Pertussis incidence has increased in recent years, especially among infants aged <2 months. A number of Spanish regions have started a vaccination programme with Tdap vaccine to all pregnant women in the third trimester of pregnancy. An observational study has shown that this strategy reduces the number of cases of pertussis by 90% in infants aged <2 months. Mathematical models showed that a cocooning strategy (i.e. vaccination of the mother at immediate postpartum, and other adults and adolescents who have close contact with the newborn and caregivers) will reduce the incidence of pertussis by 70% in infants aged <2 months. It is intended to conduct a clinical trial in which 340 pregnant women will receive Tdap vaccine, whereas another 340 pregnant woman will be vaccinated soon after delivery. Vaccination with Tdap will be offered to all partners and caregivers of the newborn. After assessing both the ethical and scientific reasons supporting the trial, it is concluded that it is ethically and legally acceptable to invite pregnant women living in communities where Tdap vaccination has been implemented to participate in the trial.

La incidencia de tos ferina ha aumentado últimamente, afectando especialmente a lactantes menores de 2 meses. Varias comunidades autónomas han iniciado un programa de vacunación con dTpa a todas las mujeres gestantes en el tercer trimestre de embarazo. Un estudio observacional ha mostrado que esta estrategia reduce la incidencia de tos ferina en lactantes <2 meses en un 90%. Modelos matemáticos indican que la estrategia del nido (vacunar a la madre en el posparto inmediato y a los adultos y adolescentes convivientes y cuidadores del recién nacido) reduce en un 70% la incidencia de tos ferina en niños <2meses. Se pretende realizar un ensayo en el que 340 gestantes serán vacunadas con dTpa mientras otras 340 lo serán en el posparto inmediato; a todos los convivientes y cuidadores del recién nacido se ofrecerá vacunarse con dTpa. Tras analizar las razones científicas y éticas del ensayo, se concluye que es ética y legalmente aceptable ofrecer la participación en este ensayo a gestantes que viven en comunidades donde se les ofrece vacunarlas con dTpa.

A re-emergence of pertussis has recently been observed, with most reported cases occurring in children between the ages of 1 and 2 months. In Spain, the incidence of pertussis peaked in 2011 between 600 and 700 cases/100,000 births,1 before a vaccination campaign against tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) was initiated, which was administered to children at 2, 4, and 6 months. 3281 cases were reported in Spain in 2011, of which 49% were confirmed or probable cases.1 Between 1997 and 2011, based on the Minimum Basic Data Set, the mean incidence rate for hospitalisations in children under one year of age was 115 cases/100,000 births, most (72%) in children under 2 months at a rate of 83 cases/100,000 births; during these 15 years, 37 children died, all under the age of 2 years.2 What typically happens is that the newborn's environment infects the infant. One family member is the primary case (source case of the infection) for between 27% and 88% of pertussis cases in infants.3,4

Several strategies are recommended to protect the infant, either through systematically vaccinating adolescents and adults, or through the cocooning strategy — vaccinating the mother and those in close contact with the infant, whether family members or not. Both strategies present difficulties in terms of logistics and acceptability. The cocooning strategy has been demonstrated to be effective in epidemic outbreaks,5 although one recent study — with a very small sample— did not demonstrate any benefits.6 This strategy can be applied correctly in periods between outbreaks,7,8 and is recommended in Australia, Canada, Germany, France, Switzerland and the United States.3

In 2011, the U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices (ACIP) recommended vaccinating pregnant women in the third trimester of pregnancy with the aim of protecting the infant.9 Anti-pertussis antibodies are passively transferred across the placenta from the mother to the foetus after the mother is vaccinated against tetanus, diphtheria and acellular pertussis (Tdap)10–13; these have a half-life of 6 weeks,14 a key window for protecting the as-yet unprotected infant.

