Reflex testing is necessary to achieve the objectives of hepatitis C elimination. However, in 2017 only 31% of Spanish hospitals performed reflex test. As a consequence of that finding, reflex testing was recommended by scientific societies involved in the diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis C.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the degree of implementation of reflex testing in 2019 and to know the implementation of rapid diagnostic and/or dried blood spot testing (RDT and / or DBS) in Spanish hospitals.

MethodsCross-sectional study through a survey conducted in October 2019 to Spanish general hospitals with at least 200 beds, public or private with teaching accreditation.

Results129 (80%) hospitals responded. Reflex testing is performed by 89% of the centres vs. 31% in 2017 (P<.001). From 2017 to 2019, centres using alerts to improve continuity of care increased from 69% to 86% (P=.002). In 2019, 11% of centres can determine anti-HCV in dried spot, 15% viremia in dried spot, 0.85% anti-HCV in saliva, and 37% of antibodies and/or viremia with point of care test. 43% of hospitals have at least one diagnostic method with RDT and/or DBS.

ConclusionThe implementation of reflex testing has increased significantly, reaching 89% of hospitals in 2019. The recommendations of scientific societies could have contributed to the implementation of reflex testing. On the other hand, access to RDT and/or DBS is insufficient and initiatives are needed to improve their implementation.

El diagnóstico en un solo paso (DUSP) es necesario para conseguir los objetivos de eliminación de la hepatitis C, pero en 2017 sólo el 31% de los hospitales españoles hacía DUSP. Tras ese hallazgo, el DUSP fue recomendado por las sociedades científicas involucradas en el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la hepatitis C.

ObjetivosEvaluar el grado de implementación del DUSP en 2019, y conocer la implantación de tests de diagnóstico rápido y/o en gota seca (TDR y/o DBS) en los hospitales españoles.

MétodosEstudio transversal mediante encuesta realizada en octubre de 2019 dirigida a hospitales generales españoles con ≥200 camas, públicos, o privados con acreditación docente.

ResultadosRespondieron 129 (80%) hospitales. El DUSP lo hace el 89% de los centros vs. el 31% en 2017 (P<,001). De 2017 a 2019 los centros que utilizan alertas para mejorar la continuidad asistencial aumentaron del 69% al 86% (P=,002). En 2019, el 11% de centros puede determinar anti-VHC en gota seca, el 15% viremia en gota seca, el 0,85% anti-VHC en saliva, y el 37% de anticuerpos y/o viremia con test point of care. El 43% de los hospitales disponen al menos de un método diagnóstico con TDR y/o DBS.

ConclusionesLa implantación del DUSP ha aumentado significativamente, llegando al 89% de los hospitales en 2019. Las recomendaciones de las sociedades científicas podrían haber contribuido a la implantación del DUSP. Por otra parte, el acceso a los TDR y/o DBS es insuficiente y se necesitan medidas encaminadas a mejorar su implementación.

Hepatitis C is the main cause of liver cirrhosis and of hepatocellular carcinoma, is the most common cause of liver transplantation in Europe, causes a considerable loss of productivity, decreases patient quality of life and significantly contributes to increased healthcare expenditure.1,2 In Spain in 2018, the estimated prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies in the general adult population was 0.85%–1.1%, and the prevalence of viraemia was 0.22%−0.34%. According to the most conservative figures, in 2018, there were 337,107 people with HCV antibodies and 76,839 were viraemic. Of these, 29.4% did not know that they were infected.3,4

Since 2015, treatment with direct-acting antivirals enables a cure in most patients,5–8 meaning that it is possible to eliminate the disease. To this end, various initiatives have been proposed.9–14 One-step diagnosis (OSD) consists of making the necessary determinations for a definitive diagnosis of hepatitis C in a single sample.15–18 OSD is the most efficient form of hepatitis C screening. It is indispensable for prescribing suitable treatment early. This strategy, followed by effective reporting of results, would allow all diagnosed patients to get early access to treatment, which is, furthermore, cost-effective compared to regular clinical practice19–21 and recommended by the foremost scientific associations.22

A survey conducted in 2017 in Spain showed that, although 80% of Spanish hospitals had the resources to do OSD, it was only being done at 31% of them.23 Following that survey, a position statement recommending OSD was prepared.24 The position statement was backed by several scientific associations—the Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica [Spanish Association of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Micribiology] (SEIMC), Asociación Española para el Estudio del Hígado [Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver] (AEEH), Sociedad Española de Patología Digestiva [Spanish Association of Gastrointestinal Disease] (SEPD)—and by the Alianza para la Eliminación de las Hepatitis Víricas en España [Alliance for the Elimination of Viral Hepatitis in Spain] (AEHVE), accompanied by training and dissemination efforts. This period also witnessed the beginning of the use of new rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) and/or dried blood spot (DBS) assays utilising serum and plasma, capillary blood or crevicular fluid. These facilitate detection with no need for venipuncture, centrifugation or freezing or for qualified personnel.25,26 For these reasons, these tests are considered suitable for access to vulnerable populations such as migrants, the homeless and people in addiction treatment centres.

