidomide | Systemic corticotherapyThalidomide | Systemic corticotherapy |

| ENL classificationa | Chronic | Chronic | Chronic | Chronic |

| Predisposing factors | – | Pancreatic neoplasia | IUD | – |

IUD: intrauterine device; ENL: erythema nodosum leprosum; WHO: World Health Organisation.

A type 2 lepra reaction is an acute inflammatory condition characteristic of multibacillary forms.4 Lepra reactions occur as a result of the imbalance between the patient's immune system and the mycobacterium produced, in many cases, by the initiation of the targeted antibiotic treatment; however, multiple causes have been documented as triggers (drugs, infections, pregnancy, contraceptive treatment). Underlying type 2 is a Gell and Coombs type III hypersensitivity mechanism,4,5 with the formation of circulating immunocomplexes that are deposited in the vascular wall. Subsequently, polymorphonuclear recruitment occurs6 in addition to the subsequent leukocytoclastic vasculitis that can affect multiple organs and tissues (fever, arthritis, osteitis, myositis, iridocyclitis, rhinitis and the characteristic neuritis). Depending on the cutaneous tissue damage, we can find (Fig. 1) erythematous macules, erythema multiforme-like lesions, subcutaneous nodules, extensive purpura or even necrotic areas (Lucio phenomenon, typical of patients with diffuse lepromatous leprosy).7,8 The treatment includes the non-suspension of MDT, the prevention of new outbreaks by avoiding triggers (precaution with hormonal contraception) explaining the situation to the patient, and avoiding therapeutic abandonment. Systemic corticosteroids should be used at doses of 0.5–1mg/kg/day, with a decrease of 10mg/every 15 days and, in the case of cortico-dependence or no response, thalidomide9 can be used as first-line treatment (with the mandatory combination of dual contraception in women of childbearing age). Effective alternatives include clofazimine and the use of anti-TNF in isolated cases published with good response.10

Clinical manifestations of cutaneous type 2 lepra reaction. (A) Subcutaneous, indurated and painful nodule in the auricular pavilion. (B) Nodule on the extensor face of the arm. (C) Erythematous oedematous plaques with central vesiculation, similar to erythema multiforme. (D) Violet-coloured erythematous papules that can evolve to necrosis and ulceration.

The duration of the ENL is not established, and it can occur before, during and up to several years after the end of the MDT treatment, so it should be considered as a complication of the disease in the control and long-term follow-up of these patients.

FundingThe authors declare that they have received no funding for the drafting or publication of this article.

Please cite this article as: Nieto-Benito LM, Sánchez-Herrero A, Parra-Blanco V, Pulido-Pérez A. Manejo y experiencia clínica en eritema nudoso leproso en 4 casos. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2020;38:243–245.