Very limited data indicate that there are high antibody titres in newborns at 2 months of age, and that at 4 months the infants whose mothers were vaccinated with Tdap had antibody titres similar to infants with unvaccinated mothers.15 An observational study conducted in England showed that pertussis vaccination in pregnant women was 90% effective in infants under 2 months.16

ACIP recommends vaccinating all pregnant women in the third trimester of pregnancy, ideally between weeks 27 and 36. This should be complemented with the cocooning strategy, if possible vaccinating all those who will be in close contact with the baby who have not previously been vaccinated with Tdap, at least, 2 weeks in advance of the baby's probable birth; if a pregnant woman has not been vaccinated with Tdap, either before or during the pregnancy, it should be done immediately after giving birth.9,17 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists,18 as well as renowned experts from 5 Spanish medical societies,3 subscribe to this recommendation in all its terms.

Vaccines with tetanus toxoid (T and Td) are well tolerated in pregnant women and do not affect either the mother or the newborn.17 Fewer data are available on the Tdap vaccine, but those available do not reveal any unusual adverse reaction patterns.15,17,19

Tdap vaccination in pregnant women in SpainSeveral Autonomous Communities, including Catalonia, the Canary Islands, the Valencian Community, Extremadura and the Basque Country, have implemented Tdap vaccination in pregnant women between weeks 27 and 36 of their pregnancy, without making any mention of the cocooning strategy. The goal is to reach 50% coverage or higher.20,21 It was observed in Michigan (U.S.) that only 35% of women who were offered no-cost vaccination agreed to be vaccinated.22 In England, the vaccination programme acceptance rate in pregnant women approached 60%.16

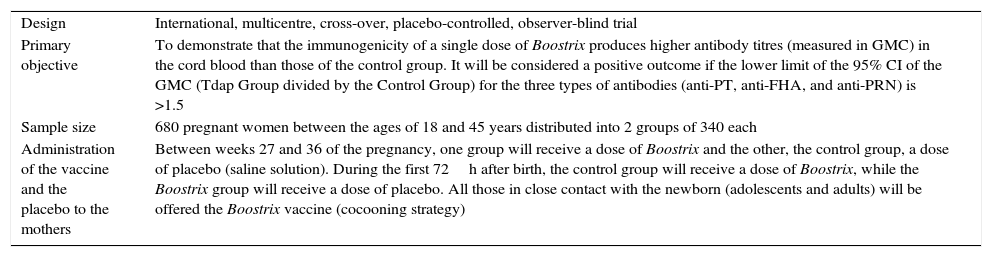

Tdap clinical trial in pregnant womenIt is proposed to conducted a clinical trial–Tdap-(Boostrix)-047–in a population which has not been previously studied. The only clinical trial conducted to date was carried out with the vaccine Adacel (from Sanofi Pasteur) in 48 women (33 received Adacel and 15 placebo) with positive, albeit preliminary, results.15 Although the composition of Triaxis (from Sanofi Pasteur MSD)–name of Adacel in Spain–differs slightly from that of Boostrix (GSK), both vaccines are marketed and present similar efficacy and safety profiles. Aside from the mentioned placebo-controlled clinical trial,15 the geometric mean concentration of only one antibody type has been determined (anti-pertussis toxin antibodies) in two observational studies with no control group,11,12 as well as the geometric mean concentration of the antibodies against three antigen components of B. pertussis contained in Boostrix in prospective observational studies with a control group in a very small number of pregnant women.10,13Table 1 summarises that main characteristics of the proposed study. It can be observed that the geometric mean concentration of antibodies against the three antigen components of B. pertussis in Boostrix will be determined in the 640 cases participating in the trial.