These factors might have contributed to altering the landscape of hepatitis C diagnosis in the past two years at Spanish hospitals. For these reasons, this study was conducted with the objective of reporting the current status of hepatitis C diagnosis, especially with regard to OSD, in Spain in 2019 and comparing it to the 2017 results. A secondary objective was to determine the state of access to new diagnostic strategies, considered essential for being able to eliminate HCV in Spanish hospitals.

MethodologyThis was an observational, cross-sectional study with data acquired through a survey aimed at hospitals in the Catálogo Nacional de Hospitales [Spanish National Catalogue of Hospitals]27 with the following inclusion criteria: 1) being a general hospital (hospitals dedicated solely to psychiatry, trauma, etc., were excluded); 2) having at least 200 beds; and 3) being a public hospital or, if private, having teaching accreditation.

The head of hepatitis C diagnosis at each selected hospital was identified by e-mail when available or via a telephone call to the hospital. Each head was sent an e-mail inviting them to participate, explaining the project and attaching the questionnaire as an Excel workbook for collecting the variables of interest: department making the diagnosis; diagnosis steps; process of reporting results; use of RDT and/or DBS diagnostic procedures; laboratory determinations performed in 2018; and opinion on OSD, tests that the hospital should have and reporting processes. The hospitals that did not reply within two weeks were sent a reminder, and up to three attempts were made to contact by telephone those that did not reply at all.

In the statistical analysis, categorical variables are reported as a percentage (%). Continuous variables with a normal distribution are reported in terms of mean and standard deviation (SD), and those without a normal distribution are expressed in terms of median and interquartile range (IQR). The associations studied were between categorical variables, and so Pearson's chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test was used. The two-tailed hypothesis test was used (〈=0.05; ®=0.2). Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package, version 20.®

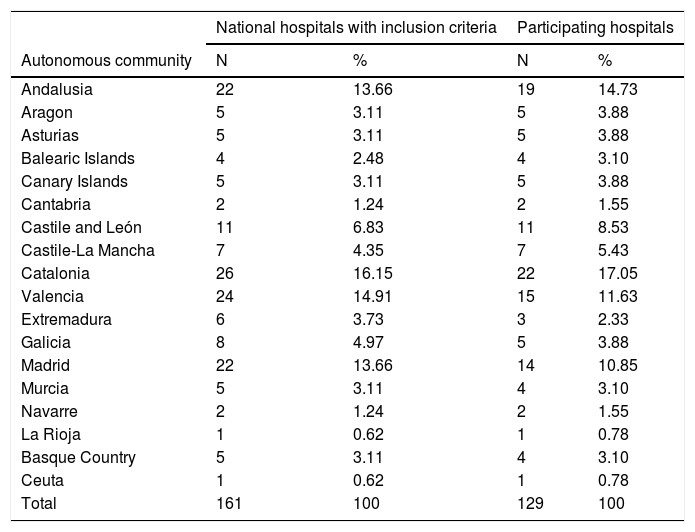

ResultsParticipating hospitalsA total of 161 hospitals met the inclusion criteria. The survey was conducted between 11 September and 26 October 2019. In total, 129 centres replied (response rate: 80.1%). The list of participating hospitals is shown in Appendix B (additional material). Table 1 shows the distribution by autonomous community (AC) of the participating hospitals. Among the 129 participating hospitals, 119 (92.2%) are publicly owned, and 127 (98.4%) have Médico Interno Residente [Medical Residency] (MIR) programmes. The hospitals have between 200 and 1500 beds (median: 469 beds; IQR: 300–800 beds).

Distribution of hospitals by autonomous community.

| National hospitals with inclusion criteria | Participating hospitals | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous community | N | % | N | % |

| Andalusia | 22 | 13.66 | 19 | 14.73 |

| Aragon | 5 | 3.11 | 5 | 3.88 |

| Asturias | 5 | 3.11 | 5 | 3.88 |

| Balearic Islands | 4 | 2.48 | 4 | 3.10 |

| Canary Islands | 5 | 3.11 | 5 | 3.88 |

| Cantabria | 2 | 1.24 | 2 | 1.55 |

| Castile and León | 11 | 6.83 | 11 | 8.53 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 7 | 4.35 | 7 | 5.43 |

| Catalonia | 26 | 16.15 | 22 | 17.05 |

| Valencia | 24 | 14.91 | 15 | 11.63 |

| Extremadura | 6 | 3.73 | 3 | 2.33 |

| Galicia | 8 | 4.97 | 5 | 3.88 |

| Madrid | 22 | 13.66 | 14 | 10.85 |

| Murcia | 5 | 3.11 | 4 | 3.10 |

| Navarre | 2 | 1.24 | 2 | 1.55 |

| La Rioja | 1 | 0.62 | 1 | 0.78 |

| Basque Country | 5 | 3.11 | 4 | 3.10 |

| Ceuta | 1 | 0.62 | 1 | 0.78 |

| Total | 161 | 100 | 129 | 100 |

N: number of hospitals.