Main characteristics of the Tdap-(Boostrix)-047 clinical trial sponsored by GSK.

| Design | International, multicentre, cross-over, placebo-controlled, observer-blind trial |

| Primary objective | To demonstrate that the immunogenicity of a single dose of Boostrix produces higher antibody titres (measured in GMC) in the cord blood than those of the control group. It will be considered a positive outcome if the lower limit of the 95% CI of the GMC (Tdap Group divided by the Control Group) for the three types of antibodies (anti-PT, anti-FHA, and anti-PRN) is >1.5 |

| Sample size | 680 pregnant women between the ages of 18 and 45 years distributed into 2 groups of 340 each |

| Administration of the vaccine and the placebo to the mothers | Between weeks 27 and 36 of the pregnancy, one group will receive a dose of Boostrix and the other, the control group, a dose of placebo (saline solution). During the first 72h after birth, the control group will receive a dose of Boostrix, while the Boostrix group will receive a dose of placebo. All those in close contact with the newborn (adolescents and adults) will be offered the Boostrix vaccine (cocooning strategy) |

anti-FHA: anti-filamentous haemagglutinin; anti-PRN: anti-pertactin; anti-PT: anti-pertussis toxin; GMC: geometric mean concentration of antibodies; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

Some clinics and public health specialists are of the opinion that the proposed trial should not be conducted in Communities in which the healthcare authority offers no-charge Tdap vaccination to pregnant women. They argue that if pregnant women are offered the Tdap vaccine, they should not invite them to put off vaccination within the campaign in order to enrol in the trial. Is this the correct stance from an ethical perspective?

This question is posed assuming that the clinical trial has been approved by the pertinent independent ethics committee and authorised by the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices.

The situation the trial proposes is as follows:

- a)

Tdap vaccination in pregnant women is intended to protect the infant during the first 2–3 months of life. The benefit, therefore, is for the child. Unlike the ACIP recommendations, the Autonomous Communities’ vaccination programme does not include the cocooning strategy.

- b)

Healthcare authorities such as those in Catalonia and the Valencian Community have proposed vaccination coverage goals of a minimum of 50% of pregnant women in the first year of the programme, which implies that they estimate that there will be thousands who will not agree to be vaccinated while pregnant. It is highly probable that no women will be vaccinated in the days after the birth, since the Communities’ vaccination programmes do not envisage such a possibility. That the vaccine is free is far from being a determining factor in general acceptance of Tdap vaccination among pregnant women. The available data range between 35%22 and nearly 60%.16

- c)

The clinical trial intends to prove that maternal antibody transfer to the foetus in the group receiving the Tdap vaccine is superior (at a predetermined limit) to maternal antibody transfer in women who were not vaccinated while pregnant. Half of the women who agree to participate in the trial will receive the Tdap vaccine as if they agreed to be vaccinated in the vaccination campaign. The other 50% of the pregnant women in the trial will receive the Tdap vaccine within the first 72h after birth. Furthermore, everyone who will be in contact with the newborns of all the women participating in the trial will be offered the Tdap vaccine (cocooning strategy). That is, all the participating women will be vaccinated according to the ACIP recommendations, both pregnant and postpartum women.17

- d)

In Spain, pertussis incidence is highest in children between 1 and 2 months of age, and in 2011 reached 600–700 cases/100,000 births.1 More detailed and more recent (2011–2014) data available from the Valencian Community for infants up to 2 months of age indicate that the pertussis incidence rate is between 260 and 680 cases/100,000 births, between 82% and 100% of cases were admitted, equivalent to between 28 and 83 cases/year with a hospital stay of 10–12 days and with a mortality rate between 0 and 3 cases/year; the pertussis incidence rate in children between 3 and 12 months of age varied between 43 and 113 cases/100,000 population.20 The data from Catalonia–a community in which around 80% of the cases and epidemic outbreaks reported in Spain in 2011 occurred1–indicate that in that year an incidence rate of 469 cases/100,000 children under the age of one year was reached.21

- e)

The risk of children under the age of 2 months developing pertussis can be reduced by 90% if the vaccine is administered to their mothers during the third trimester of pregnancy.16 It is not known if administering a Tdap dose to those in contact with the child, in addition to the mother, would obtain an additional reduction (and by how much) in the newborn risk rate. Administering Tdap to women in the immediate post-partum period also involves a significant reduction in the risk of children <12 months developing pertussis. According to ACIP's mathematical model, this reduction in risk is equivalent to 60% of the effect of vaccinating pregnant women.17 Furthermore, other models have estimated that correctly implementing the cocooning strategy can reduce cases of pertussis in infants <3 months of age by up to 70%.23,24

With these data, the following more unfavourable theoretical scenario can be assumed regarding the risk faced by the participants in the proposed trial. The type (having pertussis) and magnitude (that it might or might not require hospitalisation) of the risk is shared by all the infants in the trial. Only the expected incidence of onset will differ in each group. Thus, the maximum incidence rate in infants younger than 2 months of age of 700/100,000, the 90% reduction of this rate if the vaccine is administered to pregnant women, and the 70% reduction if not administered to pregnant women but the cocooning strategy is correctly followed, would give incidence rates of 70/100,000 and 210/100,000, respectively; i.e. 0.7/1000 and 2.1/1000, respectively. Taking the pertussis incidence rate in infants born from vaccinated mothers as a reference (0.7/1000), 714 women would have to be vaccinated in the post-partum period (and those in close contact) for an additional case of pertussis to occur in an infant.25 Note that the trial is to enrol 340 women in the group receiving the vaccine in the immediate post-partum period.

- f)

Rid et al.26 created a method to systematically assess risks in clinical research. A scale of the magnitude of harm in 7 situations was established, from insignificant harm (e.g., a bruise) to catastrophic harm (e.g., death), in relation to risks of daily life related to playing sport and travelling in a car. Thus, for example, playing football entails a 1/10,000 risk of suffering a complete ligament tear, and travelling in a car a 1/1,000,000 risk of death.26 Acknowledging that the risk from the trial is that the infant will develop pertussis, it is concluded that the risk of all the infants whose mothers participate in the trial (between 0.7/1000 and 2.1/1000) would be equivalent to the risk of suffering harm of a moderate magnitude (e.g., a bone fracture) in daily life (sport and driving); that is around one case/1000.26

- g)

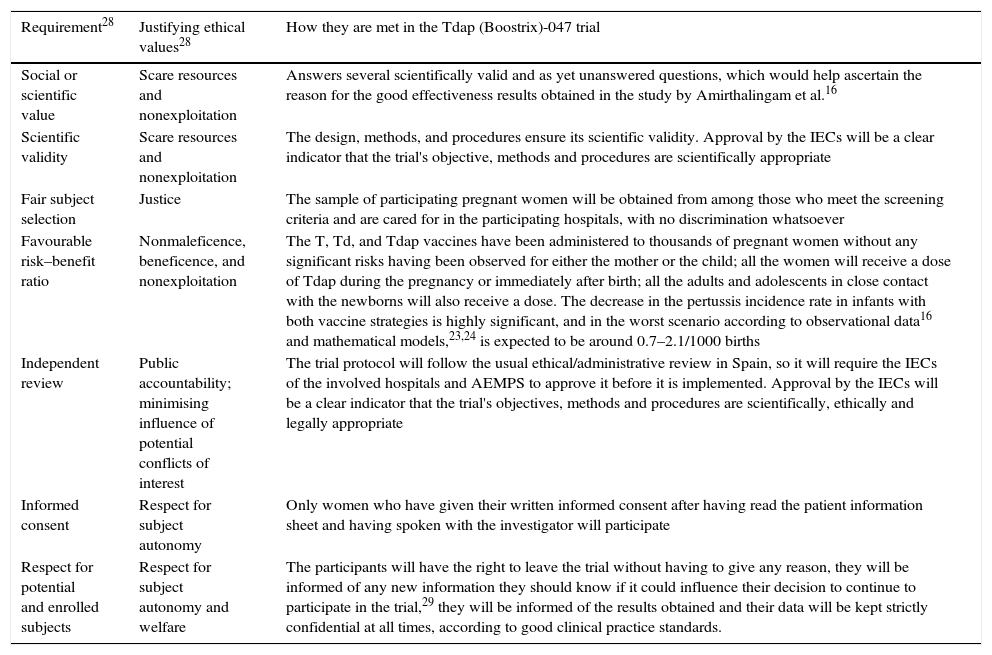

As is well known, the basic ethical principles for all research in human subjects–respect for persons, beneficence and justice–were established by the Belmont Report.27 Twenty years later, Emanuel et al.28 established the 7 ethical requirements that must be met by all research with human subjects, based on the principles in the Belmont Report, but expanded, especially in the social aspects of research. As observed in Table 2, the proposed trial meets the applicable requirements.