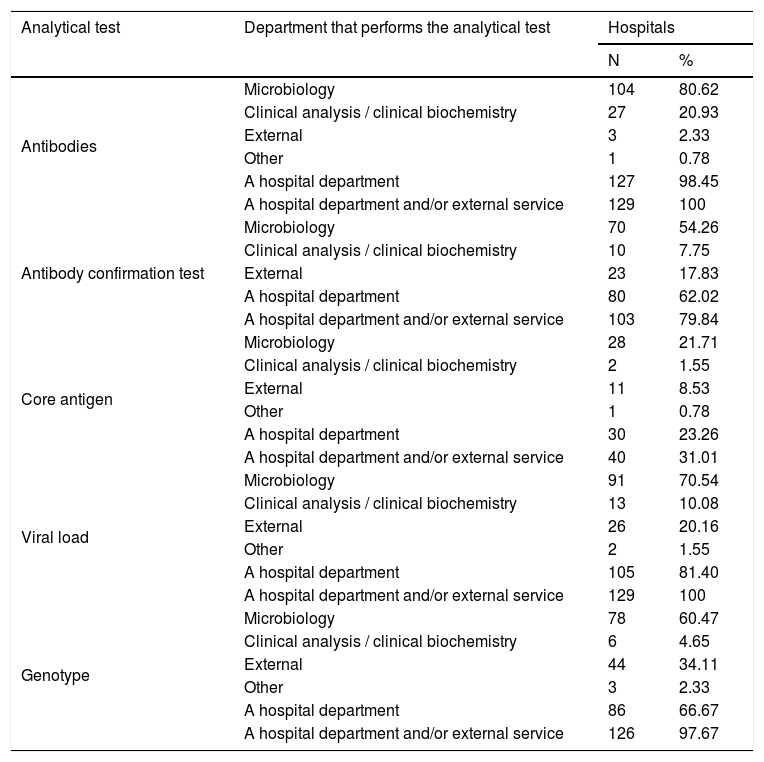

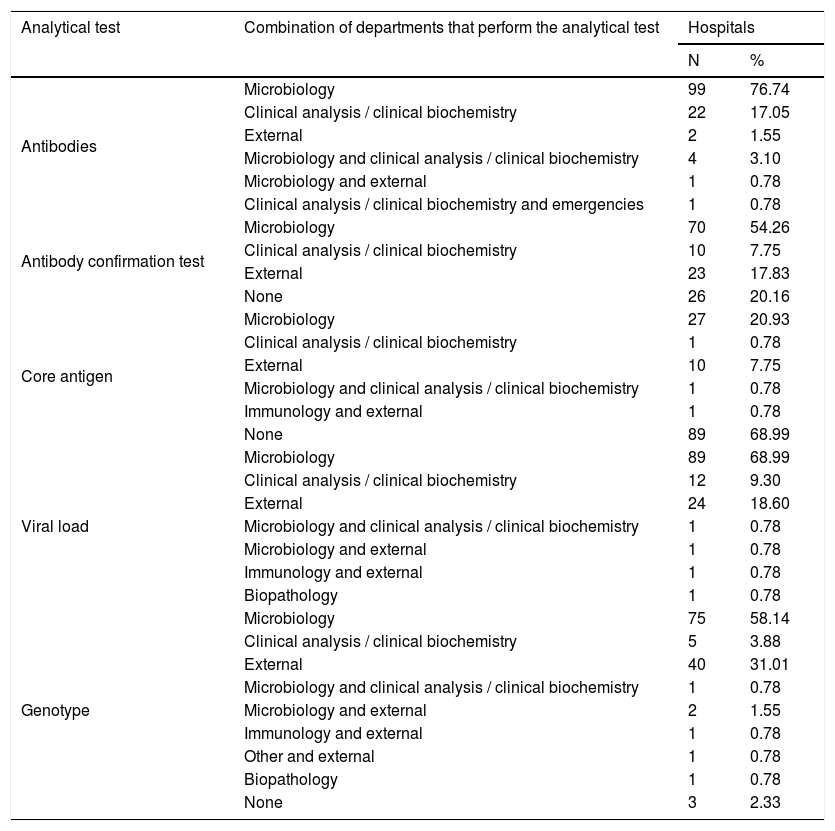

Table 2 shows the departments that perform analytical tests in HCV diagnosis, and Table 3 shows the combinations of departments that perform them.

Departments that perform analytical tests in HCV diagnosis.

| Analytical test | Department that performs the analytical test | Hospitals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | ||

| Antibodies | Microbiology | 104 | 80.62 |

| Clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 27 | 20.93 | |

| External | 3 | 2.33 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.78 | |

| A hospital department | 127 | 98.45 | |

| A hospital department and/or external service | 129 | 100 | |

| Antibody confirmation test | Microbiology | 70 | 54.26 |

| Clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 10 | 7.75 | |

| External | 23 | 17.83 | |

| A hospital department | 80 | 62.02 | |

| A hospital department and/or external service | 103 | 79.84 | |

| Core antigen | Microbiology | 28 | 21.71 |

| Clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 2 | 1.55 | |

| External | 11 | 8.53 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.78 | |

| A hospital department | 30 | 23.26 | |

| A hospital department and/or external service | 40 | 31.01 | |

| Viral load | Microbiology | 91 | 70.54 |

| Clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 13 | 10.08 | |

| External | 26 | 20.16 | |

| Other | 2 | 1.55 | |

| A hospital department | 105 | 81.40 | |

| A hospital department and/or external service | 129 | 100 | |

| Genotype | Microbiology | 78 | 60.47 |

| Clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 6 | 4.65 | |

| External | 44 | 34.11 | |

| Other | 3 | 2.33 | |

| A hospital department | 86 | 66.67 | |

| A hospital department and/or external service | 126 | 97.67 | |

N: number of hospitals.

Combinations of departments that perform analytical tests in HCV diagnosis.

| Analytical test | Combination of departments that perform the analytical test | Hospitals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | ||

| Antibodies | Microbiology | 99 | 76.74 |

| Clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 22 | 17.05 | |

| External | 2 | 1.55 | |

| Microbiology and clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 4 | 3.10 | |

| Microbiology and external | 1 | 0.78 | |

| Clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry and emergencies | 1 | 0.78 | |

| Antibody confirmation test | Microbiology | 70 | 54.26 |

| Clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 10 | 7.75 | |

| External | 23 | 17.83 | |

| None | 26 | 20.16 | |

| Core antigen | Microbiology | 27 | 20.93 |

| Clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 1 | 0.78 | |

| External | 10 | 7.75 | |

| Microbiology and clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 1 | 0.78 | |

| Immunology and external | 1 | 0.78 | |

| None | 89 | 68.99 | |

| Viral load | Microbiology | 89 | 68.99 |

| Clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 12 | 9.30 | |

| External | 24 | 18.60 | |

| Microbiology and clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 1 | 0.78 | |

| Microbiology and external | 1 | 0.78 | |

| Immunology and external | 1 | 0.78 | |

| Biopathology | 1 | 0.78 | |

| Genotype | Microbiology | 75 | 58.14 |

| Clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 5 | 3.88 | |

| External | 40 | 31.01 | |

| Microbiology and clinical analysis / clinical biochemistry | 1 | 0.78 | |

| Microbiology and external | 2 | 1.55 | |

| Immunology and external | 1 | 0.78 | |

| Other and external | 1 | 0.78 | |

| Biopathology | 1 | 0.78 | |

| None | 3 | 2.33 | |

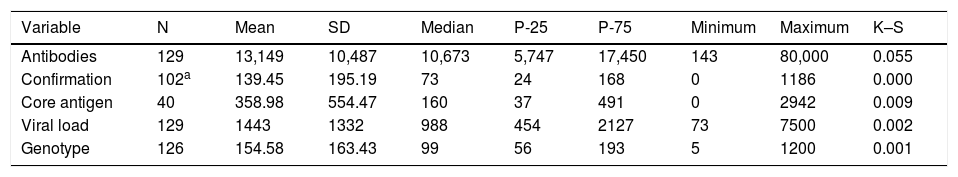

The 129 hospitals perform HCV antibody (Ab) tests in their own departments and/or via external services. Two (2.2%) centres are not able to do Ab testing and order it from external services. One centre performs it at the centre itself and also orders it from an external department. The 129 centres did a mean of 13,149 (SD: 10,487), a minimum of 143 and a maximum of 80,000 Ab tests in 2018 (Table 4).

Analytical tests performed in 2018.

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Median | P-25 | P-75 | Minimum | Maximum | K–S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | 129 | 13,149 | 10,487 | 10,673 | 5,747 | 17,450 | 143 | 80,000 | 0.055 |

| Confirmation | 102a | 139.45 | 195.19 | 73 | 24 | 168 | 0 | 1186 | 0.000 |

| Core antigen | 40 | 358.98 | 554.47 | 160 | 37 | 491 | 0 | 2942 | 0.009 |

| Viral load | 129 | 1443 | 1332 | 988 | 454 | 2127 | 73 | 7500 | 0.002 |

| Genotype | 126 | 154.58 | 163.43 | 99 | 56 | 193 | 5 | 1200 | 0.001 |

SD: standard deviation; K–S: Kolmogorov–Smirnov test; N: number of hospitals that provided test figures; P-25: 25th percentile; P-75: 75th percentile.

The Ab confirmation test is performed at 103 (79.8%) centres in their own department and/or through external services. One of the hospital departments performs it at 80 (62.0%), centres and 23 (17.8%) hospitals order it from external services. The annual number of confirmatory diagnostic tests ranged from 0 to 1186 (median: 73.0; IQR: 24–168) (Table 4).

Forty (31%) hospitals perform core antigen (Ag) tests in their own departments and/or through external services. Ninety-nine (76.7%) hospitals are not able to perform an Ag test, but 10 (7.8%) of them order one from external services. One centre performed the Ag test at the centre itself and also ordered it from an external service. The annual number of Ag tests ranged from 0 to 2942 (median: 160; IQR: 37–491) (Table 4).