Table 2.Ethical requirements that must be met by all research with human subjects, according to Emanuel et al.28

Requirement28 Justifying ethical values28 How they are met in the Tdap (Boostrix)-047 trial Social or scientific value Scare resources and nonexploitation Answers several scientifically valid and as yet unanswered questions, which would help ascertain the reason for the good effectiveness results obtained in the study by Amirthalingam et al.16 Scientific validity Scare resources and nonexploitation The design, methods, and procedures ensure its scientific validity. Approval by the IECs will be a clear indicator that the trial's objective, methods and procedures are scientifically appropriate Fair subject selection Justice The sample of participating pregnant women will be obtained from among those who meet the screening criteria and are cared for in the participating hospitals, with no discrimination whatsoever Favourable risk–benefit ratio Nonmaleficence, beneficence, and nonexploitation The T, Td, and Tdap vaccines have been administered to thousands of pregnant women without any significant risks having been observed for either the mother or the child; all the women will receive a dose of Tdap during the pregnancy or immediately after birth; all the adults and adolescents in close contact with the newborns will also receive a dose. The decrease in the pertussis incidence rate in infants with both vaccine strategies is highly significant, and in the worst scenario according to observational data16 and mathematical models,23,24 is expected to be around 0.7–2.1/1000 births Independent review Public accountability; minimising influence of potential conflicts of interest The trial protocol will follow the usual ethical/administrative review in Spain, so it will require the IECs of the involved hospitals and AEMPS to approve it before it is implemented. Approval by the IECs will be a clear indicator that the trial's objectives, methods and procedures are scientifically, ethically and legally appropriate Informed consent Respect for subject autonomy Only women who have given their written informed consent after having read the patient information sheet and having spoken with the investigator will participate Respect for potential and enrolled subjects Respect for subject autonomy and welfare The participants will have the right to leave the trial without having to give any reason, they will be informed of any new information they should know if it could influence their decision to continue to participate in the trial,29 they will be informed of the results obtained and their data will be kept strictly confidential at all times, according to good clinical practice standards. AEMPS: Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices; IEC: independent ethics committee; Tdap: vaccine against tetanus, diphtheria and acellular pertussis; T: vaccine against tetanus; Td: vaccine against tetanus and adult diphtheria.

The scenario that poses the ethical problem is whether a pregnant woman who has been informed that a Tdap vaccination programme has been started in her community can be invited to participate in a clinical trial that, in itself, meets the applicable ethical (and scientific) requirements for all research in human subjects. That is, the ethical problem would not be brought up in a community in which no-cost Tdap vaccination is not offered to pregnant women.

Clinical trials posing an ethical conflict similar to the proposed trialThe scenario posed by the Tdap-(Boostrix)-047 trial is very unusual in clinical research. It did occur, however, in the exploratory trial by Munoz et al.15, which was conducted between October 2008 and May 2012. Given that ACIP has recommended Tdap vaccinations in pregnant women since June 2011,9 this means that there were pregnant women who agreed to participate in this trial after the recommendation was already in force. Aside from this case, as the beneficiary of the vaccination is the infant, there are two situations in which it can be argued that they share certain similarities with the situation of the proposed trial, in clinical research conducted in children who are not sufficiently old enough to give their assent, i.e., who are not yet 7 years old.30

The first scenario is that posed by trials in which the immunogenicity and reactogenicity of pentavalent (DTaP-HBV-IPV) or hexavalent (DTaP-HBV-IPV/Hib) vaccines administered to children at 2, 4, and 6 months of age along with a vaccine against meningococcal C conjugate with a non-toxic variant of the diphtheria toxin (MenC-CRM),31 or against meningococcal C conjugate with tetanus toxoid (MenC-TT),32 or against meningococcal C and H. influenzae (Hib-MenC).33 Since the beginning of the 21st century, the first dose of a vaccine against hepatitis B has been administered to newborns before they are discharged from hospital in several Autonomous Communities As the trial's vaccine administration schedule consisted of 3 doses at 2, 4, and 6 months, the children to be included in the study should not receive the first hepatitis B vaccine as established by the Autonomous Community vaccine schedule. To conduct the trial, the investigators had to inform the mothers about the trial immediately after giving birth and obtain their consent for their children to participate in the trial and to not receive the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine as established by the vaccine schedule. It is evident that, due to the mechanisms of transmission, the risk of a newborn becoming infecting with the hepatitis B virus is much lower than with B. pertussis, although, as has been seen, the risk of an infant in the trial developing pertussis is very low. The example is valid for the analysis since it is the mother who decides to postpone a scheduled vaccination for her child.

The second scenario is clearly different, but poses a situation that has a similar characteristic to the case at hand. They are both clinical trials in chronic diseases in which the patients are being treated with standard therapy. In these cases, if the efficacy of a new drug or a new treatment regimen is being investigated, it is common for the patients to undergo a short screening or wash out period, in which they do not receive the active medication–if anything, they can only receive rescue medication in situations of clear need–and during that period they usually receive a placebo. After this period the patients are randomised to the experimental group or to the control group (in which they will receive either active therapy or placebo). In these cases, vaccination is not postponed, but rather a medication that the patients were receiving is withdrawn for a period of weeks or even months. Thus, for example, it is common for hypertensive children between 1 and 6 years of age participating in clinical trials to have a one-week screening period with one week of placebo,34,35 which can be followed by another 14 days of placebo before receiving active medication.34 In one of the most important trials studying hypertension control in children with chronic kidney failure, one third of the participants was kept with no antihypertensive treatment for a minimum of 2 months, before being randomised to an active therapy.36 Similarly, children with mild asthma between 2 and 6 years of age participating in clinical trials usually undertake a screening period lasting between 2 and 4 weeks before being randomised to one of the treatment groups.37,38 In one such trial, one group received a placebo for 12 weeks37 or 24 weeks.38

There are, undoubtedly, multiple reasons why some parents authorise their sick children to undergo short periods of time without receiving an active treatment. Parents’ decisions about the potential participation of their children in a clinical trial are influenced by their perceptions of the well-being, low level of risk, and safety of their children in the trial, as well as the potential benefits to their children, the family and other children, if the trial has minimal impact on their routine care or offers enhanced care, and the practical aspects of their participation.39,40 Although the risk of all the above-mentioned clinical trials was minimised as much as possible, the risk perceived by the parents–and by the population in general — is usually lower if the children continue with their usual treatment than if they are included in a clinical trial. In fact, laypeople make the error of thinking that the healthcare authority only authorise new drugs that are very effective and that have no serious adverse effects,41 even though, in fact, many patients are subjected to low-value interventions.42

Doctor–patient relations and the Tdap-(Boostrix)-047 trial in Autonomous Communities that vaccinate pregnant women with TdapThe valid relationship model between physicians and patients in the West until the last decades of the 20th century was based on the physician seeking the well-being of his/her patient under the premise of a moral principle of beneficence. In this relationship, well-being is defined by the physician without giving much thought to the patient's opinion. Thus, this relationship is known as “paternalistic”.