Viral load (VL) tests are performed by 129 (100%) hospitals in their own departments and/or through external services. Twenty-four (18.6%) hospitals lack VL test capability, but all of them order the test from external services. Two centres that can perform the VL test on site also order it from external services. The primary care physician can order the VL test at 71 (55%) hospitals. The annual number of VL tests ranged from 73 to 7500 (median: 988; IQR: 454−2127) (Table 4).

Genotype (GT) tests are performed by 126 (97.7%) hospitals in their own departments and/or by external services. Of the forty-three 33.3%) hospitals that lack GT test capablity, 40 (31.0%) of them order it from external services. Two centres that can perform the GT test at their own centre also order it from external services. The primary care physician can order the GT test at 53 (41.1%) hospitals. The annual number of GT tests ranged from 5 to 1200 (median: 99; IQR: 56–193) (Table 4).

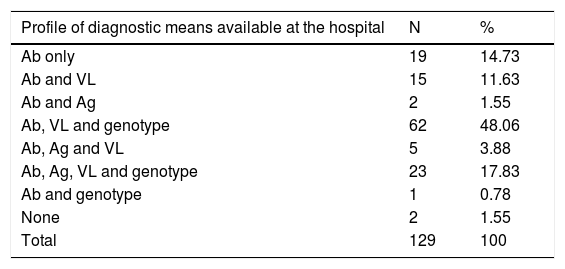

Diagnostic profiles according to available meansBased on the diagnostic tests available in the hospitals' own departments, 8 diagnostic profiles were identified, depending on what tests the hospital has available: 1) Ab only (19 hospitals; 14.7%); 2) Ab and VL (15 hospitals; 11.6%); 3) Ab and Ag (2 hospitals; 1.6%); 4) Ab, VL and GT (62 hospitals; 48.1%); 5) Ab, Ag and VL (5 hospitals; 3.9%); 6) Ab, Ag, VL and GT (23 hospitals; 17.8%); 7) Ab and GT (one hospital; 0.8%); and 8) none (2 hospitals; 1.6%) (Table 5).

Profiles of diagnostic means available.

| Profile of diagnostic means available at the hospital | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ab only | 19 | 14.73 |

| Ab and VL | 15 | 11.63 |

| Ab and Ag | 2 | 1.55 |

| Ab, VL and genotype | 62 | 48.06 |

| Ab, Ag and VL | 5 | 3.88 |

| Ab, Ag, VL and genotype | 23 | 17.83 |

| Ab and genotype | 1 | 0.78 |

| None | 2 | 1.55 |

| Total | 129 | 100 |

| Profile of total diagnostic means (available at the hospital and externally) | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Ab and VL | 2 | 1.55 |

| Ab, VL and genotype | 87 | 67.44 |

| Ab, Ag and VL | 1 | 0.78 |

| Ab, Ag, VL and genotype | 39 | 30.23 |

| Total | 129 | 100 |

Ab: antibodies; Ag: core antigen; VL: viral load; N: number of hospitals.

Taking into account the diagnostic tests that the hospital may perform in its own departments and through external services, four diagnostic profiles were identified: 1) Ab and VL; 2) Ab, VL and GT; 3) Ab, Ag and VL; and 4) Ab, Ag, VL and GT. The number of hospitals with each profile was, respectively: 2 (1.6%), 87 (67.5%), 1 (0.8%) and 39 (30.2%) (Table 5).

For a hospital to be able to perform OSD, it should have Ab and VL or Ab and Ag tests available. As a result, all hospitals are able to perform OSD with their own and/or external means, and 107 (82.9%) hospitals are able to perform it in their own departments (Table 5).

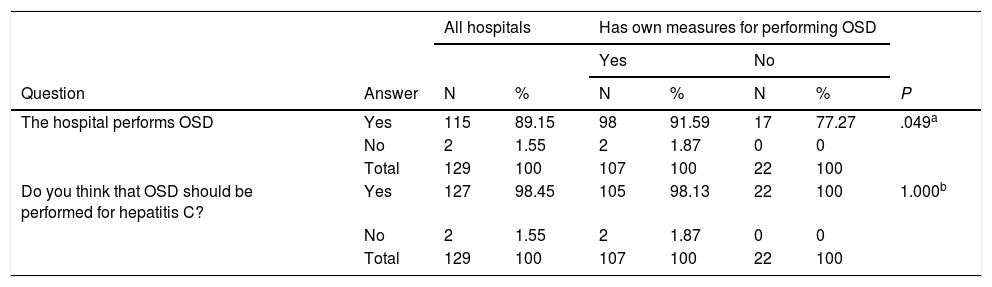

One-step diagnosisOSD can be carried out by internal departments or external services at all centres. However, in the event of an HCV-positive Ab result, OSD is performed at 115 (89.1%) hospitals. Of the 107 (82.9%) centres capable of doing OSD in their own departments, 98 do it (91.6%), whereas of the 22 hospitals that have to do it through an external service, 17 do it (77.3%) (P=.049) (Table 6).

Association between survey opinions and availability of diagnostic means at the hospital itself.

| All hospitals | Has own measures for performing OSD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||||

| Question | Answer | N | % | N | % | N | % | P |

| The hospital performs OSD | Yes | 115 | 89.15 | 98 | 91.59 | 17 | 77.27 | .049a |

| No | 2 | 1.55 | 2 | 1.87 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 129 | 100 | 107 | 100 | 22 | 100 | ||

| Do you think that OSD should be performed for hepatitis C? | Yes | 127 | 98.45 | 105 | 98.13 | 22 | 100 | 1.000b |

| No | 2 | 1.55 | 2 | 1.87 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 129 | 100 | 107 | 100 | 22 | 100 | ||

| All hospitals | The hospital performs OSD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||||

| Question | Answer | N | % | N | % | N | % | P |

| Do you think that OSD should be performed for hepatitis C? | Yes | 127 | 98.45 | 115 | 100 | 12 | 85.71 | .011b |

| No | 2 | 1.55 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 14.29 | ||

| Total | 129 | 100 | 115 | 100 | 14 | 100 | ||

| All hospitals | Can do dried blood spot Ab test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||||

| Question | Answer | N | % | N | % | N | % | P |

| Do you think that your hospital should have the DBS Ab test? | Yes | 36 | 27.91 | 11 | 78.57 | 25 | 21.74 | <.001a |

| No | 93 | 72.09 | 3 | 21.43 | 90 | 78.26 | ||

| Total | 129 | 100 | 14 | 100 | 115 | 100 | ||

| All hospitals | Can do dried blood spot VL testing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||||

| Question | Answer | N | % | N | % | N | % | P |

| Do you think that your hospital should have the DBS VL test? | Yes | 45 | 34.88 | 18 | 90 | 27 | 24.77 | <.001a |

| No | 84 | 65.12 | 2 | 10 | 82 | 75.23 | ||

| Total | 129 | 100 | 20 | 100 | 109 | 100 | ||

| All hospitals | Can do rapid diagnostic testing for Ab in saliva | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||||

| Question | Answer | N | % | N | % | N | % | P |

| Do you think that your hospital should have rapid diagnostic testing for Ab in saliva? | Yes | 22 | 17.05 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 17.19 | 1.000b |

| No | 107 | 82.95 | 1 | 100 | 106 | 82.81 | ||

| Total | 129 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 128 | 100 | ||

| All hospitals | Can do rapid VL testing with a point-of-care system | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||||

| Question | Answer | N | % | N | % | N | % | P |

| Do you think that your system should have a point-of-care (GeneXpert) system for rapid detection of VL? | Yes | 92 | 71.32 | 46 | 95.83 | 46 | 56.79 | <.001a |

| No | 37 | 28.68 | 2 | 4.17 | 35 | 43.21 | ||

| Total | 129 | 100 | 48 | 100 | 81 | 100 | ||

| All hospitals | The hospital uses at least one reporting strategy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||||

| Question | Answer | N | % | N | % | N | % | P |

| Do you think that there should be some sort of alert in the event of a diagnosis of active HCV infection? | Yes | 116 | 89.92 | 107 | 96.40 | 9 | 50 | <.001 |

| No | 13 | 10.08 | 4 | 3.60 | 9 | 50 | ||

| Total | 129 | 100 | 111 | 100 | 18 | 100 | ||

N: number of hospitals.

Statistical test used: aChi-squared; bFisher's exact test.

Of the 115 hospitals that perform OSD, 46 (40%) determine VL+GT; 44 (38.3%) determine VL only; 8 (7%) determine Ag+VL+GT; 7 (6.1%) determine Ag only; 6 (5.2%) determine Ag+VL; and 4 (3.5%) determine Ag+GT.

To the question on whether they thought that OSD should be performed, 127 (98.4%) hospitals responded yes: the 115 (100%) that are doing OSD, and 12 (85.7%) of the 14 hospitals that are not doing OSD (P=.011). The same question was answered in the affirmative by 105 (98.1%) of the 107 centres that have their own means for performing OSD and the 22 (100%) centres that do not have their own means for OSD (Table 6).

Diagnosis in more than one step: diagnostic delayOf the 14 hospitals that, in the event of a positive Ab result, do not perform OSD, 13 offered information on what they do. At 7 (53.8%) centres, they recommend a second sample, and at 6 (46.2%), they do nothing, and just wait for a second request. The lag time from a positive Ab result to VL test is a mean of 3.65 (SS: 3.34) weeks, a minimum of one week and a maximum of 12 weeks.

Rapid diagnostic test and/or dried blood spot assayAt 14 (10.9%), hospitals, Ab can be determined by DBS test; at 20 (15.5%), VL can be determined by DBS test; at one (0.8%), Ab can be determined in saliva; and at 48 (37.2%), a point-of-care test is available for rapid determination of VL. Altogether, 48 hospitals (43.4%) have at least one method of diagnosis with RDT and/or DBS, and 18 (14%) centres have more than one method for diagnosing HCV infection.

To the question "Do you think that your hospital should have the DBS Ab test available?", 36 (27.9%) hospitals answered yes, but this percentage was higher (78.6%) at the 14 hospitals able to do the DBS Ab test than at the 115 unable to do it (21.7%) (P<.001) (Table 6).