Following the development in the Unites States of the theory of informed consent from a legal perspective,44 the rights of patients began to be forged in the United States, and later in several European countries over the last three decades of the 20th century.43 Thus, the doctor–patient relationship began to change in the 1970s: physicians started to lose the decision-making power that they had over patients and that they had enjoyed for centuries, making way for the establishment of a more equal relationship in which patients and their doctors made informed decisions by consent.43

In Spain, the General Health Act of 1986 solidified the change in the doctor–patient relationship by sanctioning the patients’ autonomy–and, as a result, the need to obtain informed consent,–against the paternalistic model of the past.45 In 1997, the Oviedo Convention, endorsed by the Council of Europe, established that all interventions may only be carried out after obtaining the free and informed consent of the person affected.46 The basic law regulating patients’ autonomy establishes that patients, after receiving the pertinent information, have the right to freely decide between the available interventions and they can even refuse to receive treatment, except in cases established by law.47 This is why all healthcare professionals must respect the decisions made freely and voluntarily by patients. Therefore, all patients have the right to be respected, and to have their decisions respected, and that their decisions be made under informed consent. This is a free and express authorisation for a certain diagnostic, preventive or therapeutic intervention to be performed, including as part of research.44

Spanish legislation, therefore, decrees that the doctor–patient relationship must be established within a framework in which the patients’ values and preferences must be taken into account by healthcare professionals and that, in case of discrepancies, the patients’ decision will prevail over that of any other consideration. This means that ethically and legally, a physician should not “decide for” their patient under any circumstances, except those provided for by law. Therefore, in the case at hand, physicians who inform pregnant women about vaccinating against pertussis with Tdap should not under any circumstances omit information about the clinical trial, since to do so would be to make a decision that does not apply to them. It should be the pregnant woman who decides, once appropriately informed, whether or not to participate in the trial or whether to be vaccinated within the programme or not be vaccinated at all.

Furthermore, physicians should not presume that the fact that the vaccination programme is ongoing means it is an insurmountable obstacle for recruiting trial subjects. It has already been seen that there are many and varied reasons why mothers or fathers authorise their very young children to participate in clinical trials. Moreover, it is interesting to observe that there is no basis for the common belief among some physicians that asking the parents of a child who could potentially participate in a clinical trial overwhelms them.39 The possibility that there are mothers who do not want to be vaccinated within the vaccination programme but who will want to participate in the trial due to its perceived benefits, should not be ruled out a priori.

ConclusionThe ultimate objective of ethics is to train people capable of making autonomous and responsible decisions.48 In light of the legal (and ethical) principle of respect for persons that establishes that it is the person who should decide–with the assistance of the healthcare professional–which diagnostic, preventive and therapeutic interventions they will undergo, it does not appear that at the present time there is space for the classic paternalistic attitude of physicians in their care activity. Therefore, in order to respect the wishes of their patients, physicians who practice in Communities that have implemented Tdap vaccination in pregnant women must inform them of the existence of the trial so that, after finding out about its risks, benefits, requirements and drawbacks, they can make a rational decision about their potential participation in the trial. Any other attitude adopted by the healthcare professionals would be paternalistic and, therefore, wrong, since it would ignore the patient's values and preferences, which should always be respected.49–51

A pregnant woman in a Community where the Tdap vaccine is offered at no cost and where the trial is being conducted has the right to know about the three choices available to her: be vaccinated within the programme, participate in the trial, or to not be vaccinated or participate in the study. This right should not be violated by a paternalistic attitude by physicians who refuse to participate in the trial–and who therefore cannot offer this possibility to their patients–understanding that it is a third-party–the healthcare authority— which, by having implemented the programme, prevents the patient de facto from making a decision–whether or not to participate in the trial–that only she should be able to make. In this scenario, the physician is in breach of their responsibility, which is no other than to appropriately inform why it is important to be vaccinated and about the possibility of participating in the trial.

FundingThis paper, carried out upon the request of GSK SA, did not require any funding.

Conflicts of interestThe author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Dal-Ré R. ¿Es éticamente aceptable invitar a una embarazada a participar en un ensayo clínico con dTpa si ello pudiera conllevar no vacunarse con dTpa antes del parto? Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:116–121.