To the question "Do you think that your hospital should have the DBS VL test available?", 45 (34.9%) hospitals responded affirmatively, but this proportion was higher (90%) at the 20 hospitals able to do the DBS VL test than at the 109 that are unable to do it (24.8%) (P=.000) (Table 6).

To the question "Do you think that your hospital should have rapid diagnostic testing for Ab in saliva?", 22 (17.1%) hospitals answered yes. The one hospital that has this technique answered no, as did 106 (82.8%) of the 128 hospitals that are unable to do it (24.8%) (P=1.000) (Table 6).

To the question "Do you think that your hospital should have a point-of-care (GeneXpert) system for rapid VL detection?", 92 (71.3%) hospitals responded in the affirmative, but this percentage was higher (95.8%) among the 48 hospitals that have a point-of-care system than among the 81 with no such system (56.8%) (P=.000) (Table 6).

Strategies for reporting resultsWhen there is active HCV infection, at 111 (86.0%) hospitals, at least one reporting strategy is used (57 use more than one), whereas at 18 (14.0%) none is used. The reporting strategies used are as follows: an alert in the report at 69 (53.5%) hospitals, direct contact with the ordering physician at 51 (38.5%) hospitals, contact with the physician responsible for treatment at 44 (34.1%) hospitals, and another strategy at 19 (14.7%). Other strategies cited were: recording in the electronic record; reporting to the gastrointestinal department; reporting to the health centre; reporting to the preventive medicine specialist; monthly reports to the gastrointestinal department; or an appointment made directly with the gastrointestinal department, bypassing primary care.

To the question "Do you think that there should be some sort of alert in the event of a diagnosis of active HCV infection?", 116 (89.9%) hospitals answered yes, but this proportion was higher (96.4%) among the 111 hospitals that use at least one reporting strategy than among the 18 that do not use any (50.0%) (P=.000) (Table 6).

Comparisons to the 2017 surveyThe response rate was higher in the 2019 survey than in the 2017 survey. Out of the 161 hospitals with inclusion criteria, 129 responded (response rate 80.1%) in 2019 versus 90 out of 160 in 2017 (56.3%) (P=.000). In addition, there was a higher verified rate of adherence to OSD in 2019 than in 2017: OSD is performed at 115 out of 129 (89.1%) of the centres that responded in 2019 versus 28 out of 90 (31.1%) in 2017 (P<.001). Of the 79 centres that took part in both surveys, in 2017, 22 (27.8%) performed OSD, whereas in 2019, 70 (88.6%) did so (P=.000). Of the 57 centres that did not perform OSD in 2017, 48 (84.21%) did so in 2019. In addition, the number of respondents who thought that OSD should be performed increased from 43.3% (39/90) in 2017 to 98.4% (127/129) in 2019 (P=.000). Finally, there has also been a verified increase in the number of centres using some sort of alert system to improve healthcare continuity. This figure climbed from 68.9% in 2017 to 86.0% in 2019 (P=.002), although in 2017, 88.9% of respondents already thought that there should be some sort of alert system in the event of a diagnosis of active HCV infection, and this proportion rose to 89.9% in 2019.

DiscussionIn the study conducted in 2017, just 31% performed OSD.23 This figure increased to 89% in 2019. More notable are the findings that, of the 79 centres that took part in both surveys, 28% performed OSD in 2017 and 89% did so 2019, and that, of the 57 centres that did not perform OSD in 2017, 48 (84%) performed it in 2019. Also, in the 2017 survey, 43% of the hospitals surveyed felt that OSD should be performed, whereas that proportion was 98% in 2019.

This improvement in OSD performance may be due to numerous factors. Perhaps the most determining factor is that after the 2017 survey a position statement recommending OSD24 was prepared that was endorsed by various Spanish scientific associations (SEIMC, AEEH and SEPD) and by the AEHVE, accompanied by training and dissemination efforts. In addition, in recent years, hepatitis C has been the subject of numerous publications, leading to recommendations by scientific associations on early detection, diagnosis and treatment. Various national and international organisations have also prepared recommendations, including on its elimination.9,10,12,25,26 Finally, even society has also expressed its perception of the problem of hepatitis C and hope for a cure with current treatments.28

In addition to improvements in OSD, this study shows interesting differences compared to the study conducted in 2017. First, the response rate was higher: 80.1% in 2019 versus 56.3% in 2017. This increase may be due in part to the fact that the 2019 survey included telephone calls to non-respondents, but it may also be due to increased interest among healthcare professionals given the large presence of hepatitis C in the scientific and social spheres mentioned above.

The extent of use of the Ab confirmation test was similar to that in 2017. At present, 80% of centres perform it, whereas in 2017, 75% did it. In light of this result, it should be borne in mind that, as the sensitivity and specificity of serology are close to 100%,25,29 the performance of Ab confirmation tests does not offer improvements to diagnosis and takes away time and resources for implementing OSD. There is sufficient evidence to support the argument that the use of additional methods for HCV Ab confirmation should be stopped in clinical practice in the Spanish network of diagnostic laboratories, since it represents a barrier to suitable clinical management and healthcare continuity and poses obstacles to eradicating HCV in Spain.30

Genotyping is performed at 98% of the centres in internal departments or through external services. Genotyping is not essential for starting treatment with pangenotypic regimens and should never represent a barrier to treatment, but we believe that at centres that can have GT available in a reasonable period of time, there is no drawback to acquiring this data.

Fortunately, our study shows that, compared to 2017, unnecessary diagnostic delays have decreased. It has been reported that there is delayed diagnosis in HCV infection, and therefore in treatment,31–34 especially in vulnerable populations35,36 due to lack of healthcare continuity between Ab detection and confirmation of active infection by VL testing.37 From our study it is inferred that, as the proportion of hospitals that perform OSD decreased from 31% in 2017 to 89% in 2019, unnecessary diagnostic delays have decreased in a high proportion of hospitals. However, it would be desirable for all hospitals to perform OSD, because all have internal or external means for doing so. Implementation of OSD would improve efficiency19,20 and prevent the unnecessary outsourcing of tests that could be done at the hospital itself. Not doing OSD represents a diagnostic delay, as diagnosis at hospitals that do not perform OSD in 2019 can take anywhere from one to 12 weeks. In addition, 46% of hospitals that do not currently perform OSD do nothing and simply wait for a second request.

The strategy for reporting results is also highly variable. When there is active HCV infection, 14% of hospitals do not use any reporting strategy. This percentage was 31% in 2017. Even so, an enormous amount of variability in reporting strategies persists. The most common reporting strategies are an alert in the report, direct contact with the ordering physician and contact with the physician responsible for treatment. This variability is probably accounted for by the different characteristics of the hospitals. However, if this were to represent a delay in diagnosis, then effective reporting strategies should be developed to aid in reducing the lapse between the availability of the diagnostic result and the start of treatment. As in the 2017 survey, 90% of respondents thought that there should be some sort of alert in the event of a diagnosis of active HCV infection.

Although it was a secondary objective, this study highlights an important aspect of achieving the eradication of HCV: the use of RDT and/or DBS is marginal at the hospitals surveyed. Perhaps most importantly, the professionals surveyed thought that having this type of technology is not necessary for diagnosing this infection (just 28% of those surveyed felt that their hospital should have DBS for Ab monitoring, and 35% of those surveyed felt that their hospital should have the same for VL monitoring). One of the pillars for eradicating hepatitis C is proper diagnosis of the infection in vulnerable populations. To achieve this, it is essential to use point-of-care devices. DBS is one of the most commonly used and efficient means of doing so. This study demonstrates the important training and awareness-raising work that is still necessary among a wide range of medical groups, so that they view these new diagnostic models (RDT and/or DBS) as key tools in eradicating hepatitis C. Obtaining CE marking for one of the viraemia tests, which certifies the quality and safety of DBS polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, may be key in this regard.

One limitation of the study conducted in 2017 could be its low response rate,23 but this limitation did not affect this study, given its high response rate. In the present study, as the response rate varied by AC, some ACs may be over- or under-represented. Nevertheless, the differences in response rate are small, and the health policies of the ACs are not thought to have enough bearing on the findings of this study that their interpretation on a national level would be substantially biased.

In summary, it can be concluded that the percentage of hospitals that perform OSD increased significantly from 2017 to 89% in 2019. The measures recommended by the SEIMC, AEEH, SEPD and AEHVE, accompanied by training and dissemination efforts, might have contributed to the increased implementation of OSD. However, the new diagnostic healthcare models (RDT and/or DBS), key tools for eradicating hepatitis C in Spain, are available at less than half of hospitals, pointing to the need for measures aimed at improving said implementation.

FundingThis study was funded by the Fundación Española del Aparato Digestivo [Spanish Gastrointestinal Tract Foundation] (FEAD).

Conflicts of interestJavier Crespo: grants, advisory and speaker bureaus for Abbvie, Gilead, MSD and Janssen.

Antonio Aguilera: grants and speaker bureaus for Gilead.

Javier García-Samaniego: lectures and consultant: Abbvie, BMS, Gilead, Janssen and MSD. Grants: BMS and Gilead.

José María Eiros has done consulting work for Abbvie and Gilead.

José Luis Calleja: consultant and speaker: Gilead, Abbvie and MSD.

Federico García: grants, advisory and speaker bureaus for Roche, Hologic, Werfen, ViiV, Abbvie, Janssen, MSD and Gilead.

Antonio Javier Blasco and Pablo Lázaro received funding from the Fundación Española del Aparato Digestivo for developing the methodology for the project and drafting the manuscript.

We would like to thank the collaborating hospitals and investigators at each centre who completed the survey (Appendix B) for taking part and contributing the data that made it possible for us to conduct this study.

Please cite this article as: Crespo J, Lázaro P, Blasco AJ, Aguilera A, García-Samaniego J, Eiros JM, et al. Diagnóstico en un solo paso de la hepatitis C en 2019: una realidad en España. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:119–126.